American Holly (Ilex opaca)

Ilex opaca, commonly known as American Holly, is a magnificent evergreen tree that stands as one of the most iconic native species of the southeastern United States. This member of the Aquifoliaceae (holly) family is renowned for its glossy, spiny-margined leaves and brilliant red berries that provide crucial winter food for wildlife when other resources are scarce. The distinctive waxy green foliage and bright red fruit clusters have made American Holly a beloved symbol of the winter holidays, yet this remarkable tree offers far more than seasonal beauty.

Growing naturally in mixed hardwood and pine forests from southern Maine to central Florida and west to southeastern Kansas, American Holly serves as both an understory and canopy species depending on growing conditions. Mature specimens can reach heights of 20 to 40 feet with a distinctive pyramidal crown when young, becoming more rounded and open with age. The tree’s slow to moderate growth rate and exceptional longevity — specimens can live for several centuries — make it a valuable long-term addition to any native landscape.

American Holly is particularly valuable for wildlife, with its berries serving as a critical winter food source for over 20 species of birds including Cedar Waxwings, American Robins, and Wild Turkeys. The dense, evergreen foliage provides year-round shelter and nesting sites, while the tree’s dioecious nature (separate male and female trees) means that careful planning is needed to ensure berry production. For gardeners seeking a native evergreen with exceptional wildlife value, stunning winter interest, and cultural significance, American Holly represents one of the finest choices available.

Identification

American Holly is readily identified by its distinctive evergreen foliage and growth habit. Young trees typically develop a dense, pyramidal form reaching 20 to 40 feet in height, though exceptional specimens can grow to 60 feet or more in ideal conditions. The trunk can reach 1 to 2 feet in diameter, supporting a crown that becomes more open and irregular with age.

Bark

The bark of American Holly is smooth and light gray when young, gradually developing shallow furrows and becoming darker gray to nearly black with age. The inner bark has a greenish tint, and the wood beneath is nearly white, fine-grained, and extremely hard — historically prized for specialty woodworking applications including piano keys and inlay work.

Leaves

The leaves are perhaps the most distinctive feature of American Holly. They are evergreen, alternate, and elliptical to oblong in shape, measuring 2 to 4 inches long and 1 to 2 inches wide. Each leaf is thick and leathery with a waxy, glossy dark green upper surface and a paler, duller underside. The leaf margins are typically armed with sharp, rigid spines, though leaves on older trees or in shaded conditions may have fewer spines or be nearly entire. The prominent midrib and secondary veins create a distinctive pattern that remains visible year-round.

Flowers

American Holly is dioecious, meaning individual trees are either male or female. Both produce small, white to greenish-white flowers in late spring (May to June), but the flowers differ significantly between sexes. Male trees produce clusters of 3 to 12 flowers in the axils of current year’s growth, each flower having 4 petals and 4 prominent stamens. Female trees produce flowers singly or in small groups of 2 to 3, with 4 petals and a prominent central pistil surrounded by small, non-functional stamens.

Fruit

Only female trees produce the characteristic bright red drupes (berries) that American Holly is famous for. The berries are round, about ¼ inch in diameter, and contain 4 hard, ribbed seeds called pyrenes. They ripen in early fall and persist through winter, creating spectacular displays against the dark green foliage. The berries are mildly toxic to humans but are an essential wildlife food source. For fruit production, at least one male tree must be present within about 40 feet of female trees — one male can typically pollinate 2 to 3 females effectively.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Ilex opaca |

| Family | Aquifoliaceae (Holly) |

| Plant Type | Evergreen Tree |

| Mature Height | 20–40 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate |

| Bloom Time | May – June |

| Flower Color | White to greenish-white |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 6 – 9 |

Native Range

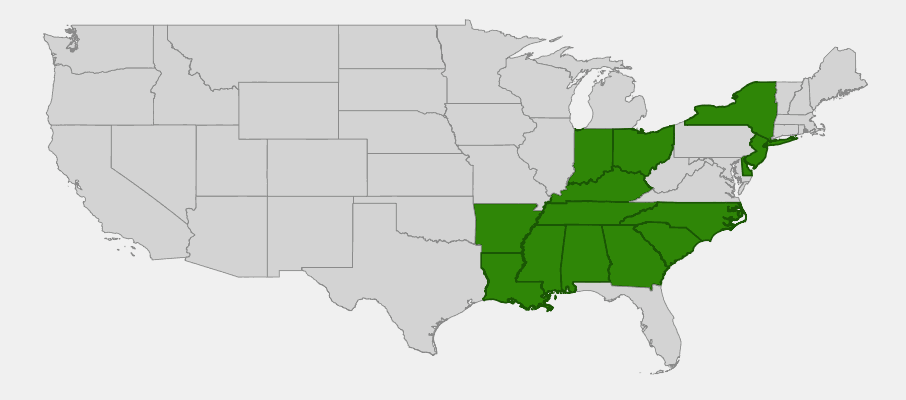

American Holly has one of the largest natural distributions of any holly species in North America, ranging from southern Maine west to southeastern Pennsylvania, south through the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plains to central Florida, and west to southeastern Kansas, eastern Oklahoma, and eastern Texas. The species reaches its greatest abundance and largest size in the southeastern United States, particularly in the Carolinas, Georgia, and northern Florida.

Throughout its range, American Holly typically grows as an understory tree in mixed deciduous and pine forests, though it can reach canopy status in favorable sites. It shows a strong preference for well-drained, acidic soils and is commonly found on sandy ridges, in bottomland hardwood forests, and along the edges of swamps and wetlands. The species is notably absent from the Appalachian Mountains above about 2,000 feet elevation, preferring the warmer conditions of lower elevations and coastal areas.

Historically, American Holly populations have experienced pressure from over-harvesting for the Christmas greenery trade, leading to local declines in some areas. However, the species remains relatively common throughout most of its range and has even expanded its distribution northward in recent decades, likely due to climate warming and reduced harvesting pressure as commercial holly farms have become the primary source for holiday decorations.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring American Holly: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

American Holly is a rewarding but somewhat challenging native tree to grow, requiring patience due to its slow growth rate and specific needs for successful establishment. Understanding its requirements and growth habits will help ensure success in the landscape.

Light

American Holly performs best in full sun to partial shade, adapting well to a range of light conditions. In full sun, trees develop a denser, more compact form with better berry production on female specimens. In partial shade, trees may grow taller and more open but will still thrive. The species is moderately shade-tolerant and can survive in deeper shade, though growth will be slower and berry production reduced.

Soil & Water

American Holly prefers well-drained, acidic soils with a pH between 5.0 and 6.5, though it can tolerate slightly alkaline conditions. The tree performs best in sandy loam or loamy soils but adapts to clay soils provided drainage is adequate — waterlogged conditions can be fatal. Once established, American Holly is quite drought tolerant, but consistent moisture during the establishment period (first 2-3 years) is crucial for success. Deep, infrequent watering is preferred over shallow, frequent irrigation.

Planting Tips

Plant American Holly in early spring or fall when temperatures are moderate. Choose container-grown specimens rather than bare-root plants, as hollies have a taproot and don’t transplant well when disturbed. Dig a hole twice as wide as the root ball but no deeper — the top of the root ball should be level with the surrounding soil. For berry production, plant one male tree for every 2-3 female trees within 40 feet of each other. Space trees 15-20 feet apart for screening or 25-30 feet apart for specimen plantings.

Pruning & Maintenance

American Holly requires minimal pruning once established. Remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter or early spring before new growth begins. The tree naturally maintains an attractive shape, but light pruning can enhance the pyramidal form if desired. Avoid heavy pruning, as hollies are slow to recover from major cuts. Young trees benefit from removal of lower branches to encourage a single trunk and tree-like form.

Landscape Uses

American Holly’s versatility makes it valuable for many landscape applications:

- Specimen tree — showcase the natural form and winter interest

- Privacy screen — plant in groups for year-round screening

- Woodland gardens — excellent understory tree for naturalized areas

- Wildlife habitat — provides food and shelter for numerous species

- Winter interest — evergreen foliage and red berries brighten dormant landscapes

- Foundation plantings — smaller specimens work well near buildings

- Urban landscapes — tolerates air pollution and compacted soils

Wildlife & Ecological Value

American Holly ranks among the most ecologically valuable native trees for wildlife, providing essential resources across multiple seasons and serving as a keystone species in many forest ecosystems.

For Birds

The bright red berries of American Holly are consumed by over 20 species of birds, with consumption peaking during late winter when other food sources are scarce. Cedar Waxwings are perhaps the most famous holly berry consumers, often arriving in large flocks to strip trees of their fruit. American Robins, Eastern Bluebirds, Hermit Thrushes, and various woodpeckers also rely heavily on holly berries. Wild Turkeys consume both the berries and seek shelter beneath the dense canopy. The evergreen foliage provides critical winter roosting and nesting sites for many bird species.

For Mammals

White-tailed Deer browse the foliage of young American Holly trees, particularly during winter months when other food is limited. Gray Squirrels and Flying Squirrels consume the berries and often nest in the dense crown. Raccoons and Opossums also eat the fruit when available. The dense, spiny foliage provides excellent cover for small mammals seeking protection from predators.

For Pollinators

While American Holly flowers are small and inconspicuous, they are visited by various native bees, including honey bees, bumblebees, and solitary bees. The flowers bloom during a period when many native plants are not yet flowering, providing an important early-season nectar source. Various small flies and other beneficial insects also visit the flowers.

Ecosystem Role

As both an understory and canopy species, American Holly plays important structural roles in forest ecosystems. Its evergreen nature provides year-round cover in deciduous forests, creating microhabitats with different light and moisture conditions. The leaf litter is slow to decompose, contributing to soil organic matter and providing habitat for invertebrates. The tree’s longevity — specimens can live several centuries — makes it a stabilizing presence in forest communities, providing consistent resources over long time periods.

Cultural & Historical Uses

American Holly holds a special place in American cultural history, serving both practical and symbolic purposes for centuries. Indigenous peoples of the southeastern United States, including Cherokee, Creek, and other tribes, used various parts of the tree for medicinal purposes. The leaves were brewed into teas for treating fever and digestive ailments, while the bark was used for various traditional remedies. The wood, being extremely hard and fine-grained, was carved into tools and ceremonial objects.

European colonists quickly recognized the resemblance between American Holly and European Holly (Ilex aquifolium), and began using it as a substitute for Christmas decorations. This practice grew into a major industry by the 19th century, with millions of branches harvested annually from wild populations across the Southeast. The town of Holly Hill, South Carolina, became a major shipping center for holly greenery, and the industry provided important income for rural families during the Great Depression.

The commercial holly trade reached its peak in the mid-20th century but began declining as concerns grew about over-harvesting of wild populations. Today, most commercial holly comes from dedicated farms rather than wild harvesting, helping to protect natural populations. The wood of American Holly, being nearly white and extremely hard, was historically prized for specialty applications including piano keys, tool handles, inlay work, and engraving blocks. During World War II, holly wood was even used for aircraft parts due to its strength and light weight.

In modern times, American Holly remains an important symbol of winter holidays and is the state tree of Delaware. Its image appears on everything from state quarters to holiday decorations, cementing its place in American cultural identity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why doesn’t my American Holly produce berries?

American Holly trees are either male or female, and only female trees produce berries. For berry production, you need at least one male tree within about 40 feet of your female trees. One male can pollinate 2-3 females. If you have both sexes present but still no berries, the trees may be too young (hollies can take 5-10 years to reach reproductive maturity) or growing in too much shade.

How fast does American Holly grow?

American Holly is a slow to moderate grower, typically adding 6-12 inches per year under good conditions. Young trees may grow more slowly until established, then pick up speed. The slow growth rate is offset by the tree’s exceptional longevity — specimens can live for several centuries.

Are holly berries poisonous?

Yes, holly berries are mildly toxic to humans and pets if consumed in quantity. They contain saponins that can cause vomiting, diarrhea, and drowsiness. However, they are an important and safe food source for birds and other wildlife. Keep berries away from young children and pets.

Can American Holly grow in alkaline soil?

While American Holly prefers acidic soil (pH 5.0-6.5), it can tolerate slightly alkaline conditions, especially if the soil is well-drained and organic matter is added. In strongly alkaline soils, the tree may show chlorosis (yellowing leaves) due to iron deficiency. Adding organic mulch and sulfur can help acidify the soil around the tree.

When should I prune my American Holly?

Prune American Holly in late winter or early spring before new growth begins (February-March in most areas). The tree requires minimal pruning — just remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches. Avoid heavy pruning as hollies are slow to recover from major cuts. Light shaping is best done on young trees to establish good form.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries American Holly?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina