Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

Echinacea purpurea, the Purple Coneflower, is arguably the most iconic native wildflower of eastern North America — and with good reason. Its bold, rosy-purple ray petals surrounding a prominent, spiny orange-brown central cone are instantly recognizable and have made it one of the most widely grown perennials in the world. A member of the aster family (Asteraceae), Purple Coneflower combines spectacular ornamental appeal with exceptional ecological value: it is a superb pollinator plant, a critical seed source for goldfinches and other seed-eating birds, and a remarkably tough, drought-tolerant perennial that thrives in challenging garden conditions.

In bloom from June through September, Purple Coneflower performs during the peak of the gardening season when pollinators are most active and gardeners most appreciate a reliable show. The plants grow 2 to 4 feet tall in full sun with sturdy, upright stems that rarely need staking. Each plant produces dozens of flower heads over the long bloom season, and when the petals drop, the distinctive spiny seed cones remain standing through fall and winter — providing food for American Goldfinches and other finches that cling to the cones and extract seeds with remarkable acrobatic skill.

Purple Coneflower is also notable for its role in herbal medicine — preparations from Echinacea species are among the best-selling herbal products in North America and Europe, marketed for immune support. While the scientific evidence for many claimed benefits remains mixed, the plant’s importance to Indigenous cultures as a medicinal plant spans centuries. In the garden, its beauty, toughness, and wildlife value need no qualification — Purple Coneflower belongs in every native plant garden in the northeastern United States.

Identification

Purple Coneflower grows as an upright, clump-forming perennial reaching 2 to 4 feet tall in full sun and blooming from late June through September. The stems are stiff, somewhat rough (hairy), and branch in the upper third to produce multiple flower heads per stem. The plant spreads slowly by short rhizomes to form clumps 2 to 3 feet wide at maturity. The name Echinacea comes from the Greek echinos, meaning “hedgehog” or “sea urchin” — a reference to the spiny central cone of the flower head.

Leaves

The basal leaves are large, broadly ovate, 4 to 8 inches long with coarsely toothed margins and a rough, hairy surface on both sides. The stem leaves are alternate, progressively smaller up the stem, and lance-shaped. All leaves have a rough texture — a distinctive feature that distinguishes Echinacea from similar composites. The veins are prominently raised on the underside, and the petioles on lower leaves are long, giving the plant an attractive, vigorous appearance throughout the growing season.

Flowers & Fruit

The flower heads are large and showy — 3 to 5 inches in diameter — with 12 to 20 purple-pink ray florets that droop distinctively backward away from the raised central cone. This drooping posture is characteristic of Echinacea and distinguishes it from asters and other composites. The central cone is a prominent dome of spiny orange-brown disc florets that mature from the outside inward over several weeks. The bloom period extends from June through September, with peak bloom in July and August. After the ray petals drop, the cone persists through winter, hardening and darkening to a deep brown-black, and providing seed for birds well into the cold months.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Echinacea purpurea |

| Family | Asteraceae (Aster / Composite) |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous Perennial |

| Mature Height | 2–4 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate (Drought Tolerant) |

| Bloom Time | June – September |

| Flower Color | Purple-pink with orange-brown central cone |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

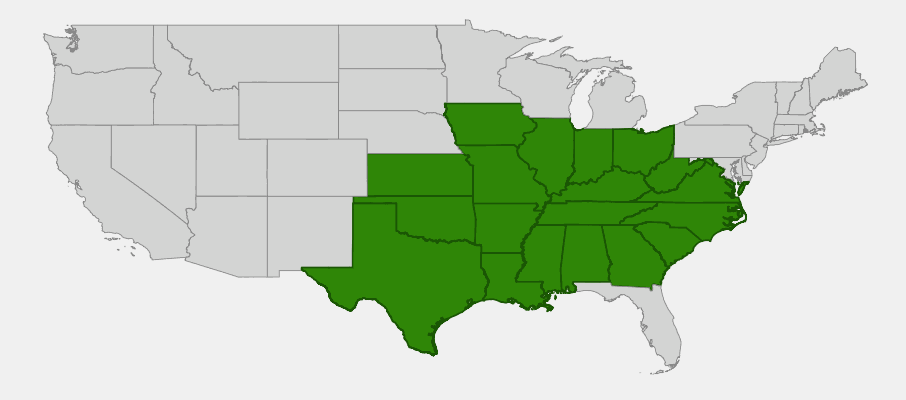

Native Range

Purple Coneflower is native to the central and eastern United States, with its core native range in the south-central states — Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. In its natural habitat it grows in moist to dry open woods, meadows, prairies, and roadsides, preferring full sun and well-drained soils. The species has been so extensively cultivated and naturalized beyond its original range that determining the precise boundaries of its truly native distribution is complex.

In New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, Purple Coneflower is widely cultivated and has naturalized in many areas, appearing along roadsides, in old fields, and in disturbed areas. Whether it is truly native to these northeastern states or represents naturalized populations from centuries of cultivation is debated by botanists. Regardless, it is an ecologically valuable species that supports native pollinators and wildlife throughout the region, and it is a standard component of native plant gardens and restoration plantings across the northeastern United States.

The genus Echinacea contains nine species, all native to North America, primarily in the central and eastern regions. E. purpurea is the most widely distributed and easily cultivated species. It has been selectively bred into dozens of cultivars with white, yellow, orange, and bicolor flowers, though the original purple-pink form remains ecologically superior for wildlife support. The species is remarkably adaptable, thriving in gardens from the Deep South to southern Canada, tolerating both drought and occasional flooding.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Purple Coneflower: New York, Pennsylvania & New Jersey

Growing & Care Guide

Purple Coneflower is one of the easiest and most adaptable native perennials for the sunny garden. It thrives in challenging conditions — dry, hot, sunny sites with lean soils — where many garden plants struggle, and it asks for very little care in return for a long, spectacular bloom season.

Light

Full sun is essential for best performance. Purple Coneflower in full sun produces compact, strong-stemmed plants with maximum flowering. It tolerates some light afternoon shade but becomes taller and more open in reduced light, and shade increases disease susceptibility. In the northeastern states where summers are often cloudy, err on the side of maximum sun exposure — at least 6 to 8 hours of direct sunlight daily.

Soil & Water

Purple Coneflower tolerates a remarkable range of soil conditions — from well-drained sandy soils to average loam to moderately heavy clay — as long as drainage is reasonable. It actually performs better in average to lean soils than in rich, fertile ground, which produces excessive leafy growth and weaker stems. Once established, it is notably drought tolerant — the deep taproot allows it to access water during dry summer periods when shallower-rooted plants wilt. Avoid wet, poorly drained soils where the crown can rot. No fertilization is needed or desirable.

Planting Tips

Plant Purple Coneflower in spring or fall. Space plants 18 to 24 inches apart to allow for mature spread. It establishes quickly from container stock and often blooms its first year. Plants grown from seed typically bloom in the second year. Echinacea self-sows freely — allow some seeds to remain on the plants for winter birds, and expect seedlings to appear nearby. Weed or relocate unwanted seedlings when small. Divide established clumps every 3–4 years in spring to maintain vigor; clumps that have become dense and woody in the center may benefit from division and replanting of the vigorous outer sections.

Pruning & Maintenance

Leave seed cones standing through winter — American Goldfinches depend on them as a winter food source, and the architectural form of the dried cones adds winter garden interest. Cut all stems back to the ground in late winter or early spring before new growth emerges. Deadheading spent flower heads during the bloom season prolongs blooming by preventing seed set, but it also removes the valuable seed food source for birds — a trade-off to consider. Echinacea is generally free of serious pest and disease problems, though it can develop aster yellows (a phytoplasma disease) that causes distorted, yellowed growth — infected plants should be removed and destroyed.

Landscape Uses

- Prairie and meadow planting — a signature plant in naturalistic sunny gardens

- Pollinator garden anchor — superb butterfly and native bee plant

- Mid-border perennial — upright form works well in mixed borders

- Cut flower garden — long-lasting in fresh arrangements

- Dry, challenging sites — thrives where irrigation is limited

- Wildlife garden — flowers for pollinators, seeds for birds, winter interest

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Purple Coneflower is a wildlife powerhouse, supporting an extraordinary diversity of insects, birds, and other wildlife throughout its extended bloom season and beyond.

For Birds

The seed cones of Purple Coneflower are among the most important winter food sources for seed-eating birds in the northeastern garden. American Goldfinches are the most devoted consumers, often visiting the same plant repeatedly as they extract seeds with their specialized bills. House Finches, Purple Finches, Pine Siskins, and Dark-eyed Juncos also consume the seeds. The dried cones attract birds from late summer through winter, and a patch of coneflowers left standing through the cold season is effectively a “bird feeder” that requires no maintenance or replenishment.

For Mammals

White-tailed deer occasionally browse coneflower foliage, though it is not heavily preferred and the rough, hairy leaves discourage browsing. Small mammals including mice and voles consume fallen seeds from the ground below the plants. Rabbits may nibble young plants in spring — protective caging for the first season may be advisable in areas with heavy rabbit pressure.

For Pollinators

Purple Coneflower is an exceptional pollinator plant of the highest caliber. The large, open flower heads are easily accessible to insects of all sizes, and the long bloom season (June–September) provides nectar and pollen during the peak of the pollinator season. Bumble bees, solitary bees, sweat bees, mining bees, and leafcutter bees all visit regularly. Monarch butterflies, swallowtails, fritillaries, skippers, and dozens of other butterfly species nectar at the flowers. The species also supports specialist insects — the Silvery Checkerspot butterfly (Chlosyne nycteis) uses Echinacea as a larval host plant in some areas. Beneficial wasps and beetles that prey on garden pests are frequent visitors to the flowers as well.

Ecosystem Role

In meadow and prairie plant communities, Purple Coneflower is a keystone species — its abundant, accessible flowers support a diverse pollinator community that in turn benefits all the other flowering plants in the garden through cross-pollination. Its persistent seed cones extend the food supply for seed-eating birds well into winter when other food sources are scarce. The plant’s deep taproot system stabilizes soil, accesses subsoil moisture and nutrients, and contributes organic matter as it decomposes seasonally. As part of a diverse native plant community, Purple Coneflower anchors a web of ecological relationships that sustains garden biodiversity far beyond its own individual contribution.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Purple Coneflower has one of the richest ethnobotanical histories of any North American native plant. Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and eastern woodlands used Echinacea species — particularly E. angustifolia and E. purpurea — as one of their most important medicinal plants. Documented uses include treatments for toothache (the numbing effect of root preparations on the tongue and gums is immediate and dramatic), snake bite, infections, wounds, colds, and various inflammatory conditions. The Lakota, Cheyenne, Dakota, Omaha, Pawnee, and many other nations had distinct medicinal traditions centered on Echinacea. The numbing sensation produced by chewing the root — caused by alkylamides that tingle on the tongue — was a key indicator of potency.

European settlers quickly adopted Echinacea from Indigenous practitioners, and by the late 19th century it had become one of the most widely prescribed botanical remedies in America. H.C.F. Meyer, a Nebraska patent medicine seller, popularized “Meyer’s Blood Purifier” (containing Echinacea) in the 1880s. When he sent samples to Lloyd Brothers — a prominent Cincinnati pharmaceutical firm — along with claims of cures for rattlesnake bite and various infections, he was initially dismissed. But following investigations by John Uri Lloyd and eclectic physician John King, Echinacea became one of the most prescribed herbs in American medicine by 1900.

Today, Echinacea products — primarily based on E. purpurea and E. angustifolia — are among the best-selling herbal supplements worldwide, particularly in Germany, the United States, and Canada, where they are marketed for immune support and cold prevention. Clinical research on Echinacea’s effectiveness has produced mixed results, with some studies showing modest benefit in reducing cold duration and others finding no significant effect. The plant remains a major commercial crop in the United States and Europe, with large-scale cultivation in the Midwest and Rocky Mountain states. In the garden, its ornamental and ecological value far outweigh any medicinal application.

Frequently Asked Questions

Should I deadhead Purple Coneflower?

This is a trade-off. Deadheading spent flowers encourages the plant to produce more blooms and extends the flowering season. However, the persistent seed cones left standing after the ray petals drop are an important winter food source for goldfinches and other birds. A good compromise: deadhead some flowers during the bloom season to encourage reblooming, but leave a significant number of seed cones standing through winter for bird food.

Why are my coneflowers getting monstrous, deformed flowers?

This is likely aster yellows disease — a phytoplasma infection transmitted by leafhoppers that causes distorted, greenish, cone-less flowers and stunted growth. It cannot be treated. Remove and destroy infected plants to prevent the disease from spreading to neighboring plants. Do not compost infected material. Replace with new plants and manage leafhoppers with appropriate measures.

Are fancy hybrid Echinacea cultivars as good for wildlife as the straight species?

For the most part, no. Many of the newer hybrid Echinacea cultivars with unusual flower forms (double flowers, reflexed petals, unusual colors) have reduced nectar and pollen, altered flower structure that makes them less accessible to pollinators, and reduced seed viability. For maximum wildlife value, use the straight species Echinacea purpurea with its original purple-pink flowers. The basic species is also the most vigorous and longest-lived in the garden.

How long does Purple Coneflower live?

In well-drained soil with full sun, Purple Coneflower is a long-lived perennial that may persist for a decade or more. It also self-sows reliably, so even if individual plants decline after many years, new seedlings ensure the continued presence of the plant in your garden. Dividing clumps every 3–4 years also helps maintain vigor.

Can I grow Purple Coneflower from seed?

Yes — Echinacea is easily grown from seed. Collect seeds from ripe cones in fall (when the cones are dry and dark brown), store them dry over winter, and plant in spring after the last frost or start indoors 8–10 weeks before the last frost. Seeds may benefit from cold stratification (30–90 days of moist cold) to improve germination rate. Plants started from seed typically bloom in their second year.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Purple Coneflower?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: New York · Pennsylvania