Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris)

Matteuccia struthiopteris, commonly known as Ostrich Fern, Fiddlehead Fern, or Shuttlecock Fern, is one of North America’s most recognizable and beloved native ferns. This magnificent species creates dramatic, vase-shaped colonies that can reach heights of 2 to 6 feet, making it a spectacular choice for woodland gardens, shade landscaping, and naturalistic plantings throughout its extensive northern range.

The common name “Ostrich Fern” comes from the plant’s striking resemblance to ostrich plumes, with its large, feathery sterile fronds forming elegant circular crowns that emerge from central crowns each spring. These impressive fronds are complemented by much smaller, dark brown fertile fronds that appear in late summer, creating an attractive seasonal contrast that adds year-round architectural interest to the landscape.

Beyond its ornamental value, Ostrich Fern holds special significance as the source of edible fiddleheads—the tightly coiled young fronds that emerge in spring and are considered a seasonal delicacy throughout the northern United States and Canada. This dual-purpose nature, combined with its exceptional shade tolerance and ability to naturalize in moist woodland conditions, has made Ostrich Fern a cornerstone species for ecological restoration projects and sustainable landscaping from coast to coast.

Identification

Ostrich Fern is easily identified by its distinctive growth habit and seasonal appearance. The plant forms large, circular colonies through extensive underground rhizomes, with individual crowns producing dramatic clusters of fronds that create the characteristic vase or shuttlecock shape that gives the fern its common names.

Sterile Fronds

The most prominent feature of Ostrich Fern is its large sterile (vegetative) fronds, which typically measure 3 to 5 feet long and up to 12 inches wide. These fronds are lance-shaped and pinnate-pinnatifid, meaning they are deeply divided into numerous leaflets that are themselves deeply lobed. The fronds emerge in a tight circular pattern from the central crown, creating the characteristic vase shape. Each frond has a stout, grooved stipe (stem) that is typically one-quarter to one-third the length of the entire frond. The stipe is notable for having a deep groove on the upper surface and distinctive dark, chaff-like scales at the base.

Fertile Fronds

In late summer, Ostrich Fern produces much shorter fertile fronds (1 to 2 feet tall) that are completely different in appearance from the sterile fronds. These fertile fronds are dark brown to black, with tightly contracted pinnae that protect the developing spores. They persist through winter, creating an attractive contrast against snow and providing year-round structural interest. The fertile fronds are often called “spore fronds” and are crucial for identification, as they distinguish Ostrich Fern from other large fern species.

Fiddleheads

The famous fiddleheads are the tightly coiled emerging fronds that appear in early spring, typically from late April through mid-May depending on latitude and seasonal temperatures. These coiled structures are covered with brown, papery scales and can be 2 to 8 inches tall when ready for harvesting. The fiddleheads emerge from the central crown and gradually unfurl into the full-sized sterile fronds over a period of 2 to 3 weeks.

Root System

Ostrich Fern spreads via thick, black rhizomes that can extend several feet from the parent plant underground. These rhizomes produce new crowns at intervals, allowing the fern to form extensive colonies over time. The root system is shallow but extensive, making it excellent for erosion control on slopes and stream banks.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Matteuccia struthiopteris (syn. Pteretis nodulosa) |

| Family | Onocleaceae (Sensitive Fern) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Fern |

| Mature Height | 2–6 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Spores Released | Late Summer – Fall |

| Fiddlehead Season | Late April – Mid May |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–7 |

Native Range

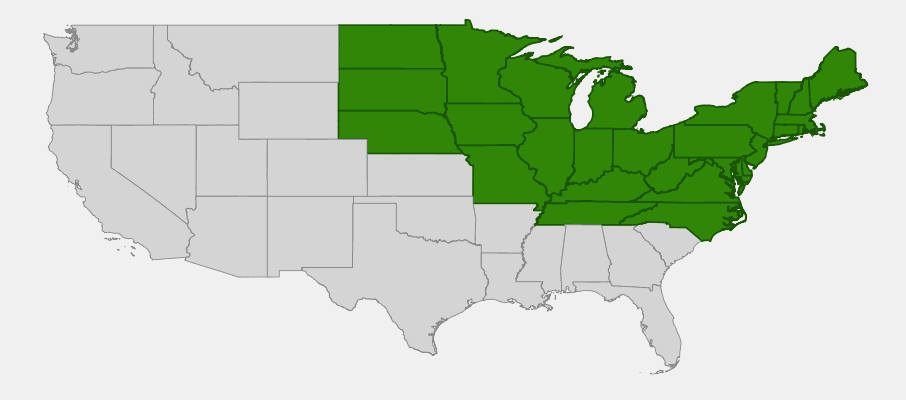

Ostrich Fern has one of the most extensive ranges of any North American fern, occurring naturally across much of Canada and the northern United States. The species is circumpolar, meaning it also occurs in northern Europe and Asia, making it one of the most widely distributed ferns in the Northern Hemisphere. This broad distribution reflects the species’ ancient origins and its remarkable adaptability to varied but consistently cool, moist conditions.

In North America, Ostrich Fern ranges from Newfoundland west to Alaska, and south to Virginia, Kentucky, Illinois, Iowa, and North Dakota. The southern limits of its range are typically determined by summer heat tolerance rather than winter cold, as this fern thrives in areas with cool summers and adequate moisture throughout the growing season.

Throughout its native range, Ostrich Fern typically occurs in rich, moist soils in partially shaded to fully shaded locations. It is commonly found along stream banks, in floodplains, rich woods, swamps, and at the edges of wetlands. The species often forms extensive colonies in suitable habitat, creating spectacular displays that can cover acres in pristine woodland conditions.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Ostrich Fern: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Ostrich Fern is one of the most rewarding native ferns to grow, offering spectacular architectural presence with minimal maintenance once established. Its preference for shade and moist conditions makes it ideal for challenging areas where many other plants struggle.

Light

Ostrich Fern performs best in partial to full shade, thriving in the dappled light conditions found on the floor of deciduous forests. It can tolerate morning sun but must have protection from hot afternoon sun, which can scorch the fronds and cause the plant to go dormant prematurely. In very deep shade, the fern will still grow but may produce smaller fronds and spread more slowly.

Soil & Water

This fern requires consistently moist, rich, well-draining soil with high organic matter content. It thrives in slightly acidic to neutral pH (5.5–7.0) but is quite adaptable to different soil types as long as moisture is consistent. The ideal soil mimics forest floor conditions: loamy, high in organic matter, and never completely dry. Ostrich Fern is particularly well-suited to areas with seasonal flooding or consistently high moisture, making it excellent for rain gardens and low-lying areas.

Planting Tips

Plant Ostrich Fern in early spring or fall when temperatures are cool and moisture is abundant. Space plants 3 to 4 feet apart if creating a colony, or use single specimens with room to spread. The fern establishes best from container-grown stock or dormant rhizome divisions. When planting, ensure the crown is at soil level and provide a 2-3 inch mulch layer to maintain moisture and suppress weeds.

Pruning & Maintenance

Ostrich Fern requires minimal maintenance. Remove old, brown fronds in late fall or early spring before new growth emerges. The fertile fronds can be left standing through winter for visual interest and wildlife value, or removed if a tidier appearance is desired. Divide overcrowded colonies every 4-5 years by carefully separating rhizomes in early spring or fall.

Landscape Uses

Ostrich Fern’s versatility and dramatic presence make it valuable in many garden settings:

- Woodland gardens — creates spectacular naturalistic displays

- Shade borders — provides bold texture and height

- Rain gardens — excellent for moisture management

- Stream and pond edges — softens hardscaping and prevents erosion

- Foundation plantings — adds seasonal interest on north sides of buildings

- Mass plantings — creates dramatic colonies in large spaces

- Container gardens — makes striking specimen in large pots

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Ostrich Fern provides important ecological benefits throughout its range, supporting wildlife through habitat structure, food resources, and soil stabilization services.

For Birds

Many bird species utilize Ostrich Fern colonies for nesting and cover. Ground-nesting birds like Wood Thrushes and various warbler species often build nests within or adjacent to fern colonies, where the large fronds provide excellent concealment and protection from predators. The dense growth also creates important foraging habitat for birds that feed on insects and other invertebrates that thrive in the moist, shaded microenvironment.

For Mammals

White-tailed Deer occasionally browse Ostrich Fern fronds, particularly the emerging fiddleheads in spring, though the fern is not a preferred food source. Small mammals like chipmunks and ground squirrels use the dense colonies for cover and travel corridors. The extensive root systems provide habitat for various soil-dwelling invertebrates that form the base of woodland food webs.

For Pollinators

While ferns do not produce flowers, Ostrich Fern colonies create the moist, shaded microhabitat conditions that many beneficial insects require for part of their life cycle. The decomposing organic matter around fern colonies supports diverse invertebrate communities that provide food for beneficial predatory insects and spiders that help control garden pests.

Ecosystem Role

Ostrich Fern plays a crucial role in woodland ecosystem health through its soil-building and erosion control properties. The large fronds decompose each fall to create rich organic matter that improves soil structure and fertility. The extensive rhizome system helps stabilize soil on slopes and stream banks, while the large fronds help retain moisture and moderate soil temperature fluctuations in woodland environments.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Ostrich Fern holds a place of particular importance in North American culinary and cultural traditions, primarily due to its edible fiddleheads, which have been harvested and consumed for thousands of years by Indigenous peoples and continue to be a celebrated seasonal delicacy across the northern United States and Canada.

Indigenous peoples throughout the fern’s range, including the Abenaki, Ojibwe, and many other tribal nations, have traditionally harvested fiddleheads as an important spring food source. The emerging fronds provided crucial nutrition during the “hungry time” of late spring when winter food stores were depleted but other wild foods had not yet become available. Traditional preparation involved careful cleaning to remove the brown scales, followed by boiling or steaming to eliminate potential toxins and bitter compounds.

European settlers adopted fiddlehead harvesting from Indigenous peoples, and the practice became deeply embedded in the foodways of northern New England, the Maritime Provinces, and other regions where Ostrich Fern is abundant. Today, fiddleheads are commercially harvested and sold in specialty markets throughout North America, with Maine and the Canadian Maritimes being major commercial production regions.

Beyond food use, Ostrich Fern has been valued for its ornamental qualities since at least the 1800s, when Victorian gardeners embraced ferns for shaded gardens and conservatories. The species’ dramatic form and reliability made it a favorite for estate gardens and public parks, a tradition that continues today in naturalistic landscape design.

Modern ecological restoration projects frequently use Ostrich Fern to reestablish native plant communities in degraded woodland and wetland areas. The species’ rapid establishment, soil-building properties, and ability to suppress invasive plants make it particularly valuable for restoration work in northern temperate regions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Ostrich Fern fiddleheads safe to eat?

Yes, when properly harvested and prepared. Only harvest tightly coiled fiddleheads that are less than 6 inches tall, clean them thoroughly to remove all brown scales, and cook them completely by boiling for 15 minutes or steaming for 10-12 minutes. Never eat them raw, and never harvest more than half of the fiddleheads from any one crown to ensure the plant’s survival.

How fast does Ostrich Fern spread?

Ostrich Fern spreads at a moderate rate, typically expanding 1-2 feet per year through underground rhizomes under ideal conditions. The rate depends on soil moisture, fertility, and light conditions. In very favorable conditions with rich, consistently moist soil, it can spread more aggressively.

Will Ostrich Fern take over my garden?

Ostrich Fern can form large colonies but is generally not considered invasive in its native range. It spreads predictably through rhizomes and can be easily controlled by removing unwanted shoots or installing root barriers. Most gardeners find the spreading habit beneficial for creating naturalistic ground cover in shaded areas.

Can I grow Ostrich Fern in containers?

Yes, Ostrich Fern grows well in large containers (at least 18 inches wide and deep) with consistent moisture and partial to full shade. Container plants may need winter protection in colder zones, and they’ll require regular division every 2-3 years to prevent overcrowding.

When do the fronds die back in fall?

The large sterile fronds typically die back with the first hard frost, usually in mid to late fall depending on location. The smaller fertile fronds persist through winter, providing structural interest until new growth emerges in spring. Clean-up can be done in late fall or early spring before new fiddleheads emerge.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Ostrich Fern?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota