New York Ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis)

Vernonia noveboracensis, commonly known as New York Ironweed, is a robust herbaceous perennial that brings dramatic late-season color to wetlands, meadows, and naturalized gardens across the eastern United States. This member of the Asteraceae (sunflower) family is renowned for its intensely colored reddish-purple flower heads that bloom from late summer into fall, creating spectacular displays when planted in masses.

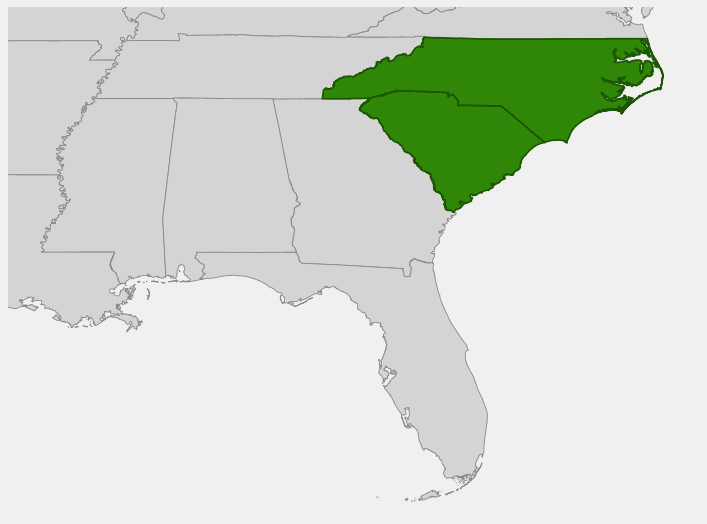

Despite its common name suggesting an association with New York, this species has a much broader native range extending from southern New England south to Georgia and west to the Great Plains. In the southeastern states, including North Carolina and South Carolina, it thrives in wet meadows, marsh edges, ditches, and low-lying areas where it forms impressive colonies of tall, leafy stems topped with vibrant purple flowers.

New York Ironweed is a cornerstone species for late-season pollinator support, blooming at a critical time when many other native wildflowers have finished their display. Its nectar-rich flowers attract a diverse array of butterflies, bees, and beneficial insects, while the seeds provide food for birds well into winter. The plant’s ability to thrive in challenging wet sites, combined with its stunning visual impact and exceptional wildlife value, makes it an outstanding choice for rain gardens, wet meadow plantings, and naturalized areas throughout its range.

Identification

New York Ironweed is a tall, robust perennial that typically grows 3 to 8 feet tall, occasionally reaching up to 10 feet in ideal conditions. The plant forms clumps from rhizomes and develops multiple sturdy, unbranched stems that become increasingly branched toward the top where the flower clusters develop. The overall growth habit is upright and architectural, making it a striking presence in the landscape.

Stems

The stems are stout, erect, and typically unbranched in their lower portions, becoming much-branched toward the top. They are green to purplish-green and may be slightly ridged or grooved. The stems are generally smooth but may have fine hairs, particularly in the upper portions near the flower heads.

Leaves

The leaves are alternate, lanceolate to narrowly elliptical, and typically 4 to 10 inches long and 1 to 3 inches wide. They have serrated margins and are dark green above, often with a slightly paler underside. The leaves are sessile or have very short petioles and are arranged spirally along the stem. The leaf surfaces may be smooth or have fine hairs, and the prominent veination gives them a somewhat textured appearance.

Flowers

The flowers are the plant’s most distinctive feature — small, tubular disc flowers arranged in dense, rounded heads about ½ to ¾ inch across. Each flower head contains 20 to 30 individual flowers, and the heads are clustered together in large, flat-topped or slightly domed terminal clusters (corymbs) that can be 4 to 6 inches across. The color is a distinctive reddish-purple to deep magenta that is unlike most other native wildflowers. Blooming occurs from late July through September, with peak bloom typically in August.

Seeds

The seeds (technically achenes) are small, dark brown, and topped with a bristly white pappus similar to dandelion seeds, allowing them to be dispersed by wind. The seed heads are attractive in their own right and can be left standing through winter for wildlife value and visual interest.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Vernonia noveboracensis |

| Family | Asteraceae (Sunflower) |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous Perennial |

| Mature Height | 4–7 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Bloom Time | July – September |

| Flower Color | Reddish-purple, magenta |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 5–9 |

Native Range

New York Ironweed has a native range that extends across much of the eastern United States, from southern New England south to northern Florida and west to the eastern Great Plains. However, the species shows considerable variation across this range, with different populations adapted to local conditions and displaying subtle differences in morphology and habitat preferences.

In the southeastern United States, particularly in North Carolina and South Carolina, New York Ironweed is most commonly found in the Coastal Plain and lower Piedmont regions, where it inhabits wet meadows, marsh edges, roadside ditches, and low-lying areas that remain moist throughout the growing season. These southern populations often grow in association with other wetland and wet meadow species such as Joe Pye Weed, Swamp Milkweed, and various native sedges and grasses.

The species demonstrates a strong preference for areas with consistent moisture, particularly during the growing season, though it can tolerate brief periods of flooding as well as moderate drought once established. It’s commonly found in areas that experience seasonal flooding or remain saturated during spring and early summer, then may dry out somewhat during late summer and fall.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring New York Ironweed: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

New York Ironweed is an excellent choice for challenging wet sites where many other ornamental plants struggle. Once established, it’s remarkably low-maintenance and provides spectacular late-season color and wildlife habitat.

Light

This species performs best in full sun, where it develops the most robust stems, abundant flowering, and intense flower color. While it can tolerate partial shade, plants grown in shaded conditions tend to be taller and leggier, may require staking, and produce fewer flowers. For the best display, choose a site that receives at least 6 hours of direct sunlight daily.

Soil & Water

New York Ironweed thrives in moist to wet soils and is an excellent choice for areas with poor drainage or seasonal flooding. It adapts to a wide range of soil types, from sandy to clay, but performs best in fertile, organic-rich soils. The plant requires consistent moisture during the growing season but can tolerate brief periods of drought once well-established. It’s particularly well-suited to rain gardens, bioswales, and areas that receive runoff from roofs or paved surfaces.

Planting Tips

Plant in spring after the last frost date. New York Ironweed can be started from seed sown directly in fall or spring, or from nursery-grown plants. Space plants 2–3 feet apart for mass plantings, or allow more room for individual specimens. The plant spreads slowly by rhizomes, so initial spacing will eventually fill in naturally. When planting in very wet areas, no soil amendment is usually necessary, but in average garden soils, adding compost can help retain moisture.

Pruning & Maintenance

Cut back stems in late fall or early spring before new growth begins. For shorter plants and bushier growth, stems can be cut back by half in early June, though this may delay flowering by 2–3 weeks. The plant may self-seed readily in favorable conditions, and seedlings can be transplanted or allowed to naturalize. Deadheading spent flowers will prevent self-seeding but removes the seed heads that provide food for birds.

Landscape Uses

New York Ironweed excels in several challenging landscape situations:

- Rain gardens and bioswales for stormwater management

- Wet meadow plantings and naturalized wetland edges

- Late-season pollinator gardens — critical nectar source in fall

- Cut flower gardens — excellent for arrangements

- Prairie and meadow restorations

- Pond and stream margins for erosion control

- Roadside plantings in wet ditches and swales

Wildlife & Ecological Value

New York Ironweed is exceptional for wildlife support, particularly as a late-season nectar source when many other flowers have finished blooming. Its value extends throughout the seasons and supports multiple trophic levels.

For Birds

The seeds are consumed by numerous bird species, including American Goldfinch, Indigo Bunting, Eastern Bluebird, and various sparrows and finches. The sturdy stems provide perching sites for birds hunting insects, and the seed heads can be left standing through winter to continue providing food. Migrating birds particularly benefit from both the seeds and the insects attracted to the flowers during fall migration periods.

For Mammals

Small mammals occasionally browse the foliage, though it’s not a preferred food source. The dense growth habit provides cover for small mammals, and the extensive root system creates habitat for various soil-dwelling creatures. White-tailed deer may browse young plants but generally leave mature stands alone.

For Pollinators

This is where New York Ironweed truly shines. The flowers attract an enormous variety of pollinators, including monarch butterflies (critical for their fall migration), skippers, fritillaries, and numerous native bees. Bumblebees are particularly common visitors, along with carpenter bees, sweat bees, and various beneficial wasps. The nectar is high-quality and available at a time when many other nectar sources have finished blooming, making it crucial for late-season pollinator survival and monarch butterfly migration fueling.

Ecosystem Role

As a dominant late-season blooming species, New York Ironweed plays a critical role in maintaining pollinator populations through the fall months. Its extensive root system helps stabilize soil in wet areas and contributes to nutrient cycling. The plant often serves as a nurse species, providing shelter and modified microclimate conditions that allow other wetland plants to establish. Its ability to colonize disturbed wet areas makes it valuable for natural wetland restoration and erosion control.

Cultural & Historical Uses

New York Ironweed has a rich history of traditional use by Indigenous peoples throughout its range. Various Native American tribes utilized different parts of the plant for medicinal purposes, though practices varied significantly by region. The Cherokee and other southeastern tribes used preparations of the roots and leaves to treat various ailments, including digestive issues and as a general tonic. The bitter taste of the plant was often mentioned in traditional accounts, and preparations typically required careful processing to make them palatable.

The common name “ironweed” refers to the plant’s tough, fibrous stems that were difficult to cut with early farming implements. European settlers found that the plants could withstand mowing and would quickly regrow, making them somewhat troublesome in agricultural areas but valuable for erosion control and wildlife habitat in areas not suitable for farming.

In traditional folk medicine, various ironweed species were sometimes used as substitutes for each other, with New York Ironweed being employed similarly to other members of the genus. However, it’s important to note that these plants contain compounds that can be toxic if consumed in large quantities, and traditional medicinal uses should not be attempted without proper knowledge and preparation.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, New York Ironweed was sometimes viewed as a weed in agricultural contexts, but its value for wildlife and soil stabilization in wet areas gradually became more recognized. By the late 20th century, the species gained appreciation in the native plant gardening movement, particularly for its exceptional value to pollinators and its striking ornamental qualities.

Modern research has focused on the plant’s ecological value, particularly its role in supporting monarch butterfly populations during their critical fall migration. Studies have shown that ironweeds, including New York Ironweed, are among the most important late-season nectar sources for monarchs, providing the energy they need for their long journey to overwintering sites in Mexico.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is New York Ironweed really native to New York?

Yes, despite some regional variation in distribution data, the species is native to New York and much of the eastern United States. The common name likely comes from early botanical collections made in New York. Local populations may show some variation, and regional ecotypes are adapted to local conditions.

Will this plant take over my garden?

New York Ironweed spreads slowly by rhizomes and may self-seed in favorable conditions, but it’s not aggressively invasive. It forms colonies gradually and can be controlled by removing unwanted plants. The spreading tendency is actually beneficial for creating naturalistic plantings and filling in wet areas.

Can I grow this in a regular garden bed?

While New York Ironweed prefers consistently moist conditions, it can adapt to average garden soil if provided with supplemental watering during dry spells. However, it performs much better in naturally moist or wet sites and may struggle in well-drained, dry locations.

When should I cut back the plants?

Leave the stems standing through winter to provide seeds for birds and overwintering habitat for beneficial insects. Cut back in late winter or early spring before new growth begins. If you want shorter plants, you can cut stems back by half in early June, but this will delay flowering.

How important is this plant for monarch butterflies?

New York Ironweed is extremely important for monarchs, particularly during their fall migration. Research has shown it’s one of the most valuable late-season nectar sources, providing the high-energy fuel monarchs need for their journey to Mexico. Planting ironweeds is one of the best ways to support monarch conservation.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries New York Ironweed?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina