American Hazelnut (Corylus americana)

Corylus americana, commonly known as American Hazelnut or American Filbert, is a magnificent native deciduous shrub that has provided both sustenance and ecological value across eastern North America for millennia. This member of the Betulaceae (birch) family forms dense, spreading colonies through underground suckers, creating valuable wildlife thickets while producing some of the finest native nuts in North America. The common name “hazelnut” derives from the Old English “hæsel,” reflecting the deep cultural connection Europeans maintained with their own native hazelnuts — a connection that Indigenous peoples had already established with this American species thousands of years earlier.

Growing naturally in woodland edges, thickets, and partially shaded areas from southern Maine to Georgia and west to Saskatchewan and Oklahoma, American Hazelnut typically reaches 6 to 12 feet in height, forming multi-stemmed colonies that can spread 8 to 15 feet wide. Its large, heart-shaped leaves with prominent veining turn brilliant yellow-orange in fall, while the distinctive male catkins dangle conspicuously in early spring before the leaves emerge. The edible nuts, enclosed in attractive papery husks, have sustained both wildlife and human communities for generations — and continue to be prized today for their rich, buttery flavor that rivals any commercial hazelnut.

What makes American Hazelnut particularly remarkable is its exceptional ecological value combined with practical usefulness. While many native shrubs excel at either wildlife support or human utility, American Hazelnut delivers both abundantly. Its dense branching structure provides crucial nesting sites and thermal cover for birds, the nuts feed dozens of wildlife species, and the early flowers support native pollinators when few other food sources are available. For the gardener, it offers delicious homegrown nuts, striking fall color, early spring interest, and the satisfaction of growing a plant that truly belongs in the North American landscape.

Identification

American Hazelnut grows as a large, multi-stemmed deciduous shrub typically reaching 6 to 12 feet tall and spreading 8 to 15 feet wide through underground suckers. In ideal conditions, it can occasionally reach up to 15 feet in height. The overall growth form is that of a dense, rounded shrub with multiple stems arising from the ground, creating an excellent wildlife thicket. Young stems are brown and slightly hairy, while older wood develops a smooth, gray-brown bark.

Stems & Bark

The young twigs are brown to reddish-brown with fine pubescence (soft hairs), becoming smooth and gray-brown with age. The bark is thin and smooth on younger stems, developing shallow fissures and a slightly scaly texture on older, thicker stems. Unlike many shrubs, American Hazelnut rarely develops a single dominant trunk, instead maintaining its characteristic multi-stemmed form throughout its life. The wood is moderately hard and has been used historically for tool handles, fishing poles, and small construction projects.

Leaves

The leaves are among American Hazelnut’s most distinctive features — they are broadly oval to heart-shaped, 3 to 5 inches long and 2½ to 4 inches wide, with a pointed tip and rounded to slightly heart-shaped base. The leaf margins have prominent double teeth (doubly serrate), and the surface shows conspicuous parallel veins running from the midrib to the leaf edge. The upper surface is dark green and somewhat rough to the touch, while the underside is paler and softly hairy. In autumn, the foliage transforms into brilliant shades of yellow, orange, and occasionally red before dropping.

Flowers

American Hazelnut is monoecious, producing both male and female flowers on the same plant. The male flowers form pendulous catkins 2 to 4 inches long that dangle conspicuously from the branches in early spring, often before the leaves emerge. These yellowish catkins are among the first signs of spring in many woodlands, releasing clouds of pollen when disturbed. The female flowers are much smaller and less obvious — tiny red tufts that emerge from buds on the same branches, typically appearing slightly later than the male catkins.

Fruit & Nuts

The nuts are the plant’s crowning glory — they mature in late summer to early fall, enclosed in distinctive papery, leafy husks (bracts) that are deeply lobed and extend well beyond the nut itself. Each nut is roughly ½ inch in diameter, brown when ripe, and contains a delicious kernel with a rich, buttery flavor. The nuts typically occur in clusters of 2 to 6, though individual shrubs vary considerably in their productivity. The husks initially appear green and tightly closed, gradually turning brown and opening to reveal the ripe nuts within.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Corylus americana |

| Family | Betulaceae (Birch) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 6–12 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to Low (Drought Tolerant) |

| Bloom Time | March – April |

| Flower Color | Yellow (male catkins) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

Native Range

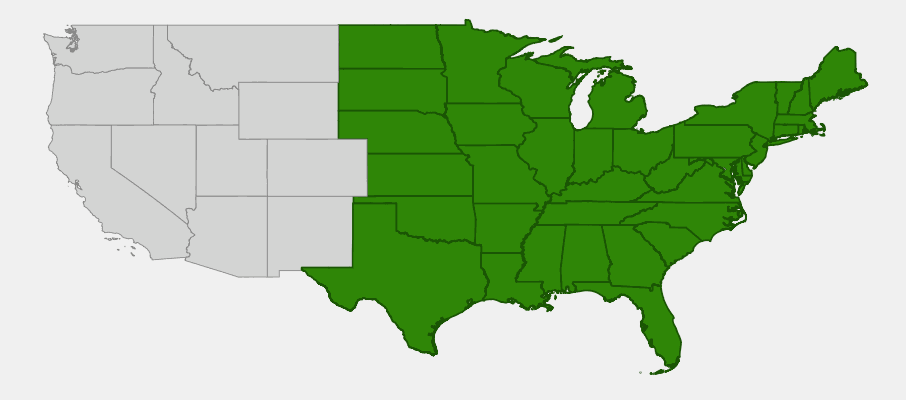

American Hazelnut has one of the broadest native ranges of any North American shrub, stretching from southern Maine and southern Quebec south to northern Florida and northern Georgia, and west to Saskatchewan, eastern Montana, eastern Wyoming, eastern Colorado, Oklahoma, and eastern Texas. This impressive range encompasses virtually the entire eastern half of North America, from boreal forests in the north to pine woodlands in the south, and from Atlantic coastal plains to Great Plains edges in the west.

Throughout this vast range, American Hazelnut typically grows in woodland edges, forest openings, thickets, stream banks, and prairie borders — essentially anywhere that provides partial shade and protection from the harshest sun and wind. It thrives in the transitional zones between forest and grassland, often forming dense colonies along fence rows, abandoned fields, and woodland margins. The species shows remarkable adaptability to different soil types and moisture conditions, though it generally prefers well-drained soils with at least some organic matter.

Ecologically, American Hazelnut serves as an important component of edge habitats throughout its range. These edge environments — where forest meets grassland, or where woodlands transition to more open areas — support exceptionally high biodiversity, and American Hazelnut’s dense, spreading growth form creates the structural complexity that many species depend upon. The shrub’s ability to spread through underground suckers allows it to quickly colonize disturbed areas and create stable wildlife habitat.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring American Hazelnut: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

American Hazelnut is among the most rewarding native shrubs to grow, combining ornamental beauty, wildlife value, and nut production in a single, relatively low-maintenance plant. Success lies in understanding its natural growth habits and providing conditions that approximate its native woodland edge habitat.

Light

While American Hazelnut tolerates a range of light conditions, it performs best in partial shade — ideally morning sun with afternoon shade, or dappled sunlight throughout the day. In too much shade, flowering and nut production decrease significantly, while in full sun, the plant may struggle during hot summers and require more consistent watering. The ideal site mimics a woodland edge where the shrub receives bright light but is protected from the harshest midday sun.

Soil & Water

American Hazelnut is remarkably adaptable to different soil types, growing well in everything from sandy loam to clay, though it prefers well-drained soils with good organic matter content. The ideal pH range is 6.0 to 7.5 (slightly acidic to slightly alkaline). Once established, the plant is quite drought tolerant, but consistent moisture during the growing season improves both growth and nut production. Avoid waterlogged soils, as the roots may rot in constantly wet conditions.

Planting Tips

Plant American Hazelnut in fall or early spring while dormant. Space individual plants 8 to 12 feet apart if creating a hedge or screen, or allow for the natural colony formation by providing adequate space (15+ feet) around isolated specimens. The shrub transplants well from nursery stock, but wild plants can be difficult to move due to their extensive root systems and suckering habit. Mulch around new plantings with 2-3 inches of organic material to conserve moisture and suppress weeds.

Pruning & Maintenance

American Hazelnut requires minimal pruning beyond occasional removal of dead, damaged, or crossing branches. If you wish to maintain it as a more compact shrub rather than allowing natural colony formation, remove unwanted suckers at ground level in late winter. For nut production, thin out some of the oldest stems every few years to encourage vigorous new growth, as younger wood produces more flowers and nuts. The best time for any major pruning is late winter while the plant is fully dormant.

Landscape Uses

The versatility of American Hazelnut makes it valuable in numerous landscape situations:

- Edible landscaping — excellent for food forests and permaculture designs

- Wildlife gardens — provides food, nesting sites, and cover for numerous species

- Natural hedgerow or screen — forms dense barriers when planted in groups

- Woodland gardens — perfect for naturalized forest-edge plantings

- Erosion control — the spreading root system stabilizes soil on slopes

- Restoration projects — helps establish diverse native plant communities

- Privacy screening — provides year-round structure and seasonal privacy

Wildlife & Ecological Value

American Hazelnut ranks among the most ecologically valuable shrubs in eastern North America, supporting an extraordinary diversity of wildlife species throughout the year. Its combination of early flowers, dense structure, and nutritious nuts makes it a keystone species in many woodland edge communities.

For Birds

Over 40 species of birds depend on American Hazelnut for food, shelter, or nesting sites. Ruffed Grouse, Wild Turkeys, Blue Jays, Woodpeckers, and Nuthatches consume the nuts, often caching them for winter food supplies. The dense, thorny structure provides excellent nesting sites for Gray Catbirds, Brown Thrashers, Northern Cardinals, and American Goldfinches. During migration, warblers and other insectivores find abundant insects among the foliage, while the winter structure offers crucial thermal protection during harsh weather.

For Mammals

Squirrels, chipmunks, and mice are perhaps the most obvious consumers of hazelnut nuts, but larger mammals also benefit significantly. Black Bears eat both the nuts and young shoots, White-tailed Deer browse the foliage (though mature plants are relatively deer-resistant), and Cottontail Rabbits use the dense cover for shelter. The early pollen provides food for bats that feed on insects attracted to the catkins, while the overall structure creates travel corridors and hiding places for numerous small mammals.

For Pollinators

The early spring catkins are wind-pollinated, but they provide crucial food for early-emerging native bees, flies, and other beneficial insects that feed on pollen. The female flowers, while tiny, do attract small beneficial insects. More importantly, the dense foliage throughout the growing season supports numerous caterpillars and other insects that adult pollinators need to feed their larvae — making American Hazelnut an important indirect supporter of pollinator populations.

Ecosystem Role

American Hazelnut plays a critical role in creating and maintaining the edge habitats that support biodiversity. Its ability to spread through suckers allows it to quickly colonize disturbed areas, stabilize soil, and create the structural foundation for complex plant communities. The nuts it produces are among the highest-energy foods available to wildlife, helping many species build fat reserves for winter or migration. Additionally, the shrub’s nitrogen-fixing capabilities (through association with mycorrhizal fungi) help improve soil quality for neighboring plants.

Cultural & Historical Uses

American Hazelnut has been a cornerstone species for human communities across eastern North America for thousands of years. Archaeological evidence from numerous sites — including Poverty Point in Louisiana and various Archaic period sites throughout the Midwest — demonstrates that Indigenous peoples not only harvested hazelnuts extensively but also actively managed hazelnut groves through controlled burning and selective harvesting to maintain productive stands.

Many Indigenous nations, including the Ojibwe, Cherokee, Iroquois, and numerous Plains tribes, developed sophisticated techniques for harvesting, processing, and storing hazelnuts. The nuts were typically gathered in late summer, dried thoroughly, and stored in bark containers or underground caches for winter consumption. They were often ground into meal, mixed with other foods to create pemmican-like preparations, or pressed to extract oil for both culinary and medicinal uses. The Ojibwe word for hazelnut, “bagaan,” gave its name to numerous locations throughout the Great Lakes region.

Beyond the nuts themselves, Indigenous peoples found numerous uses for other parts of the plant. The flexible young stems were woven into baskets and fish traps, while the inner bark provided materials for cordage and textiles. The wood, though not particularly durable, was used for tool handles, drumsticks, and fishing poles. Medicinally, various preparations were used to treat everything from heart problems to wounds, though modern applications are not well-studied scientifically.

European settlers quickly recognized the value of American hazelnuts, both for food and for the familiar taste that reminded them of their native European hazelnuts (Corylus avellana). During the 19th and early 20th centuries, commercial hazelnut operations existed throughout much of the Midwest, though they eventually declined due to disease pressure and competition from larger-scale operations in Oregon. Today, there is renewed interest in American hazelnuts both for commercial production and for restoration of native ecosystems, with plant breeders developing improved cultivars that combine the hardiness and disease resistance of the native species with larger nut size.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take for American Hazelnut to produce nuts?

Plants grown from seed typically begin producing nuts in 3 to 5 years, while nursery-grown plants may produce nuts in their first or second year after planting. Peak production occurs when plants are 8 to 15 years old. Cross-pollination between different plants significantly improves nut production, so plant at least two specimens if possible.

Are American Hazelnuts self-pollinating?

While American Hazelnuts are technically self-fertile (having both male and female flowers on the same plant), they produce significantly more nuts when cross-pollinated with other American Hazelnut plants. For best nut production, plant at least two genetically different plants within about 50 feet of each other.

How do I control the spreading habit if I want just one shrub?

American Hazelnuts spread naturally through underground suckers. To control this, install root barriers around the planting area, or simply mow or cut unwanted suckers at ground level each year in late winter. Regular removal of suckers will not harm the parent plant and can actually encourage more vigorous growth in the remaining stems.

When and how should I harvest the nuts?

Hazelnuts are ready to harvest when the husks begin to turn brown and open, typically in late August to early September depending on your location. The nuts should fall easily from the husks when ready. Harvest quickly, as squirrels and other wildlife are equally interested in the crop! Dry the nuts thoroughly before storing.

Do American Hazelnuts have any serious pest or disease problems?

American Hazelnuts are generally quite healthy and resistant to most serious diseases, though they can occasionally be affected by bacterial blight, canker, or fungal issues in very wet conditions. The most common “pest” is wildlife competition for the nuts! Eastern Filbert Blight, which devastates European hazelnuts, affects American hazelnuts much less severely and rarely causes significant damage.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries American Hazelnut?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota