New England Aster (Aster novae-angliae)

Aster novae-angliae (syn. Symphyotrichum novae-angliae), commonly known as New England Aster, Michaelmas Daisy, or Fall Aster, stands as one of North America’s most spectacular and ecologically important autumn wildflowers. This robust perennial herb transforms landscapes across eastern and central North America each fall, painting prairies, meadows, and roadsides in brilliant shades of purple, pink, and occasionally white. Growing 3 to 6 feet tall with dozens of showy, daisy-like flowers, New England Aster provides crucial late-season nectar when most other wildflowers have finished blooming, making it an essential species for pollinators preparing for winter.

Originally classified in the massive genus Aster, this species was reclassified in the 1990s as Symphyotrichum novae-angliae based on molecular and morphological studies. However, the common names and much of the horticultural literature still refers to it by the familiar “aster” designation. Regardless of nomenclature, this plant represents the quintessential autumn wildflower — tall, stately, and absolutely covered in blooms that attract monarchs, native bees, and countless other pollinators during their critical fall migrations and preparation periods.

Beyond its obvious beauty, New England Aster plays a fundamental role in North American prairie and meadow ecosystems, serving as a keystone species that supports biodiversity throughout the growing season. Its deep taproot helps build soil structure, its summer foliage provides habitat for insects and small wildlife, and its abundant fall flowers offer one of the most reliable late-season nectar sources across its vast native range. For gardeners seeking to create authentic native landscapes that burst with color in September and October, New England Aster is an indispensable choice.

Identification

New England Aster is a tall, robust herbaceous perennial that typically reaches 3 to 6 feet in height, occasionally growing up to 8 feet in ideal conditions. The plant forms large colonies through both underground rhizomes and prolific self-seeding, creating impressive displays that can dominate entire meadows and prairie margins. Its distinctive combination of size, flower structure, and autumn blooming period makes it one of the most recognizable native wildflowers across its range.

Stems & Growth Form

The stems are sturdy, erect, and densely hairy (pubescent), giving them a somewhat rough texture. They are typically unbranched in the lower portion but become extensively branched in the upper third, creating a broad, dome-shaped flowering head. The stem hairs are particularly dense and conspicuous, helping distinguish New England Aster from some of its smoother-stemmed relatives. Multiple stems often arise from the same root system, forming large, bushy clumps that can spread several feet wide over time.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and exhibit a distinctive clasping arrangement around the stem — the leaf bases wrap partially around the stem without forming a complete sheath. Individual leaves are lance-shaped to narrowly oblong, typically 2 to 5 inches long and ½ to 1½ inches wide, with smooth margins and a rough, hairy texture on both surfaces. The upper stem leaves are progressively smaller and more numerous than the basal leaves. This clasping leaf arrangement is one of the most reliable identifying characteristics, distinguishing New England Aster from many other tall fall-blooming asters.

Flowers

The flowers are the plant’s crowning glory — numerous composite flower heads arranged in dense, flat-topped to dome-shaped clusters (corymbs) at the stem tips. Each flower head is 1 to 1½ inches across, composed of 30-50 narrow ray petals (technically ray florets) surrounding a central disc of tiny yellow tubular florets. The ray petals are most commonly deep purple to violet, but can range from light purple to pink, magenta, or rarely white. The flower heads have distinctive yellow centers that may turn reddish-brown with age.

Blooming typically occurs from late August through October, with peak flowering in September in most regions. Individual plants can produce hundreds of flower heads, creating spectacular displays that are visible from great distances. The flowers are arranged so densely that they often completely obscure the upper foliage, giving the impression of a solid mass of purple blooms.

Fruit & Seeds

The flowers develop into small, dry, one-seeded fruits called achenes, each topped with a tuft of white, silky hairs (pappus) that allows wind dispersal. The seeds mature in late fall and are released throughout autumn and early winter, often persisting on the plant well after the ray petals have fallen. Each plant can produce thousands of seeds, contributing to the species’ ability to colonize new areas and maintain large populations.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Aster novae-angliae (syn. Symphyotrichum novae-angliae) |

| Family | Asteraceae (Sunflower) |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous Perennial |

| Mature Height | 3–6 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Bloom Time | August – October |

| Flower Color | Purple to Pink |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–8 |

Native Range

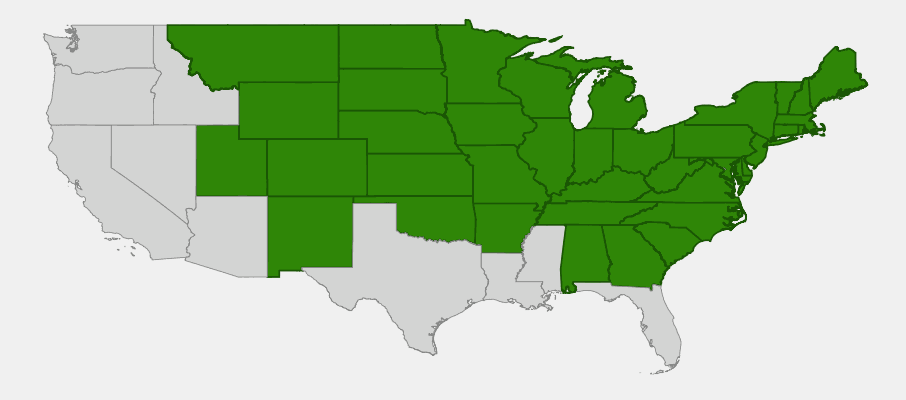

New England Aster has one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American wildflower, naturally occurring from southeastern Canada south to the Gulf of Mexico states and from the Atlantic coast west to the Rocky Mountains. This remarkable distribution spans most of the eastern two-thirds of North America, making it a truly continental species that plays important ecological roles across diverse habitats and climate zones.

The species is particularly abundant across the Great Lakes region, the upper Midwest, and the northeastern United States, where it often dominates fall landscapes in prairies, wet meadows, and open woodlands. Its range extends from Maine and the Maritime Provinces of Canada west through southern Ontario and the Prairie Provinces, then south through the central United States to eastern Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas. Scattered populations also occur in the interior western states, though it becomes less common west of the Rocky Mountains.

In its native habitats, New England Aster thrives in a variety of conditions but shows a preference for moist, fertile soils in full sun to partial shade. It commonly grows in tallgrass prairies, wet meadows, marshes, streambanks, and roadside ditches, often forming large colonies that become locally dominant during autumn blooming. The species is notably adaptable to both natural and disturbed habitats, making it valuable for restoration projects and naturalized plantings throughout its range.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring New England Aster: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

New England Aster is among the easiest and most rewarding native perennials to grow, requiring minimal care once established while providing maximum impact in the autumn garden. Its adaptability to various growing conditions, combined with its spectacular fall display and wildlife value, makes it an essential component of any native plant garden or naturalized landscape.

Light

New England Aster performs best in full sun, where it develops the most flowers and maintains a more compact, sturdy growth habit. However, it tolerates partial shade quite well, though plants in shadier conditions may grow taller and require staking to prevent lodging. In partial shade, flowering may be somewhat reduced but still spectacular. Provide at least 6 hours of direct sunlight daily for best performance.

Soil & Water

This adaptable species thrives in a wide range of soil conditions, from clay to loam to sandy soils, and tolerates pH levels from acidic to alkaline (5.0-8.0). While it performs best in consistently moist, fertile soils, established plants are quite drought-tolerant once their deep taproots are developed. The plant shows particular vigor in rich, organic soils with good moisture retention.

For optimal growth, provide regular water during the first growing season to help establishment, then water during extended dry periods. Avoid overwatering in heavy clay soils, which can lead to root rot. In naturally moist sites, such as meadows or rain gardens, New England Aster will often self-seed and naturalize beautifully.

Planting Tips

Plant New England Aster in spring after the last frost, or in early fall at least 6-8 weeks before hard frost. Space plants 2-3 feet apart to allow for their ultimate spread — mature clumps can reach 3-4 feet across. The species establishes quickly from nursery stock and typically blooms in its first year, though peak performance occurs in the second year and beyond.

When starting from seed, sow in fall for natural winter stratification, or cold stratify seeds in the refrigerator for 30 days before spring sowing. Seeds require light to germinate, so press them into the soil surface without covering. Self-seeding is common in favorable conditions, providing new plants naturally.

Pruning & Maintenance

New England Aster requires minimal pruning, but strategic cutting can improve plant performance. In early summer (June), pinch back the growing tips to encourage bushier growth and reduce ultimate height — this technique helps prevent tall plants from flopping over in wind or heavy rain. Alternatively, cut plants back by one-third in late June to achieve similar results.

After flowering, you can cut plants back to 6 inches, though many gardeners prefer to leave the seed heads for winter wildlife food and visual interest. The dried stems and seed heads provide structure in the winter landscape and food for seed-eating birds. Clean up can be delayed until late winter or early spring.

Landscape Uses

New England Aster excels in multiple garden situations:

- Prairie gardens — essential component of authentic tallgrass prairie plantings

- Autumn borders — provides spectacular late-season color when most perennials are fading

- Naturalized meadows — colonizes readily and creates impressive fall displays

- Rain gardens — tolerates wet conditions and helps with water management

- Pollinator gardens — crucial late-season nectar source for migrating butterflies and preparing bees

- Wildlife habitat — supports numerous insects and provides seeds for birds

- Erosion control — deep roots help stabilize slopes and banks

- Cut flower gardens — excellent for fall arrangements (condition stems in warm water)

Companion Plants

New England Aster pairs beautifully with other native fall bloomers such as goldenrods (Solidago species), which create stunning purple-and-yellow combinations. Other excellent companions include Big Bluestem grass, Purple Coneflower, Wild Bergamot, Joe-Pye Weed, and Ironweed. For three-season interest, combine with spring ephemerals and summer bloomers that will complement rather than compete with the aster’s autumn show.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Few native plants provide as much concentrated wildlife value as New England Aster, particularly during the critical autumn period when many animals are preparing for winter migration or dormancy. The plant serves as a vital ecological hub, supporting an remarkable diversity of species through its flowers, foliage, seeds, and structural habitat.

For Butterflies

New England Aster is absolutely essential for fall-migrating monarch butterflies, providing crucial nectar during their epic journey to overwintering sites in Mexico. The timing of peak bloom coincides perfectly with monarch migration through most of its range, often making the difference between successful migration and starvation. Beyond monarchs, the flowers attract Pearl Crescents, American Coppers, Question Marks, Painted Ladies, and various skippers and sulfurs.

Research has shown that a single large New England Aster plant in peak bloom can support dozens of butterflies simultaneously, with individual flower heads visited repeatedly throughout the day. The flowers produce abundant, high-quality nectar with excellent sugar content, making them preferred food sources over many other late-season options.

For Birds

The seeds are eagerly consumed by American Goldfinches, Pine Siskins, Common Redpolls, and various sparrow species throughout fall and winter. The dense growth form provides excellent nesting habitat for smaller songbirds, while the sturdy stems offer perching sites. During the growing season, the foliage supports numerous insects that feed insectivorous birds and their young.

The plant’s structural architecture is particularly important — the dense, branching upper portion creates microhabitats that smaller birds use for roosting and shelter during migration periods. Even after winter die-back, the remaining stems continue to provide perching spots and windbreaks.

For Native Bees

New England Aster flowers support an extraordinary diversity of native bees, including numerous species that are active only during late summer and fall. Bumblebees are frequent visitors and can be seen working the flowers from dawn to dusk during peak bloom. Sweat bees, leafcutter bees, and various solitary bees also depend heavily on the nectar and pollen, with some specialist bee species timing their lifecycle specifically to coincide with aster blooming periods.

The pollen is particularly protein-rich, helping bees build the fat reserves they need for winter survival. For social bee species, this late-season protein source is crucial for rearing the final generation of workers and reproductive individuals.

For Other Wildlife

The plant supports over 100 species of moths and butterflies as either host plant or nectar source, making it one of the most lepidoptera-diverse native plants. Many beneficial insects, including predatory beetles, parasitic wasps, and flower flies, use the dense flower clusters as hunting grounds and habitat. Small mammals occasionally browse the foliage, and deer find both the leaves and flowers palatable, though grazing pressure is typically manageable.

Ecosystem Role

New England Aster plays a keystone role in maintaining pollinator populations during the crucial autumn transition period. Its ability to form large colonies creates substantial habitat patches that support viable populations of specialized insects. The deep taproot system helps improve soil structure and access deep nutrients, while the extensive above-ground biomass contributes significant organic matter when it decomposes.

In prairie ecosystems, New England Aster helps maintain diversity by providing structural complexity and creating microhabitat variation. Its tendency to form patches rather than completely dominating an area allows other species to persist while benefiting from the pollinator activity it attracts.

Cultural & Historical Uses

New England Aster holds a significant place in North American indigenous ethnobotany, with numerous tribes utilizing the plant for medicinal, ceremonial, and practical purposes. The Ojibwe people used leaf preparations as a hunting charm, believing it would attract game animals. The Cherokee employed root decoctions to treat fever and as a poultice for skin conditions, while the Iroquois used various plant parts to treat headaches and as a general tonic.

The Potawatomi people had multiple uses for the plant, including burning the dried leaves as a smudge for spiritual purification and using the flowers in dyes to color clothing and basketry materials purple. The Menominee tribe used the entire plant in steam baths for treating various ailments, and the roots were sometimes chewed to relieve stomach problems.

Early European settlers learned many of these uses from indigenous peoples and incorporated New England Aster into their own folk medicine practices. The common name “Michaelmas Daisy” comes from the plant’s blooming period around Michaelmas (September 29), a traditional Christian festival marking the beginning of autumn. This timing made it a popular flower for fall decorations and harvest celebrations.

During the Victorian era, New England Aster became popular in ornamental gardens, leading to the development of numerous cultivars with varying flower colors and plant heights. Many of these cultivars are still grown today, though the straight species remains most valuable for wildlife habitat. The plant was also used historically as a natural dye source, producing various shades of yellow and green depending on the mordants used.

In modern times, New England Aster has become a symbol of prairie restoration and native plant gardening movements. Its spectacular autumn displays and obvious wildlife value have made it a flagship species for demonstrating the beauty and ecological importance of native plants. Many botanical gardens and nature centers use large New England Aster displays to educate visitors about native plant benefits and natural ecosystem functions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do New England Asters spread aggressively?

New England Aster spreads moderately through both underground rhizomes and self-seeding. While it forms colonies over time, it’s not typically considered aggressively invasive in home garden settings. The spread is generally manageable and can be controlled through division every 3-4 years and deadheading if you want to prevent self-seeding. Many gardeners actually welcome its spreading tendency as it creates beautiful naturalized drifts.

Why are my New England Asters falling over?

Tall New England Asters can become top-heavy and flop over, especially in rich, moist soils or partial shade conditions. Prevent this by cutting plants back by one-third in late June, which encourages bushier, more compact growth. Alternatively, pinch growing tips in early summer. Staking is another option, though many gardeners prefer the more natural look achieved through pruning.

When should I divide New England Asters?

Divide clumps every 3-4 years in early spring just as new growth emerges, or in fall after flowering. Division helps maintain plant vigor, prevents overcrowding, and provides new plants for other areas of the garden. Use a sharp spade to cut through the root mass, ensuring each division has both roots and growing points.

Are New England Asters deer resistant?

New England Asters are generally not deer resistant — deer find both the foliage and flowers quite palatable. In areas with heavy deer pressure, consider protecting young plants with fencing or deer repellent until they’re well-established. Mature plants can usually tolerate moderate browsing, though heavy deer pressure may significantly reduce flowering.

Can I grow New England Aster from seed?

Yes, New England Aster is easy to grow from seed. Seeds need a cold stratification period and light to germinate. Either sow outdoors in fall for natural winter stratification, or stratify seeds in the refrigerator for 30-60 days before spring sowing. Press seeds into the soil surface without covering. Germination typically occurs in 14-21 days under proper conditions.

What’s the difference between New England Aster and other fall asters?

New England Aster is distinguished by its clasping leaves (leaves wrap around the stem), hairy stems and leaves, and typically purple flowers with yellow centers. It’s generally taller and more robust than most other asters. Aromatic Aster has smaller flowers and smooth stems, while Heath Aster has tiny white flowers. Smooth Blue Aster has smooth leaves and stems with blue-purple flowers.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries New England Aster?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota