Tulip Tree (Liriodendron tulipifera)

Liriodendron tulipifera, commonly known as Tulip Tree, Yellow Poplar, or Tulip Poplar, is a magnificent native deciduous tree that stands as one of the tallest and most impressive hardwoods in eastern North America. This member of the magnolia family (Magnoliaceae) is renowned for its towering height — often reaching 70–90 feet in cultivation and up to 150 feet in optimal forest conditions — along with its distinctive four-lobed leaves and spectacular tulip-shaped flowers that give the tree its common name. The large, showy blooms are yellow-green with bright orange markings and appear in late spring, creating one of nature’s most beautiful floral displays among native trees.

Native to rich, moist soils in deciduous forests throughout much of the eastern United States, Tulip Tree has earned a reputation as one of our most valuable timber species while also serving as an outstanding landscape tree for large properties. The tree’s straight trunk, rapid growth rate, and relatively few pest problems make it both economically important and horticulturally desirable. In autumn, the distinctive leaves turn a clear, bright yellow that provides excellent seasonal color against the tree’s characteristic gray, deeply furrowed bark, creating a spectacular display that can be seen from great distances.

Beyond its impressive size and ornamental qualities, Tulip Tree provides exceptional wildlife value and ecological benefits that extend far beyond its immediate vicinity. The large flowers are critical nectar sources for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds during their peak breeding season, while the abundant seeds feed numerous bird species throughout fall and winter. The tree’s massive size and longevity — potentially living 200-300 years — make it a cornerstone species in forest ecosystems, and its rapid growth makes it invaluable for carbon sequestration and large-scale reforestation projects. For gardeners with adequate space, Tulip Tree offers the rare opportunity to plant what may become a centuries-old landmark tree that will benefit wildlife, the environment, and future generations for decades to come.

Identification

Tulip Tree is easily one of the most recognizable native trees in eastern North America, thanks to its unique combination of distinctive leaves, impressive size, and characteristic growth habit. This large, fast-growing deciduous tree typically reaches 70–90 feet in height in landscape settings, though forest specimens in optimal conditions can grow even taller — up to 150 feet with trunk diameters exceeding 4 feet. The tree develops a straight, columnar trunk with a relatively narrow crown when young, gradually broadening and becoming more oval to rounded with age. Mature specimens are truly impressive, with massive trunks and expansive canopies that dominate the surrounding landscape.

Bark & Trunk

Young Tulip Trees have smooth, gray bark that provides an attractive backdrop for the distinctive foliage, but as the tree matures, the bark develops one of the most recognizable patterns among native trees. The mature bark becomes deeply furrowed with distinctive interlocking ridges that create a diamond or rectangular pattern across the trunk surface. The bark color ranges from gray to brown, and this deeply textured pattern becomes increasingly pronounced with age, especially on large mature specimens where the furrows can be several inches deep.

The trunk typically grows remarkably straight and tall, a characteristic that made Tulip Tree invaluable for timber use and continues to make it an excellent landscape specimen. This naturally straight growth habit, combined with the tree’s rapid growth rate, allows young trees to quickly establish a strong central leader and develop the classic pyramidal form that characterizes the species. Even in landscape settings, mature trees maintain their impressive straight trunks, making them excellent choices for formal or naturalistic plantings where a strong vertical element is desired.

Leaves

The leaves of Tulip Tree are absolutely unique among North American trees and provide one of the most reliable identification features year-round. They are simple, alternate, and distinctively four-lobed with a truncated (squared-off) tip that appears as if it were cut with scissors — a characteristic so distinctive that the tree can be identified by leaves alone, even at great distances. Each leaf is typically 4–6 inches long and equally wide, with two large lateral lobes, two smaller basal lobes, and the characteristic flat or slightly notched apex that gives the leaf its unmistakable silhouette.

The leaf surface is bright green above and paler green below, with prominent veining that adds to the leaf’s architectural quality. The petioles (leaf stems) are relatively long, allowing the leaves to flutter in even light breezes, creating an attractive movement in the canopy. In fall, the leaves undergo a spectacular transformation, turning a clear, bright yellow that creates one of the most striking autumn displays among native trees. This fall color is remarkably consistent across different growing conditions and persists for several weeks before the leaves drop, providing extended seasonal interest.

Flowers & Fruit

The flowers are undoubtedly the tree’s most spectacular feature and the source of its common name. These remarkable blooms are large (2–3 inches across), tulip-shaped, and colored in an striking combination of yellow-green petals with bright orange markings near the base — a color pattern that has made them among the most beloved of all native tree flowers. The six petals form a perfect cup shape that resembles a tulip flower, while the prominent orange nectar guides at the base serve to attract hummingbirds and other pollinators.

These magnificent flowers appear in late spring to early summer (typically May through June), timing their bloom to coincide with the peak activity period of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and other pollinators. While individual flowers last only a few days, the extended blooming period means the tree provides nectar resources for several weeks. Unfortunately, these spectacular blooms often occur high in the canopy where they may be difficult to see from ground level, though young trees and lower branches of mature trees may produce more visible flowers.

Following pollination, the flowers develop into distinctive cone-like structures 2–3 inches long that are composed of numerous winged seeds (samaras). These seed structures, sometimes called “candles” due to their upright position on the branches, ripen from green to brown over the course of the summer and early fall. When mature, the seeds separate and disperse on the wind, spinning like tiny helicopters as they fall — a process that can continue for several weeks and may create substantial seed litter beneath large trees.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Liriodendron tulipifera |

| Family | Magnoliaceae (Magnolia) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 70–90 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | May – June |

| Flower Color | Yellow-green with orange markings |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–9 |

Native Range

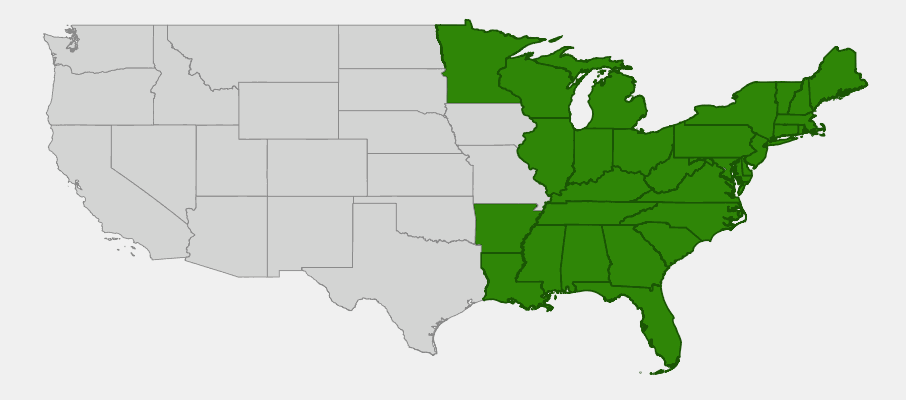

Tulip Tree boasts one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American hardwood tree, stretching from southern New England west to southern Illinois and Missouri, and south to northern Florida and the Gulf Coast states. This vast distribution reflects the species’ remarkable adaptability to the varied climatic and soil conditions found across the eastern deciduous forest biome. The tree reaches its greatest abundance and largest size in the Appalachian Mountains and adjacent regions, where the combination of rich, moist soils, adequate rainfall, and moderate temperatures provides optimal growing conditions for this magnificent species.

Throughout its extensive range, Tulip Tree is most commonly found in rich, moist, well-drained soils in forest coves, valleys, and lower mountain slopes — areas that receive consistent moisture but avoid waterlogged conditions. The species commonly occurs in mixed mesophytic forests alongside other moisture-loving hardwoods such as American Beech, Sugar Maple, White Oak, Black Cherry, and American Basswood. These forest associations represent some of the most diverse and ecologically rich plant communities in North America, with Tulip Tree often serving as one of the dominant canopy species.

The species’ extensive geographic distribution demonstrates its remarkable ecological adaptability, thriving from the relatively harsh winters of northern New England and the Great Lakes region to the subtropical conditions of northern Florida and the Gulf Coast. This adaptability, combined with the tree’s rapid growth rate and impressive size potential, has made Tulip Tree a dominant component of eastern forest ecosystems for thousands of years. Climate change research suggests that Tulip Tree’s range may be shifting northward as temperatures warm, making it an increasingly important species for forest restoration and carbon sequestration projects throughout its range.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Tulip Tree: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Tulip Tree is surprisingly easy to grow when provided with appropriate conditions that replicate its natural forest habitat. Success with this magnificent tree lies in understanding that it evolved as a dominant canopy species in rich, moist deciduous forests, where it receives full sun from above while its roots access consistently moist, fertile soils. While fast-growing and generally low-maintenance once established, Tulip Tree does have specific requirements that must be met for optimal performance and longevity.

Light

Tulip Tree absolutely requires full sun conditions to reach its full potential and develop the impressive size and form for which it is renowned. This species evolved as a dominant canopy tree in eastern deciduous forests, where mature specimens tower above surrounding vegetation and receive direct sunlight throughout the day. In landscape settings, plant Tulip Tree where it will receive at least 6–8 hours of direct sunlight daily, with preference for locations that receive morning through afternoon sun.

Insufficient light results in a cascade of problems including weak, spindly growth, poor flowering, reduced fall color intensity, and dramatically increased susceptibility to pests and diseases. Young trees can tolerate light shade temporarily during establishment, but they must eventually emerge into full sun to develop into healthy, mature specimens. The tree’s naturally rapid growth rate means it will quickly outgrow shaded conditions if planted in appropriate sites, but trees forced to grow in insufficient light will never achieve their full landscape potential.

Soil & Water

Tulip Tree performs best in deep, rich, well-drained soils that maintain consistent moisture without becoming waterlogged — conditions that mirror the fertile forest coves and valleys where the species thrives in nature. The ideal soil is a deep, loamy texture with substantial organic content and a slightly acidic to neutral pH range of 6.0–7.0. While somewhat adaptable to different soil types, Tulip Tree struggles in heavy clay soils that remain saturated for extended periods, as well as in sandy soils that drain too quickly and cannot maintain adequate moisture levels.

Consistent moderate moisture throughout the growing season is essential for optimal growth and health. The extensive root system of mature trees allows them to access deep groundwater during dry periods, but young trees require regular irrigation during establishment and benefit from supplemental watering during extended droughts even after establishment. Proper mulching with 2–3 inches of organic material such as shredded bark or leaf compost helps conserve soil moisture, moderate soil temperatures, and suppress competing weeds. Keep mulch several inches away from the trunk base to prevent moisture-related fungal problems.

Planting Tips

Timing is crucial for successful Tulip Tree establishment. Plant in early spring or fall when temperatures are moderate and natural rainfall is more dependable. This species transplants best when young, typically under 6 feet in height, as larger specimens often experience significant transplant shock due to their extensive taproot system. Select nursery stock with well-developed root systems and avoid plants that have been growing in containers too long and have developed circling roots.

Site selection is critical for long-term success. Choose a location with plenty of room for the mature tree — remember that Tulip Tree will eventually reach 70–90 feet tall with a spread of 35–50 feet, so maintain appropriate distances from buildings, power lines, sidewalks, and other structures. The ideal site receives full sun throughout the day, has deep, fertile soil with good drainage, and provides protection from strong winds that can damage the somewhat brittle wood.

When planting, dig a hole only as deep as the root ball but 2–3 times as wide to encourage lateral root development. Position the tree so the root flare is at or slightly above the surrounding soil surface — planting too deeply is one of the most common causes of establishment failure. Backfill with native soil rather than amendments, as Tulip Tree performs best when its expanding root system can transition gradually into surrounding native soil conditions.

Pruning & Maintenance

One of Tulip Tree’s greatest advantages as a landscape specimen is its naturally excellent form that requires minimal corrective pruning throughout its life. The species naturally develops a strong central leader and well-spaced branch structure that rarely requires intervention. Any pruning should be performed during the dormant season, preferably in late winter before bud break, to minimize sap flow and reduce stress on the tree.

Focus pruning efforts on removing dead, damaged, diseased, or crossing branches while the tree is young and cuts remain small. Avoid topping, heading cuts, or other severe pruning practices that can compromise the tree’s natural form and structural integrity. Young trees may benefit from light training pruning to establish good branch spacing and remove competing leaders, but mature trees should be left largely undisturbed except for necessary safety pruning.

The species is generally quite pest and disease resistant, though occasional issues with aphids, scale insects, or tulip tree scale may occur during periods of environmental stress. Maintaining proper growing conditions through adequate watering, mulching, and avoiding mechanical damage to the bark provides the best defense against pest and disease problems. Fertilization is rarely necessary if the tree is growing in reasonably fertile soil, as excessive nutrients can promote rapid, weak growth that is more susceptible to storm damage.

Landscape Uses

Tulip Tree’s impressive size and distinctive characteristics make it suitable for specific landscape applications where its remarkable qualities can be fully appreciated:

- Specimen tree — Exceptional as a focal point for large properties where its impressive stature, unique flowers, and distinctive leaves can be showcased

- Shade tree — Provides extensive cooling shade for large areas, though requires sufficient overhead clearance and space for root development

- Reforestation projects — Outstanding choice for large-scale forest restoration due to rapid growth, wildlife value, and ability to quickly establish forest canopy

- Carbon sequestration — Excellent for carbon offset projects given its fast growth rate, large mature size, and potential longevity of 200+ years

- Wildlife habitat creation — Supports diverse wildlife communities with flowers for hummingbirds, seeds for birds, and nesting sites for various species

- Parks and public spaces — Ideal for large parks, campuses, and public areas where space allows and long-term planning can accommodate mature size

- Historic landscape restoration — Appropriate for restoring historic properties and landscapes where native forest vegetation is desired

- Stream and wetland buffers — Excellent for riparian buffer plantings where deep, moist soils provide ideal growing conditions

- Legacy tree planting — Perfect for families or organizations wanting to plant a tree that will become a long-term landmark and benefit future generations

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Tulip Tree ranks among North America’s most ecologically significant native trees, providing critical resources and habitat for an extraordinary diversity of wildlife species while performing essential ecosystem functions that extend far beyond its immediate growing site. Its unique combination of large size, longevity, spectacular flowers, and abundant seed production makes it a keystone species in eastern deciduous forest ecosystems, supporting complex food webs and ecological relationships that have evolved over thousands of years.

For Birds

The spectacular flowers of Tulip Tree provide one of the most important nectar sources for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds throughout their breeding range in eastern North America. The timing of the bloom period — typically late May through June — coincides precisely with the hummingbirds’ peak energy demands during courtship displays, territory establishment, nest building, and the early stages of raising young. The large, tulip-shaped flowers are perfectly adapted to hummingbird feeding, with deep nectar wells that are accessible only to long-tongued pollinators, while the bright orange nectar guides at the flower base serve as visual attractants.

The abundant seed production of mature Tulip Trees supports numerous bird species throughout fall and winter months. The winged seeds are consumed by Northern Cardinals, Purple Finches, American Goldfinches, Carolina Chickadees, Tufted Titmice, and various woodpecker species including Red-bellied, Downy, and Hairy Woodpeckers. The large seed crops produced by mature trees can support significant bird populations, and the extended seed dispersal period — often lasting several months — provides a reliable food source during the critical fall migration and winter survival periods.

Beyond food resources, the impressive height and sturdy branching structure of mature Tulip Trees provide essential nesting sites for numerous large bird species. Red-tailed Hawks, Red-shouldered Hawks, Broad-winged Hawks, and Great Horned Owls commonly nest in the upper canopy, while Barred Owls may use hollow sections that develop in older trees. The dense summer foliage provides cover and insect-hunting opportunities for countless smaller species, while the extensive branching structure supports the stick nests of various crow and jay species.

For Mammals

White-tailed deer browse the tender leaves and young twigs of Tulip Tree, particularly during winter months when other food sources become scarce. However, the tree’s rapid growth rate typically allows it to outpace deer damage, and the somewhat bitter taste of the leaves provides natural protection against excessive browsing. Young trees in areas with high deer populations may benefit from protective fencing during the establishment period.

Eastern Gray Squirrels and Fox Squirrels are major consumers of Tulip Tree seeds, harvesting them both directly from the trees and gathering fallen seeds from the ground. These industrious mammals cache many seeds for winter consumption, inadvertently helping to disperse the species to new locations throughout the forest. The extensive seed caches created by squirrels often result in clusters of young Tulip Trees appearing in seemingly random locations, contributing to the species’ natural regeneration patterns.

Black bears occasionally feed on Tulip Tree sap and may claw bark to access the sweet cambium layer, though this rarely causes significant damage to healthy trees. The massive hollow trunks that sometimes develop in ancient Tulip Trees provide denning sites for various mammals including raccoons, opossums, and occasionally even black bears in appropriate habitats. These natural tree cavities represent some of the largest enclosed spaces available in eastern forests, supporting species that require substantial protected areas for raising young and winter shelter.

For Pollinators

While Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are the primary pollinators of Tulip Tree flowers, the large, nectar-rich blooms also attract a diverse array of insect visitors. Native bees, including various bumblebee species, carpenter bees, and smaller solitary bees, frequently visit the flowers for both nectar and the abundant pollen they produce. The large petals serve as excellent landing platforms for these insects, while the copious pollen production provides high-protein food for developing bee larvae.

Various beneficial beetles, including soldier beetles and flower longhorn beetles, commonly visit Tulip Tree flowers, where they consume both nectar and pollen while inadvertently transferring pollen between flowers. Hover flies and other beneficial insects also frequent the blooms, contributing to the complex pollination networks that ensure consistent seed production. The extended flowering period — typically lasting 3–4 weeks on individual trees — provides sustained resources during a critical time in the pollinator calendar when many native plants have not yet reached peak bloom.

Ecosystem Role

As one of the tallest and most impressive trees in eastern North American forests, Tulip Tree plays a fundamental role in forest structure and ecosystem function that extends far beyond its value to individual species. Its massive canopy helps define the forest’s upper story, creating the vertical stratification that characterizes mature deciduous forests and supports diverse communities at different levels from the forest floor to the upper canopy.

The tree’s rapid growth rate and ability to quickly reach impressive heights makes it a pioneer species in forest succession, capable of rapidly colonizing forest gaps created by natural disturbances and helping to maintain continuous forest cover. This gap-filling ability is crucial for preventing soil erosion, maintaining watershed integrity, and ensuring that forest habitats remain connected across the landscape. The extensive root system helps stabilize soil on slopes and improves water infiltration, reducing surface runoff and protecting water quality in forest streams and rivers.

The massive amount of leaf litter produced by mature Tulip Trees contributes substantially to soil organic matter and nutrient cycling throughout forest ecosystems. The large leaves decompose relatively quickly compared to those of oak or hickory species, releasing nutrients that benefit the entire forest plant community. This rapid decomposition also supports the soil invertebrate communities that form the base of forest food webs, including earthworms, springtails, and various beetle species that process organic matter and make nutrients available to plant roots.

Perhaps most importantly, Tulip Tree’s exceptional longevity — potentially living 200–300 years or more — makes it a long-term repository of carbon and a stable component of forest ecosystems across multiple centuries. Ancient Tulip Trees serve as living monuments to forest history and provide continuity of habitat through changing environmental conditions. These legacy trees often become the focal points around which entire forest communities develop, supporting specialized species that require the unique conditions found only around very large, old trees.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Tulip Tree occupies a unique and profound place in North American cultural history, serving simultaneously as a practical resource, a symbol of natural abundance, and a witness to the continent’s human story. From Indigenous peoples who recognized its exceptional qualities thousands of years ago to modern conservation efforts focused on preserving old-growth specimens, Tulip Tree has been intimately connected to human culture and society throughout its range.

The Cherokee nation referred to Tulip Tree as “oo-na-sti,” translating to “the canoe tree,” a name that reflects one of the most important traditional applications of this remarkable species. The tree’s combination of massive size, straight grain, and relatively soft wood made it ideal for creating large dugout canoes capable of carrying multiple people and substantial cargo loads. These canoes were essential for transportation along the region’s extensive river systems, enabling trade, travel, and cultural exchange across vast distances. The process of creating a dugout canoe was both practical and ceremonial, often involving controlled burning to hollow out the interior while carefully preserving the hull’s structural integrity.

Cherokee craftspeople developed sophisticated techniques for selecting and working with Tulip Tree wood, choosing trees with specific characteristics for different applications. The largest, straightest specimens were reserved for canoe construction, while smaller trees provided wood for household items, tools, and construction materials. The inner bark was prepared as medicine, typically brewed as a tea or processed into tinctures for treating various ailments including digestive problems, respiratory conditions, and general weakness. Cherokee healers considered Tulip Tree bark to be a powerful tonic that could strengthen the constitution and restore vitality.

Other Indigenous nations throughout the tree’s range developed their own traditions and uses for Tulip Tree. The Iroquois used the bark medicinally for heart conditions and as a general strengthening tonic, while various Algonquian-speaking peoples incorporated the tree into ceremonial practices and seasonal celebrations. The aromatic properties of the bark and wood were widely recognized — dried materials were often burned as incense in purification ceremonies and to repel insects during summer months. The timing of the spectacular flower display also served as a natural calendar, marking important seasonal transitions and agricultural activities.

European colonists quickly recognized Tulip Tree’s extraordinary timber potential, and it rapidly became one of the most sought-after woods in colonial America. The combination of the tree’s massive size, straight grain, workable texture, and availability in large quantities made it invaluable for construction in a rapidly expanding colonial society. Early settlers used Tulip Tree lumber for virtually every aspect of building construction, from house framing and flooring to siding, interior finishing, and furniture making. The wood’s dimensional stability and resistance to warping made it particularly prized for fine woodworking and cabinetry.

During the colonial period, Tulip Tree became central to the development of American shipbuilding industry. The wood’s combination of light weight, strength, and workability made it ideal for ship construction, particularly for interior components, masts, and specialized fittings. Many of the ships that carried colonists to America and transported goods between the colonies and Europe incorporated significant amounts of Tulip Tree lumber. The species’ abundance and large size meant that shipbuilders could obtain the massive timbers needed for large vessels, contributing to America’s emergence as a maritime power.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw Tulip Tree become increasingly important to America’s expanding timber industry. The species was extensively logged throughout its range, with the largest and finest specimens commanding premium prices for specialized applications including architectural timbers, high-quality furniture, and millwork. The wood’s ability to accept paint and stain uniformly made it valuable for interior finishing work, while its workability with hand tools made it a favorite among craftspeople and furniture makers. Many historic American buildings, including some dating to the colonial period, showcase extensive use of Tulip Tree lumber in their construction.

Beyond its practical applications, Tulip Tree became a powerful symbol of American natural abundance and uniqueness. Early naturalists and botanists, including John Bartram and André Michaux, wrote extensively about the species in their explorations of American flora. The tree’s distinctive flowers and leaves made it a popular subject for botanical illustrations and natural history artwork, while its impressive size became a symbol of the continent’s natural grandeur. Thomas Jefferson, an enthusiastic naturalist and gardener, planted Tulip Trees at Monticello and corresponded about the species with other prominent figures of the era.

The Industrial Revolution brought new uses for Tulip Tree wood, including its adoption for interior components of railroad cars, factory flooring, and various manufactured products. The development of steam-powered sawmills allowed for more efficient processing of the large logs, while expanding transportation networks made it possible to ship Tulip Tree lumber to markets far from the forests where it grew. However, this period also saw the beginning of concerns about over-harvesting, as the largest and most accessible trees began to disappear from many areas.

In the 20th century, Tulip Tree continued to be commercially important for lumber, veneer, and pulpwood production, though the era of vast old-growth specimens largely came to an end due to extensive logging. The wood found new applications in plywood manufacturing, paper production, and engineered lumber products that could utilize smaller trees than traditional sawmill operations. The development of forest management practices and tree plantation systems helped ensure continued availability of Tulip Tree timber while attempting to address the sustainability concerns that had emerged during the previous century.

Contemporary interest in Tulip Tree has expanded far beyond timber to encompass its critical ecological roles and environmental benefits. Climate change research has identified the species’ rapid growth and large mature size as valuable for carbon sequestration projects, while restoration ecologists recognize its importance in re-establishing diverse forest ecosystems. Urban planners and landscape architects have gained new appreciation for the species as a native alternative to non-native shade trees, though its large mature size limits its application to appropriate large-scale settings.

Modern conservation efforts have focused on protecting remaining old-growth Tulip Tree specimens and the unique forest communities they support. These ancient trees, some of which may be 300+ years old, serve as living links to pre-colonial forest conditions and provide irreplaceable habitat for specialized species. Educational and interpretation programs often feature these remarkable trees as examples of what eastern American forests looked like before European settlement, helping visitors understand the profound changes that have occurred in forest ecosystems over the past several centuries.

Frequently Asked Questions

How fast does Tulip Tree grow, and how long does it take to mature?

Tulip Tree is one of the fastest-growing native hardwood trees in North America, typically adding 2–3 feet in height per year under optimal conditions of full sun, rich soil, and adequate moisture. Young trees in ideal conditions may grow even faster, sometimes reaching 4+ feet per year during their peak growth period. Under these conditions, a Tulip Tree can reach 40–50 feet in height within 15–20 years and approach its mature height of 70–90 feet within 30–40 years. However, the tree continues growing and developing for many decades, with some specimens living 200–300 years and reaching truly massive proportions over time.

When do Tulip Trees start flowering, and are the flowers visible from the ground?

Tulip Trees typically begin producing flowers when they reach about 15–20 years of age and 30–40 feet in height, though this can vary depending on growing conditions. The spectacular tulip-shaped flowers are quite large and beautiful, but they unfortunately often bloom high in the canopy where they can be difficult to see from ground level without binoculars. Younger trees and lower branches of mature trees may produce flowers at more visible heights. The best flower viewing is usually possible in late spring (May-June) when the blooms first open, before the leaves fully expand to obscure them.

Is Tulip Tree appropriate for residential properties, and what are the space requirements?

Tulip Tree is generally not suitable for typical residential properties due to its massive mature size of 70–90 feet tall with a spread of 35–50 feet. The tree also develops an extensive root system that can interfere with foundations, sidewalks, utilities, and nearby structures. Additionally, mature trees drop considerable quantities of flowers, seed pods, and large leaves that create maintenance challenges. Tulip Tree is best reserved for large properties (2+ acres), parks, public spaces, and rural settings where its size can be accommodated without creating problems for buildings or infrastructure.

What growing conditions does Tulip Tree require for optimal performance?

Tulip Tree requires full sun exposure (at least 6–8 hours of direct sunlight daily) and rich, deep, well-drained soil with consistent moisture throughout the growing season. The ideal soil is loamy with good organic content and a slightly acidic to neutral pH (6.0–7.0). The tree performs best in locations that mimic its natural forest habitat — rich coves and valleys with fertile, moist soils. While established trees show some drought tolerance, consistent moderate moisture is essential for optimal growth and health. Protection from strong winds is beneficial since the wood can be somewhat brittle.

Are there any significant problems or drawbacks with Tulip Trees?

The primary drawbacks of Tulip Tree are related to its size and the seasonal litter it produces. The large flowers create substantial debris in late spring, the distinctive leaves require considerable cleanup in fall, and the seed cones can create mess when they drop. Some people may be sensitive to the tree’s pollen. The wood is somewhat brittle compared to oak or other hardwoods, making mature trees potentially susceptible to branch breakage during ice storms or severe winds. The tree’s large size also limits where it can be appropriately planted without eventually creating conflicts with buildings or infrastructure.

Can Tulip Tree be grown from seed, and is it difficult to establish?

Yes, Tulip Tree can be successfully grown from seed, though it requires patience and proper handling. Collect the winged seeds in fall after they turn brown but before they disperse naturally. The seeds require cold stratification over winter (3–4 months at 32–40°F in moist peat or sand) to break dormancy. Plant stratified seeds in spring in well-prepared seedbeds or containers. Seedlings grow relatively slowly for the first 2–3 years as they develop extensive root systems, then growth accelerates dramatically. However, seed-grown trees may take 15–20 years to begin flowering, so purchasing nursery-grown specimens is often more practical for landscape applications where quicker results are desired.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Tulip Tree?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina