Leadplant (Amorpha canescens)

Amorpha canescens, commonly known as Leadplant, is one of the most distinctive and ecologically important native shrubs of the Great Plains and upper Midwest. This remarkable member of the legume family (Fabaceae) earned its unusual common name from early settlers who believed its silvery, lead-colored foliage indicated the presence of lead ore beneath the soil — a myth, but one that speaks to the plant’s unmistakable appearance on the prairie landscape. What makes Leadplant truly extraordinary is not its supposed mineral associations, but its crucial role as a nitrogen-fixing pioneer species that helps build healthy prairie ecosystems from the ground up.

Growing 1–3 feet tall, Leadplant presents a stunning visual contrast with its silvery-gray, densely hairy foliage and deep purple flower spikes that seem to glow with an almost iridescent quality in the prairie sunlight. The flowers are particularly remarkable — each tiny bloom has a deep purple banner petal surrounding bright orange stamens, creating a rich color combination found in few other native plants. These dense terminal spikes bloom from midsummer through early fall, providing crucial nectar resources when many other prairie flowers have finished blooming.

Beyond its striking beauty, Leadplant serves as a cornerstone species in prairie restoration and native landscaping. Its deep taproot — often extending 15 feet or more into the soil — helps break up compacted earth while its nitrogen-fixing root nodules enrich the soil for surrounding plants. This combination of drought tolerance, soil improvement capabilities, and exceptional wildlife value makes Leadplant an essential choice for prairie gardens, naturalized landscapes, and anyone seeking to recreate the authentic beauty and ecological function of North American grasslands.

Identification

Leadplant is easily distinguished from other prairie shrubs by its distinctive silvery foliage and unique flower structure. Once you’ve seen it, the combination of gray-green leaves and iridescent purple flower spikes makes it unmistakable on the prairie landscape.

Leaves & Stems

The leaves are alternate and pinnately compound, typically 2–4 inches long, with 15–45 small leaflets arranged along the central rachis. Each leaflet is oval to oblong, about ¼ to ½ inch long, with smooth edges (entire margins). The entire plant is covered with dense, fine, white to grayish hairs (pubescence) that give it the characteristic silvery or “lead-colored” appearance that inspired the common name. Young stems are also densely hairy and appear almost white, gradually becoming less pubescent and more brownish with age.

Flowers

The flowers are perhaps Leadplant’s most remarkable feature. They appear in dense, terminal spikes 2–6 inches long, with individual flowers clustered tightly along the spike. Each tiny flower has a deep purple to violet banner petal (the only petal present) surrounding bright orange-yellow stamens, creating an almost iridescent effect. Unlike typical legume flowers, Leadplant flowers lack wings and keel petals, having only the single banner petal. The flowering period extends from June through August, often continuing into September in favorable years.

Growth Form

Leadplant forms a low, rounded to somewhat irregular shrub, typically 1–3 feet tall and equally wide at maturity. The growth habit is dense and bushy when grown in full sun, becoming more open and leggy in partial shade. The plant spreads slowly through underground rhizomes, eventually forming small colonies, but it is not aggressive or invasive in its spread.

Root System

Like many prairie plants, Leadplant’s most impressive feature may be underground. The primary root system consists of a deep taproot that can extend 15 feet or more into the soil, allowing the plant to access deep water and nutrients while helping break up compacted subsoil layers. The roots form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria in specialized nodules, enabling the plant to convert atmospheric nitrogen into forms that other plants can use.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Amorpha canescens |

| Family | Fabaceae (Legume) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 1–3 ft |

| Growth Rate | Slow to Moderate |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate (drought tolerant) |

| Soil Type | Well-drained; tolerates poor, sandy, or clay soils |

| Soil pH | 6.0–8.0 (neutral to alkaline) |

| Bloom Time | June – September |

| Flower Color | Deep Purple with Orange Stamens |

| Special Features | Nitrogen-fixing, extremely drought tolerant |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–9 |

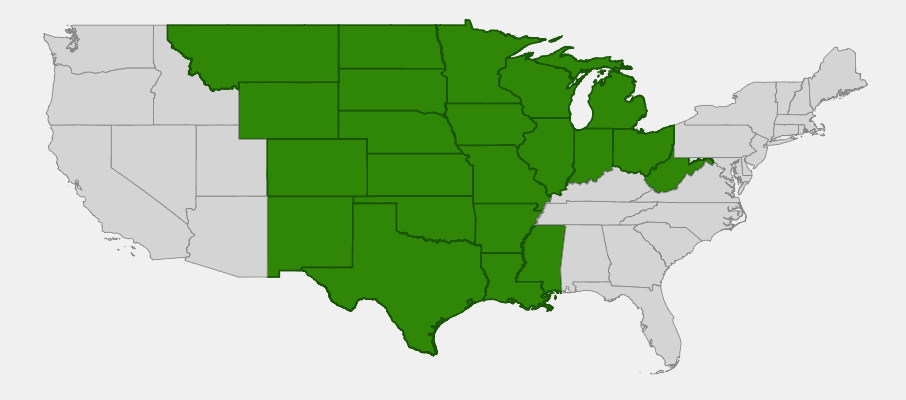

Native Range

Leadplant has a distinctive native distribution centered on the Great Plains and extending into portions of the upper Midwest, reflecting its adaptation to the continental climate and grassland ecosystems of central North America. The species ranges from southern Canada south to Texas and Louisiana, and from the Rocky Mountain foothills east to Indiana and Ohio. This distribution follows the historic tallgrass and mixed-grass prairie regions, where Leadplant served as a characteristic shrub component in the complex mosaic of grasses, forbs, and scattered woody plants that defined these ecosystems.

Throughout its range, Leadplant typically inhabits well-drained prairies, open woodlands, and hillsides where its deep root system can access groundwater while its drought-adapted foliage tolerates the intense sun and periodic dry conditions characteristic of continental grasslands. The species is particularly abundant in areas with calcareous or neutral to alkaline soils, though it adapts to a wide range of soil conditions as long as drainage is adequate. Leadplant often occurs in association with other nitrogen-fixing legumes and serves as an indicator species for high-quality grassland habitat.

Historical overgrazing, agricultural conversion, and fire suppression significantly reduced Leadplant populations across much of its range during the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, growing interest in prairie restoration and native plant gardening has led to increased cultivation and replanting efforts. The species responds well to restoration techniques including controlled burning and mechanical treatments that mimic historical disturbance patterns, making it a key component in efforts to recreate authentic prairie ecosystems.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Leadplant: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Leadplant is one of the most resilient and low-maintenance native shrubs once established, but it requires patience and understanding of its prairie origins to achieve success. The key to growing healthy Leadplant lies in providing conditions that mimic its natural grassland habitat: full sun, well-drained soil, and minimal supplemental water once established.

Light Requirements

Leadplant absolutely requires full sun to thrive. In partial shade, the plant becomes leggy, produces fewer flowers, and may eventually decline. The dense, silvery foliage is specifically adapted to reflect intense prairie sunlight, and without full sun exposure, this adaptation becomes a disadvantage rather than an asset.

Soil Preferences

One of Leadplant’s greatest strengths is its soil adaptability, as long as drainage is adequate. The plant tolerates everything from sandy to clay soils and shows particular affinity for neutral to alkaline conditions (pH 6.0–8.0). It actually performs better in lean, low-fertility soils than in rich garden beds, as excessive fertility can lead to soft, weak growth and reduced flowering. Avoid heavy, constantly moist soils, which can cause root rot.

Water Requirements

Once established, Leadplant is extremely drought tolerant and rarely requires supplemental watering in most climates. The deep taproot allows it to access moisture far below the surface, making it ideal for xeriscaping and low-water landscapes. Young plants benefit from occasional deep watering during their first growing season to encourage deep root development, but overwatering is more problematic than underwatering.

Planting & Establishment

Plant Leadplant in spring after the last frost, choosing a location with full sun and excellent drainage. Space plants 2–3 feet apart if creating a mass planting. Young plants grow slowly the first year as they focus energy on developing their extensive root system — this is normal and not a sign of poor health. Be patient with establishment; Leadplant often takes 2–3 years to reach its full flowering potential.

Pruning & Maintenance

Leadplant requires minimal maintenance once established. In late winter or early spring, cut the plant back to 6–8 inches above ground level to encourage dense, bushy growth and abundant flowering. This annual pruning mimics the natural prairie fire cycle that Leadplant evolved with. Deadheading spent flowers can prolong the blooming period but is not necessary for plant health.

Prairie Fire Management

If you’re managing a prairie or large naturalized area, Leadplant benefits greatly from periodic prescribed burns every 2–4 years. Fire removes accumulated dead material, reduces competition from cool-season grasses, and stimulates vigorous new growth and increased flowering. In smaller garden settings, the annual pruning serves a similar function.

Landscape Applications

Leadplant excels in specific landscape situations:

- Prairie gardens — essential component of authentic grassland restorations

- Xeriscaping — excellent drought tolerance for water-wise landscapes

- Pollinator gardens — long blooming period supports late-season pollinators

- Slopes and difficult sites — deep roots provide erosion control

- Native plant borders — adds structure and color to wildflower plantings

- Wildlife habitat — seeds and foliage support various prairie species

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Leadplant provides exceptional wildlife value throughout the growing season, serving as both a crucial pollinator plant and an important food source for wildlife in grassland ecosystems. Its long flowering period and nitrogen-fixing capabilities make it a keystone species that supports the broader ecological community of native prairies.

For Pollinators

Leadplant is one of the most important late-season pollinator plants in prairie ecosystems. The dense flower spikes bloom from midsummer through early fall, providing nectar when many other prairie flowers have finished blooming. Native bees, including numerous specialist species, depend heavily on Leadplant nectar, while the bright orange pollen is easily visible on visiting insects. Butterflies, particularly skippers and smaller species, also frequent the flowers, and the plant supports several moth species as larvae.

For Birds

Many grassland birds consume Leadplant seeds, including various sparrows, finches, and quail. The dense, low-growing shrubs also provide crucial nesting habitat and cover for ground-nesting species like Greater Prairie-Chickens and various grassland sparrows. In winter, the persistent seed heads continue to provide food resources, while the branching structure offers protection from wind and predators.

For Mammals

White-tailed deer and elk browse Leadplant foliage, particularly young shoots, though the plant’s deep root system allows it to recover quickly from grazing pressure. Small mammals including rabbits and ground squirrels consume both the seeds and tender foliage, while the dense growth provides cover and nesting sites for various rodent species that form the prey base for grassland predators.

Nitrogen Fixation & Soil Improvement

As a member of the legume family, Leadplant forms symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria in root nodules, converting atmospheric nitrogen into forms that other plants can utilize. This process enriches the soil and supports the diverse plant communities characteristic of high-quality prairie ecosystems. The deep taproot also helps break up compacted soils and brings deep nutrients to the surface through leaf litter decomposition.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Leadplant holds significant cultural importance in the history of Great Plains settlement and Indigenous peoples’ traditional ecological knowledge. The plant’s distinctive appearance and prairie habitat made it a well-known landmark for early travelers crossing the grasslands, while its supposed association with lead deposits created considerable excitement (and eventual disappointment) among early prospectors and settlers. This mineral connection, though scientifically unfounded, demonstrates how dramatically the plant’s unique silvery appearance stood out against the green prairie landscape.

Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains utilized Leadplant for various medicinal purposes, with different tribes developing distinct applications for the plant’s therapeutic properties. The leaves were commonly used to make teas for treating respiratory ailments, digestive issues, and general weakness. Some tribes used Leadplant preparations externally for treating wounds, skin conditions, and rheumatic pain. The plant’s reputation as a strengthening herb led to its use in traditional remedies designed to build stamina and endurance — properties that may relate to the plant’s own remarkable drought tolerance and persistence.

European settlers and early botanists were fascinated by Leadplant’s unusual flowers and silvery foliage, leading to its inclusion in many 19th-century botanical studies and horticultural collections. The plant’s association with “indicators of mineral wealth” contributed to various folk beliefs about soil quality and underground resources, though modern soil science has disproven these connections. Despite these misconceptions, early settlers often used Leadplant’s presence as a reliable indicator of deep, well-drained soils suitable for agriculture.

In contemporary times, Leadplant has become a symbol of prairie conservation and restoration efforts. Its presence in remnant prairie sites often indicates high-quality grassland habitat that has escaped agricultural conversion, making it valuable to ecologists and conservationists assessing ecosystem health. The species plays a prominent role in prairie restoration projects throughout the Midwest, where its nitrogen-fixing capabilities and deep roots make it particularly valuable for rebuilding degraded grassland soils and plant communities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is my Leadplant growing so slowly?

Leadplant naturally grows slowly, especially in its first 1–2 years as it develops its extensive deep root system. This is completely normal behavior. The plant is investing energy underground rather than in visible top growth. Once established, growth rate increases, and the deep roots provide exceptional drought tolerance and longevity. Be patient — good things take time with prairie plants!

Does Leadplant really indicate lead ore in the soil?

No, this is a historical myth. Early settlers believed the plant’s silvery, “lead-colored” foliage indicated underground lead deposits, but there’s no scientific basis for this connection. The silvery color comes from dense hairs that help the plant conserve water and reflect intense sunlight — adaptations for prairie survival, not mineral indicators.

Can I grow Leadplant in shade or partial sun?

Leadplant requires full sun to thrive and will perform poorly in partial shade. In reduced light, the plant becomes leggy, flowers poorly, and may eventually decline. The silvery foliage is specifically adapted for intense prairie sunlight, and without full sun, this becomes a disadvantage rather than an asset.

How deep do Leadplant roots really grow?

Leadplant can develop taproots extending 15 feet or more into the soil — sometimes deeper than the plant is tall! This extensive root system is what makes the plant so drought tolerant and valuable for erosion control. The deep roots also help break up compacted subsoil and access nutrients and water unavailable to shallow-rooted plants.

When should I prune Leadplant, and how much?

Prune Leadplant in late winter or early spring (February–March) by cutting the entire plant back to 6–8 inches above ground level. This annual pruning encourages dense, bushy growth and abundant flowering while mimicking the natural prairie fire cycle the plant evolved with. Don’t be afraid to cut it back hard — the plant will respond with vigorous new growth.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Leadplant?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota