Water Birch (Betula occidentalis)

Betula occidentalis, known as Water Birch, Rocky Mountain Birch, or Red Birch, is the native birch of the mountain streams and riparian corridors of western North America. Unlike the familiar white-barked birches of the East, Water Birch is distinguished by its distinctive dark reddish-brown to bronze bark covered with conspicuous pale horizontal lenticels — one of the most beautiful bark patterns among western native trees. This graceful small tree or large shrub lines countless mountain streams from Alaska and the Yukon south through the Rockies to New Mexico and California, bringing its elegant, airy canopy and exceptional wildlife value to some of the most dramatic landscapes on the continent.

Water Birch occupies a critical ecological niche in western riparian systems, stabilizing stream banks against erosion, shading and cooling stream water (improving habitat for trout and other cold-water species), and providing food and cover for a remarkable diversity of wildlife. Its catkins are among the earliest spring food sources in mountain stream corridors, and its seeds feed finches and other small birds through winter. Beavers frequently use Water Birch as a construction and food resource, and the dense, multi-stemmed thickets it forms are prime nesting habitat for many songbirds.

For gardeners and restoration practitioners in the Intermountain West, Water Birch is an excellent choice for rain gardens, bioswales, pond and stream edges, and any site that receives seasonal or consistent moisture. Its adaptability to cold mountain climates (surviving to Zone 2 in Alaska), moderate growth rate, spectacular winter bark, and ecological richness make it one of the most rewarding native trees for wet and riparian planting in western landscapes.

Identification

Water Birch typically grows as a large multi-stemmed shrub or small tree, reaching 5 to 20 feet (1.5–6 m) in height, though occasionally to 25 feet in favorable conditions. The multi-stemmed growth form — often with numerous trunks arising from a common base — gives it a graceful, clumping appearance along streambanks. Its most immediately distinctive feature is the bark: dark reddish-brown to bronze with cream to white horizontal lenticels (breathing pores), which give the trunk and branches a striking striped pattern quite unlike any other western native tree.

Bark

The bark is perhaps Water Birch’s most celebrated feature. Young stems are reddish-brown to dark bronze and covered with prominent, raised white or pale cream lenticels arranged in horizontal bands. Unlike Paper Birch (B. papyrifera), Water Birch bark does not peel in papery sheets — it remains smooth to slightly rough, becoming more furrowed only on the oldest trunks. In winter, when the leaves have fallen, the glowing reddish-bronze trunks lit by low winter sun create one of the most beautiful visual effects of any native western plant. The branches show this same warm bronze color, which becomes more orange-red in full sun exposure — one reason for the alternate common name “Red Birch.”

Leaves

The leaves are ovate to nearly triangular, 1 to 3 inches (2.5–7.5 cm) long, with a sharply pointed tip and doubly serrate (double-toothed) margins — a typical birch characteristic. The upper surface is shiny dark green; the underside is pale green with prominent veins and small resinous glands. Leaves are arranged alternately on the stems. In autumn, foliage turns a warm golden-yellow before dropping, providing a reliable fall color display in riparian corridors. The petioles (leaf stalks) are slender and often slightly glandular-hairy.

Flowers & Fruit

Like all birches, Water Birch produces separate male and female catkins on the same plant (monoecious). The male catkins are long, slender, and pendulous — up to 2.5 inches (6 cm) long — forming in late summer and overwintering on the plant before expanding and releasing pollen in very early spring, often before the leaves emerge. The female catkins are shorter and more erect, maturing into small, cone-like structures about 1 inch (2.5 cm) long that contain numerous tiny winged nutlets. These seeds ripen in late summer and are released gradually through fall and winter, providing a critical food source for American Goldfinches, Common Redpolls, Pine Siskins, and other small finches that cling to the catkins and pry out seeds in the cold months.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Betula occidentalis |

| Family | Betulaceae (Birch) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree / Large Shrub |

| Mature Height | 5–20 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | High (Riparian / Wet Areas) |

| Bloom Time | March – May (early spring, before leaf-out) |

| Flower Type | Wind-pollinated catkins (male drooping, female erect) |

| Fall Color | Golden-yellow |

| Bark | Reddish-brown to bronze with pale horizontal lenticels |

| Soil Type | Moist to wet; streamside alluvials, gravelly loams |

| Wildlife Value | Exceptional — seeds, cover, beaver food, songbird habitat |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–7 |

Native Range

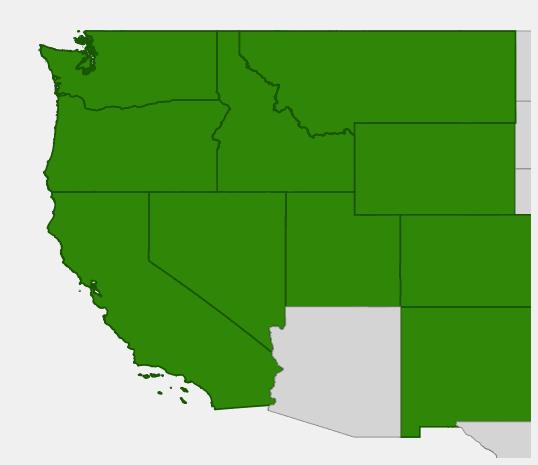

Water Birch has one of the broadest distributions of any western riparian tree, ranging from Alaska and the Yukon south through British Columbia and Alberta to western Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, and California, and east into the Dakotas and Nebraska along major river systems. It is the most widespread and common birch of the Rocky Mountain and Intermountain West regions, filling the ecological role in mountain stream corridors that Paper Birch occupies further north and east.

Throughout its range, Water Birch is almost always found in close association with permanent or semi-permanent water: along streams, rivers, lake margins, seeps, and wet meadow edges. It is a classic riparian obligate, meaning it naturally occurs almost exclusively in or near wetland and streamside habitats. It is most abundant and diverse in the montane zone (roughly 3,000–8,000 feet elevation), where it forms extensive gallery forests and shrub thickets along mountain streams. At lower elevations along larger rivers, it may mix with Cottonwoods and Willows; at higher elevations, it often forms the primary woody vegetation in otherwise treeless alpine meadow stream corridors.

Water Birch is highly cold-tolerant, surviving winters in Alaska and the Canadian Rockies where temperatures regularly drop to -30°F or below. This exceptional cold-hardiness, combined with its moisture requirements, makes it perfectly suited to the high-elevation intermountain valleys where cold air pools and streams remain productive year-round. The species hybridizes naturally with Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera) where their ranges overlap in northern areas.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Water Birch: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Water Birch is an excellent choice for wet garden sites, rain gardens, bioswales, and naturalistic riparian plantings throughout the Rocky Mountain and Intermountain West. Once established in a consistently moist site, it is a vigorous, low-maintenance tree that rewards growers with beautiful winter bark, reliable fall color, and exceptional wildlife value.

Light

Water Birch grows best in full sun to partial shade. It performs best and shows the most vivid bark coloration in open, sunny exposures with at least 4–6 hours of direct sun daily. In full shade, growth is slower and the tree becomes more open-branched. Unlike many birch species, Water Birch tolerates a surprising degree of shade, especially when young — a reflection of its natural occurrence in canyon bottoms and along streams where surrounding terrain limits direct sunlight.

Soil & Water

Water Birch’s defining cultural requirement is consistent moisture. Plant it where soil remains moist to wet throughout the growing season: beside ponds, along streams, in rain garden basins, at the base of slopes where runoff concentrates, or in low areas with seasonally high water tables. It tolerates standing water for extended periods and can even grow in areas that are flooded in spring. In dry sites or during drought, Water Birch will stress, become susceptible to bronze birch borer, and eventually die. Soil type is relatively flexible — it grows in gravelly alluvials, clay, sandy loam, and organic-rich soils — as long as moisture is reliable. Soil pH 5.5–7.5 is acceptable.

Planting Tips

Plant Water Birch in spring or fall from container stock. Choose a site with reliable soil moisture and sun. Space individual plants 10–15 feet apart for a natural grove; for a dense screen or riparian restoration, plant 6–8 feet apart. Water Birch naturally forms multi-stemmed clumps — if a single-trunk tree form is desired, select and maintain one dominant stem while removing competing sprouts during the first few years. Mulch the root zone generously (3–4 inches) to conserve moisture and moderate root temperatures. Keep mulch away from the trunk base to prevent rot.

Pruning & Maintenance

Minimal pruning is needed for Water Birch. Prune in late summer or early fall — NOT in spring, when birches “bleed” (lose large amounts of sap) heavily if cut. Remove dead, crossing, or crowded stems as needed to maintain an attractive multi-stemmed form. The tree is naturally resistant to most pests and diseases when grown in appropriate moist conditions. Bronze birch borer (Agrilus anxius) can attack water-stressed trees — the best prevention is keeping the tree consistently moist. In wet, well-sited conditions, Water Birch is remarkably long-lived and self-sufficient.

Landscape Uses

Water Birch excels in wet and riparian garden settings:

- Rain gardens and bioswales — thrives in the wet-dry cycles these features create

- Stream and pond edges — stabilizes banks and cools water naturally

- Riparian restoration — a keystone species for western stream restoration projects

- Winter interest — glowing reddish-bronze bark is spectacular against snow

- Wildlife habitat — seeds, cover, and nesting structure for birds

- Screen or hedge — fast-growing, dense, and attractive in moist locations

- Four-season ornamental — catkins in spring, green in summer, gold in fall, bronze in winter

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Water Birch is one of the most ecologically valuable trees in the riparian systems of the Rocky Mountain and Intermountain West. Its combination of food production, physical structure, and stream-cooling shade makes it an essential element of healthy western stream ecosystems.

For Birds

The tiny winged seeds of Water Birch are critically important food for several finch species that depend on birch catkins through fall and winter. Common Redpolls, Pine Siskins, American Goldfinches, and Cassin’s Finches cling to the catkins and extract seeds even in deep snow conditions. The dense, multi-stemmed structure of Water Birch thickets provides ideal nesting habitat for Yellow Warblers, Song Sparrows, Willow Flycatchers, and Common Yellowthroats — all of which are closely associated with streamside shrub habitat in the West. Insectivorous birds benefit from the rich invertebrate community that Water Birch foliage supports.

For Mammals

Beavers are the most prominent mammal consumers of Water Birch. Where beavers are active, Water Birch is a primary construction and food material — beavers fell birch stems for dam and lodge construction and cache the branches underwater for winter food. Beaver activity in turn creates wetland habitat that benefits dozens of other species, making Water Birch an indirect ecological keystone. Mule Deer, Elk, and Moose browse the stems and leaves, while small mammals including voles, muskrats, and porcupines consume the bark and inner cambium. The dense thickets provide critical thermal and security cover for deer and elk, particularly in winter.

For Pollinators

Like all birches, Water Birch is primarily wind-pollinated. However, its early-spring catkins provide an important early pollen source for native bees emerging on warm winter days — a resource of particular value in mountain environments where early spring bloom is limited. The moist, shaded stream microhabitat that Water Birch helps create also supports a diverse community of moisture-loving wildflowers and associated pollinators.

Ecosystem Role

Water Birch plays multiple essential roles in western stream ecosystems. Its root systems stabilize stream banks, reducing erosion and preventing sedimentation that would otherwise degrade aquatic habitat. The canopy shades stream water, reducing summer temperatures by several degrees — critical for coldwater fish species like trout and salmon whose eggs and juveniles are highly sensitive to thermal stress. Leaf litter from Water Birch decomposes rapidly, fueling the aquatic invertebrate communities that form the base of stream food webs. The tree’s seed production and early-spring catkin pollen support overwintering and early-season wildlife during the most food-scarce period of the year.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Water Birch has a long history of use by the Indigenous peoples of western North America, though its smaller size and relative scarcity of large individual trunks limited the monumental uses (such as canoe construction) for which Paper Birch was famous in eastern North America. The Shoshone, Ute, Nez Perce, and other peoples of the Intermountain West used Water Birch bark for containers, baskets, and small waterproof vessels. The flexible young stems were woven into baskets and used for cordage. The bark’s tannins made it useful in preserving animal hides.

Medicinally, Water Birch shared many properties attributed to other birch species across cultures. Birch sap, tapped in early spring before leaf-out, was consumed as a tonic and mild diuretic. Tea brewed from the leaves and inner bark served as a treatment for fevers, joint pain, and urinary tract problems — applications consistent with the anti-inflammatory and diuretic compounds (including betulin and methyl salicylate) known from birch chemistry. The Blackfeet and other northern Plains peoples used birch bark as an emergency food source by scraping and consuming the nutritious inner cambium during winter food shortages.

For contemporary restoration ecologists and land managers, Water Birch is among the most valuable and versatile plants in the western riparian toolkit. It establishes readily from live stakes (dormant cut stems planted directly in moist streamside soils), propagates easily from seed, and can be transplanted successfully from container stock. In stream restoration projects, it is often planted in combination with willows, alders, and cottonwoods to reconstruct the full complexity of native riparian plant communities. Its role in cooling streams, stabilizing banks, and feeding wildlife cannot be overstated for the health of western aquatic ecosystems.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does Water Birch have white bark like other birch trees?

No — Water Birch is distinguished from most other birches by its dark reddish-brown to bronze bark with white or cream horizontal lenticels, rather than the peeling white bark of Paper Birch or River Birch. This dark, warm-colored bark is actually one of Water Birch’s most attractive ornamental features, especially in winter when it glows against snow. The bark does not peel in papery sheets like Paper Birch.

Can Water Birch grow in standing water?

Yes — Water Birch is highly tolerant of seasonally saturated and even temporarily flooded soils. It naturally grows along stream margins where spring flooding is common. However, it should not be planted in permanently flooded areas (such as open pond water) as sustained inundation will eventually kill the roots. Wet soil, periodic flooding, and consistently moist conditions are all acceptable. What it cannot tolerate is drought.

Is Water Birch susceptible to bronze birch borer?

Bronze birch borer (Agrilus anxius) can attack Water Birch, as it does most birch species, but healthy trees growing in appropriate moist conditions are far less vulnerable than stressed trees. The best prevention is siting — plant Water Birch only where soil moisture is reliable. Avoid hot, dry sites where the tree will struggle. In native riparian plantings, properly sited Water Birch rarely experiences serious borer issues.

How fast does Water Birch grow?

Water Birch has a moderate growth rate, typically adding 1.5–3 feet per year in good conditions (moist soil, full sun). Growth is faster in the first few years after establishment and in rich, moist alluvial soils. In drier or shadier conditions, growth rate drops substantially. Planted from container stock, it can reach 8–10 feet within 3–4 years in ideal conditions.

Can I use Water Birch for erosion control along a stream?

Absolutely — Water Birch is one of the best native plants for streambank stabilization in western mountain regions. Its dense multi-stemmed form and fibrous root system grip soil effectively. For rapid establishment, plant live stakes (dormant 12–18 inch stem cuttings) directly into moist streambank soil in late fall or early spring, before leaf-out. These often root and leaf out by the first growing season, establishing a root network quickly.