Prairie Larkspur (Delphinium virescens)

Delphinium virescens, commonly known as Prairie Larkspur, Plains Larkspur, or White Larkspur, is a graceful native perennial that brings vertical elegance and unique architectural form to prairie gardens and naturalized landscapes across the Great Plains and adjacent regions. This member of the Ranunculaceae (buttercup) family is distinguished by its tall, slender spikes of intricate white to pale blue flowers, each adorned with the characteristic spur that gives larkspurs their distinctive appearance and name.

Growing naturally in the challenging environment of the Great Plains, Prairie Larkspur has evolved remarkable adaptations for surviving in areas of extreme weather, variable precipitation, and intense prairie winds. The plant typically reaches 1 to 4 feet tall, forming clumps of deeply divided, palmate leaves that provide an attractive backdrop for the striking flower spikes that emerge from June through July. Unlike its cultivated garden cousins, Prairie Larkspur is supremely drought-tolerant and requires no supplemental watering once established, making it an ideal choice for xeriscaping and low-water gardens.

What makes Prairie Larkspur particularly valuable in ecological gardens is its role as a specialized pollinator plant. The complex flower structure, with its deep spurs and intricate architecture, is specifically adapted for long-tongued bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds. The plant serves as an important nectar source during the early summer period when many spring wildflowers have finished blooming but late-summer species have not yet begun. This timing makes Prairie Larkspur a critical bridge species for maintaining continuous pollinator resources throughout the growing season. Despite being a member of a genus known for toxicity, Prairie Larkspur plays an important ecological role and adds rare architectural beauty to native plant gardens, particularly those designed to celebrate the unique flora of America’s grasslands.

Identification

Prairie Larkspur is an herbaceous perennial that forms clumps from a deep taproot system, allowing it to access moisture far below the surface during drought periods. The plant typically reaches 1 to 4 feet in height, though exceptional specimens in favorable conditions may grow slightly taller. The overall form is upright and somewhat sparse, with most of the visual impact concentrated in the dramatic flower spikes that crown the plant in early summer.

Leaves

The leaves are deeply divided in a palmate pattern, resembling an open hand with 3 to 5 main segments that are further subdivided into narrow, linear lobes. This finely dissected foliage gives the plant a delicate, almost fern-like appearance that contrasts beautifully with the bold flower spikes. The leaves are alternate, ranging from 2 to 4 inches across, and are typically a blue-green to gray-green color that helps them reflect intense prairie sunlight. Lower leaves are larger and more divided, while upper leaves become progressively smaller and less complex as they approach the flower spike.

Flowers

The flowers are Prairie Larkspur’s most distinctive feature — arranged in tall, terminal racemes that can extend 6 to 18 inches above the foliage. Individual flowers are complex and irregular, typically ½ to ¾ inch across, with five sepals (not petals) that form the visible flower structure. The most distinctive feature is the prominent spur that extends backward from the uppermost sepal, giving the flower its characteristic larkspur shape. Flower color ranges from pure white to pale blue or lavender, often with subtle variations within a single spike. Each flower contains four small petals that are often inconspicuous, hidden within the sepals, and numerous stamens and pistils.

Seeds & Dispersal

After flowering, Prairie Larkspur produces distinctive follicles (dry fruits that split along one side) containing numerous small, dark seeds. The seeds are angular and roughly pyramid-shaped, about ⅛ inch long, with a wrinkled surface texture. They are primarily dispersed by wind and gravity, though some may be carried by animals or water. The plant typically produces abundant seed, ensuring its persistence in prairie ecosystems despite the challenges of drought and fire.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Delphinium virescens |

| Family | Ranunculaceae (Buttercup) |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous Perennial |

| Mature Height | 1–4 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate |

| Bloom Time | June – July |

| Flower Color | White to pale blue |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–8 |

Native Range

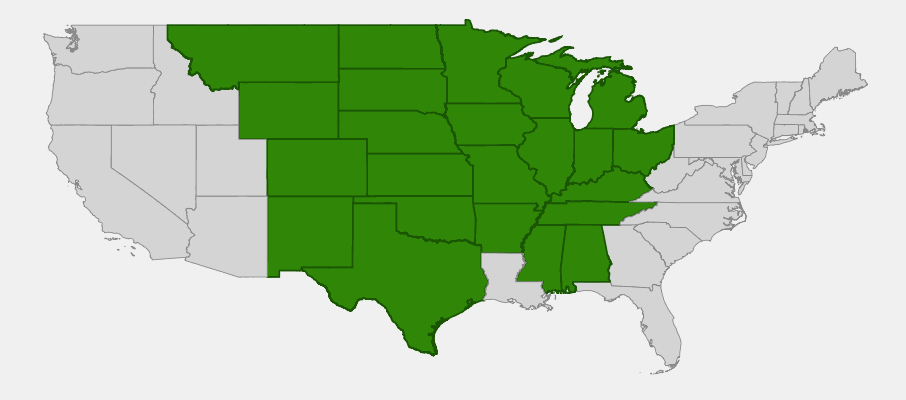

Prairie Larkspur is native to the Great Plains and adjacent regions of North America, with its range centered on the vast grasslands that once stretched from southern Canada to Texas and from the Rocky Mountain foothills east to the deciduous forest margins. This distribution reflects the plant’s specialized adaptation to the unique climate and ecological conditions of the continental interior, including extreme temperature fluctuations, variable precipitation patterns, and the periodic fires that historically shaped prairie ecosystems.

In its natural habitat, Prairie Larkspur is typically found in mixed-grass and tallgrass prairie, dry upland meadows, and the edges of prairie wetlands where soils are well-drained. It shows a particular affinity for calcareous soils and is often found in areas where limestone or chalk bedrock lies close to the surface. The plant thrives in areas that experience the full continental climate — hot summers, cold winters, and the wide day-to-night temperature swings characteristic of the Great Plains interior.

The species occurs from elevations near sea level in eastern portions of its range to over 6,000 feet in the western Great Plains and Rocky Mountain foothills. It is particularly common in the Flint Hills of Kansas, the Sandhills of Nebraska, and the mixed-grass prairie regions of the Dakotas, where it forms part of the diverse wildflower community that supports the region’s rich pollinator fauna.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Prairie Larkspur: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Prairie Larkspur is an excellent choice for gardeners seeking to add vertical interest and unique flower forms to drought-tolerant plantings. While it requires specific growing conditions to thrive, once those conditions are met, it is remarkably low-maintenance and long-lived.

Light

Prairie Larkspur requires full sun for optimal growth and flowering. It evolved in the open grasslands where shade is virtually non-existent, and it will not perform well with less than 8 hours of direct sunlight daily. In partial shade, plants become weak, floppy, and bloom poorly or not at all. The intense sunlight of its native range has shaped every aspect of the plant’s physiology, from its narrow leaves to its drought-tolerance mechanisms.

Soil & Water

Well-drained soil is absolutely critical for Prairie Larkspur success. The plant has evolved a deep taproot system that allows it to access moisture from deep in the soil profile, but it cannot tolerate waterlogged conditions, which quickly lead to root rot. It performs best in sandy, loamy, or clay-loam soils with good drainage and shows a preference for slightly alkaline conditions (pH 7.0–8.5), reflecting its natural occurrence on calcareous prairie soils. Once established, Prairie Larkspur is extremely drought-tolerant and rarely needs supplemental water except during the most severe droughts.

Planting Tips

Prairie Larkspur is best grown from seed, which requires a cold stratification period for reliable germination. Collect seeds in late summer when follicles are brown and dry, then store them in the refrigerator for 60–90 days before planting. Direct sow in fall or early spring, barely covering the seeds with soil. Germination rates are typically low (30–50%), so plant more seeds than you ultimately want plants. Transplanting is difficult due to the taproot, so plan permanent locations carefully.

Pruning & Maintenance

Prairie Larkspur requires minimal maintenance once established. Allow flowers to go to seed to encourage self-seeding and provide seed for birds. The plant naturally dies back to the ground each winter and re-emerges in spring. In cultivation, some gardeners prefer to cut back spent flower spikes to prevent aggressive self-seeding, but in naturalistic prairie plantings, allowing natural seeding is usually preferable.

Landscape Uses

Prairie Larkspur serves specific but important roles in the landscape:

- Prairie gardens — essential component of authentic Great Plains plantings

- Xeriscaping — excellent drought-tolerant vertical element

- Pollinator gardens — specialized nectar source for long-tongued bees and butterflies

- Native plant gardens — adds architectural interest to grassland plantings

- Cut flower gardens — striking in arrangements, though short-lived

- Restoration projects — important for reestablishing native prairie diversity

- Educational gardens — demonstrates unique Great Plains adaptations

Safety Considerations

Important: Like all Delphinium species, Prairie Larkspur contains alkaloids that are toxic to humans and livestock if consumed in significant quantities. While the plant plays an important ecological role and poses minimal risk in typical garden settings, it should be planted with awareness of its toxicity, particularly where livestock might graze or children might be tempted to taste the flowers.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Despite its toxicity to mammals, Prairie Larkspur plays a crucial role in supporting specialized pollinators and serves as an important component of healthy prairie ecosystems.

For Birds

While birds generally avoid Prairie Larkspur due to its alkaloid content, some seed-eating species may occasionally consume small quantities of the seeds. More importantly, the plant indirectly supports birds by providing nectar for the insects that many bird species depend on during breeding season. The tall flower spikes also provide perching sites for small songbirds hunting for insects in prairie environments.

For Mammals

Most mammals instinctively avoid Prairie Larkspur due to its toxic compounds, which actually serves a protective function in the ecosystem. However, this avoidance behavior means the plant poses little actual threat to wildlife under natural conditions. Small mammals may occasionally seek shelter among the plant’s foliage, and the deep root system creates soil structure that benefits burrowing animals.

For Pollinators

Prairie Larkspur is specifically adapted for long-tongued pollinators and serves as a critical nectar source for several specialized species. Bumblebees and other long-tongued bees are the primary pollinators, able to access the nectar stored deep within the flower spurs. Certain butterflies, particularly those with long proboscises like Monarchs and swallowtails, also visit the flowers. Hummingbirds occasionally visit Prairie Larkspur flowers, though they are not the plant’s primary pollinators. The timing of Prairie Larkspur’s bloom — June through July — fills an important gap between spring wildflowers and later summer blooms.

Ecosystem Role

In prairie ecosystems, Prairie Larkspur serves as a structural component that adds vertical diversity to the grassland matrix. Its deep taproot helps break up compacted soil layers and brings nutrients from deep in the soil profile to the surface when leaves decompose. The plant is well-adapted to prairie fires, typically resprouting from its deep root system after burning. Fire actually benefits Prairie Larkspur by reducing competing vegetation and creating the open conditions it requires for optimal growth. As part of the complex prairie plant community, it contributes to the overall resilience and biodiversity of grassland ecosystems.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Prairie Larkspur has a complex relationship with human cultures across the Great Plains, valued for its beauty while respected for its potentially dangerous properties. Various Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains region were well aware of the plant’s toxic nature and generally avoided internal use, though some tribes used it in limited external applications. The Lakota and other Plains tribes occasionally used very small amounts of Prairie Larkspur in ceremonial contexts, always with great caution due to knowledge of its potency.

More commonly, Indigenous peoples used Prairie Larkspur for practical purposes that took advantage of its toxic properties. Some tribes prepared weak infusions from the plant to create natural insecticides for protecting stored foods and clothing from insect pests. The plant’s alkaloids also made it useful for treating external parasites on horses and dogs, though this required careful application to avoid poisoning the animals being treated.

European settlers arriving on the Great Plains quickly learned about Prairie Larkspur’s toxic properties, often the hard way when livestock became ill after grazing areas where the plant was common. This led to the development of range management practices designed to reduce larkspur populations in areas where cattle grazed. Ironically, some of these management practices, including overgrazing and fire suppression, contributed to the decline of native prairie ecosystems that depend on periodic disturbance.

Despite its toxicity concerns, Prairie Larkspur found its way into frontier gardens where settlers appreciated its dramatic flowers and vertical form. Pioneer women often included the striking flower spikes in bouquets and dried arrangements, using them to bring color and elegance to often austere prairie homesteads. The plant’s drought tolerance made it particularly valuable in areas where water was scarce and garden maintenance difficult.

In modern times, Prairie Larkspur has gained recognition as an important component of authentic prairie restoration and conservation efforts. Botanists and ecologists now understand that the plant’s toxicity serves important ecological functions, helping maintain the balance of prairie ecosystems by preventing overgrazing and creating refugia for other plant species. Its specialized pollinator relationships also make it a keystone species for supporting native bee and butterfly populations in grassland environments.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Prairie Larkspur dangerous to have in my garden?

Prairie Larkspur contains toxic alkaloids, but it poses minimal risk in typical garden settings when used responsibly. Avoid planting it where livestock graze or where small children might be tempted to taste the flowers. In residential gardens, the primary precaution is awareness — treat it like any other potentially harmful garden plant such as oleander or castor bean.

Why won’t my Prairie Larkspur seeds germinate?

Prairie Larkspur seeds require cold stratification to break dormancy. Place fresh seeds in slightly moist sand or peat in the refrigerator for 60–90 days before planting. Also, expect low germination rates (30–50%) even under ideal conditions — this is normal for this species. Plant 2–3 times as many seeds as you want plants.

Can I transplant Prairie Larkspur?

Transplanting is difficult and often unsuccessful due to the plant’s deep taproot system. Prairie Larkspur is best grown from seed sown directly where you want the plants to grow. If you must transplant, do so when plants are very small (less than 3 inches tall) and handle the roots extremely carefully.

How long does Prairie Larkspur live?

Prairie Larkspur is a long-lived perennial that can persist for many years when grown in suitable conditions. Individual plants may live 10–20 years or more, and established colonies can persist indefinitely through self-seeding. The key to longevity is providing the well-drained, sunny conditions the plant requires.

Will Prairie Larkspur spread and take over my garden?

No. Prairie Larkspur spreads slowly through self-seeding and does not spread vegetatively like some aggressive perennials. It tends to form modest colonies over time but is not considered invasive. In fact, many gardeners find it challenging to establish and maintain, particularly outside its native range or in less-than-ideal growing conditions.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Prairie Larkspur?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota