Cattail (Typha latifolia)

Typha latifolia, universally known as Cattail, Common Cattail, or Broadleaf Cattail, stands as one of North America’s most recognizable and ecologically significant wetland plants. This robust member of the Typhaceae family has become an iconic symbol of marshes, ponds, and wetlands across the continent, instantly recognizable by its distinctive chocolate-brown, hot-dog-shaped flower spikes that crown tall stands of sword-like leaves. The common name “cattail” likely derives from the resemblance of the brown flower spike to a cat’s tail, though it has also been called bulrush, reed mace, and punks in various regions.

Growing 3 to 10 feet tall in dense, spreading colonies, Cattail is a true ecosystem engineer — a species that literally creates and modifies habitat for countless other organisms. Through its aggressive rhizomatous growth, it forms extensive stands that provide crucial wildlife habitat, prevent erosion, filter water, and create the foundation for complex wetland communities. Each plant produces the unmistakable brown flower spike in summer, followed by fluffy seed heads that disperse thousands of tiny seeds on the wind, while the tall, linear leaves persist throughout the growing season and often well into winter.

What makes Cattail particularly remarkable is its incredible versatility and ecological importance. Historically, Indigenous peoples used virtually every part of the plant for food, medicine, tools, and shelter materials, earning it the nickname “supermarket of the swamp.” Today, it continues to serve vital ecological functions as a water purifier, wildlife sanctuary, and erosion controller, while also finding modern applications in constructed wetlands, bioremediation projects, and sustainable landscaping. For gardeners with water features, rain gardens, or naturally wet areas, Cattail offers unparalleled ecological value combined with distinctive architectural presence that few plants can match.

Identification

Cattail is unmistakable once familiar, growing as a robust, colony-forming perennial that can reach 3 to 10 feet in height depending on water depth and growing conditions. The plant spreads extensively through thick, horizontal underground rhizomes, often forming dense, pure stands that can cover acres of suitable wetland habitat. Individual shoots emerge from the rhizomes in spring, quickly developing into the characteristic tall, upright growth form.

Leaves

The leaves are perhaps the most distinctive vegetative feature — they are flat, sword-like, and remarkably wide for a monocot, measuring ½ to 1 inch across and up to 9 feet long. The leaves are blue-green to dark green, with a smooth, waxy surface that helps shed water, and they emerge in a fan-like arrangement from the base of the plant. Each leaf has parallel veining typical of monocots and a slightly spongy texture due to internal air spaces (aerenchyma) that help the plant transport oxygen to submerged roots. In winter, the leaves often persist as tan or brown structures that provide continued habitat value.

Stems

The flowering stems are thick, sturdy, and completely without branches, rising 6 to 10 feet tall from the center of the leaf cluster. Like the leaves, the stems contain extensive aerenchyma tissue that appears as a spongy, honeycomb-like structure when cut in cross-section. This specialized tissue allows the plant to transport oxygen from the above-water portions to the submerged rhizomes and roots — a crucial adaptation for life in waterlogged soils.

Flowers

The flowers are arranged in the iconic cylindrical spike that makes Cattail instantly recognizable. Each spike actually consists of two parts: a lower, brown, sausage-shaped section containing thousands of tiny female flowers, and an upper, narrower section (often deciduous) containing the male flowers. The brown “hot dog” portion is typically 4 to 8 inches long and about 1 inch in diameter, densely packed with tiny flowers. The male flowers above release pollen in early summer, then typically fall off, leaving the persistent brown female spike that becomes the familiar seed head.

Seeds

The seeds develop within the brown female spike, each tiny seed attached to fine, fluffy hairs that aid in wind dispersal. When mature, the brown spike breaks apart into a mass of cotton-like fluff, releasing thousands of tiny seeds that can travel considerable distances on the wind. This stage often occurs in late fall or winter, creating spectacular displays of white fluff that can cover large areas around cattail stands.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Typha latifolia |

| Family | Typhaceae (Cattail) |

| Plant Type | Perennial Wetland Herb |

| Mature Height | 3–10 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | High (Wet) |

| Bloom Time | June – August |

| Flower Color | Brown (female spike) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–11 |

Native Range

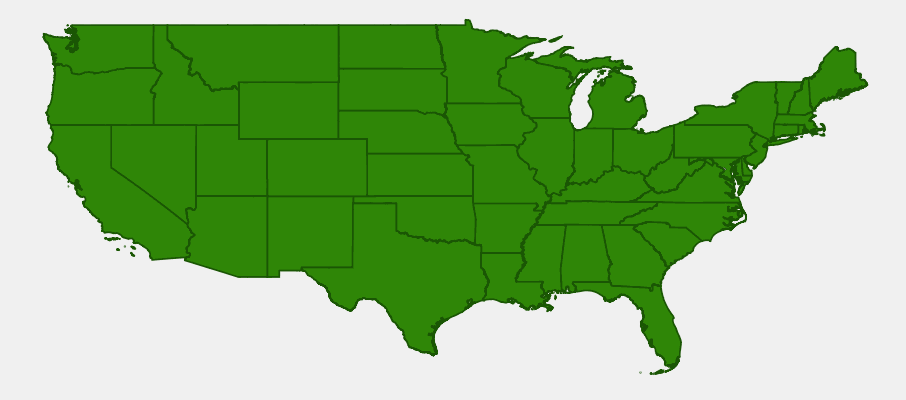

Cattail boasts one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American plant, found naturally in every U.S. state including Alaska and Hawaii, as well as throughout much of Canada from the Atlantic to the Pacific and north to the Arctic Circle. This enormous distribution reflects the plant’s remarkable adaptability to diverse climatic conditions and its ability to colonize virtually any suitable wetland habitat. Beyond North America, the species occurs throughout much of the temperate world, including Europe, Asia, and parts of Africa.

Throughout this vast range, Cattail occupies virtually every type of freshwater wetland habitat, from small farm ponds to massive prairie marshes, from roadside ditches to mountain lakes. It thrives in water depths ranging from saturated soil to several feet of standing water, showing remarkable flexibility in its water requirements. The plant is equally at home in permanent wetlands and seasonal pools, demonstrating an ability to survive both drought and flooding that few other plants can match.

Ecologically, Cattail serves as a foundational species in North American wetland ecosystems. Its dense stands create habitat structure that supports extraordinary biodiversity, while its extensive root systems help stabilize shorelines and filter water. The plant’s ability to rapidly colonize disturbed wetlands has made it invaluable for natural ecosystem recovery, though this same aggressive growth can sometimes lead to concerns about native plant diversity in small or isolated wetlands.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Cattail: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Cattail is among the easiest native plants to grow, requiring only consistently wet conditions and full sun to thrive. Its aggressive growth habit means it’s best suited for large spaces, natural areas, or water features where its spreading tendency is desired rather than problematic.

Light

Cattail performs best in full sun, where it develops the most robust growth and flowers most prolifically. It will tolerate partial shade but may become less vigorous and produce fewer flower spikes. In shaded conditions, the plants may also become more prone to flopping over, particularly in windy locations. For best results, provide at least 6 hours of direct sunlight daily.

Soil & Water

The key to growing Cattail successfully is providing consistently wet conditions. The plant thrives in everything from saturated soil to several feet of standing water, making it perfect for pond edges, bog gardens, rain gardens, and low-lying areas that stay wet. Cattail is remarkably tolerant of different soil types, growing well in clay, silt, sand, or organic muck, though it prefers nutrient-rich conditions. pH tolerance is broad (6.0-8.5), and the plant can handle both fresh water and slightly brackish conditions.

Planting Tips

Cattail can be established from rhizome divisions, container plants, or seeds. Rhizome divisions are the most reliable method — plant them in spring in 2-6 inches of water or in saturated soil. If planting from containers, gradually acclimate plants to deeper water over several weeks. Seeds can be scattered on muddy surfaces in fall or spring, but germination can be erratic. Plant only where aggressive spreading is acceptable, as Cattail can quickly dominate small water features.

Pruning & Maintenance

Cattail requires minimal maintenance in appropriate settings. Cut back old growth in late winter or early spring before new shoots emerge, though many gardeners prefer to leave some stands for winter wildlife habitat and visual interest. To control spread, physically remove unwanted rhizomes or install root barriers. In small water features, annual division may be necessary to prevent the plant from taking over entirely.

Landscape Uses

Cattail’s specific water requirements limit its landscape applications, but where appropriate, it’s exceptionally valuable:

- Pond and lake edges — classic choice for naturalizing water features

- Rain gardens — excellent for areas with standing water

- Constructed wetlands — valuable for water treatment and filtration

- Wildlife habitat — provides nesting and feeding areas for wetland species

- Erosion control — stabilizes shorelines and wet slopes

- Privacy screening — creates dense, tall screens in wet areas

- Restoration projects — helps establish wetland plant communities

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Cattail ranks among North America’s most important wildlife plants, supporting an extraordinary diversity of species throughout the year. Its dense stands create complex three-dimensional habitat that provides food, nesting sites, shelter, and nursery areas for hundreds of species.

For Birds

Cattail marshes are legendary for their bird diversity. Red-winged Blackbirds build their nests directly on cattail stems, while Marsh Wrens weave intricate globe-shaped nests among the leaves. Great Blue Herons, American Bitterns, and various rail species use cattail stands for both nesting and foraging. Waterfowl including Mallards, Blue-winged Teal, and Canada Geese nest in the dense cover, while numerous migrant species use cattail marshes as stopover habitat. The seeds feed finches, sparrows, and other seed-eating birds throughout fall and winter.

For Mammals

Muskrats are perhaps the most closely associated mammal, using cattail for both food and building materials for their lodges and push-ups. Beavers consume the rhizomes and use the stems for dam construction, while various mice and voles nest in the dense stands and feed on the seeds. White-tailed Deer wade into cattail marshes to feed on the tender shoots and rhizomes, and even Black Bears occasionally consume the starchy rootstocks.

For Pollinators

While cattail is wind-pollinated, the pollen-rich male flowers attract numerous flies and small bees. More importantly, the complex habitat structure of cattail stands supports the complete life cycles of many insects that are crucial food sources for other wildlife. The plant provides both adult habitat and larval host sites for numerous moths, including several species that are wetland specialists.

Ecosystem Role

Cattail serves as a fundamental ecosystem engineer in North American wetlands. Its extensive rhizome system helps oxygenate sediments and provides habitat for countless invertebrates. The dense stands slow water flow, allowing sediments to settle and improving water quality. During photosynthesis, cattail produces oxygen that supports fish and other aquatic organisms, while the decaying plant material forms the base of wetland food webs. The plant’s ability to absorb nutrients helps prevent eutrophication in many water bodies.

Cultural & Historical Uses

No North American plant has served human needs more comprehensively than Cattail, earning it the well-deserved nickname “supermarket of the swamp” among ethnobotanists. Virtually every Indigenous culture throughout the plant’s range developed extensive uses for different parts of cattail, making it one of the continent’s most important survival and subsistence plants. The plant provided food, medicine, tools, building materials, and ceremonial items — essentially everything needed for human life.

The food uses alone are remarkable in their diversity. Young shoots harvested in spring were eaten raw or cooked like asparagus, providing crucial vitamins after long winters. The flower spikes were harvested when young and green, then boiled and eaten like corn on the cob — a practice that continued among European settlers well into the 20th century. The pollen was collected by shaking the male flower spikes into baskets, then used as a protein-rich flour additive. Most importantly, the starchy rhizomes were processed into flour, providing a reliable carbohydrate source that could be dried and stored for winter use.

Beyond food, cattail provided materials for countless practical applications. The long, tough leaves were woven into mats, baskets, temporary shelters, and sleeping surfaces. The fluffy seed material served as insulation, tinder for fire-starting, diaper material for infants, and stuffing for pillows and cushions. The stems were used for arrow shafts, while the pollen had medicinal applications for treating burns and wounds. Many Plains tribes used cattail extensively for tipi construction and waterproofing.

European settlers quickly adopted many of these uses, particularly during times of hardship. During the Great Depression, cattail roots and shoots became important survival foods for rural families. Even today, the plant continues to find applications in sustainable technology — cattail fiber is being researched for everything from biodegradable packaging to building insulation, while constructed wetlands using cattail help treat wastewater in communities worldwide. The plant’s remarkable ability to remove pollutants from water has made it invaluable in modern environmental restoration projects.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will Cattail take over my pond completely?

Cattail is indeed aggressive and can dominate small water features if left unchecked. In ponds smaller than half an acre, you’ll likely need to manage it actively by removing excess rhizomes annually. Consider using root barriers or planting cattail in large containers submerged in the pond to control spread. In larger natural settings, cattail typically reaches a dynamic equilibrium with other plant species.

Can I eat cattail from my garden pond?

Yes, cattail is entirely edible and has been a human food source for thousands of years. However, only harvest from clean water sources, and be absolutely certain of identification. Young shoots (spring), flower spikes (early summer), pollen (summer), and roots (fall) are all edible when properly prepared. Always check local regulations, as some areas protect cattail stands for wildlife habitat.

How deep water can Cattail tolerate?

Cattail can grow in water from just saturated soil up to about 3-4 feet deep, with optimal growth occurring in 6-18 inches of water. Deeper water reduces vigor and flowering, while shallower water or just moist soil can work but may result in smaller plants. The plant’s extensive aerenchyma system allows it to transport oxygen to submerged roots even in relatively deep water.

Why are my Cattails not producing the brown flower spikes?

Cattail needs full sun and rich, consistently wet conditions to flower well. Plants in too much shade, poor soil, or fluctuating water levels may produce only leaves. Young plants may take a year or two to establish before flowering. If conditions are right but flowering is still poor, the plants may need more nutrients — cattail responds well to fertile conditions.

Is Cattail invasive or native?

Cattail (Typha latifolia) is native throughout most of North America, but its aggressive growth can make it seem invasive in small or altered wetlands. In natural, large wetland systems, it typically coexists with other native plants in a balanced ecosystem. However, in disturbed or nutrient-rich environments, it can become dominant and reduce plant diversity. Context matters — what’s natural in a large marsh might be problematic in a small garden pond.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Cattail?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota