Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana)

Prunus virginiana, commonly known as Chokecherry, Bitter-berry, or Virginia Bird Cherry, is a hardy and adaptable native deciduous tree or large shrub that plays a vital ecological role across much of North America. This member of the Rosaceae (rose) family is easily recognized by its distinctive white flower clusters that bloom in spring, followed by dark red to purple-black cherries that provide crucial food for wildlife despite their astringent taste that gives the plant its common name. Found naturally from Alaska to Newfoundland and south through the western mountains and northern plains, Chokecherry demonstrates remarkable adaptability to diverse growing conditions and climates.

Growing typically as a small tree or large shrub reaching 30 to 50 feet tall, Chokecherry forms dense colonies through root sprouting, creating valuable wildlife thickets in its natural habitat. The tree’s most notable features include its profuse clusters of small white flowers that appear in late spring, simple oval leaves with finely serrated margins, and abundant clusters of dark cherries that ripen in late summer. While the fruit is barely palatable to humans due to its astringent quality, it serves as a crucial food source for over 40 species of birds and numerous mammals, making Chokecherry one of the most ecologically valuable native trees for wildlife support.

This versatile species thrives in a wide range of conditions from full sun to full shade and tolerates both moist and moderately dry soils, making it excellent for naturalistic plantings, wildlife gardens, and restoration projects. Its ability to grow in challenging sites, provide erosion control through extensive root systems, and support abundant wildlife makes Chokecherry particularly valuable for ecological restoration and large-scale native plantings. While not typically chosen for formal landscapes due to its suckering habit and somewhat irregular form, Chokecherry is indispensable in wildlife-focused gardens and natural areas where its ecological benefits far outweigh any aesthetic limitations.

Identification

Chokecherry typically grows as a small tree or large shrub, reaching 30 to 50 feet (9–15 m) tall, though it often remains smaller in harsh conditions. The growth form varies from a single-trunked small tree to a multi-stemmed large shrub, depending on growing conditions and management. In favorable conditions with adequate moisture and protection, it can develop into a well-formed small tree with a rounded crown, while in drier or more challenging sites it tends to remain shrubby and form dense colonies through root sprouting.

Bark

The bark is smooth and gray to brown on young trees and branches, becoming darker and developing shallow furrows with age. On older trunks, the bark may become somewhat scaly or fissured, but it never develops the deep furrows of many other trees. The bark on young twigs is smooth and often reddish-brown to gray, and may have prominent lenticels (breathing pores) that appear as light-colored horizontal marks.

Leaves

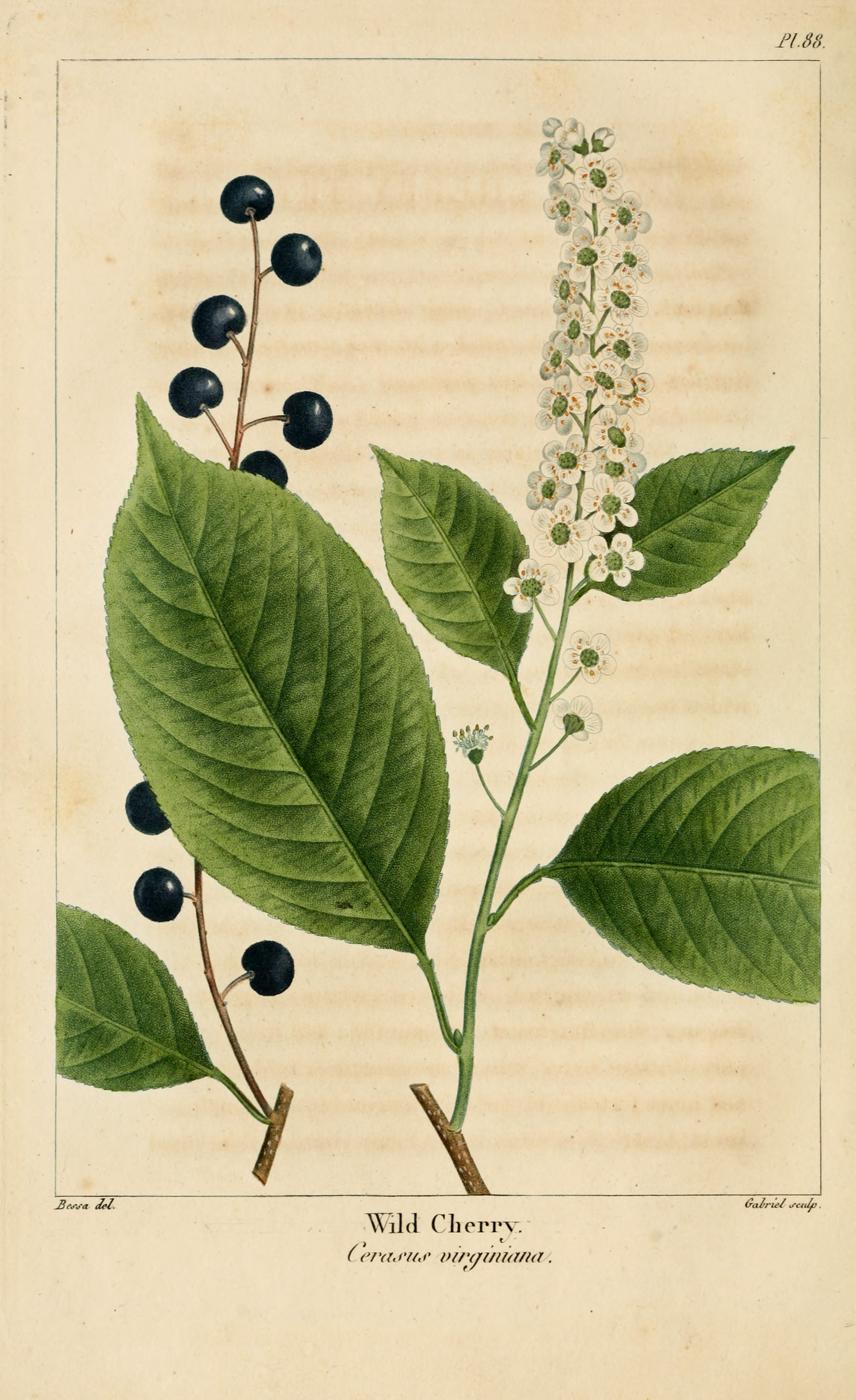

The leaves are simple, alternate, and oval to elliptical in shape, measuring 2 to 4 inches (5–10 cm) long and 1 to 2 inches (2.5–5 cm) wide. They have finely serrated margins with sharp, pointed teeth, and the tip of each leaf comes to a sharp point (acuminate). The upper surface is dark green and smooth, while the underside is paler and may have fine hairs along the midvein. The leaf stems (petioles) are usually short, about ¼ to ½ inch long. In fall, the leaves turn yellow to orange-red before dropping.

Flowers

The flowers are one of Chokecherry’s most distinctive and attractive features. They appear in dense, cylindrical clusters (racemes) 3 to 6 inches (7.5–15 cm) long at the ends of branches in late spring, typically after the leaves have emerged. Each individual flower is small, about ⅓ inch (8 mm) across, with five white petals surrounding numerous stamens that give the flower cluster a fuzzy appearance. The flowers have a sweet, somewhat almond-like fragrance and are highly attractive to bees and other pollinators.

Fruit

The fruit is a small drupe (stone fruit) about ¼ to ⅜ inch (6–10 mm) in diameter that hangs in dense clusters. The cherries ripen from red to dark purple or nearly black in late summer, typically July to September depending on location. Each fruit contains a single large seed (pit) and has astringent, puckering flesh that is technically edible but quite unpalatable when eaten raw due to high tannin content. The fruit is extremely important for wildlife, with the clusters often persisting into early winter and providing crucial food during migration and harsh weather periods.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Prunus virginiana |

| Family | Rosaceae (Rose) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree / Large Shrub |

| Mature Height | 30–50 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | May – June |

| Flower Color | White |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–7 |

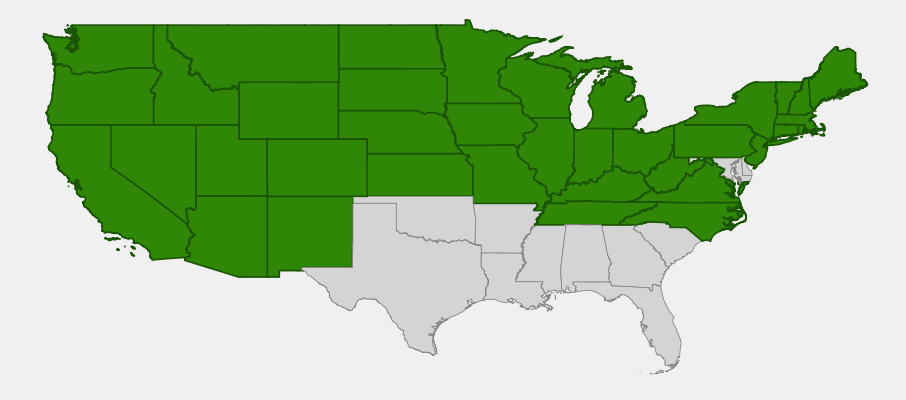

Native Range

Chokecherry has one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American tree, stretching from Alaska and northern Canada south through the western mountains to California and New Mexico, and across the northern Great Plains to the Great Lakes region and northeastern United States. This remarkable distribution reflects the species’ exceptional adaptability to diverse climatic conditions, from the harsh winters of Alaska and northern Canada to the hot, dry summers of the western mountains and plains.

In its natural habitat, Chokecherry is most commonly found along streams, in mountain valleys, on hillsides, and at forest edges where it receives adequate moisture but also good air circulation. The species shows remarkable elevation tolerance, growing from near sea level in northern regions to over 8,000 feet in the Rocky Mountains. It’s particularly common in aspen groves, mixed deciduous-coniferous forests, and riparian areas where it often forms dense thickets through root sprouting.

Throughout its vast range, Chokecherry serves as an important pioneer species, colonizing disturbed areas and creating habitat for other wildlife. The tree’s ability to thrive in both moist and moderately dry conditions, combined with its tolerance for a wide range of soil types and pH levels, has made it a valuable species for erosion control and habitat restoration projects. In many regions, Chokecherry represents one of the most reliable and productive wildlife food sources, supporting diverse bird and mammal populations across dramatically different ecosystems.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Chokecherry: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Chokecherry is one of the most adaptable and low-maintenance native trees for North American gardens. Its tolerance for diverse growing conditions, exceptional cold hardiness, and valuable wildlife benefits make it an excellent choice for naturalistic plantings, wildlife gardens, and areas where a more formal landscape tree might struggle.

Light

Chokecherry is remarkably adaptable to light conditions, growing successfully in everything from full sun to full shade. In full sun, plants develop a more compact, dense form with abundant flowering and fruiting, while in shade they tend to be more open and may produce fewer flowers. The species naturally occurs at forest edges and in clearings, so it’s well-adapted to varying light conditions throughout the day and seasons. This flexibility makes it valuable for challenging sites where other trees might not thrive.

Soil & Water

This adaptable tree grows in a wide variety of soil types, from rich, loamy soils to rocky, sandy, or clay conditions. Chokecherry prefers well-drained soils but tolerates both periodic flooding and drought conditions once established. It grows best with moderate moisture levels but can adapt to both wetter and drier conditions. The tree is tolerant of alkaline soils and salt, making it useful in challenging sites including roadside plantings and areas with poor soil conditions. pH tolerance ranges from acidic to quite alkaline (5.0–8.5).

Planting Tips

Plant Chokecherry in fall or early spring for best establishment. The tree can be grown from seed (which requires cold stratification), purchased as container stock, or in some cases moved as a small volunteer plant. Space trees 15–20 feet apart if planting multiple specimens, though closer spacing is fine for wildlife thickets. Choose the planting location carefully, as Chokecherry will spread through root suckers over time, potentially forming colonies. This spreading habit is beneficial in naturalistic settings but may not be desirable in formal landscapes.

Pruning & Maintenance

Chokecherry requires minimal pruning and maintenance once established. Remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter while the plant is dormant. If a more tree-like form is desired, gradually remove lower branches and select a single leader. Root suckers can be removed to control spread, or left to develop into a naturalistic thicket. The tree is generally free from serious pests and diseases, though it may occasionally be affected by tent caterpillars, aphids, or fungal leaf spots. These issues are rarely serious enough to warrant treatment in naturalistic settings.

Landscape Uses

Chokecherry’s adaptability and wildlife value make it suitable for many landscape applications:

- Wildlife gardens — provides food for over 40 bird species and numerous mammals

- Naturalistic plantings and restoration projects

- Erosion control — extensive root system stabilizes slopes and banks

- Windbreaks and shelterbelts, especially in harsh climates

- Difficult sites — tolerates poor soils, drought, and extreme temperatures

- Screening and privacy — dense growth provides effective visual barriers

- Pollinator support — abundant spring flowers attract bees and butterflies

- Four-season interest — flowers in spring, fruit in summer, fall color, winter form

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Chokecherry is one of the most important native trees for wildlife support, providing food, shelter, and nesting habitat for a remarkable diversity of species. Its abundant fruit production, dense growth form, and widespread adaptability make it a keystone species in many ecosystems across North America.

For Birds

Over 40 bird species are known to consume Chokecherry fruit, making it one of the most valuable native trees for avian wildlife. Regular consumers include American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Bohemian Waxwings, Evening Grosbeaks, Pine Grosbeaks, Various thrush species, Blue Jays, Gray Jays, Magpies, and numerous finch and sparrow species. Game birds such as Ruffed Grouse, Sharp-tailed Grouse, and Wild Turkeys also feed on both the fruit and buds. The dense, often multi-stemmed growth form provides excellent nesting habitat for many songbird species, while the early flowers attract insects that serve as crucial protein sources during the breeding season.

For Mammals

Many mammals depend on Chokecherry for food and habitat. Black bears consume large quantities of the fruit in late summer, often breaking branches to access the cherry clusters. Other mammals that regularly feed on Chokecherry include chipmunks, squirrels, mice, raccoons, and various small carnivores. Larger mammals such as deer, elk, and moose browse the twigs and leaves, particularly in winter when other food sources are scarce. The tree’s suckering habit creates dense thickets that provide crucial thermal cover and escape habitat for numerous small mammals and ground-dwelling birds.

For Pollinators

Chokecherry’s abundant spring flowers are highly attractive to a wide variety of pollinators. Native bees, including mason bees, leafcutter bees, and various solitary bee species, are frequent visitors, along with honeybees and bumblebees. The flowers also attract beneficial flies, beetles, and butterflies. The timing of Chokecherry blooming — typically late spring after many early flowers have finished but before summer flowers begin — makes it particularly valuable for filling gaps in pollinator food sources.

Ecosystem Role

Chokecherry plays crucial roles in ecosystem function and stability. As a pioneer species, it helps colonize disturbed areas and creates conditions for forest succession. Its extensive root system helps prevent soil erosion on slopes and streambanks, while its ability to fix nitrogen (through associations with certain soil bacteria) can improve soil fertility. The tree’s role in supporting such a large number of wildlife species makes it a keystone species in many ecosystems — its presence supports complex food webs and biodiversity that extend far beyond its direct interactions with other species.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Chokecherry holds profound cultural significance for many Indigenous peoples of North America, particularly among Great Plains and northern forest tribes who have used the tree for food, medicine, and materials for thousands of years. The Lakota, Dakota, Ojibwe, Cree, Blackfoot, and many other tribes considered Chokecherry one of their most important wild food sources. The fruit was typically harvested in late summer when fully ripe and processed in various ways to reduce its astringency and preserve it for winter consumption.

Traditional preparation methods included drying the whole cherries (including pits) and grinding them into a powder that was mixed with dried meat and fat to make pemmican — a high-energy, long-lasting travel food that was essential for hunting expeditions and winter survival. The ground cherry-pit mixture added important nutrients and gave pemmican its characteristic flavor. Some tribes also made “wojapi,” a traditional sauce or pudding from chokecherries that was eaten fresh or dried for later use.

Beyond nutrition, Chokecherry had extensive medicinal applications in Indigenous traditions. The inner bark was used to treat diarrhea, stomach problems, and respiratory ailments, while preparations from the roots were used for various women’s health concerns. Some tribes used Chokecherry bark tea to treat wounds and infections, and the plant was incorporated into ceremonial and spiritual practices. The flexible wood was used for making arrows, tool handles, and other implements where strength and flexibility were important.

European settlers and homesteaders adopted many Indigenous uses of Chokecherry and developed additional applications. The fruit was used to make jellies, syrups, and wine, though the high tannin content required careful processing. During the Great Depression and World War II, wild chokecherries became an important source of Vitamin C and other nutrients for rural families. The wood was used for fence posts, small tools, and fuel, while the tree’s hardiness made it valuable for windbreaks and erosion control on homesteads and farms.

Today, Chokecherry continues to be used in traditional and modern food preparations, particularly in areas with strong Indigenous cultural connections. Modern foragers prize the fruit for making unique jellies, syrups, and desserts, though proper processing is essential to achieve palatable results. The tree’s primary modern value, however, lies in its ecological benefits and its role in wildlife habitat and restoration projects across its vast native range.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are chokecherries poisonous?

Chokecherry fruit is safe to eat, though quite astringent and puckering when raw. However, the leaves, bark, and especially the pits contain cyanogenic compounds that can be toxic if consumed in large quantities. The pits are traditionally ground and processed with the fruit in Indigenous food preparations, which breaks down these compounds. Fresh leaves and bark should not be consumed, and livestock can be poisoned by browsing large quantities of fresh Chokecherry foliage.

How can I make chokecherries taste better?

Traditional methods include cooking the fruit into jellies, syrups, or sauces, often with added sugar to balance the astringency. Some people ferment chokecherries into wine. The key is processing the fruit while hot and straining out the pits and skins. Many modern recipes combine chokecherries with other fruits like apples or grapes to create more palatable preserves.

Will Chokecherry spread in my yard?

Yes, Chokecherry spreads through root suckers and can form colonies over time. This is beneficial in naturalistic settings where wildlife thickets are desired, but it may not be appropriate for formal landscapes. Root suckers can be removed to control spread, or you can plant Chokecherry in areas where its spreading habit is welcome.

Why isn’t my Chokecherry producing fruit?

Chokecherry trees may take 3–5 years to begin fruiting. Poor fruit production can be due to insufficient sunlight (shade reduces flowering), lack of pollinators, late frost damage to flowers, or drought stress during the growing season. Most Chokecherry trees are self-fertile, so you don’t need multiple trees for fruit production.

When should I harvest chokecherries?

Harvest chokecherries when they’re fully ripe and dark purple to black, typically in late summer (July–September depending on location). Ripe fruit should be soft to the touch and come off easily when touched. Unripe fruit is extremely astringent, while overripe fruit may be mushy and less flavorful.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Chokecherry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota