Chinquapin (Castanea pumila)

Castanea pumila, commonly known as Chinquapin, Dwarf Chestnut, or Allegheny Chinquapin, is a remarkable native member of the beech family (Fagaceae) that represents one of the most ecologically and historically important nut-producing trees of the southeastern United States. This resilient small tree or large shrub, typically reaching 20 to 25 feet in height, carries the genetic legacy of the American chestnut without the devastating susceptibility to chestnut blight that destroyed its larger cousin. With its glossy, serrated leaves, fragrant summer flowers, and protein-rich nuts enclosed in spiny burs, Chinquapin has sustained both wildlife and human populations across the Southeast for thousands of years.

The species produces some of the most intensely fragrant flowers in the eastern forest — slender spikes of strongly scented staminate flowers that can perfume entire woodland areas during their June and July blooming period. These cream-colored catkins, reaching 4 to 6 inches long, create a striking visual display against the tree’s deep green foliage while attracting numerous pollinators and beneficial insects. The resulting nuts, though smaller than those of American chestnut, are exceptionally sweet and have been described as among the finest wild foods available in North America.

Beyond its value as a food source, Chinquapin serves as a cornerstone species in southeastern ecosystems, supporting an incredible diversity of wildlife from songbirds and game birds to mammals ranging from squirrels to black bears. Its ability to thrive in poor soils, tolerate drought, and resprout vigorously after cutting or fire makes it invaluable for ecological restoration, wildlife habitat improvement, and sustainable forestry practices. For gardeners and land managers seeking a native tree that combines beauty, ecological function, and practical benefits, Chinquapin offers an unmatched combination of attributes wrapped in a compact, manageable size perfect for smaller properties and urban landscapes.

Identification

Chinquapin typically grows as a small tree or large multi-stemmed shrub, reaching 20 to 25 feet in height with a trunk diameter of 6 to 10 inches, though exceptional specimens can occasionally reach 30 feet tall and 18 inches in diameter. The growth form is quite variable, ranging from single-trunked small trees to dense, thicket-forming shrubs with multiple stems arising from a common base. This variability often depends on growing conditions, management history, and genetic variation among populations.

Bark

Young Chinquapin bark is smooth and gray-brown, becoming slightly furrowed with age into shallow, narrow ridges. The bark remains relatively smooth compared to many other trees, never developing the deeply plated appearance of mature oaks or the shaggy texture of older hickories. On older trunks, the bark develops a slightly scaly texture with thin, flat plates that may curl at the edges. The inner bark is reddish-brown and contains tannins, though in lower concentrations than many other members of the beech family.

Leaves

The leaves are perhaps Chinquapin’s most distinctive vegetative feature — simple, alternate, and oblong-lanceolate (elongated with a narrow oval shape), measuring 3 to 5 inches long and 1 to 2 inches wide. Each leaf has a prominent midrib and 15 to 20 pairs of straight, parallel veins that extend to sharp, forward-pointing teeth along the margins. The upper surface is lustrous dark green and smooth, while the underside is paler and may have fine hairs, particularly along the veins.

Fresh leaves have a distinctive appearance that helps separate Chinquapin from similar species — the teeth are sharp and uniform, and the leaf base is typically rounded to slightly heart-shaped. In autumn, the foliage turns yellow-brown before dropping, though some leaves may persist into early winter in protected locations.

Flowers

Chinquapin flowers appear from June through July in one of the most spectacular floral displays of any southeastern tree. The species is monoecious, producing both male and female flowers on the same plant. Male flowers are arranged in slender, cream-colored catkins (aments) that can reach 4 to 6 inches long, emerging from the leaf axils and hanging conspicuously from the branches. These catkins produce clouds of pollen and emit an intensely sweet, somewhat musky fragrance that can be detected from considerable distances.

Female flowers are much smaller and less conspicuous, appearing as tiny structures at the base of some male catkins or occasionally on separate short spikes. After pollination, these develop into the characteristic spiny burs that enclose the developing nuts.

Fruit & Nuts

The fruit of Chinquapin consists of spiny burs approximately ¾ to 1 inch in diameter, much smaller than those of American chestnut but with similarly sharp spines. Each bur typically contains a single nut (occasionally two), which is glossy brown when mature, roughly ½ inch in diameter, and notably sweet and flavorful. The nuts ripen in September and October, with the burs splitting open to release them. Fresh nuts are excellent eating — sweet, starchy, and lacking the astringency found in acorns and some other wild nuts.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Castanea pumila |

| Family | Fagaceae (Beech) |

| Plant Type | Small Deciduous Tree / Large Shrub |

| Mature Height | 20–25 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | June – July |

| Flower Color | Cream-colored |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 5–9 |

Native Range

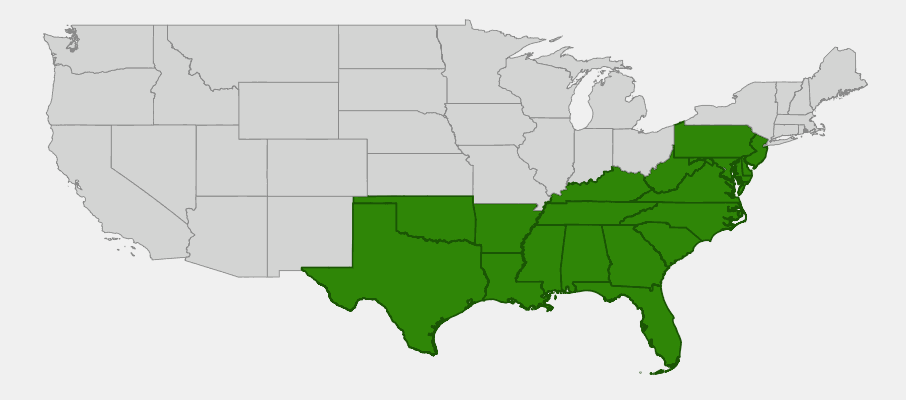

Chinquapin has one of the broadest natural distributions of any native chestnut species, ranging from southern Pennsylvania and New Jersey south to central Florida and west to eastern Texas, Oklahoma, and southeastern Arkansas. The species is most abundant in the southeastern Coastal Plain and Piedmont regions, but extends into the southern Appalachian Mountains and occurs sporadically in suitable habitats throughout much of the eastern United States. This extensive range reflects Chinquapin’s adaptability to diverse soil types, moisture regimes, and climatic conditions.

Within this range, Chinquapin occupies a remarkable variety of habitats, from dry, sandy soils of pine forests to rich bottomlands and mountain slopes. It is particularly common in oak-hickory forests, pine-oak woodlands, and forest edges, often forming dense thickets in areas that have been disturbed by logging, fire, or other disturbances. The species shows excellent tolerance for poor soils and can thrive on sites too dry or nutrient-poor for many other hardwood trees.

Historically, Chinquapin was even more widespread and abundant than it is today. Like many native nut-producing trees, its populations have been reduced by habitat conversion, fire suppression, and in some areas, overcollection of nuts. However, the species has shown remarkable resilience and continues to maintain stable populations throughout most of its range. Its ability to resprout vigorously from cut stumps and spread by root suckers has helped it persist even in areas with intensive land management.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Chinquapin: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Chinquapin is one of the most adaptable and low-maintenance native trees available, thriving in a wide range of conditions with minimal care once established. Its natural resilience and tolerance for challenging sites make it an excellent choice for both novice and experienced gardeners.

Light

Chinquapin grows well in full sun to partial shade, with full sun generally producing the most prolific flowering and nut production. The species can tolerate quite dense shade, though growth will be slower and flowering reduced. In forest edges and partially shaded locations, Chinquapin often develops an attractive, somewhat open growth habit that works well in naturalistic landscapes. For maximum nut production, choose a location with at least 6 hours of direct sunlight daily.

Soil & Water

One of Chinquapin’s greatest strengths is its adaptability to diverse soil conditions. The species thrives in everything from sandy, well-drained soils to heavier clay, though it performs best in moderately well-drained sites. It shows excellent tolerance for acidic soils (pH 4.5-6.5) and can handle periodic drought once established. While Chinquapin can grow in poor, nutrient-deficient soils where many other trees struggle, it responds well to organic matter and will grow more vigorously in richer soils.

Planting Tips

Plant Chinquapin in spring or fall when temperatures are moderate. The species transplants easily from containers and establishes quickly. Space plants 15-20 feet apart for single specimens, or 8-12 feet apart if creating a thicket or screen. When planting, dig a hole as deep as the root ball and twice as wide, backfilling with native soil. Water thoroughly after planting and maintain consistent moisture through the first growing season. Mulching around the base helps retain moisture and suppress weeds.

Pruning & Maintenance

Chinquapin requires minimal pruning in most landscape situations. If training as a single-trunked tree, remove competing stems and lower branches during the dormant season. For thicket management, selective removal of older stems every few years encourages fresh growth and maintains vigor. The species responds well to coppicing (cutting to ground level) and will resprout vigorously if renewal is desired. Remove dead or damaged wood as needed, and thin overcrowded stems to improve air circulation.

Landscape Uses

Chinquapin’s versatility makes it valuable for numerous landscape applications:

- Wildlife gardens — exceptional value for birds, mammals, and pollinators

- Edible landscapes — produces delicious, nutritious nuts

- Natural screens — forms dense thickets when allowed to sucker

- Erosion control — excellent for slopes and challenging sites

- Pollinator habitat — intensely fragrant flowers attract beneficial insects

- Restoration projects — helps establish native plant communities

- Urban forestry — tolerates pollution and urban conditions

- Specimen planting — attractive form and seasonal interest

Nut Production & Harvesting

For optimal nut production, plant multiple Chinquapins to ensure cross-pollination, though single trees often produce some nuts through self-pollination. Trees typically begin producing nuts 3-5 years after planting, with production increasing as they mature. Harvest nuts in fall when burs split open naturally — fresh nuts are best eaten immediately or can be stored briefly in the refrigerator. For longer storage, nuts can be dried or processed into flour.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Few native trees match Chinquapin’s ecological importance, supporting an extraordinary diversity of wildlife species while contributing significantly to forest ecosystem health and resilience.

For Birds

Chinquapin nuts are consumed by numerous bird species, including Wild Turkey, Northern Bobwhite, Wood Ducks, Blue Jays, American Crows, and various woodpecker species. The dense branching structure provides excellent nesting habitat for songbirds, while the abundant insects attracted to the flowers support insectivorous species during the critical breeding season. Ruffed Grouse, where their ranges overlap, consume both nuts and foliage. The tree’s tendency to form thickets creates ideal cover for ground-nesting birds and provides thermal protection during harsh weather.

For Mammals

Chinquapin nuts are among the most important food sources for southeastern wildlife. White-tailed Deer consume nuts, foliage, and young twigs, while Black Bears rely heavily on Chinquapin nuts during fall months to build fat reserves for winter. Gray Squirrels, Fox Squirrels, and Flying Squirrels cache nuts for winter storage and depend on them as a primary protein source. Chipmunks collect and store vast quantities of nuts in their burrow systems. Raccoons, Opossums, and various mice species also consume the nuts when available.

For Pollinators

The intensely fragrant flowers attract an incredible diversity of pollinators and beneficial insects. Native bees, including bumble bees, carpenter bees, and various specialist species, visit the flowers for pollen and nectar. Beneficial wasps, beetles, and flies are drawn to the blooms, creating a complex web of insect activity that supports predatory species and improves overall garden health. The long flowering period provides consistent nectar sources during the often challenging mid-summer period when few other trees are blooming.

Ecosystem Role

As a member of the beech family, Chinquapin plays a crucial role in southeastern forest ecosystems. Its ability to fix nitrogen through mycorrhizal associations improves soil fertility for neighboring plants. The species’ vigorous resprouting after disturbance makes it valuable for forest regeneration and succession. Chinquapin’s deep taproot helps access groundwater during droughts while its extensive surface root system aids in soil stabilization and erosion control. The fallen nuts and leaves contribute significant organic matter to forest soils, supporting decomposer organisms and nutrient cycling.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Chinquapin holds a distinguished place in the cultural history of the southeastern United States, serving as an important food source and cultural touchstone for Indigenous peoples long before European contact. Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, and numerous other tribes incorporated Chinquapin nuts into their seasonal food systems, often traveling considerable distances to harvest from productive groves during the fall nut season. The nuts were eaten fresh, dried for winter storage, or ground into nutritious flour for bread-making. Some tribes used Chinquapin leaves and bark medicinally, though specific applications varied among different cultural groups.

European colonists quickly adopted Chinquapin as both food and medicine, often learning harvesting techniques and preparation methods from Indigenous peoples. The nuts became an important supplement to colonial diets, particularly in frontier areas where traditional European foods were scarce. Children often gathered Chinquapins as both snacks and trade items, and the nuts were sometimes sold in local markets alongside other wild foods. Folk medicine traditions attributed various healing properties to different parts of the plant, though these uses were generally less sophisticated than traditional Indigenous applications.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Chinquapin played important roles in rural southern economies and foodways. Families often had favorite collecting areas that were passed down through generations, and the annual nut harvest became a significant social and economic event in many communities. The nuts were used fresh, dried, or ground into meal for winter cooking. Some entrepreneurs established small businesses processing Chinquapin flour, and the nuts were occasionally shipped to urban markets where they commanded premium prices.

The wood of Chinquapin, while not as valuable as that of American chestnut, found various uses in local construction and crafts. Its resistance to decay made it suitable for fence posts, while the straight grain was valued for tool handles and small woodworking projects. The bark was sometimes used for tanning leather, though it contained lower levels of tannins than oak bark. Today, Chinquapin is increasingly valued for its ecological restoration potential and as a sustainable source of nutritious wild food, with renewed interest in traditional foodways driving efforts to restore and expand natural populations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Chinquapin nuts safe to eat?

Yes, Chinquapin nuts are not only safe but are considered among the finest wild nuts in North America. They can be eaten raw or cooked and have a sweet, starchy flavor without the bitterness found in acorns. However, like all wild foods, they should be properly identified and collected only from clean, uncontaminated areas.

How long do Chinquapin nuts keep?

Fresh nuts are best eaten within a few days of collection, though they can be stored in the refrigerator for several weeks. For longer storage, nuts can be dried in a warm, well-ventilated area and stored in airtight containers for several months. Properly dried nuts can also be ground into flour for cooking.

Will Chinquapin get chestnut blight?

Chinquapin shows significantly better resistance to chestnut blight than American chestnut, though it is not completely immune. Many trees can survive infection and continue to produce nuts, making it a more reliable choice for landscapes and restoration projects where chestnut blight is present.

Can I grow Chinquapin from nuts?

Yes, fresh nuts germinate readily if planted immediately after collection in fall. Plant nuts about 1 inch deep in well-drained soil and protect from rodents. Germination typically occurs the following spring. Stored nuts may require cold stratification over winter to break dormancy.

How can I encourage more nut production?

Plant multiple Chinquapins to ensure cross-pollination, provide full sun conditions, and maintain adequate soil moisture. Regular pruning to remove dead wood and thin overcrowded branches can also improve flowering and nut production. Be patient — young trees typically begin serious production around 5-7 years of age.

Looking for a nursery that carries Chinquapin?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina