Big Leaf Lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus)

Lupinus polyphyllus, commonly known as Big Leaf Lupine, stands as one of the most spectacular native wildflowers of the Pacific Northwest. This magnificent perennial herb creates dramatic displays with its towering spikes of blue to purple flowers rising 3-5 feet tall from robust clumps of distinctive palmate leaves. Native to moist meadows, streambanks, and forest edges from Alaska to California and inland to Montana and Idaho, Big Leaf Lupine has become a gardener’s favorite while also serving as a crucial ecological cornerstone in its native ecosystems. Its ability to fix nitrogen enriches soils, while its abundant nectar feeds countless pollinators throughout the summer months.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Lupinus polyphyllus Lindl. |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous perennial |

| Height | 3-5 feet (1-1.5 m) |

| Sun Exposure | Full sun to partial shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to high |

| Soil Type | Moist, well-drained loam |

| Soil pH | Slightly acidic to neutral (6.0-7.0) |

| Bloom Time | June to August |

| Flower Color | Blue, purple, occasionally pink or white |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3-8 |

Identification

Big Leaf Lupine is unmistakable when in bloom, with its dramatic flower spikes reaching skyward like botanical candelabras. The plant forms robust clumps from thick, woody rootstocks that can persist for decades. Individual plants typically reach 3-5 feet in height, though exceptional specimens in ideal conditions may tower up to 6 feet tall.

Leaves

The leaves are the source of the plant’s common name, with each leaf composed of 9-17 leaflets arranged in a distinctive palmate (hand-like) pattern. Individual leaflets are lance-shaped to oblanceolate, measuring 3-6 inches long and 0.5-1.5 inches wide. The leaflets radiate from a central point like fingers from a palm, creating an elegant architectural form. Leaf surfaces are typically smooth and bright green above, with fine silky hairs on the undersides that give them a slightly silvery appearance. The robust petioles (leaf stems) can reach 8-12 inches long, elevating the leaf clusters well above ground level.

Flowers

The spectacular flower spikes (racemes) are the plant’s crowning glory, rising 12-24 inches above the foliage on sturdy, unbranched stems. Each raceme contains 50-100 individual pea-like flowers arranged in a dense spiral pattern. Individual flowers measure 0.5-0.75 inches long and display the classic legume flower structure with a prominent banner petal, two wing petals, and a curved keel. While blue to purple is the most common color in wild populations, genetic variation produces flowers ranging from deep violet-blue through lavender to occasional pink or pure white forms. The flowers open progressively from bottom to top over a period of several weeks, extending the blooming season and providing sustained nectar resources for pollinators.

Seeds and Pods

Following successful pollination, Big Leaf Lupine produces distinctive flattened seed pods that mature from green to brown or black. Each pod contains 3-8 hard, glossy seeds that range in color from mottled brown to nearly black. The seeds possess a notably hard seed coat that requires scarification or stratification to germinate reliably. In nature, the pods dehisce explosively when fully dry, catapulting seeds several feet from the parent plant with an audible ‘pop’ that adds acoustic interest to late summer gardens.

Native Range

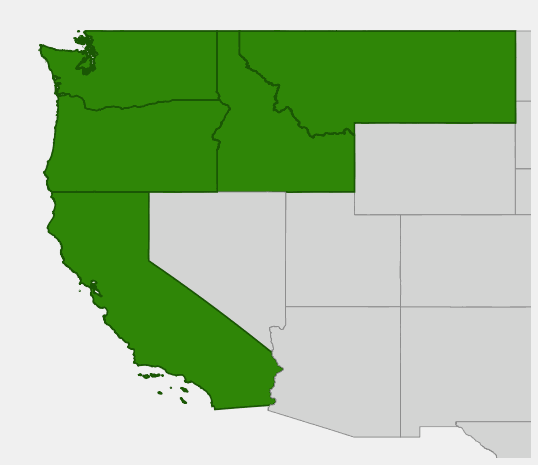

Big Leaf Lupine enjoys one of the most extensive native ranges of any western North American lupine species, reflecting its adaptability to diverse climatic conditions and elevations. The species naturally occurs from sea level coastal areas to subalpine zones at elevations reaching 9,000 feet, demonstrating remarkable ecological flexibility.

Along the Pacific Coast, Big Leaf Lupine thrives in the temperate rainforest climate from northern California through the coastal ranges of Oregon and Washington into southeastern Alaska. Here it inhabits forest openings, roadcuts, and disturbed areas where its nitrogen-fixing abilities help stabilize soils and initiate ecological succession. The coastal populations often display the most robust growth, with some plants reaching exceptional sizes in the mild, moist maritime climate.

Moving inland, the species extends through the Cascade Range and into the northern Rocky Mountains, adapting to increasingly continental climates with greater temperature extremes and reduced precipitation. In these drier environments, Big Leaf Lupine typically associates with streambanks, moist meadows, and seepage areas where summer water availability supports its substantial water requirements.

The species shows remarkable ecological breadth, occurring in plant communities ranging from coastal Sitka spruce forests to interior Douglas fir woodlands and subalpine meadow complexes. This adaptability has made it a valuable restoration species for disturbed sites throughout its range, where it serves as both a nurse plant and soil enricher for subsequent forest regeneration.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Big Leaf Lupine: Western Oregon & Western Washington

Growing & Care Guide

Big Leaf Lupine rewards gardeners with spectacular displays when provided with appropriate growing conditions. Success depends primarily on understanding the plant’s preference for cool, moist conditions and well-drained soils that mimic its native habitat preferences.

Light Requirements

While Big Leaf Lupine tolerates full sun in cooler climates, it performs best with morning sun and afternoon shade in areas with hot summers. In its native range, the species often grows in forest edges or clearings where it receives bright, filtered light for most of the day. Too much intense afternoon sun can cause leaf scorch and stress, particularly in drier conditions. In southern or inland locations, afternoon shade is essential for plant health and longevity.

Soil Preferences

Soil quality and drainage prove critical for Big Leaf Lupine success. The plant thrives in well-drained, moderately fertile soils with good organic content. Heavy clay soils should be amended with compost and coarse sand to improve drainage, as waterlogged roots are prone to rot. Conversely, sandy soils benefit from organic matter additions to improve water retention and nutrient availability. A slightly acidic to neutral pH (6.0-7.0) provides optimal growing conditions, though the plant tolerates slight alkalinity if drainage is excellent.

As a legume, Big Leaf Lupine forms symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria (Rhizobium species) housed in root nodules. This relationship allows the plant to thrive in relatively infertile soils while actually improving soil nitrogen content for neighboring plants. However, overly rich soils or excessive fertilization can inhibit nodule formation and make plants more susceptible to diseases.

Water Management

Consistent moisture proves essential, particularly during the active growing season from spring through early fall. Big Leaf Lupine naturally occurs near streams, seeps, and other reliable water sources, reflecting its substantial moisture requirements. In garden settings, deep, infrequent watering encourages robust root development, while shallow, frequent irrigation can lead to weak, disease-prone plants.

During hot summer periods, maintaining soil moisture becomes critical for plant survival and flowering performance. Mulching around plants helps conserve moisture, regulate soil temperature, and suppress competing weeds. However, avoid placing mulch directly against plant crowns, as this can encourage crown rot in humid conditions.

Planting and Establishment

Big Leaf Lupine can be established from seed or container-grown plants, each method offering distinct advantages. Seed propagation provides the most economical approach for large plantings and often produces more vigorous, well-adapted plants. However, the hard seed coat requires treatment for reliable germination. Scarification (carefully filing or nicking the seed coat) or hot water treatment (soaking in 180°F water for 24 hours) significantly improves germination rates.

Fall seeding allows natural stratification over winter, with emergence occurring in early spring. Spring seeding requires 1-3 months of cold, moist stratification in the refrigerator for optimal germination. Sow seeds 0.5 inches deep in prepared seedbeds or directly in permanent locations.

Container-grown plants establish more quickly and provide greater control over plant placement and spacing. However, lupines develop deep taproots and resent transplantation, making early spring planting essential for success. Handle root systems gently and avoid disturbing the taproot when transplanting.

Pruning and Maintenance

Big Leaf Lupine requires minimal maintenance once established. Deadheading spent flower spikes encourages additional blooming and prevents excessive self-seeding, which can become weedy in ideal conditions. Cut flower stalks back to the first set of leaves after blooms fade, leaving basal foliage intact to support root energy reserves.

In late fall or early spring, cut back dead foliage to ground level to maintain garden tidiness and reduce disease inoculum. The plant emerges vigorously from its woody rootstock each spring, often producing even more robust growth in subsequent years.

Propagation

While seed propagation remains the primary method for increasing Big Leaf Lupine, division of established clumps provides another option for gardeners. Carefully dig and divide plants in early spring before active growth begins, ensuring each division has adequate roots and growing points. However, success rates with division are lower than with seed propagation due to the plant’s taproot structure.

Self-seeding often provides the easiest method for expanding populations. Allow some spent flowers to develop mature seed pods, then collect seeds when pods begin to turn brown but before they shatter. Clean, dry seeds can be stored in cool, dry conditions for several years without significant viability loss.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Big Leaf Lupine serves as a keystone species in many Pacific Northwest ecosystems, providing essential resources for diverse wildlife communities while simultaneously improving habitat conditions for other native plants. Its ecological value extends far beyond its ornamental appeal, making it an excellent choice for wildlife-friendly gardens and restoration projects.

Pollinators

The abundant, protein-rich nectar and pollen of Big Leaf Lupine flowers attract an impressive diversity of native pollinators. Bumblebees (Bombus species) serve as the primary pollinators, with their robust bodies and buzzing flight perfectly suited for triggering the flower’s pollination mechanism. The flowers require significant force to open their tightly closed keels, making bumblebees among the few insects capable of accessing the nectar rewards inside.

Native leafcutter bees (Megachile species) and mason bees (Osmia species) also visit lupine flowers regularly, though their pollination efficiency varies with individual species and flower architecture. Carpenter bees (Xylocopa species) occasionally visit flowers but often ‘rob’ nectar by chewing holes in the flower base rather than entering through the front, providing minimal pollination benefit.

The extended blooming period, lasting 6-8 weeks or more in ideal conditions, provides sustained nectar resources during the critical summer months when many other native flowers have finished blooming. This makes Big Leaf Lupine particularly valuable for supporting pollinator populations during potential nectar shortage periods.

Specialized Butterfly Relationships

Several butterfly species have evolved specialized relationships with lupine species, including the federally endangered Karner Blue butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis). While this species primarily depends on Wild Lupine (Lupinus perennis) in its native range, the complex ecology of lupine-dependent butterflies highlights the importance of maintaining diverse native lupine populations.

Other butterflies utilize Big Leaf Lupine as both nectar source and larval host plant. The Silvery Blue (Glaucopsyche lygdamus) and several hairstreak species (Callophrys species) lay eggs on lupine foliage, with caterpillars feeding on leaves, flowers, and developing seeds. These specialized feeding relationships demonstrate the intricate ecological connections that develop over evolutionary time between native plants and their associated insect communities.

Birds and Wildlife

Big Leaf Lupine seeds provide important food resources for numerous bird species, particularly during late summer and fall when protein-rich seeds help fuel migration and winter preparation. Goldfinches, siskins, and other seed-eating birds often perch on sturdy lupine stems to access the nutritious seeds directly from ripening pods.

The dense foliage clumps offer nesting sites and protective cover for ground-nesting birds and small mammals. The plant’s robust structure remains standing through much of the winter, continuing to provide wildlife shelter and seed resources during harsh weather periods.

Large herbivores generally avoid grazing Big Leaf Lupine due to its alkaloid content, which can be toxic in large quantities. This characteristic makes lupine valuable for restoration plantings in areas with heavy deer or elk pressure, where it can establish and spread without significant browsing damage.

Ecosystem Services

As a nitrogen-fixing legume, Big Leaf Lupine significantly improves soil fertility in areas where it establishes. The root nodules containing Rhizobium bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen into forms available to other plants, essentially fertilizing the surrounding ecosystem. This process proves particularly valuable on poor soils, disturbed sites, and areas undergoing ecological restoration.

The plant’s deep taproot system helps improve soil structure and drainage while accessing nutrients from deeper soil layers. As roots decompose, they leave channels that enhance water infiltration and provide pathways for other plant roots to penetrate compacted subsoils.

Big Leaf Lupine often serves as a nurse plant in forest succession, creating improved microclimatic conditions that facilitate the establishment of tree seedlings and other native plants. The partial shade cast by lupine foliage and the improved soil conditions support a more diverse plant community than would typically establish on bare or disturbed ground.

Cultural and Historical Significance

Big Leaf Lupine holds significant cultural importance for indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest, who have utilized various parts of the plant for thousands of years. Traditional ecological knowledge recognizes lupine as both a food source and important medicinal plant, though proper preparation methods are essential due to the plant’s alkaloid content.

Some indigenous groups roasted lupine seeds after extensive processing to remove bitter alkaloids, creating a protein-rich food source. The processing methods, passed down through generations, involved repeated soaking, cooking, and leaching to make the seeds safe for consumption. Modern gardeners should not attempt to consume any part of Big Leaf Lupine without extensive traditional knowledge, as alkaloid content can vary significantly between plants and seasons.

The plant also features prominently in traditional stories and seasonal ceremonies, often representing resilience, community strength, and the arrival of summer abundance. The spectacular flower displays served as natural calendars, indicating optimal times for various seasonal activities such as fishing, hunting, and gathering other important resources.

Modern Breeding and Horticulture

Big Leaf Lupine has played a central role in the development of modern garden lupines, particularly the famous Russell Hybrids created by George Russell in Yorkshire, England during the early 20th century. Russell spent decades selecting and crossing various lupine species, using Big Leaf Lupine as a primary parent due to its robust growth habit and impressive flower spikes.

The Russell Hybrids revolutionized lupine horticulture by introducing a much broader range of flower colors, including vibrant reds, yellows, oranges, and bicolors that don’t occur in wild Big Leaf Lupine populations. These hybrids also featured denser, more compact flower spikes and improved garden performance in a wider range of climatic conditions.

Modern lupine breeding continues to build on Russell’s foundation, with contemporary cultivars offering improved disease resistance, extended blooming periods, and better heat tolerance. However, for native plant enthusiasts and wildlife gardeners, the original wild forms of Big Leaf Lupine often provide superior ecological value and better adaptation to local growing conditions.

When selecting plants for native gardens, choose seeds or plants from local or regional sources when possible. These locally adapted populations typically show better survival rates and provide optimal resources for native pollinators and other wildlife species that have co-evolved with regional plant populations.

Common Problems and Solutions

While generally robust and low-maintenance, Big Leaf Lupine can encounter several problems in garden settings. Understanding these issues and their solutions helps ensure long-term plant success.

Aphid Infestations

Lupine aphids (Macrosiphum albifrons) can occasionally build large populations on Big Leaf Lupine, particularly during cool, moist conditions in spring and early summer. These large, green insects cluster on growing tips and flower spikes, potentially reducing plant vigor and flower quality.

Natural predators including ladybugs, lacewings, and parasitic wasps usually provide effective biological control. Encouraging beneficial insect populations through diverse plantings and avoiding broad-spectrum insecticides typically maintains aphid populations at manageable levels. If intervention becomes necessary, insecticidal soap or horticultural oil applications provide effective, environmentally friendly control.

Crown and Root Rot

Poor drainage or excessive moisture around plant crowns can lead to fungal and bacterial rot problems. Symptoms include yellowing foliage, stunted growth, and eventual plant collapse. Prevention through proper site selection and soil preparation proves more effective than treatment of established infections.

Ensure excellent soil drainage and avoid overwatering, particularly during cooler months when plant growth slows. Remove affected plant material promptly and improve drainage around remaining healthy plants.

Powdery Mildew

High humidity combined with poor air circulation can promote powdery mildew infections, particularly on lower leaves. While rarely fatal, heavy infections can reduce plant attractiveness and vigor.

Provide adequate spacing between plants to promote air circulation, and avoid overhead watering that keeps foliage wet for extended periods. In severe cases, organic fungicide applications may help control established infections.

Short-lived Performance

Some gardeners find that Big Leaf Lupine plants decline after 3-4 years, leading to disappointment with the species’ longevity. However, this often reflects inappropriate growing conditions rather than inherent plant characteristics.

In suitable conditions with adequate moisture and proper soil drainage, Big Leaf Lupine can persist for decades. Ensuring optimal growing conditions and avoiding stress factors like drought, poor drainage, or excessive heat typically extends plant lifespan significantly.

Companion Planting

Big Leaf Lupine combines beautifully with numerous native and compatible plants to create stunning naturalistic gardens that support diverse wildlife populations. Successful companion plants share similar growing requirements while providing complementary colors, textures, and seasonal interest.

Native grasses such as Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis) and California oatgrass (Danthonia californica) provide elegant textural contrast to lupine’s bold foliage and flower spikes. These grasses also benefit from the nitrogen fixation provided by lupine roots, often showing improved growth and color when grown in proximity.

Other spring and summer-blooming natives that pair well include Western columbine (Aquilegia formosa), with its delicate red and yellow flowers providing color contrast, and various Penstemon species that attract similar pollinator communities. Native asters and goldenrods extend the seasonal interest into fall while providing late-season pollinator resources.

Shrub companions might include native serviceberries (Amelanchier species), Oregon grape (Mahonia aquifolium), or red-flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum), all of which provide different seasonal highlights while supporting the broader native ecosystem.