Speckled Alder (Alnus rugosa)

Alnus rugosa (also treated as Alnus incana subsp. rugosa), commonly called Speckled Alder or Tag Alder, is a native large shrub or small tree that plays an outsized ecological role in the wetland and riparian ecosystems of northeastern North America. A member of the birch family (Betulaceae), Speckled Alder is one of the most ecologically significant nitrogen-fixing woody plants in the northeastern United States — its root nodules host the actinomycete bacterium Frankia, which converts atmospheric nitrogen into plant-available forms, dramatically enriching the poor, waterlogged soils of streambanks and wetland margins where this species thrives.

Speckled Alder gets its evocative common name from the pale, corky lenticels (breathing pores) that speckle its smooth, grayish-brown bark — a reliable year-round identification feature. In late winter (February to March), the plant produces long, dangling yellow-brown male catkins that are among the very first native “flowers” to appear, sometimes emerging while snow still covers the ground. These early catkins provide a critical food source for native bees and early-emerging insects, and their appearance is a beloved harbinger of spring in the northeastern landscape.

For ecological restoration, riparian revegetation, and wildlife-focused native plant gardens in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, Speckled Alder is exceptionally valuable. It stabilizes eroding streambanks, shades waterways to maintain cool temperatures for cold-water fish, improves soil fertility through nitrogen fixation, and supports dozens of wildlife species from beaver to American Woodcock. Its ability to thrive in wet, cold, and difficult-to-plant sites makes it one of the most useful native plants for challenging riparian conditions.

Identification

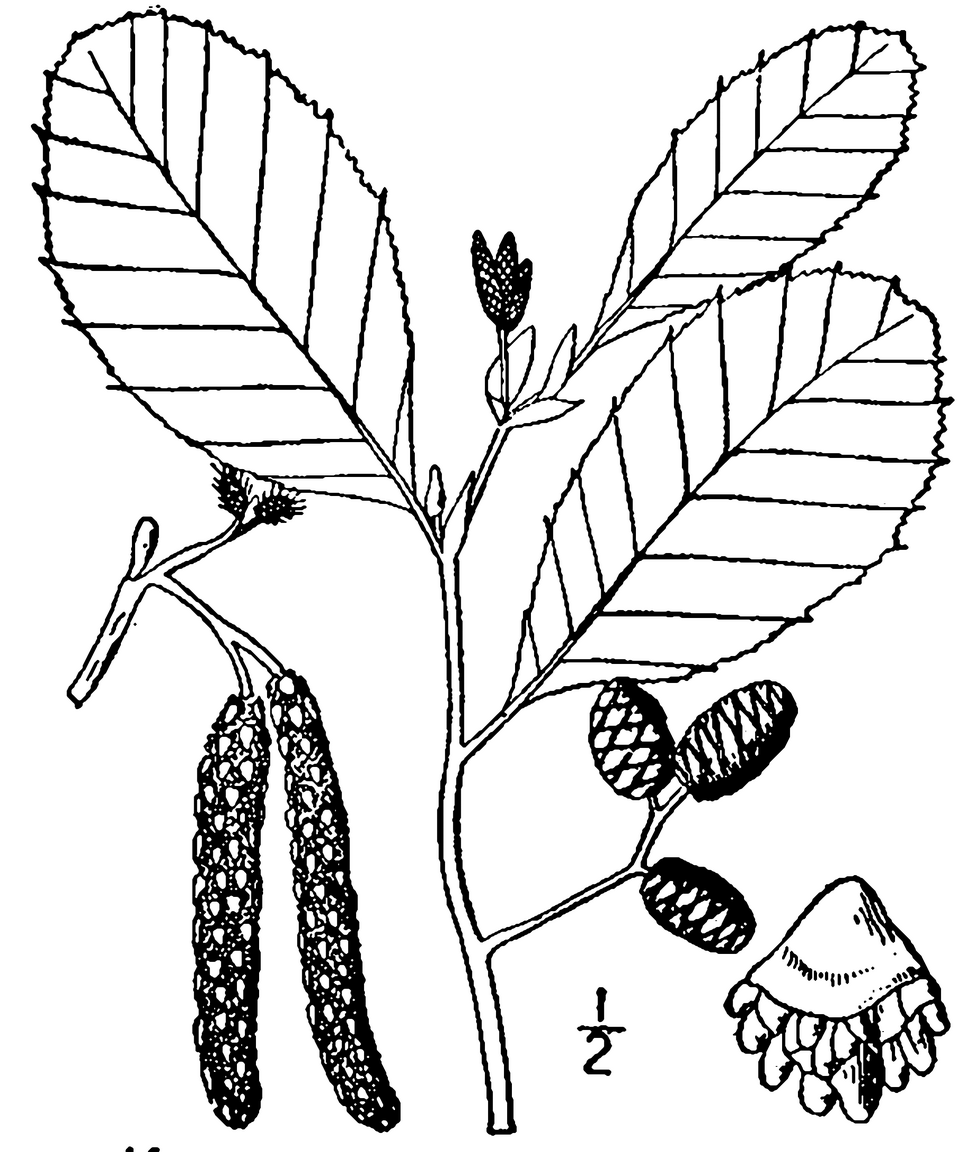

Speckled Alder grows as a large, multi-stemmed shrub or small tree, typically reaching 15 to 25 feet tall and forming dense thickets by sprouting from the base and by layering (stem tips rooting when they touch moist soil). The bark is the plant’s most distinctive feature: smooth, grayish to dark reddish-brown, and liberally dotted with pale yellowish or whitish corky lenticels — the “speckles.” Young stems also show this characteristic speckling. The overall growth habit is open and somewhat irregular, with multiple arching stems radiating from a suckering base.

Leaves

The leaves are alternate, broadly oval to elliptical, 2 to 4 inches long with doubly-toothed margins (small teeth riding on larger teeth) and a somewhat wrinkled or rugose (rough) texture — the source of the species name rugosa. They are dark green above and lighter green below, with tufts of hair in the vein axils beneath. Leaves emerge in April after the catkins have finished, and remain dark green through summer before dropping in fall without significant color change.

Catkins & Fruit

Like all alders, Speckled Alder produces separate male and female catkins on the same plant. The male catkins are long (1.5–3 inches), pendulous, and yellow-brown in color, hanging in clusters of 2–5 at branch tips. They develop in summer, overwinter as small closed structures, and expand and shed pollen in late February through April — well before the leaves emerge. The female catkins are smaller and erect, developing alongside the male catkins in spring and maturing over summer into persistent, woody, cone-like structures ½ to ¾ inch long. These dark brown “cones” remain on the plant through winter, releasing small, winged seeds that are dispersed by wind and water.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Alnus rugosa (syn. Alnus incana subsp. rugosa) |

| Family | Betulaceae (Birch) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub / Small Tree |

| Mature Height | 15–25 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Bloom Time | February – April (catkins) |

| Flower Color | Yellow-brown (male catkins) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–7 |

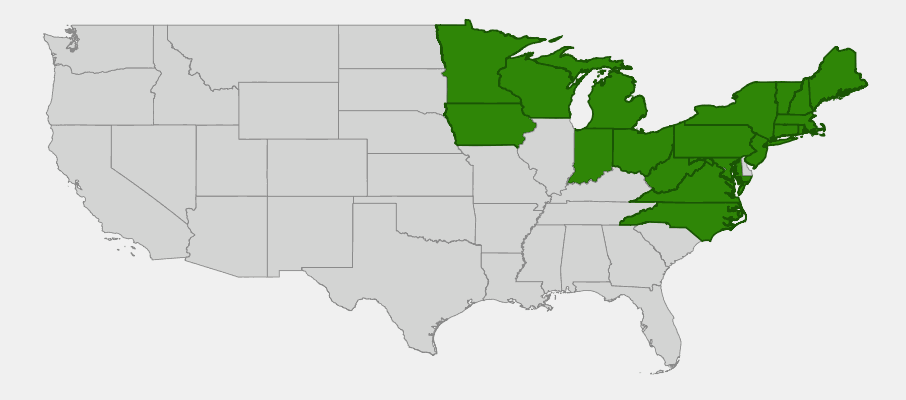

Native Range

Speckled Alder is native to northeastern North America, ranging from Newfoundland and Labrador south through New England, the Mid-Atlantic states, and into the upper Midwest. Its range in the United States extends from Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania southward through Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia, and westward through Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa. It is most abundant in the northern portions of this range and becomes less common southward.

In its natural habitat, Speckled Alder is almost always found in association with water — along stream banks, lake shores, bog edges, and in shrub swamps and wet meadows where the water table remains high through most of the growing season. It is rarely found on dry upland sites. The species is a successional pioneer in disturbed, moist habitats and is often one of the first woody plants to colonize abandoned beaver ponds, drained wetlands, and other sites where mineral soil is exposed and moisture is plentiful. Its nitrogen-fixing symbiosis with Frankia bacteria gives it a competitive advantage in the nutrient-poor soils of these early-successional wetland habitats.

Speckled Alder’s capacity for nitrogen fixation is a central ecological attribute. In nitrogen-poor wetland soils, alder thickets dramatically increase soil fertility over time, creating conditions that support a richer, more diverse plant community than would otherwise develop. This “nurse plant” function drives succession — the enriched soil beneath mature alder thickets supports colonization by willows, dogwoods, and eventually tree species, gradually transitioning from open shrub swamp toward forested wetland. American Woodcock — a declining shorebird of early-successional forest — depend heavily on Speckled Alder thickets as singing grounds, feeding habitat, and nesting cover.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Speckled Alder: New York, Pennsylvania & New Jersey

Growing & Care Guide

Speckled Alder is a tough, adaptable native plant that thrives where most ornamentals struggle — in wet, cold, and difficult riparian conditions. Its main requirement is consistent moisture; beyond that, it is remarkably self-sufficient and requires little care once established.

Light

Speckled Alder grows best in full sun to part shade. It achieves its densest growth, most prolific catkin production, and best wildlife value in full sun with adequate moisture. In part shade — such as the edge of a wooded wetland — it grows somewhat more openly and with less vigor but remains healthy and valuable. In deep shade, it declines. For restoration plantings along streams and wetland edges, site Speckled Alder in the sunniest available positions along the water’s edge.

Soil & Water

Consistent moisture is non-negotiable for Speckled Alder. It thrives in wet, heavy, and even periodically flooded soils — conditions that would kill most shrubs. It grows naturally in soils that range from saturated muck to moist but well-drained loam, as long as the water table remains high through the growing season. It tolerates acidic soils (pH 4.5–7.0) and is one of the few shrubs that can establish readily in the nutrient-poor, acidic conditions of sphagnum bog edges. Avoid dry, upland sites entirely — without consistent moisture, Speckled Alder will not thrive.

Planting Tips

Plant Speckled Alder in fall or early spring while the soil is moist. Container-grown plants establish more reliably than bare-root stock in garden settings. Space plants 8 to 12 feet apart for naturalistic plantings, or closer for erosion control along streambanks. For riparian restoration projects, Speckled Alder is often planted in conjunction with native willows, Red-osier Dogwood, and Buttonbush to create a diverse, multi-layered riparian buffer. The plant spreads by suckering and will gradually form a thicket over time — factor in this eventual spread when siting plants in smaller gardens.

Pruning & Maintenance

Speckled Alder requires minimal care once established. If you want to maintain a shrubby form and prevent thicket development, remove suckers as they appear in spring and summer. Occasional rejuvenation pruning — cutting the entire plant back to the ground every 5–10 years — produces vigorous new growth and renews the thicket. Speckled Alder is generally free of serious pest and disease problems, though it is occasionally affected by alder leaf beetles and tent caterpillars. These rarely cause permanent harm to established plants and generally do not require treatment.

Landscape Uses

- Riparian restoration — critical for streambank stabilization and water quality

- Wetland planting — one of few native shrubs that thrives in flooded conditions

- Wildlife habitat planting — especially valuable for American Woodcock and waterfowl

- Rain garden overflow areas — tolerates periodic inundation

- Naturalistic screening — dense thickets provide effective privacy screening

- Soil improvement — nitrogen fixation benefits neighboring plants

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Few native shrubs provide as much concentrated ecological value per square foot as Speckled Alder. Its early catkins, dense structure, seeds, and nitrogen-fixing capacity support a remarkable diversity of wildlife across all seasons.

For Birds

American Woodcock — a beloved and declining native shorebird — depends heavily on Speckled Alder thickets. The moist soils beneath alder stands are prime earthworm habitat, and Woodcock probe for earthworms in the soft soil of alder thickets throughout the day, nesting and roosting within the dense cover. Male Woodcock perform their spectacular aerial courtship displays (“sky dances”) at dusk in spring above alder openings. The persistent woody seed cones provide food for Common Redpolls, Pine Siskins, and American Goldfinches in winter. The dense thickets provide nesting habitat for Yellow Warblers, Common Yellowthroats, Swamp Sparrows, and Willow Flycatchers. Ruffed Grouse consume the catkins in winter as important emergency food during cold snaps.

For Mammals

Beaver are the most significant mammal consumers of Speckled Alder — they harvest the stems for dam construction and food caches, and browse the bark and twigs through winter. Muskrat also consume alder stems. Moose browse the foliage and twigs extensively in the northern part of the range, and white-tailed deer browse young plants. The dense thickets provide essential cover for snowshoe hare in northern forests, and their seasonal abundance relative to alder thicket density is so strong that ecologists use alder as a proxy indicator for snowshoe hare habitat quality.

For Pollinators

The male catkins of Speckled Alder shed pollen in late winter and early spring, often while snow still covers the ground. This early pollen is an important food source for native bees, particularly mining bees and bumblebee queens that emerge on warm late-winter days to search for food. Alder is wind-pollinated, but the pollen-rich catkins are nonetheless visited by bees seeking nutrition before other flowers are available. Bees that consume alder pollen in February and March build critical nutritional reserves that help them establish their colonies and successfully rear their first brood of the season.

Ecosystem Role

Speckled Alder is an ecosystem engineer — it physically transforms the environments it inhabits. Through nitrogen fixation, it enriches soil fertility, increasing plant diversity and productivity in the surrounding area. Its dense roots stabilize streambanks and reduce erosion, improving water clarity downstream. The shade it casts over streams maintains cool water temperatures that are critical for brook trout, Atlantic salmon, and other cold-water fish. As a successional species, it facilitates the transition from open wetland to forested wetland, driving the development of more complex and biodiverse habitats over time. Few other native shrubs have such a profound and measurable positive impact on their surrounding ecosystem.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Indigenous peoples throughout the northeastern United States and Canada had extensive uses for Speckled Alder. The Ojibwe used the inner bark as a medicinal preparation for treating skin conditions, eye infections, and as a general astringent. Various Algonquian peoples used alder bark dye — which produces a reddish-brown to orange color — to color baskets, clothing, and fishing equipment. The Iroquois used preparations of alder bark to treat hemorrhoids, skin diseases, and liver ailments. The bark of alder contains significant quantities of tannins, which account for its astringent and antimicrobial properties.

Early European settlers in North America adopted many Indigenous uses for Speckled Alder. Frontier communities used the wood as a source of charcoal for gunpowder production — alder charcoal was considered superior for this purpose due to its even burning characteristics. The wood was also used for small-scale woodworking, tool handles, and as a smoking wood for meats and fish. The Adirondack region of New York had significant commercial alder harvesting in the 19th century, with the bark being sold to tanneries and dye houses. Speckled Alder thickets were also recognized early by settlers as indicators of fertile, moist soils suitable for clearing and farming.

In contemporary conservation and restoration ecology, Speckled Alder has gained recognition as one of the most valuable native shrubs for riparian buffer planting programs. State and federal conservation agencies throughout the northeastern United States actively promote its use in streambank stabilization and water quality improvement projects. Research into its nitrogen-fixing capacity has made it a model species in studies of facilitation ecology — the ways in which some species create conditions that benefit others. For gardeners and land managers in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey with wet, challenging sites, Speckled Alder offers a native solution that improves the site while supporting exceptional wildlife diversity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Speckled Alder grow in standing water?

Yes — Speckled Alder is one of the few native shrubs that tolerates prolonged flooding. It naturally grows in and around beaver ponds, river floodplains, and shrub swamps where standing water may persist for weeks at a time. Established plants can survive significant flooding events that would kill most other shrubs. For sites with seasonal flooding, it is an excellent choice.

Does Speckled Alder take over the garden?

In moist conditions, Speckled Alder spreads by suckering and can form dense thickets over time. In a naturalistic or wildlife garden setting this is desirable — the thicket structure is ecologically important. In smaller, more managed gardens, control the spread by removing suckers annually. The plant is not invasive and does not spread by runners into dry soil or compete with other vegetation in normal garden conditions.

What does “nitrogen fixing” actually mean for my garden?

Speckled Alder hosts bacteria in specialized root nodules that convert atmospheric nitrogen (which plants cannot use) into ammonium (which they can). This process enriches the soil with plant-available nitrogen — essentially acting as a natural, slow-release fertilizer. Neighboring plants benefit from this nitrogen enrichment, leading to increased plant diversity and productivity in the surrounding area. It is the same process that makes legumes like clover and beans valuable soil improvers.

How do I tell Speckled Alder apart from other alders?

The speckled bark (pale lenticels on dark bark) is the most reliable identification feature and is visible year-round. Smooth Alder (Alnus serrulata), which overlaps in range in parts of the Mid-Atlantic, has similar bark but is generally smaller and restricted to the Coastal Plain. The combination of habitat (northern, inland wetlands), speckled bark, and doubly-toothed leaves with hairy vein axils distinguishes A. rugosa reliably.

Is Speckled Alder good for American Woodcock habitat?

Absolutely — it is one of the most important plants for Woodcock habitat management. American Woodcock populations have declined significantly due to loss of young forest and shrubby early-successional habitat, and Speckled Alder thickets are a key component of productive Woodcock habitat. Conservation organizations actively recommend planting Speckled Alder as part of Woodcock habitat management plans, particularly in the northeastern states where the species faces the greatest declines.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Speckled Alder?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: New York · Pennsylvania