Downy Serviceberry (Amelanchier arborea)

Amelanchier arborea (Michx. f.) Fernald, commonly known as Downy Serviceberry, Common Serviceberry, or Juneberry, is one of North America’s most beloved native small trees, earning its place in both natural ecosystems and cultivated landscapes through its spectacular seasonal displays and exceptional wildlife value. This member of the Rosaceae (rose) family transforms throughout the year: delicate white flowers herald spring’s arrival, sweet purple-black berries ripen in early summer, and brilliant yellow, orange, and red foliage creates one of the most stunning fall color displays among native trees.

Growing naturally from the Maritime Provinces of Canada south to northern Florida and west to Minnesota and eastern Texas, Downy Serviceberry thrives in diverse habitats from rocky slopes and forest edges to stream banks and woodland clearings. Its adaptability to various light conditions—from full shade to full sun—combined with moderate water needs makes it an exceptionally versatile choice for native plant gardens, restoration projects, and sustainable landscaping throughout much of eastern North America.

The common name “serviceberry” derives from early settlers’ practice of holding religious services in spring when these trees burst into bloom, creating white clouds of flowers across the landscape. “Juneberry” refers to the timing of fruit ripening, though the berries actually mature from late May through July depending on location and climate. Indigenous peoples have long valued serviceberries for food, with the nutritious fruits traditionally dried for winter use or mixed with meat and fat to create pemmican—highlighting this tree’s historical importance as both an ecological and cultural keystone species.

Identification

Downy Serviceberry typically grows as a small understory tree or large shrub, reaching 15 to 30 feet (4.5–9 m) tall with a trunk diameter of 4 to 8 inches (10–20 cm). The growth form is often multi-stemmed from the base, creating an attractive, naturalistic appearance that works well in both formal and informal landscape settings. Young trees have a distinctly upright, oval crown that becomes more rounded and spreading with age.

Bark

The bark is smooth and gray on young trees, becoming furrowed into narrow ridges on mature specimens. One of the most distinctive features of Downy Serviceberry is the way sunlight filters through the smooth gray bark, creating an attractive mottled pattern. The inner bark is reddish-brown when scratched, and the bark has a slightly bitter taste—though it lacks the medicinal properties of some related species.

Leaves

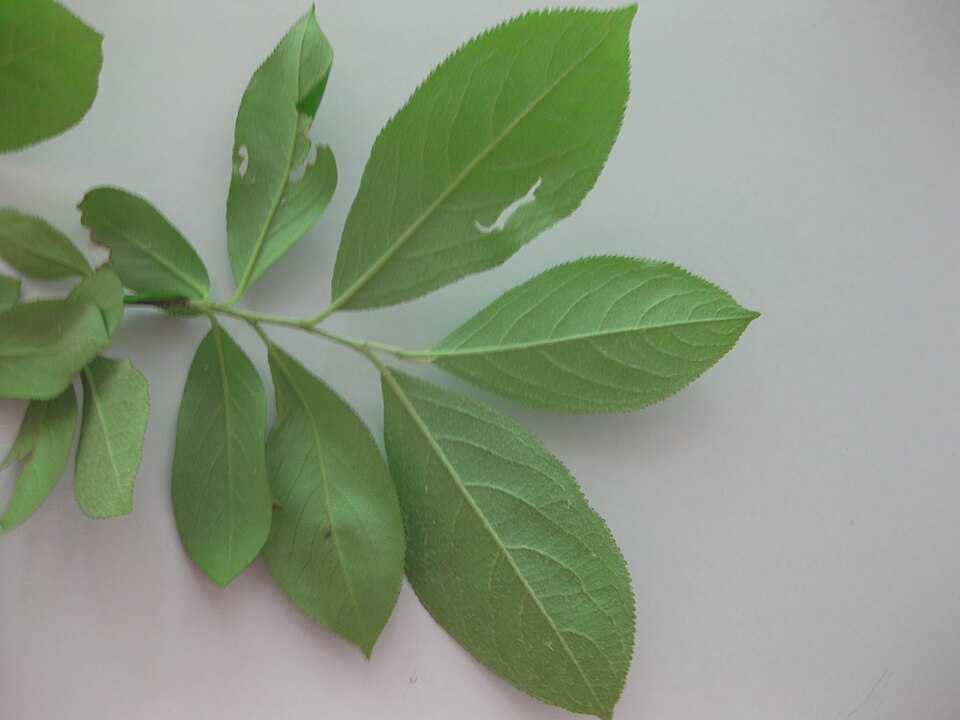

The leaves are simple, alternate, and oval to elliptic, measuring 2 to 4 inches (5–10 cm) long and 1 to 2 inches (2.5–5 cm) wide. They emerge with a distinctive downy, white pubescence—particularly noticeable on the underside—which gives the species its common name “Downy” Serviceberry. This fuzzy covering gradually diminishes as the leaves mature, though some hairiness usually persists along the midrib and main veins. Leaf margins are finely serrated with sharp teeth, and the prominent parallel veins create a distinctly ribbed texture. The fall color is exceptional, ranging from bright yellow through orange to deep red, often with multiple colors appearing on the same tree.

Flowers & Fruit

The flowers appear in early spring before the leaves are fully expanded, creating one of the most spectacular native flowering displays. Each flower is about ¾ inch (2 cm) across with five pure white, strap-shaped petals and numerous stamens with pink or red anthers. The flowers are arranged in drooping racemes (clusters) of 6 to 12 blooms, covering the tree in a cloud of white that can be visible from considerable distances.

The fruit is a pome (similar to an apple) that ripens from red to dark purple or nearly black in early to mid-summer. Each berry is about ⅜ inch (1 cm) in diameter with a sweet, mild flavor reminiscent of blueberries but with a subtle almond undertone. The berries are edible raw and highly prized by both wildlife and humans for their nutritional value and pleasant taste. Inside each fruit are small, soft seeds that are easily digestible and help with seed dispersal by birds and mammals.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Amelanchier arborea |

| Family | Rosaceae (Rose) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree / Large Shrub |

| Mature Height | 15–30 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Shade to Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | March – May |

| Flower Color | White |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

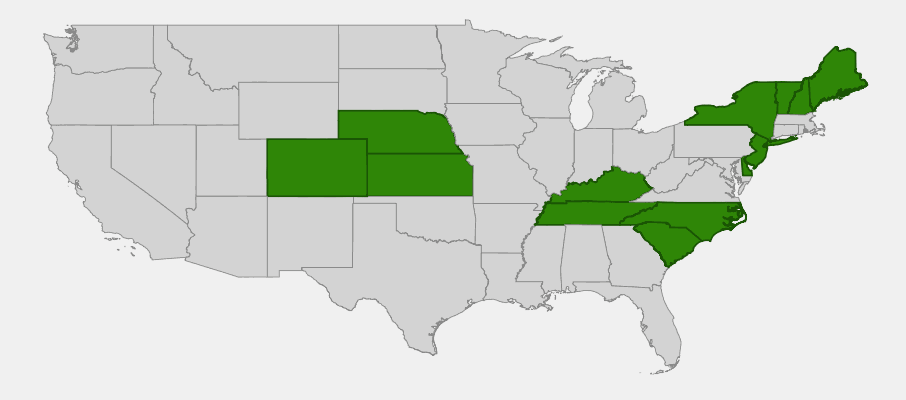

Native Range

Downy Serviceberry has one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American serviceberry species, stretching from southeastern Canada south to northern Florida and west to Minnesota, Kansas, and eastern Colorado. This remarkable distribution reflects the species’ adaptability to diverse climatic conditions, from the harsh winters of northern New England and the Maritime Provinces to the humid subtropics of the southeastern coastal plain.

Throughout its range, Downy Serviceberry typically occurs in mixed deciduous and deciduous-coniferous forests, showing a preference for forest edges, clearings, and areas with moderate disturbance. It is commonly found on rocky slopes, ridge tops, and well-drained upland sites, but also thrives in moister locations along stream banks and in rich coves. The species is particularly abundant in the Appalachian Mountains, where it forms an important component of oak-hickory and mixed mesophytic forest communities.

In the Great Lakes region, Downy Serviceberry is a characteristic species of the transition zone between northern coniferous forests and temperate deciduous forests, often growing alongside Sugar Maple, American Beech, and various oak species. Its ability to colonize disturbed areas and forest gaps makes it valuable for natural forest succession and ecosystem recovery following disturbances such as logging, fire, or severe weather events.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Downy Serviceberry: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Downy Serviceberry is among the most adaptable and low-maintenance native trees available to gardeners, combining exceptional ornamental value with remarkable tolerance for diverse growing conditions. Its natural adaptability makes it suitable for a wide range of landscape applications, from formal gardens to naturalized woodland areas.

Light

One of Downy Serviceberry’s greatest strengths is its exceptional tolerance for varying light conditions. In its native habitats, it thrives everywhere from deep forest shade to full sun exposures. In full sun, the tree develops a more compact, dense form with enhanced flowering and fruiting, plus more brilliant fall colors. In partial shade, it maintains good health while developing a slightly more open growth habit as it reaches toward available light. Even in fairly deep shade, Downy Serviceberry continues to grow and flower, though fruit production may be reduced.

Soil & Water

Downy Serviceberry prefers well-drained soils but is remarkably adaptable to various soil types, including clay, loam, and sandy soils. It naturally occurs on sites ranging from moist, rich bottomlands to dry, rocky ridgetops, demonstrating impressive drought tolerance once established. The ideal pH range is slightly acidic to neutral (5.5–7.0), but the tree tolerates both more acidic and alkaline conditions. Good drainage is more critical than soil fertility, as serviceberries can struggle in consistently waterlogged soils.

Planting Tips

Plant Downy Serviceberry in fall or early spring for best establishment. Choose a site that provides at least morning sun for optimal flowering and fruiting. Space trees 12–15 feet apart for screening purposes, or give individual specimens 20–25 feet of space to develop their natural form. Container-grown plants establish readily, but avoid disturbing the root ball excessively as serviceberries can be sensitive to root damage during transplanting.

Pruning & Maintenance

Minimal pruning is required for Downy Serviceberry. Remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter while the tree is dormant. If training to a single-trunk tree form, gradually remove lower shoots and suckers over several years. For multi-stemmed specimens, selective thinning of older stems every few years helps maintain vigor and flowering. Avoid heavy pruning, as serviceberries heal slowly from large cuts and may respond with excessive suckering.

Landscape Uses

Downy Serviceberry’s four-season interest and adaptability make it valuable in numerous landscape applications:

- Specimen planting — showcases spring flowers, summer fruit, and fall color

- Woodland gardens — naturalistic understory plantings

- Wildlife gardens — attracts birds, butterflies, and beneficial insects

- Native plant gardens — authentic regional flora

- Rain gardens — tolerates both moisture and periodic drought

- Slope stabilization — strong root system prevents erosion

- Urban landscapes — tolerates air pollution and compacted soils

- Food forests — edible fruit for humans and wildlife

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Downy Serviceberry is one of the most ecologically valuable native trees in eastern North America, supporting an extraordinary diversity of wildlife species while playing crucial roles in forest ecosystem function and succession.

For Birds

The berries of Downy Serviceberry are consumed by over 40 species of birds, making it one of the top native trees for avian nutrition. Major consumers include American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Northern Cardinals, Blue Jays, Baltimore Orioles, Scarlet Tanagers, and various thrush species. The early summer fruit ripening provides critical nutrition during the peak breeding and fledgling season when protein-rich insects alone may not meet all nutritional needs. The tree’s multi-stemmed growth form and dense branching also provide excellent nesting sites for songbirds.

For Mammals

Mammals ranging from chipmunks and squirrels to black bears and white-tailed deer utilize Downy Serviceberry extensively. Small mammals cache the nutritious fruits for winter consumption, while deer browse the twigs and foliage. Black bears are particularly fond of serviceberries and will often return to productive trees annually during fruit season. The tree’s suckering habit creates thickets that provide cover and nesting habitat for small mammals.

For Pollinators

The abundant early spring flowers provide crucial nectar and pollen when few other flowering plants are active. Native bees, including mason bees, sweat bees, and bumble bees, are primary pollinators, along with beneficial wasps, flies, and butterflies. The synchronized blooming with other early spring wildflowers creates important pollinator corridors in forest ecosystems.

Ecosystem Role

As a pioneer species, Downy Serviceberry plays vital roles in forest succession, colonizing disturbed areas and helping establish conditions for later successional species. Its nitrogen-fixing bacterial associates in the root zone improve soil fertility, while the annual leaf litter contributes organic matter that supports soil microbial communities. The tree’s ability to reproduce both by seed and root suckers allows it to form stabilizing colonies on erosion-prone sites.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Downy Serviceberry holds deep cultural significance throughout its native range, with Indigenous peoples having utilized this valuable tree for thousands of years. The Ojibwe called it misaskaatomin, while the Cherokee knew it as gaganvhi. These diverse linguistic traditions reflect the widespread importance of serviceberries as both food and medicine across numerous tribal nations.

The nutritious berries were traditionally harvested in early summer and either eaten fresh or dried in cakes for winter storage. Mixed with buffalo or venison and fat, dried serviceberries formed a key ingredient in pemmican—a high-energy travel food that could last for months. The bark was used medicinally by some tribes as a treatment for stomach ailments and as a wash for sore eyes, while the straight, strong wood was crafted into arrow shafts and tool handles.

European settlers quickly adopted serviceberries into their diet and discovered that the trees’ reliable spring blooming made them excellent indicators of seasonal timing. The saying “when serviceberries bloom, plant corn” guided agricultural timing across much of the eastern frontier. Early American botanists and naturalists, including John Bartram and Thomas Nuttall, documented the species’ importance in both natural ecosystems and human communities.

In modern times, Downy Serviceberry has gained recognition as an excellent native food crop, with cultivated varieties developed for improved fruit size and flavor. The berries are rich in antioxidants, vitamin C, and minerals, making them comparable to blueberries in nutritional value. They can be eaten fresh, made into jams and pies, or dried for later use. The tree’s ornamental value has also made it increasingly popular in sustainable landscaping and native plant gardening movements.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are serviceberries the same as Juneberries?

Yes, “serviceberry” and “Juneberry” are common names for the same genus (Amelanchier). The name “Juneberry” refers to the typical fruiting time, though berries may ripen from late May through July depending on location and weather. Other regional names include Shadblow, Shadbush, and Sarvis-tree.

Can you eat Downy Serviceberry fruit?

Absolutely! The berries are not only edible but delicious and nutritious. They have a sweet, mild flavor with subtle almond notes and can be eaten raw or used in baking. The berries are high in antioxidants, vitamin C, and minerals. Just be sure to leave plenty for the wildlife that depend on them.

How can I tell Downy Serviceberry apart from other serviceberry species?

The key identifying feature is the fuzzy, downy pubescence on the underside of young leaves, which gives this species its common name. Other serviceberries typically have smooth or only slightly hairy leaves. Downy Serviceberry also tends to be larger at maturity than most other native serviceberry species.

Does Downy Serviceberry have any pest or disease problems?

Downy Serviceberry is relatively pest and disease resistant but can occasionally be affected by fire blight, rust diseases, or aphids. Good air circulation, proper spacing, and avoiding excessive fertilization help prevent most problems. The tree’s natural resistance and ecological adaptability make it much more resilient than many non-native alternatives.

When is the best time to see Downy Serviceberry in bloom?

In North Carolina and South Carolina, Downy Serviceberry typically blooms from mid-March through April, depending on elevation and weather. The flowering usually occurs just before or as the leaves emerge, creating spectacular displays of white flowers against bare or newly leafing branches. Mountain populations bloom 2–4 weeks later than coastal areas.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Downy Serviceberry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina