Fire Cherry (Prunus pensylvanica)

Prunus pensylvanica L.f., commonly known as Fire Cherry, Pin Cherry, or Bird Cherry, stands as one of North America’s most remarkable pioneer species—a tree literally born from fire and disturbance. This small to medium-sized native cherry has earned its fiery name through its extraordinary ability to rapidly colonize areas burned by wildfire, often appearing in dense stands that create spectacular spring displays of white flowers across newly opened landscapes. As a member of the Rosaceae (rose) family, Fire Cherry bridges the gap between the harsh realities of ecosystem disturbance and the renewed beauty of forest regeneration.

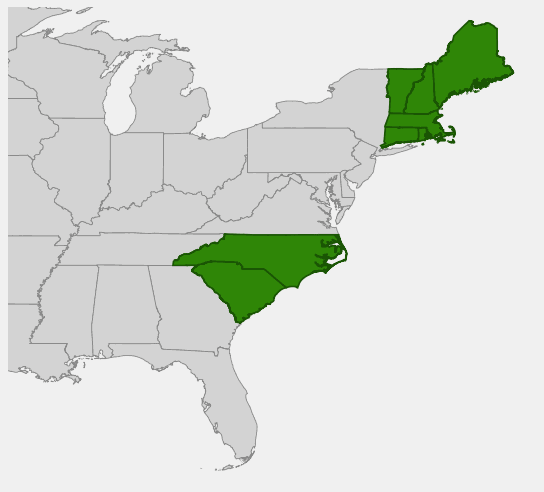

Found naturally from British Columbia east to Newfoundland and south to North Carolina and the Great Lakes region, Fire Cherry thrives in the dynamic environments where many trees struggle. Its rapid growth, abundant fruit production, and critical ecological role make it an indispensable species for wildlife, particularly during the vulnerable years following major forest disturbances. The bright red fruits ripen in summer, providing essential nutrition for over 30 species of birds at a time when many other food sources are scarce in disturbed habitats.

Though often overlooked in traditional landscaping, Fire Cherry deserves recognition as one of our most ecologically valuable native trees. Its pioneering spirit, spectacular bloom, brilliant fall color, and unmatched wildlife value make it an excellent choice for restoration projects, naturalized areas, and any garden where supporting native wildlife is a priority. Understanding Fire Cherry means understanding the resilience and regenerative power of North American forests themselves.

Identification

Fire Cherry typically grows as a small to medium-sized tree, reaching 20 to 35 feet (6–10.5 m) tall with a trunk diameter of 6 to 12 inches (15–30 cm). The growth form is distinctive: young trees have a narrow, upright crown with ascending branches, while mature specimens develop a more rounded, open canopy. Fire Cherry often grows in dense clusters from shared root systems, creating groves of closely spaced trees that can dominate disturbed sites.

Bark

The bark is smooth and reddish-brown to cherry-red on young trees and branches, giving the species part of its common name. As trees mature, the bark develops horizontal lenticels (breathing pores) that appear as light-colored dashes across the dark red surface. On older trunks, the bark becomes slightly furrowed but retains its distinctive reddish coloration. The inner bark has a bitter almond scent when cut, characteristic of wild cherries and due to the presence of cyanogenic compounds.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and narrowly oval to lanceolate, measuring 2 to 4 inches (5–10 cm) long and 1 to 1.5 inches (2.5–4 cm) wide. They taper to sharp points at both ends, with finely serrated margins featuring sharp, forward-pointing teeth. The upper surface is bright green and glossy, while the underside is paler. Two small red glands typically appear at the base of each leaf blade near the petiole. The fall color is often spectacular, ranging from bright yellow through orange to deep red, creating stunning displays in disturbed forest areas.

Flowers & Fruit

The flowers appear in late spring, usually in May, just as the leaves are emerging. They are arranged in flat-topped clusters (umbel-like corymbs) of 5 to 7 flowers, each about ½ inch (1.3 cm) across with five pure white petals and numerous stamens. The abundant flowering creates spectacular displays, especially when Fire Cherry colonizes a site in dense stands, covering entire hillsides with white blooms.

The fruit is a small drupe about ¼ inch (6 mm) in diameter, ripening from green through bright red to dark red in mid to late summer. The cherries are quite sour when eaten raw, hence the alternative name “Sour Cherry,” but they make excellent jams and jellies. The single hard stone inside each fruit contains a seed rich in compounds that give it a bitter almond flavor. Wildlife, particularly birds, eagerly consume the fruits and distribute the seeds widely, contributing to Fire Cherry’s rapid colonization abilities.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Prunus pensylvanica |

| Family | Rosaceae (Rose) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 20–35 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Bloom Time | May – June |

| Flower Color | White |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–7 |

Native Range

Fire Cherry has one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American cherry, stretching across the continent from British Columbia and Alberta east to Newfoundland and south to North Carolina, northern Georgia, and the Great Lakes region. This vast distribution reflects the species’ remarkable adaptability to diverse climatic conditions, from the harsh winters of northern Canada to the milder conditions of the southern Appalachians.

Throughout its range, Fire Cherry is characteristically a species of disturbance—appearing rapidly after wildfires, logging, storms, or other events that open the forest canopy and create the sunny conditions it requires. It thrives in areas where the organic soil layer has been removed or disturbed, often growing directly in exposed mineral soil. The species is particularly common in the boreal forests of Canada and the northern United States, where fire is a natural and frequent disturbance agent.

In the southern portion of its range, including the Carolinas and southeastern mountains, Fire Cherry typically occurs at higher elevations where cooler temperatures and occasional disturbances create suitable habitat. It is often found on north-facing slopes, in cool ravines, and in areas recovering from ice damage, severe storms, or human disturbance. The species’ ability to rapidly colonize disturbed sites makes it a critical component of early forest succession throughout its range.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Fire Cherry: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Fire Cherry is one of the easiest native trees to grow, requiring minimal care once established and thriving in conditions that challenge many other species. Its pioneer nature means it actually prefers sites that might seem inhospitable to other trees, making it an excellent choice for challenging locations or restoration projects.

Light

Fire Cherry requires full sun to partial shade for optimal growth and flowering. As a pioneer species, it is adapted to the bright conditions of recently disturbed sites and will struggle in deep shade. In full sun, trees develop dense, compact crowns with maximum flowering and fruiting. In partial shade, they become more open and may flower less abundantly but still maintain good health and growth rates.

Soil & Water

One of Fire Cherry’s greatest strengths is its tolerance for poor, disturbed soils. It actually performs best in mineral soils with organic matter removed—conditions that exist naturally after fire or other disturbances. The tree tolerates a wide pH range from acidic to slightly alkaline (4.5–7.5) and grows well in sandy, loamy, or even rocky soils as long as drainage is adequate. While drought tolerant once established, Fire Cherry grows best with consistent moisture, especially during its rapid early growth years.

Planting Tips

Plant Fire Cherry in early spring or fall in full sun locations. It transplants readily from container stock and establishes quickly. Space trees 15–20 feet apart for screening, or plant in naturalistic clusters for a more authentic pioneer forest appearance. Fire Cherry naturally forms groves through root sprouting, so consider this tendency when planning placement in the landscape.

Pruning & Maintenance

Minimal pruning is needed for Fire Cherry. Remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter while dormant. The tree naturally develops good structure and requires little training. If managing for single-trunk specimens, remove basal sprouts annually. For naturalistic plantings, allow sprouting to create authentic grove formations. Fire Cherry is generally pest and disease free but can occasionally be affected by cherry pests like borers in stressed conditions.

Landscape Uses

Fire Cherry excels in numerous landscape applications:

- Restoration sites — rapid colonization of disturbed areas

- Wildlife gardens — exceptional value for birds and pollinators

- Erosion control — stabilizes slopes and disturbed soils

- Pioneer plantings — establishes cover while slower species develop

- Naturalized areas — authentic early successional forest communities

- Rain gardens — tolerates both flooding and drought conditions

- Urban forestry — handles pollution and disturbed urban soils

- Food forests — edible cherries for humans and wildlife

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Fire Cherry ranks among the most ecologically valuable native trees in North America, serving as a crucial foundation species that supports entire communities of wildlife during the vulnerable early years of forest succession.

For Birds

The bright red cherries are consumed by over 30 species of birds, making Fire Cherry one of the most important summer food sources in disturbed habitats. Major consumers include American Robin, Cedar Waxwing, Scarlet Tanager, Rose-breasted Grosbeak, Blue Jay, and various flycatchers, thrushes, and vireos. The early summer fruit ripening coincides perfectly with fledgling season, providing critical nutrition for young birds during their most vulnerable period. The dense branching pattern also offers excellent nesting sites for numerous songbird species.

For Mammals

Black bears relish Fire Cherry fruits and will strip entire trees during peak season. Chipmunks, squirrels, and mice consume both fruits and seeds, while white-tailed deer and moose browse the twigs and foliage. The bark and young stems provide winter food for snowshoe hares, porcupines, and beavers. Fire Cherry groves create important thermal cover and security habitat for many mammals in newly disturbed forest areas.

For Pollinators

The abundant white flowers bloom during peak pollinator season, providing nectar and pollen for native bees, butterflies, and beneficial insects. Mason bees, sweat bees, and bumble bees are primary pollinators, while the flowers also attract hover flies, bee flies, and various butterfly species. Fire Cherry’s synchronized blooming with other early summer wildflowers creates crucial pollinator corridors in disturbed habitats.

Ecosystem Role

As a pioneer species, Fire Cherry plays irreplaceable roles in forest succession and ecosystem recovery. Its rapid growth and dense colonization help stabilize disturbed soils, reducing erosion and creating microclimates that facilitate establishment of later successional species. The annual leaf litter enriches soil organic matter, while nitrogen-fixing bacterial associates in the root zone improve soil fertility. Fire Cherry’s relatively short lifespan (40–60 years) means groves naturally thin over time, creating openings for longer-lived trees while maintaining structural diversity.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Fire Cherry has deep cultural significance among Indigenous peoples throughout its range, valued not only for its ecological role but also for its practical and spiritual uses. Many northern tribes, including the Ojibwe, Cree, and various Algonquian nations, recognized Fire Cherry as one of the first trees to return after wildfire, seeing it as a symbol of renewal and resilience. The Ojibwe called it okwenimizhiminagaawanzh, while the Cree knew it as pasâskominâhtik.

The tart cherries were traditionally harvested in summer and either eaten fresh or dried for winter storage. Mixed with other berries and meat, they formed part of the traditional pemmican that sustained people during long travels and harsh winters. The inner bark was used medicinally by some tribes as a treatment for coughs, stomach ailments, and as a general tonic, though it contains compounds that require careful preparation to be safe.

European settlers quickly learned to recognize Fire Cherry as an indicator of recently burned land suitable for agriculture. Early foresters noted its rapid appearance after logging operations, earning it the nickname “old field cherry.” The wood, though small in diameter, was valued for fence posts, tool handles, and fuel. During the Great Depression, Fire Cherry fruits were commonly gathered to make jellies and preserves, providing crucial nutrition for rural families.

In modern times, Fire Cherry has gained recognition from ecologists and restoration specialists as a keystone species for post-disturbance recovery. Research has shown that sites colonized by Fire Cherry recover faster and support more diverse wildlife communities than areas without pioneer tree species. The tree’s role in carbon sequestration and soil building has made it increasingly important in climate change mitigation strategies and forest carbon management programs.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it called Fire Cherry?

Fire Cherry gets its name from its remarkable ability to rapidly colonize areas after wildfires. Seeds germinate quickly in the mineral-rich ash beds left by fires, and mature trees can produce thousands of fruits that birds distribute widely, creating new colonies. It’s one of the first trees to return to burned forests, hence the “fire” connection.

Are Fire Cherry fruits edible for humans?

Yes, but they’re quite sour when eaten raw, earning another common name “Sour Cherry.” The fruits are excellent for making jams, jellies, and pies when sweetened. However, like all wild cherries, the pits contain compounds that release hydrogen cyanide when chewed, so avoid eating the seeds.

How long do Fire Cherry trees live?

Fire Cherry is relatively short-lived compared to other forest trees, typically living 40–60 years. This fits its ecological role as a pioneer species—it grows quickly, produces abundant fruit for wildlife, and then gives way to longer-lived trees like maples and oaks as the forest matures.

Will Fire Cherry take over my garden?

Fire Cherry can spread through root suckers and abundant seed production, so it may form small groves if conditions are favorable. However, it generally requires full sun and disturbed soil to establish, so it’s unlikely to invade well-established garden beds. Regular mowing around planted specimens will control spreading if desired.

When do Fire Cherries bloom in the Carolinas?

In North Carolina and South Carolina, Fire Cherry typically blooms in late April to May at higher elevations in the mountains, where the species is most commonly found. The blooming period is relatively brief, lasting about 2–3 weeks, but the display is spectacular when trees are in dense stands.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Fire Cherry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina