Alleghany Serviceberry (Amelanchier laevis)

Amelanchier laevis, commonly called Alleghany Serviceberry or Smooth Serviceberry, is one of the most beautiful and ecologically valuable small trees native to the eastern United States. A member of the rose family (Rosaceae), it lights up the early spring landscape with brilliant masses of pure white flowers — often the first tree to bloom before the forest canopy leafs out, sometimes even before the last snow has fully melted. The emerging leaves are distinctively bronze or purple-tinged, providing a stunning color contrast with the white blossoms that makes this species instantly recognizable.

Alleghany Serviceberry typically grows as a large multi-stemmed shrub or small tree, reaching up to 25 feet tall, with smooth gray bark that develops subtle striping with age. Its fruits — small, juicy, dark purple berries that ripen in June — are among the most important early-summer wildlife food sources in eastern forests, eagerly consumed by dozens of bird species and mammals. For humans, the berries are sweet and edible, tasting somewhat like blueberries with a hint of almond, and were a significant food source for Indigenous peoples throughout the region.

In the garden, Alleghany Serviceberry is a versatile, four-season performer: spectacular white spring blooms, sweet summer fruit, brilliant orange-red fall color, and attractive gray bark that provides winter interest. It thrives at the woodland edge or in naturalistic plantings and is remarkably adaptable to a range of soil types and light conditions. Its combination of wildlife value, ornamental appeal, and ease of care make it one of the finest small native trees for landscaping in the Mid-Atlantic and northeastern states.

Identification

Alleghany Serviceberry is a large shrub or small tree, usually growing 15 to 25 feet tall with a spread of 15 to 20 feet. It typically grows with multiple stems from the base, though it can be trained to a single trunk. The smooth, gray bark develops fine vertical fissures and subtle striping with age, giving it an attractive appearance year-round. One of the best ways to distinguish A. laevis from the closely related Shadblow Serviceberry (A. canadensis) is the distinctly bronze or purplish color of the young, emerging leaves, which unfurl simultaneously with the flowers in spring.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and oval to elliptical in shape, 1½ to 2½ inches long with finely toothed margins. They emerge with a distinctive bronzy-purple color in spring before gradually maturing to a medium green through summer. The leaf undersides are smooth and pale — unlike some other serviceberries that have hairy undersides. In autumn, the foliage turns exceptional shades of orange, red, and deep crimson, rivaling any cultivated flowering tree for fall color impact.

Flowers & Fruit

The flowers appear in drooping racemes of 4 to 10 blossoms, each flower with five narrow white petals about ½ inch long. They bloom in mid-March to early April — typically among the very first woody plants to flower in the eastern forest, appearing before or simultaneously with the emerging leaves. The timing is so reliable that Indigenous peoples used serviceberry bloom as a cue for spring activities and the migration of fish runs, giving rise to the common name “Shadblow” for related species (referring to the migration of shad fish).

By June, the flowers give way to small, round, pome-type fruits ¼ to ⅜ inch in diameter that ripen from green through red to deep purple-black. The fruits are sweet, juicy, and highly palatable, with a mild almond flavor from the seeds. They are eagerly consumed by birds (especially robins, catbirds, waxwings, and orioles), bears, foxes, and many other mammals — and by humans as well. The brief fruiting window (just 2–3 weeks) means competition for the fruit is intense, and birds can strip a tree bare within days of ripening.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Amelanchier laevis |

| Family | Rosaceae (Rose) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub / Small Tree |

| Mature Height | 25 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | March – April |

| Flower Color | White |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–8 |

Native Range

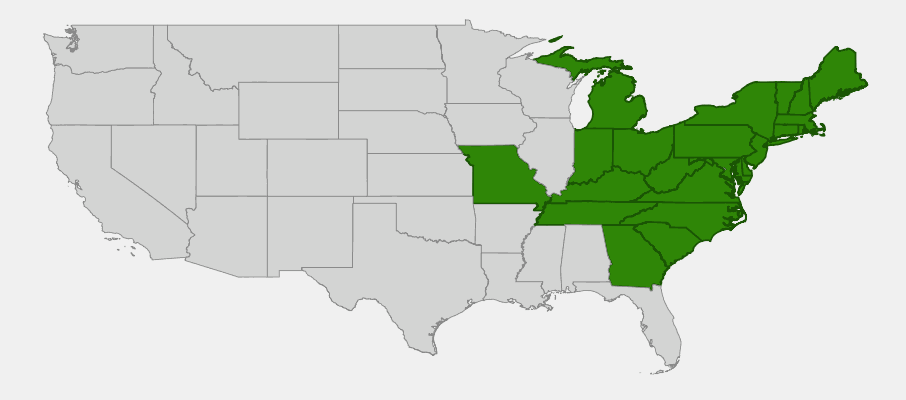

Alleghany Serviceberry is native to eastern North America, ranging from the Maritime Provinces of Canada south through New England, the Mid-Atlantic states, and into the southern Appalachian Mountains. Its range extends from Maine and New Hampshire west through New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia, and south along the Appalachians into the higher elevations of Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, and Ohio. The species is most abundant in the forest understory and at woodland edges from sea level to elevations of about 5,000 feet in the southern Appalachians.

In its natural habitat, Alleghany Serviceberry typically grows as a woodland edge species — thriving at the transition between open meadows and deciduous forest, along forest roads and streams, and in gaps in the forest canopy. It is especially common in acidic, well-drained soils on rocky slopes and ridges throughout the Appalachian region. The species grows alongside sugar maple, red oak, wild black cherry, and spicebush in mixed mesophytic forests, and with pitch pine and blueberry on more acidic, sandy soils.

The genus Amelanchier is taxonomically complex, with many overlapping species that hybridize readily in the wild. Alleghany Serviceberry is most easily distinguished from the closely related A. canadensis (Shadblow) by its smooth (rather than hairy) leaf undersides and its characteristic bronze-tinged emerging leaves. Where the two species grow together in transitional habitats, intermediate forms are common. For landscaping purposes, both species offer similar wildlife value and ornamental qualities.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Alleghany Serviceberry: New York, Pennsylvania & New Jersey

Growing & Care Guide

Alleghany Serviceberry is one of the most rewarding native shrubs/small trees for the eastern garden. It combines spectacular ornamental appeal with remarkable ease of care once established, and its wildlife value is exceptional. Understanding its natural habitat preferences will help you site and care for it successfully.

Light

Alleghany Serviceberry grows best in full sun to part shade. In full sun, it develops its densest form, most prolific flowering, and heaviest fruit set — making it the best choice for wildlife gardens where maximum berry production is desired. In part shade (3–6 hours of direct sun), it grows more loosely and open, somewhat like it does in its natural woodland edge habitat. It can survive in deeper shade but produces fewer flowers and fruits. Avoid placing it in dense, continuous shade where it will become etiolated and decline.

Soil & Water

Serviceberry is adaptable to a range of soil types, including clay, loam, and sandy soils, as long as drainage is reasonable. It prefers slightly acidic soils (pH 5.5–6.5) that are consistently moist but not waterlogged — conditions typical of its natural woodland habitat. Once established (2–3 years), it is moderately drought tolerant and requires little supplemental watering in most of its native range. Avoid extremely dry, compacted soils or sites with poor drainage. Mulching with 2–3 inches of organic material helps maintain soil moisture and mimic natural conditions.

Planting Tips

Plant serviceberry in early spring or fall for best establishment. Container-grown specimens transplant readily; bare-root plants can be planted in early spring while dormant. Choose a site with good air circulation to minimize disease pressure. Space plants 10–15 feet apart when used as a screen or naturalistic hedge; give single specimens at least 12 feet of clearance to allow for mature spread. Serviceberries are available from most native plant nurseries in the Northeast and are increasingly available at mainstream garden centers.

Pruning & Maintenance

Serviceberry requires minimal pruning. Remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter while the tree is dormant. If you prefer a more tree-like single-trunk form, gradually remove the lower branches and all but one or two main stems over several years. The species is relatively pest- and disease-resistant, though it can occasionally develop fire blight (a bacterial disease) in areas with high humidity. Removing infected branches promptly and sterilizing pruning tools between cuts will control any outbreak. Cedar-apple rust can also affect leaves in some areas, causing orange spots, but is generally not serious enough to require treatment.

Landscape Uses

Alleghany Serviceberry is remarkably versatile in the landscape:

- Four-season specimen tree — spring bloom, summer fruit, fall color, winter bark

- Woodland edge planting — thrives in the transition zone between sun and shade

- Wildlife garden anchor — superb bird and pollinator plant

- Naturalistic screening — multi-stemmed form creates attractive informal screens

- Riparian plantings — works well along stream banks and pond edges

- Rain gardens — tolerates periodic inundation

- Edible landscape — sweet, edible berries for human harvest too

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Few native trees offer as much concentrated ecological value as Alleghany Serviceberry. Its spring flowers, summer fruit, and year-round structure support a remarkable diversity of wildlife.

For Birds

The fruit of Alleghany Serviceberry is among the most important early-summer food sources for migratory and resident birds in the eastern United States. More than 35 species of birds are known to consume the berries, including American Robins, Gray Catbirds, Cedar Waxwings, Baltimore Orioles, Scarlet Tanagers, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, Eastern Bluebirds, and many thrushes and sparrows. The dense branching structure also provides excellent nesting habitat for small songbirds including Yellow Warblers and Song Sparrows. The early spring flowers attract the first insects of the season, which in turn draw migrating warblers and other insectivorous birds.

For Mammals

Black bears are enthusiastic consumers of serviceberry fruit, and the berries are also taken by foxes, raccoons, squirrels, chipmunks, and white-tailed deer. White-tailed deer browse the foliage and twigs, which can be a significant issue for young plants in high-deer-pressure areas. Protective caging is advisable until plants are well established and reach a browsing-proof height. Rabbits may gnaw bark in winter, so trunk protection is also recommended in areas with high rabbit populations.

For Pollinators

The early spring flowers of Alleghany Serviceberry are a critical food source for native bees and other pollinators that emerge in late winter and early spring before most other flowers are available. The flowers provide abundant nectar and pollen for native mining bees (Andrena species), mason bees, and early bumblebee queens. Native bees are the primary pollinators — honeybees are often not yet active when serviceberry blooms in March and April. By supporting early bee populations, serviceberry plantings help strengthen the pollinator communities that are essential for a healthy, productive garden throughout the season.

Ecosystem Role

Alleghany Serviceberry is a keystone species at the woodland edge — the transition zone that supports the highest biodiversity of any habitat type in eastern North America. It provides essential structure (nesting sites, perches), food (fruit, flowers, insects), and cover for dozens of species. Its early fruiting — before most other plants produce berries — makes it especially valuable as a “gap filler” in the seasonal food supply. By planting serviceberry, you anchor a complex ecological community that extends far beyond the tree itself.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Alleghany Serviceberry has a rich history of human use across eastern North America. Indigenous peoples of many nations — including the Iroquois, Lenape, Cherokee, and numerous Algonquian-speaking peoples — harvested the fruit extensively. The berries were eaten fresh, dried for winter storage, and mixed with dried meat to make pemmican — a high-energy trail food that sustained people through long winters and difficult journeys. The Iroquois also used serviceberry bark medicinally, preparing decoctions to treat ailments ranging from venereal diseases to excessive menstrual bleeding.

The common name “serviceberry” has a charming origin story: the trees bloom at roughly the same time that mountain passes in Appalachia became clear enough in spring for traveling preachers to hold funeral services that had been postponed all winter — hence “serviceberry” for the time of services. Another explanation ties the name to the resemblance of the fruit to “sarvisberries” (Sorbus, the mountain ash), though the serviceberry is not related. Early European settlers quickly adopted the fruit for pies, jams, and preserves, and serviceberry pie was a common spring treat in frontier communities throughout the East.

The light, hard, fine-grained wood of serviceberry was used by Indigenous peoples for arrow shafts, tool handles, and walking sticks. The straight, dense wood takes a high polish and was valued for its strength and resilience. Early settlers used it for tool handles, fishing rods, and fence posts. Today, the primary use of serviceberry is ornamental and ecological — it is one of the most widely planted native trees in Mid-Atlantic and northeastern landscapes, celebrated for its multi-season interest and exceptional wildlife value.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are serviceberries edible for humans?

Yes — Alleghany Serviceberry produces sweet, edible berries that taste similar to blueberries with a hint of almond. They can be eaten fresh, made into jams, pies, and muffins, or dried for use in trail mix. The main challenge is competing with birds, who can strip a tree bare within days of the fruit ripening in June.

How do I tell Alleghany Serviceberry apart from other serviceberries?

The key identifying feature of Amelanchier laevis is the bronze or purplish color of the young leaves as they emerge simultaneously with the white flowers in spring. The leaf undersides are also smooth (glabrous), unlike some related species that have hairy undersides. The long, drooping flower clusters (racemes) are another distinctive feature.

Does serviceberry need a pollinator partner?

Alleghany Serviceberry is largely self-fertile, so a single plant will produce fruit. However, planting two or more specimens (or having other serviceberry species nearby) typically results in better fruit set and larger crops — beneficial both for wildlife and for human harvest.

How fast does Alleghany Serviceberry grow?

Serviceberry has a moderate growth rate of about 1–2 feet per year under good conditions. Young plants establish relatively quickly and typically begin flowering within 2–3 years of planting. The species is long-lived and will continue to increase in size and wildlife value for decades.

Is serviceberry deer resistant?

No — white-tailed deer readily browse serviceberry foliage and twigs, and can severely damage or kill young plants. Protect new plantings with wire caging or deer fencing until they reach a height of at least 5–6 feet. Once established and beyond easy browsing height, deer pressure becomes much more manageable.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Alleghany Serviceberry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: New York · Pennsylvania