Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis)

Sambucus canadensis, commonly known as Elderberry, American Elder, or Black Elderberry, is one of North America’s most valuable native shrubs, prized for both its stunning ornamental qualities and remarkable edible and medicinal properties. This fast-growing member of the Adoxaceae family forms graceful, multi-stemmed colonies that can reach 5 to 12 feet in height, creating dramatic seasonal displays from spring’s creamy flower clusters to autumn’s deep purple berry abundance and brilliant yellow foliage.

Found throughout much of North America from Canada to Mexico, Elderberry thrives in a wide range of habitats — from moist woodland edges and stream banks to prairie swales and disturbed areas. The plant’s adaptability, combined with its exceptional wildlife value and human uses, has made it a cornerstone species in both wild ecosystems and cultivated landscapes. In early summer, the shrubs become beacons of white as massive flat-topped flower clusters, sometimes measuring up to 10 inches across, cover the plants in fragrant blooms that attract countless pollinators.

For modern gardeners and land stewards, Elderberry represents the perfect combination of beauty, function, and ecological value. The flowers can be harvested for elderflower fritters, wines, and cordials, while the berries are prized for jams, jellies, wines, and immune-boosting syrups. Beyond its culinary applications, Elderberry provides critical habitat and food for over 120 species of birds and numerous mammals, while its rapid growth and dense root system make it excellent for erosion control and naturalized plantings.

Identification

Elderberry is a deciduous shrub that typically grows 5 to 12 feet tall and equally wide, though exceptional specimens can reach 20 feet. The plant forms dense colonies through underground rhizomes, creating thickets of multiple stems that provide excellent wildlife cover and visual impact in the landscape.

Stems & Bark

Young stems are green to reddish-brown and notably pithy — the hollow centers contain a soft, white pith that was historically used to make toy boats and blowguns. As stems mature, the bark becomes gray-brown and develops shallow furrows. The pith is a key identifying feature, distinguishing elderberry from other similar shrubs that have solid stems.

Leaves

The leaves are pinnately compound, typically composed of 5 to 7 (occasionally 9) leaflets arranged along a central rachis. Each leaflet is lance-shaped to oval, 2 to 6 inches long, with finely serrated edges and a pointed tip. The foliage is bright green during the growing season and turns brilliant yellow in fall before dropping, creating a spectacular autumn display. When crushed, the leaves emit a distinctive, somewhat unpleasant odor that helps distinguish elderberry from other plants.

Flowers

The flowers appear in late spring to early summer (May to July) in massive, flat-topped clusters called cymes that can measure 4 to 10 inches across. Individual flowers are tiny — about ¼ inch across — with 5 creamy-white petals, but the collective impact of hundreds of flowers per cluster is stunning. Each flower has 5 prominent yellow stamens that add to the visual appeal. The flowers are fragrant, with a sweet, honey-like scent that attracts numerous pollinators.

Fruit

The berries ripen from late summer into fall (August to October), transforming from green to deep purple or nearly black when fully mature. Each berry is about ¼ inch in diameter and grows in large, drooping clusters that can weigh down the branches. The berries contain 3 to 5 small seeds and have a tart, wine-like flavor when cooked (raw berries can cause stomach upset). The fruit clusters are often so abundant they create a dramatic purple display visible from considerable distances.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Sambucus canadensis |

| Family | Adoxaceae (Moschatel) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 5–12 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Bloom Time | May – July |

| Flower Color | Creamy White |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

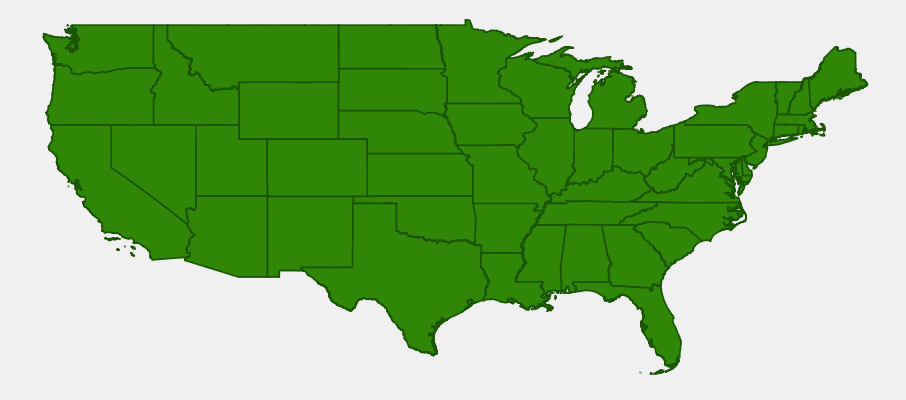

Native Range

Elderberry has one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American shrub, stretching from southeastern Canada south to Florida and Central America, and west from the Atlantic coast to the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. This remarkable distribution reflects the plant’s exceptional adaptability to diverse climates and growing conditions, from the humid forests of the Southeast to the prairie wetlands of the Midwest and the mountain valleys of the West.

In its natural habitat, Elderberry typically colonizes disturbed areas, forest openings, streambanks, marsh edges, and prairie swales — anywhere the soil remains consistently moist during the growing season. The species thrives in areas with periodic flooding or high water tables, making it particularly valuable for riparian restoration and rain garden applications. Its ability to quickly establish in disturbed soils has also made it important in post-agricultural succession and natural disaster recovery.

The plant’s wide-ranging adaptability has led to some taxonomic complexity, with botanists recognizing several subspecies and closely related species across different regions. What’s commonly called “American Elderberry” or “Black Elderberry” in cultivation may include Sambucus canadensis, S. cerulea, or S. racemosa depending on the specific region and botanical authority, but all share similar ecological roles and human uses.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Elderberry: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Elderberry is one of the most rewarding native shrubs to grow, offering rapid establishment, minimal maintenance requirements, and multiple seasons of interest. Its adaptability makes it suitable for a wide range of garden conditions and landscape applications.

Light

While Elderberry grows best in full sun, it readily tolerates partial shade and will still flower and fruit prolifically with 4-6 hours of direct sunlight daily. In full sun locations, plants develop more compact, dense growth with heavier flower and fruit production. In shadier conditions, plants may become more open and leggy but still provide excellent wildlife habitat and visual interest.

Soil & Water

Elderberry thrives in consistently moist, well-drained soil with high organic matter content. The plant tolerates a wide pH range (5.0-8.0) but performs best in slightly acidic to neutral conditions (6.0-7.0). While drought-tolerant once established, Elderberry produces the best growth, flowering, and fruiting with regular moisture. It’s particularly well-suited to rain gardens, bioswales, and areas with seasonal flooding, as it can tolerate standing water for short periods.

Planting Tips

Plant in spring or fall when temperatures are moderate and rainfall is typically more reliable. Space plants 6-10 feet apart for naturalized plantings, or 4-6 feet apart for more formal hedges or screens. Elderberry transplants easily from container stock and establishes quickly. Work plenty of compost into the planting area, and maintain consistent moisture during the first growing season to encourage rapid root establishment.

Pruning & Maintenance

Elderberry benefits from annual pruning in late winter or early spring before new growth begins. Remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches, and thin older canes to encourage new growth from the base. For fruit production, maintain 6-8 of the healthiest, most vigorous canes. Hard pruning every few years can rejuvenate older plants and increase fruit production. The plant’s rapid growth rate means pruning mistakes are quickly corrected.

Landscape Uses

Elderberry’s versatility makes it valuable in numerous landscape applications:

- Rain gardens — excellent for managing stormwater runoff

- Riparian buffers — stabilizes streambanks and filters runoff

- Wildlife gardens — provides food and habitat for diverse species

- Edible landscapes — flowers and berries offer culinary opportunities

- Privacy screens — creates effective seasonal screening

- Naturalized areas — perfect for low-maintenance, wild-looking plantings

- Pollinator gardens — massive flower displays support beneficial insects

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Few native plants match Elderberry’s extraordinary value to wildlife, supporting an impressive array of species throughout multiple seasons and providing both food and habitat across different ecosystem levels.

For Birds

Over 120 bird species consume elderberries, making this plant one of the most important wildlife food sources in North America. Major consumers include American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Northern Cardinals, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, Scarlet Tanagers, various woodpeckers, and countless species of warblers, vireos, and flycatchers. Game birds like Wild Turkeys, Ruffed Grouse, and various waterfowl also rely heavily on the berries. The dense, multi-stemmed growth provides excellent nesting habitat for smaller songbirds.

For Mammals

White-tailed deer, elk, and moose browse the foliage and young twigs, particularly during winter when other food sources are scarce. Black bears consume large quantities of berries in fall, helping to build fat reserves for winter hibernation. Smaller mammals including raccoons, opossums, squirrels, chipmunks, and various mice species also depend on the nutritious berries. The dense root systems and thicket-forming habit provide cover and denning sites for many small mammals.

For Pollinators

The massive flower displays attract an exceptional diversity of pollinators, including native bees, honeybees, butterflies, moths, beetles, and beneficial flies. The flat-topped flower clusters provide easy landing platforms for insects, while the abundant nectar and pollen support pollinator populations during the critical early summer period. Some butterfly species, including various fritillaries and skippers, use elderberry as a host plant for their caterpillars.

Ecosystem Role

Elderberry serves as a pioneer species in ecological succession, quickly colonizing disturbed areas and creating conditions favorable for other native plants. Its extensive root system prevents soil erosion, while the leaf litter enriches soil organic matter. The plant’s ability to fix nitrogen through associations with soil bacteria further enhances soil fertility for surrounding vegetation. In wetland edges and riparian areas, elderberry thickets create important transition zones between aquatic and terrestrial habitats.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Elderberry holds a remarkable place in human history, with evidence of its use spanning thousands of years across multiple continents. Native American peoples throughout the plant’s range developed sophisticated knowledge of elderberry’s medicinal, nutritional, and practical applications, traditions that were later adopted and adapted by European settlers.

Indigenous uses were extensive and varied by region. The Cherokee, Iroquois, and many other eastern tribes used elderberry bark, leaves, flowers, and berries in traditional medicine, treating everything from fevers and infections to pain and respiratory ailments. The pithy stems were hollowed out to make flutes, whistles, and blowguns for hunting small game. Berries were dried for winter food stores, and the flowers were used in ceremonial preparations. Many tribes considered the plant sacred, believing it offered protection against evil spirits.

European settlers quickly recognized elderberry’s value, integrating it into their own folk medicine traditions. By the 1800s, elderberry preparations were common in American pharmacies, and the plant was widely cultivated for both medicinal and culinary purposes. Elderflower water became a popular cosmetic, prized for its ability to soften skin and lighten freckles. The berries were essential for making preserves, wines, and cordials, particularly in rural areas where commercial preserves were unavailable.

In modern times, elderberry has experienced a remarkable renaissance in both commercial and home use. Scientific research has validated many traditional uses, particularly the berries’ high content of anthocyanins, vitamin C, and other antioxidant compounds. Commercial elderberry supplements, syrups, and extracts are now billion-dollar industries, while craft distilleries and home brewers prize elderflowers for their distinctive flavor in spirits and cordials. The growing interest in foraging, homesteading, and traditional foodways has brought elderberry back into mainstream American culture as both a garden plant and wild-harvested resource.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are elderberries safe to eat?

Ripe, cooked elderberries are generally safe and nutritious, but raw elderberries can cause stomach upset in some people. The bark, leaves, and seeds contain compounds that can be toxic if consumed in large quantities. Always cook elderberries before eating, and never consume any part of the plant except the ripe berries and flowers. When in doubt, consult reliable foraging guides or experienced herbalists.

How can I tell the difference between edible elderberry and toxic look-alikes?

True elderberry has compound leaves (5-7 leaflets), flat-topped white flower clusters, and distinctive pithy stems. Dangerous look-alikes include Water Hemlock (which has solid stems and different leaf patterns) and Pokeweed (which has simple leaves and upright berry clusters). Always verify identification using multiple reliable sources before harvesting any wild plant.

Will elderberry take over my garden?

Elderberry spreads moderately through underground rhizomes but is not typically considered invasive in garden settings. It forms colonies over time but spreads slowly enough to be manageable with occasional removal of unwanted shoots. The spreading habit actually makes it valuable for erosion control and naturalizing in larger landscapes.

Do I need multiple plants for fruit production?

While elderberry is self-fertile, you’ll get much better fruit production with multiple plants for cross-pollination. Plant at least two different cultivars or seedling plants for optimal berry yields. Even a single plant will produce some fruit, but multiple plants create more impressive displays and higher yields for harvest.

When should I harvest elderflowers and elderberries?

Harvest flowers in early morning when they’re fully open but still fresh, typically in late spring to early summer. Cut entire flower heads, leaving some for the plant and wildlife. Berries are ready in late summer to fall when they’re deep purple-black and easily separate from their stems. Always leave some berries for wildlife, and never harvest more than one-third of the available flowers or fruit from any single plant.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Elderberry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina