Wild Indigo (Baptisia tinctoria)

Baptisia tinctoria, commonly known as Wild Indigo, Yellow Wild Indigo, or Rattleweed, is a distinctive native legume of eastern North America that played a crucial role in early American history as a source of natural blue dye before true indigo became available. This member of the Fabaceae (pea or legume) family is a hardy, drought-tolerant perennial that forms dense, shrub-like clumps of blue-green foliage crowned with spikes of bright yellow flowers in midsummer, followed by distinctive black seed pods that rattle in the wind — hence one of its common names.

Growing naturally in dry, sandy soils of open woodlands, prairies, and abandoned fields, Wild Indigo is a medium-sized perennial reaching 2 to 3 feet tall and equally wide, with a deep taproot that allows it to thrive in challenging, drought-prone sites where many other plants struggle. The small, bright yellow pea-like flowers appear in terminal clusters during July and August, providing important nectar for native bees and butterflies during the peak summer season when many spring wildflowers have finished blooming.

What makes Wild Indigo particularly valuable in modern landscapes is its exceptional drought tolerance, nitrogen-fixing ability (like all legumes), and its role as a host plant for several specialist butterflies and moths. This tough native pioneer species is perfect for naturalized areas, prairie gardens, and challenging sites with poor, dry soil where its deep roots and drought adaptations allow it to flourish with minimal care while providing important ecological services.

Identification

Wild Indigo typically grows as a dense, rounded clump, reaching 2 to 3 feet tall and equally wide at maturity. The plant has a distinctly shrub-like appearance with numerous upright to slightly spreading stems arising from a deep, woody taproot system.

Stems

The stems are upright, branching, and smooth (glabrous), typically green to blue-green in color when young, becoming somewhat woody at the base with age. Unlike some Baptisia species, the stems of Wild Indigo are relatively slender and numerous, creating a dense, bushy appearance. The stems contain compounds that turn blue-black when exposed to air, which is the basis for the plant’s historical use as a dye source.

Leaves

The leaves are compound and palmate, consisting of three leaflets arranged in a clover-like pattern typical of many legumes. Each leaflet is obovate (egg-shaped with the broader end toward the tip), ½ to 1½ inches long, and blue-green to gray-green in color with a distinctive waxy or powdery appearance. The leaflets have smooth margins (entire) and are attached to the stem by short petioles. The blue-green foliage color and waxy texture help the plant conserve moisture in dry conditions.

Flowers

The flowers are small but numerous, arranged in terminal racemes (spike-like clusters) that rise above the foliage. Each individual flower is about ½ inch long and bright yellow in color, with the typical pea-flower structure: a banner petal, two wing petals, and a keel formed by two fused petals. The flower clusters are 2 to 6 inches long and appear at the tips of the branches. Blooming typically occurs from July through August, providing color during the peak summer season when many other native plants are not flowering.

Fruit & Seeds

The most distinctive feature after flowering is the seed pod (legume). The pods are oval to round, about ½ inch long, and turn from green to black as they mature. When fully mature and dry, the pods become papery and contain several small, hard seeds that rattle audibly when the plant is shaken by wind — hence the common name “Rattleweed.” The black pods persist on the plant well into winter, providing identification clues and adding textural interest to the winter landscape.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Baptisia tinctoria |

| Family | Fabaceae (Pea/Legume) |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous Perennial |

| Mature Height | 2–3 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | July – August |

| Flower Color | Bright yellow |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

Native Range

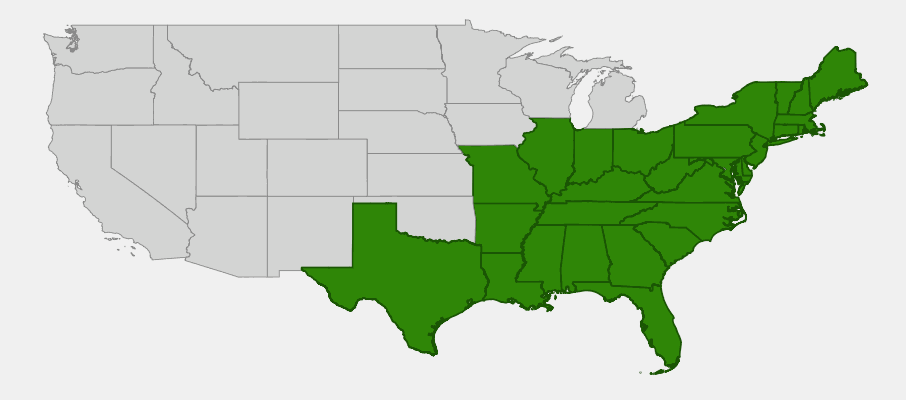

Wild Indigo has one of the broadest native ranges of any North American Baptisia species, extending from Maine and southern Canada west to Minnesota and south to northern Florida and eastern Texas. The species is particularly common in the Great Lakes region and throughout much of the eastern deciduous forest region, where it thrives in the transitional zones between forests and prairies.

In its natural habitat, Wild Indigo is found in a variety of open to partially shaded environments, including dry woodlands, woodland edges, old fields, prairies, and disturbed areas. It shows a particular affinity for sandy or rocky soils that are well-drained and often nutrient-poor. The plant is considered a pioneer species, often being among the first plants to colonize disturbed areas, abandoned agricultural fields, and other challenging sites where its deep taproot and nitrogen-fixing ability give it competitive advantages.

Historically, Wild Indigo was probably more common than it is today, particularly in areas that were regularly maintained by fire or other disturbances. The suppression of natural fire cycles and the intensive agriculture and development of much of its native range have reduced populations in many areas, though the plant remains locally common where suitable habitat exists.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Wild Indigo: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Wild Indigo is one of the most low-maintenance native plants available, thriving in challenging conditions that would stress many other perennials. Its deep taproot and nitrogen-fixing ability make it virtually self-sufficient once established.

Light

Wild Indigo performs best in full sun, where it develops its most compact, dense growth habit and flowers most prolifically. It can tolerate light shade but may become somewhat leggy and produce fewer flowers. In shadier conditions, the plant tends to stretch toward available light, potentially requiring staking or support.

Soil & Water

This native is remarkably adaptable to various soil types and conditions, thriving in everything from sandy soils to clay, as long as drainage is adequate. Wild Indigo actually prefers somewhat poor, well-drained soils and can struggle in rich, overly fertile conditions where it may produce excessive foliage at the expense of flowers. The plant is extremely drought tolerant once established, thanks to its deep taproot that can extend several feet into the soil. In fact, overwatering or overly rich soil can cause problems including root rot and decreased flowering.

Planting Tips

Plant Wild Indigo in spring or fall, giving it plenty of space to develop its full, rounded form. The plant develops a deep taproot and doesn’t transplant well once established, so choose the location carefully. Space plants 3-4 feet apart if planting in groups. Because of the deep taproot, container plants should be planted when relatively young, as older plants with established root systems may have difficulty adapting to transplanting.

Maintenance

Wild Indigo is virtually maintenance-free once established. The plant requires no fertilization — in fact, as a nitrogen-fixing legume, it actually improves soil fertility for surrounding plants. Deadheading spent flowers will prevent self-seeding if desired, but many gardeners prefer to leave the attractive black seed pods for winter interest and wildlife value. The plant may self-seed moderately in suitable conditions. Established clumps rarely need division and are best left undisturbed.

Landscape Uses

Wild Indigo’s toughness and distinctive appearance make it valuable in many challenging landscape situations:

- Prairie gardens — essential component of authentic prairie plantings

- Xeriscape gardens — excellent drought-tolerant specimen

- Naturalized areas — perfect for low-maintenance wildflower plantings

- Pollinator gardens — important nectar source and butterfly host plant

- Restoration projects — pioneer species for disturbed or degraded sites

- Wildlife gardens — supports specialist butterflies and beneficial insects

- Difficult sites — thrives where other plants struggle (poor soil, drought)

- Winter interest — black seed pods provide structure and texture

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Wild Indigo provides exceptional ecological value, serving as a host plant for several specialist butterflies and moths while also supporting a wide range of other wildlife species.

For Butterflies & Moths

Wild Indigo is the host plant for several specialist Lycaenidae (gossamer-winged) butterflies, including the Wild Indigo Duskywing (Erynnis baptisiae) and the Frosted Elfin (Callophrys irus). These butterflies depend entirely on Baptisia species for larval development, making Wild Indigo essential for their survival. The plant also hosts several moth species, including the Rattlebox Moth, whose caterpillars feed specifically on Baptisia foliage.

For Pollinators

The bright yellow flowers attract a wide variety of native bees, including bumblebees, carpenter bees, and various solitary bee species. The flowers provide both nectar and pollen during midsummer when many other sources may be scarce. Long-tongued bees are particularly effective pollinators due to the flower structure, though various other insects also visit the blooms.

For Birds

While birds don’t typically eat the hard seeds directly, the dense, shrub-like growth provides excellent cover for ground-nesting birds and small mammals. The persistent seed pods may provide some food for specialized seed-eating birds, and the plant’s tendency to attract insects makes it valuable for insectivorous birds feeding young during the breeding season.

Ecosystem Role

As a nitrogen-fixing legume, Wild Indigo plays a crucial role in soil improvement, particularly in nutrient-poor sites. The plant’s deep taproot helps break up compacted soils and brings nutrients from deep soil layers to the surface through leaf drop. Its role as a pioneer species makes it valuable for natural succession and restoration of disturbed areas. The plant also helps stabilize soil with its extensive root system, making it useful for erosion control on slopes and difficult sites.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Wild Indigo holds a significant place in American colonial history, serving as an important source of blue dye before true indigo (Indigofera tinctoria) became widely available. The common name “Wild Indigo” reflects this historical use, though the blue dye produced from this native plant was generally considered inferior to that from true indigo. The dyeing process involved fermenting the leaves and stems to release the blue compounds, a technique learned by European settlers from Indigenous peoples.

Various Eastern Woodland tribes, including the Cherokee, Choctaw, and other southeastern nations, had long used Wild Indigo for both medicinal and practical purposes. The roots were used in traditional medicine as a treatment for various ailments including fever, infections, and wounds, though these preparations required specific knowledge due to the plant’s potentially toxic compounds. The common name “Rattleweed” comes from the distinctive sound made by the mature seed pods, which some groups used as natural rattles or noisemakers.

During the colonial period, when trade disruptions made imported indigo expensive or unavailable, Wild Indigo became an important domestic source of blue dye for textiles. While the color was not as vibrant or long-lasting as true indigo, it provided an accessible alternative for frontier communities. The dye industry around Wild Indigo was never as extensive as the true indigo plantations of South Carolina and Georgia, but it served local and regional needs throughout much of the eastern United States.

In folk medicine, Wild Indigo continued to be used through the 19th and early 20th centuries, primarily as a treatment for infections, wounds, and fever. However, modern research has revealed that the plant contains potentially toxic alkaloids, and its medicinal use is no longer recommended without professional supervision. The plant’s historical medicinal applications should be considered primarily of historical interest rather than practical use.

Today, Wild Indigo is valued primarily for its ecological role and ornamental qualities rather than for any practical applications. The plant has gained renewed interest among native plant enthusiasts, prairie restoration specialists, and butterfly gardeners who recognize its importance as a host plant for endangered specialist butterflies and its role in supporting native pollinator communities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Wild Indigo toxic to humans and pets?

Yes, Wild Indigo contains potentially toxic alkaloids, particularly cytisine, which can cause gastrointestinal upset if ingested. While serious poisoning is rare, the plant should not be consumed, and pets and children should be kept away from the foliage and seeds. The toxicity is generally mild but can cause nausea, vomiting, and digestive issues.

Why won’t my Wild Indigo bloom?

Several factors can prevent flowering: insufficient sunlight (needs full sun), overly rich or fertilized soil (prefers poor to moderate fertility), excessive moisture (prefers drier conditions), or plant immaturity (may take 2-3 years to establish and bloom reliably). Young plants often focus energy on root development before flowering heavily.

Can I move an established Wild Indigo plant?

Moving established Wild Indigo is very difficult and often unsuccessful due to the deep taproot system. The plant is best left undisturbed once established. If moving is absolutely necessary, do it when the plant is very young (first year) and in early spring before growth begins, taking as much root as possible.

How do I propagate Wild Indigo?

Wild Indigo is easiest to grow from seed, which should be scarified (lightly scratched) and soaked overnight before planting. Seeds can be planted in fall for natural stratification or started indoors in spring. The plant may self-seed in favorable conditions. Division is generally not recommended due to the taproot structure.

What’s the difference between Wild Indigo and other Baptisia species?

Wild Indigo (B. tinctoria) is distinguished by its yellow flowers, smaller size (2-3 feet), and smaller leaflets compared to other common Baptisia species like Blue Wild Indigo (B. australis) or White Wild Indigo (B. alba). The black seed pods and blue-green foliage are also characteristic features.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Wild Indigo?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina