Black Walnut (Juglans nigra)

Juglans nigra, commonly known as Black Walnut, is one of the most prized native hardwood trees in North America. This stately member of the Juglandaceae (walnut) family is renowned for its rich, chocolate-brown heartwood — considered among the finest cabinet and furniture woods in the world — and for its distinctively flavored edible nuts enclosed in thick, rough black shells. Standing 50 to 70 feet tall at maturity with a broad, rounded crown, Black Walnut commands attention in any landscape.

Native to a vast range spanning from the eastern Great Plains to the Atlantic seaboard, Black Walnut thrives in rich bottomland soils along streams and rivers, though it adapts well to upland sites with good drainage. The tree produces a chemical compound called juglone in its roots, leaves, and husks that is allelopathic — toxic to many nearby plants including tomatoes, peppers, azaleas, and blueberries. This fascinating chemical defense strategy gives Black Walnut a competitive advantage in the wild but requires thoughtful placement in home landscapes.

Beyond its timber and nut value, Black Walnut plays a vital ecological role in eastern forests. Its nuts are a critical high-fat food source for squirrels, deer, and many bird species, while its large spreading canopy provides shade and nesting habitat. For landowners and native plant enthusiasts in the Dakotas and western Minnesota, Black Walnut represents the western edge of its natural range, growing best in sheltered bottomlands and along waterways where moisture and rich soils support its growth.

Identification

Bark

Young Black Walnut bark is smooth and olive-brown, becoming deeply furrowed with age into a distinctive pattern of dark brown to black interlocking ridges separated by tan or gray furrows. The bark pattern is sometimes described as resembling a diamond lattice. On mature trees, the bark can be 2 to 3 inches thick and provides excellent insulation against fire damage.

Leaves

The leaves are pinnately compound, 12 to 24 inches long, with 13 to 23 finely serrated leaflets arranged alternately along the rachis. Each leaflet is 2 to 5 inches long, lance-shaped, with a pointed tip and slightly asymmetrical base. The foliage is bright yellow-green in spring, darkening to a rich green in summer. When crushed, the leaves emit a distinctive spicy, somewhat citrusy aroma. Fall color is a modest yellow, and leaves drop relatively early in autumn.

Flowers & Fruit

Black Walnut is monoecious, producing both male and female flowers on the same tree. Male flowers appear as pendulous green catkins 3 to 5 inches long in late spring, while the small, inconspicuous female flowers form in clusters of 2 to 5 at branch tips. The fruit is a round, green drupe 1.5 to 2.5 inches in diameter with a thick, fleshy husk that stains hands and surfaces dark brown to black. Inside the husk is the extremely hard, corrugated shell containing the rich, distinctively flavored nut meat. Fruits ripen in September and October, falling to the ground in heavy crops.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Juglans nigra |

| Family | Juglandaceae (Walnut) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 50–70 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | April – June |

| Flower Color | Greenish (catkins) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–9 |

Native Range

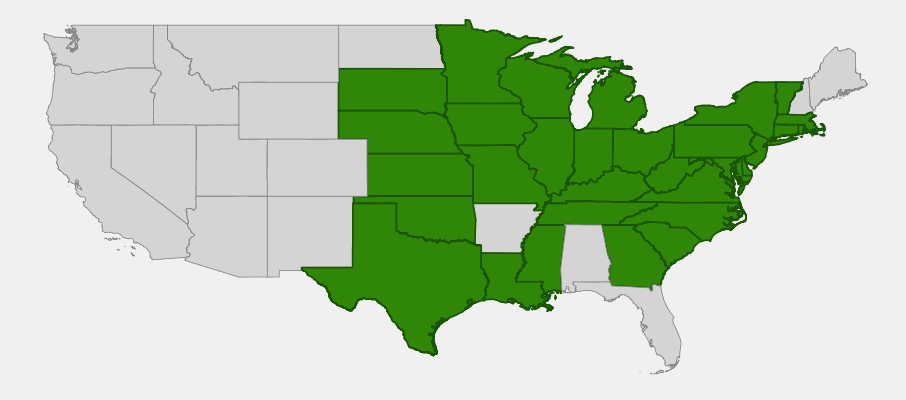

Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) is native to a broad range across North America, growing naturally in rich bottomlands, well-drained uplands, stream banks, mixed hardwood forests. In the United States, it occurs in Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin. The species is found from Sea level – 4,500 ft elevation, adapting to the local conditions within each region of its range.

Within its native range, Black Walnut is associated with the Eastern Deciduous Forest, Central Hardwoods ecoregion, where it grows alongside species such as White Oak, Red Oak, Sugar Maple, Hickory, Basswood. These plant communities have co-evolved over thousands of years, forming the complex ecological relationships that characterize healthy native landscapes. The presence of Black Walnut in a plant community is often an indicator of good site conditions and ecological integrity.

In the Dakotas and western Minnesota, Black Walnut occurs naturally in suitable habitats and is well-adapted to the region’s continental climate with its cold winters, warm summers, and variable precipitation. Conservation efforts and native plant restoration projects are helping to maintain and expand populations of Black Walnut throughout the region, ensuring that this valuable native species continues to thrive for future generations.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Black Walnut: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Light

Black Walnut is a full-sun species that requires at least 6 to 8 hours of direct sunlight daily for optimal growth. It does not tolerate heavy shade and will gradually decline under canopy cover. In the Dakotas, plant it in open areas or along south-facing edges where it will receive maximum sunlight.

Soil & Water

This tree thrives in deep, well-drained, fertile loam soils with a pH between 6.0 and 7.5. It is particularly fond of rich alluvial soils along streams and rivers. While established trees are moderately drought-tolerant, they perform best with consistent moisture. Avoid planting in heavy clay or poorly drained sites, as Black Walnut is intolerant of waterlogged soils. In the northern Great Plains, seek sheltered bottomland sites with the deepest, richest soil available.

Planting Tips

Plant container-grown trees in spring after the last frost. Black Walnut has a deep taproot, so choose the permanent site carefully — transplanting large specimens is extremely difficult. Space trees at least 40 to 50 feet apart. Be mindful of the juglone zone: avoid planting tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, azaleas, rhododendrons, blueberries, or mountain laurels within 50 to 80 feet of Black Walnut trees.

Pruning & Maintenance

Prune in late winter while dormant to shape the crown and remove dead or crossing branches. If growing for timber, prune lower branches gradually to produce a straight, clear trunk. Collect fallen nuts and husks in autumn to reduce mess and prevent volunteer seedlings. The tree is relatively pest-free, though thousand cankers disease (carried by the walnut twig beetle) has become a serious threat in some regions.

Landscape Uses

- Shade tree for large properties with ample space

- Nut production — named cultivars available for larger, easier-to-crack nuts

- Timber investment — veneer-quality logs are extremely valuable

- Riparian buffer plantings along streams and waterways

- Wildlife food source in naturalized settings

- Windbreak component in multi-row shelterbelts

Wildlife & Ecological Value

For Birds

Black Walnut nuts are consumed by woodpeckers, Blue Jays, crows, and Wild Turkeys. The spreading canopy provides excellent nesting and roosting habitat for a variety of songbirds, raptors, and owls. The caterpillars of several moth species that feed on walnut foliage are important food for warblers and other insectivorous birds during the breeding season.

For Mammals

Eastern Fox Squirrels and Gray Squirrels are the primary dispersers of Black Walnut, burying thousands of nuts each fall. Many of these cached nuts are never retrieved and germinate the following spring, making squirrels essential to Black Walnut regeneration. White-tailed Deer browse young seedlings and occasionally eat the nuts. Raccoons, Black Bears, and even mice feed on the nutritious nut meats when they can access them.

For Pollinators

As a wind-pollinated species, Black Walnut is not a major nectar source. However, the broad canopy supports numerous caterpillar species including the Luna Moth, Regal Moth, and Walnut Sphinx Moth, whose larvae feed on the foliage. These caterpillars in turn support bird populations. The tree’s root zone provides habitat for ground-nesting bees and other soil-dwelling insects.

Ecosystem Role

Black Walnut plays a unique ecological role through allelopathy — the production of juglone, which inhibits the growth of competing plants. This chemical strategy creates a distinctive understory community beneath walnut trees, favoring juglone-tolerant species like Kentucky Bluegrass, Virginia Creeper, and certain ferns while excluding many other plants. The deep root system helps stabilize stream banks and access deep water tables, while the heavy nut crop provides a critical fall and winter food source for wildlife.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Black Walnut has been valued by humans for thousands of years. Indigenous peoples across eastern North America, including the Cherokee, Comanche, Dakota, and Iroquois nations, harvested the nuts as a staple food. The nuts were eaten fresh, dried for winter storage, or pounded into meal and added to corn bread and other dishes. The oil extracted from the nuts was used for cooking and as a body rub. The inner bark was used medicinally as a laxative, and the husk dye was used to color baskets and other crafts.

European settlers quickly recognized Black Walnut’s value and began commercial harvesting of both nuts and timber. The wood became the standard for fine furniture, gun stocks (including the iconic M1 Garand rifle stock of World War II), and cabinetry. Today, a single large Black Walnut tree with a straight, clear trunk can be worth thousands of dollars as veneer timber. Walnut logging has been so profitable that “walnut rustling” — illegal harvesting of trees from private and public land — remains an ongoing problem in many states.

The nut husks produce one of the most permanent natural dyes known, yielding rich brown and black colors that have been used for centuries to dye fabrics, stain wood, and create ink. Today, Black Walnut continues to be cultivated both for nut production (with improved cultivars producing larger, thinner-shelled nuts) and for timber plantations. The nuts are used in baking, ice cream, and confections, commanding premium prices for their distinctively bold, earthy flavor that cannot be replicated by the milder English walnut.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will Black Walnut kill nearby plants?

Black Walnut produces juglone, a chemical toxic to many plants including tomatoes, peppers, azaleas, blueberries, and apple trees. Keep sensitive plants at least 50–80 feet away. Many plants are juglone-tolerant, including most grasses, beans, squash, and trees like oaks and maples.

How long does it take for Black Walnut to produce nuts?

Seedling trees typically begin producing nuts at 12–15 years of age, with significant crops starting at around 20–25 years. Grafted cultivars can produce nuts as early as 4–6 years after planting. Full production occurs at 30+ years.

Can Black Walnut grow in the Dakotas?

Yes, Black Walnut grows in the eastern portions of North and South Dakota, particularly in sheltered river bottoms and valleys. It reaches the western edge of its natural range here and benefits from the protection of windbreaks and the rich alluvial soils found along waterways.

How do you crack Black Walnut shells?

Black Walnut shells are extremely hard. Traditional methods include placing nuts on a hard surface and striking with a hammer. Commercial-grade nutcrackers designed specifically for Black Walnuts are available. First, remove the husks (wearing gloves to avoid staining), dry the nuts for 2–4 weeks, then crack.

Is Black Walnut wood really that valuable?

Yes. High-quality Black Walnut veneer logs can sell for $5,000 to $20,000 or more per log, depending on size and figure. Even lower-grade lumber sells for premium prices. This makes Black Walnut one of the most financially valuable native trees you can grow.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Black Walnut?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota