Trout Lily (Erythronium americanum)

Erythronium americanum, commonly known as Trout Lily, Dogtooth Violet, or Yellow Adder’s Tongue, is a charming native spring ephemeral that brings brilliant yellow blooms to the forest floor before trees leaf out. This member of the Liliaceae (lily) family is one of the most recognizable wildflowers of eastern North American woodlands, with its distinctive mottled leaves and nodding yellow flowers that appear for just a few weeks each spring.

Despite its common name, Trout Lily is not actually a lily but gets its moniker from the spotted, trout-like pattern on its leaves and the lily-like appearance of its flowers. The plant emerges from deep underground bulbs in early spring, sending up one or two distinctively mottled leaves followed by a single bright yellow flower on a delicate stem. The flower features six strongly reflexed (backward-curving) petals that reveal prominent stamens and pistil, creating an elegant, almost turban-like appearance.

Growing naturally in rich, moist deciduous forests from Nova Scotia to Florida, Trout Lily is an excellent choice for woodland gardens, shade gardens, and native plant naturalization projects throughout the Carolinas. Its early blooms provide crucial nectar for native bees and other early pollinators, while its distinctive foliage adds textural interest to shaded areas even after the flowers fade. As a spring ephemeral, it completes its entire above-ground lifecycle before the forest canopy fully develops, making it perfectly adapted to life in deciduous woodlands.

Identification

Trout Lily is a low-growing perennial herb that typically reaches 3 to 6 feet tall, arising from a deep, white, elongated bulb. The plant consists of one or two basal leaves and, when mature, a single flower on a separate stalk. Non-flowering plants produce only one leaf, while flowering specimens typically have two leaves.

Leaves

The leaves are the most distinctive feature for identification, even when the plant is not in flower. They are elliptical to lance-shaped, 3 to 8 inches (7–20 cm) long and 1 to 3 inches (2.5–7.5 cm) wide, with smooth margins and pointed tips. The most diagnostic characteristic is their mottled appearance — the leaves are bright green with irregular purplish-brown or bronze blotches and streaks that give them a marbled or spotted pattern resembling the skin of a trout. This mottling is unique among spring wildflowers and makes identification certain.

Flowers & Fruit

The solitary flower appears in early to mid-spring (March-May, depending on latitude) on a separate stem that arises between the two leaves. The flower is bright yellow, about 1 to 2 inches (2.5–5 cm) across, with six petals that curve strongly backward (reflex), giving the flower a turban-like or lily-like appearance. The petals often have reddish-brown markings on the outside. Six prominent yellow stamens and a three-parted pistil extend beyond the reflexed petals, making the flower’s reproductive structures highly visible to pollinators.

The fruit is a three-chambered capsule containing several seeds. However, most Trout Lily reproduction occurs vegetatively through underground bulb division, and many colonies consist of identical clones that may be decades or even centuries old. Plants typically must be 4-7 years old before they produce their first flower.

Growth Habit

Trout Lily emerges very early in spring, often pushing up through snow or leaf litter when soil temperatures begin to warm. The entire above-ground lifecycle is completed in just 6-8 weeks, before deciduous trees fully leaf out. By late spring or early summer, the leaves have yellowed and died back, and the plant remains completely dormant underground until the following spring.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Erythronium americanum |

| Family | Liliaceae (Lily) |

| Plant Type | Spring Ephemeral Perennial |

| Mature Height | 3–6 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | March – May |

| Flower Color | Bright Yellow |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

Native Range

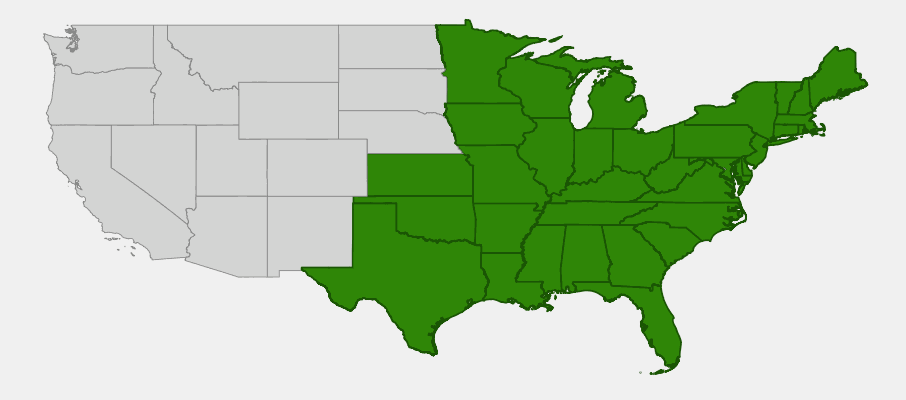

Trout Lily has one of the widest native ranges of any North American spring ephemeral, extending from Nova Scotia and southern Ontario south to Florida and west to Minnesota and eastern Texas. The species is most common in the deciduous forests of eastern North America, where it often forms extensive colonies in suitable habitat. In North Carolina and South Carolina, it can be found throughout both states, from the mountains to the coastal plain, wherever suitable deciduous forest habitat exists.

The natural habitat of Trout Lily includes rich, moist deciduous and mixed forests, particularly those dominated by maples, oaks, hickories, and other hardwoods. It thrives in areas with deep, well-drained but consistently moist soils high in organic matter, typically on slopes, in ravines, and along stream valleys where leaf litter accumulates. The plant is most abundant in mature forests with established canopies that provide the specific light conditions it requires — bright light in early spring before leaf-out, followed by deep shade during summer dormancy.

Trout Lily often grows in association with other spring ephemerals including Bloodroot, Spring Beauty, Wild Ginger, and various Trillium species. These plants have evolved similar strategies for taking advantage of the brief window of high light availability on the forest floor before trees leaf out. In optimal habitats, Trout Lily can form extensive colonies covering acres of forest floor, creating spectacular spring displays when thousands of plants bloom simultaneously.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Trout Lily: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Trout Lily can be challenging to establish in cultivation, but once settled in the right conditions, it can thrive and slowly spread to form beautiful colonies. Success depends on closely mimicking its natural forest habitat requirements.

Light

This species requires the specific light conditions found in deciduous forests — bright light during early spring (when it’s actively growing and blooming) followed by deep to partial shade during summer dormancy. Plant it under deciduous trees that will provide this natural light cycle. Avoid planting in areas that remain sunny after trees leaf out, as this will stress the plant and prevent successful establishment.

Soil & Water

Trout Lily requires rich, well-drained but consistently moist soil with high organic content. The ideal soil pH is slightly acidic to neutral (6.0–7.0). Amend heavy soils with compost, leaf mold, or other organic matter to improve drainage while maintaining moisture retention. The plant is intolerant of waterlogged conditions but also cannot survive drought. Maintain consistent soil moisture throughout the growing season, but allow natural drying during summer dormancy.

Planting Tips

Plant bulbs in fall (September-November) about 4-6 inches deep and 4-6 inches apart. Choose a location that closely matches natural forest conditions — under deciduous trees with rich, organic soil. Bulbs are often difficult to source commercially, and wild collection should never be attempted as it threatens natural populations. The best approach is often to start with purchased plants from reputable native plant nurseries. Be patient — newly planted bulbs may take 2-3 years to become fully established and may not flower for several years.

Maintenance

Trout Lily requires very little maintenance once established. Allow leaves to die back naturally — do not cut them off until they have completely yellowed and withered, as the plant needs this time to store energy in the bulb for next year’s growth. Add a thin layer of leaf mold or compost annually to maintain soil organic content. Avoid disturbing established colonies, as the bulbs are deep and easily damaged.

Landscape Uses

Trout Lily works well in several specialized applications:

- Woodland gardens as part of a spring ephemeral collection

- Naturalized forest areas for authentic native plant communities

- Spring wildflower displays combined with other early bloomers

- Educational gardens demonstrating spring ephemeral ecology

- Shade gardens for early season interest

- Wildlife habitat supporting early pollinators

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Despite its brief above-ground presence, Trout Lily plays an important role in woodland ecosystems and provides crucial resources during the critical early spring period when few other flowers are available.

For Pollinators

Trout Lily is one of the most important early nectar sources for native bees, including mining bees (Andrena), sweat bees (Halictus), and other ground-nesting species that emerge as soon as temperatures warm in spring. The flowers also attract beneficial insects such as syrphid flies and small beetles. The bright yellow flowers and prominent stamens make pollen and nectar easily accessible to a wide range of small pollinators.

For Birds

While birds don’t directly feed on Trout Lily, they benefit indirectly from the insects that the flowers attract. Early-nesting songbirds rely on the insects visiting spring ephemerals to feed their young during the critical early breeding season when other food sources are still scarce.

For Mammals

White-tailed deer occasionally browse the leaves, though the brief growing season limits this impact. Small mammals may consume the seeds when available, though most reproduction occurs vegetatively through bulb division rather than from seed.

Ecosystem Role

Trout Lily is a key component of the spring ephemeral community that characterizes eastern North American deciduous forests. These plants have evolved to take advantage of the brief period of high light availability before tree canopy development, creating a unique seasonal layer in forest ecosystems. Their early nectar production supports pollinator communities that are essential for the reproduction of many other native plants throughout the growing season.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Trout Lily has a rich history of use by Indigenous peoples throughout its range, who recognized both its medicinal properties and its role as an important early spring food source. Many Native American tribes, including the Cherokee, Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), and Ojibwe, incorporated Trout Lily into their traditional practices and seasonal diets.

The bulbs of Trout Lily are edible and were harvested by various tribes as one of the first fresh foods available after winter. The bulbs can be eaten raw but are more commonly cooked by boiling, roasting, or steaming. They have a slightly sweet, pleasant flavor and were often dried for winter storage or ground into flour. The leaves are also edible when young and were sometimes used as pot greens, though they must be cooked to remove potentially harmful compounds.

Medicinally, Trout Lily was used by many tribes to treat a variety of ailments. The Cherokee used poultices made from the crushed bulbs to treat skin problems, wounds, and swellings. The Haudenosaunee used the plant to treat scrofula (tuberculosis of the lymph nodes), and various tribes used it for internal ailments including stomach problems and respiratory issues. The plant contains saponins and other compounds that give it anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties, supporting some of these traditional uses.

European settlers learned about Trout Lily from Native Americans and incorporated it into their own folk medicine practices. The plant was listed in various pharmacopoeias and herbal guides throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, as with all ethnobotanical information, traditional uses should not be considered medical advice, and the plant should not be consumed without proper knowledge and preparation.

In modern times, Trout Lily is valued primarily for its ornamental qualities and ecological importance rather than as food or medicine. The plant has become a symbol of spring renewal and is celebrated by naturalists, botanists, and wildflower enthusiasts throughout its range. Many nature preserves and botanical gardens maintain Trout Lily populations for educational purposes and to preserve examples of natural spring ephemeral communities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it called Trout Lily if it’s not a lily?

The common name comes from the mottled, spotted pattern on the leaves that resembles the markings on trout skin, combined with the lily-like appearance of the yellow flowers. Despite the name, it’s actually a member of the true lily family (Liliaceae), so it is technically a lily, just not the type most people think of.

Can I transplant Trout Lily from the wild?

No, wild collection of Trout Lily should never be attempted. The bulbs are very deep (often 6-8 inches underground) and easily damaged, and removing plants from wild populations threatens these important native communities. Always purchase from reputable native plant nurseries that propagate plants rather than collecting them from the wild.

When do Trout Lilies bloom?

Bloom time varies with latitude and local conditions, typically occurring from March in the South to May in northern areas. The flowers last only 1-2 weeks, and the entire above-ground lifecycle is completed in 6-8 weeks before trees fully leaf out.

How long does it take for Trout Lily to establish?

Newly planted bulbs typically take 2-3 years to become fully established and may not flower for several years. Plants grown from seed can take 4-7 years to reach flowering size. Patience is essential when growing this species.

Will Trout Lily spread in my garden?

Yes, but very slowly. Established plants spread gradually through underground bulb offsets, typically expanding only a few inches per year. Large colonies representing decades or centuries of growth can eventually form, but this process takes many years in cultivation.

Looking for a nursery that carries Trout Lily?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina