Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra)

Rhus glabra, commonly known as Smooth Sumac, stands as one of North America’s most adaptable and ecologically valuable native shrubs, providing spectacular seasonal color and essential wildlife habitat across an remarkably diverse range of habitats from coast to coast. This fast-growing member of the Anacardiaceae (sumac) family distinguishes itself from its relatives through its completely smooth, hairless stems and leaf stalks — a characteristic reflected in its species name “glabra,” meaning smooth or hairless. Unlike some of its notorious cousins in the cashew family, Smooth Sumac is completely non-toxic and safe to handle, making it an excellent choice for landscapes where children and pets are present.

The shrub’s remarkable adaptability becomes evident in its native range, which spans virtually the entire continental United States and extends into southern Canada — one of the widest distributions of any North American woody plant. From the rocky soils of New England hillsides to the clay prairies of Texas, from the sandy shores of the Great Lakes to the volcanic slopes of the Pacific Northwest, Smooth Sumac has proven its ability to thrive in conditions that challenge most other native plants. This ecological versatility stems from its deep taproot system, which can extend 6-10 feet into the soil to access deep moisture, and its ability to fix nitrogen through specialized root bacteria, allowing it to improve poor soils as it grows.

Perhaps no native shrub provides more dramatic fall color than Smooth Sumac, whose compound leaves transform into brilliant displays of scarlet, orange, and yellow that can be visible from miles away. These stunning autumn colors, combined with the persistent clusters of fuzzy red berries (technically drupes) that crown each female plant, create landscape focal points that rival any exotic ornamental. The berries themselves are not merely decorative — they provide crucial winter food for over 100 species of birds and numerous mammals, while the dense thickets formed by the shrub’s spreading root system offer essential nesting sites and thermal cover for wildlife throughout the year.

The cultural history of Smooth Sumac is equally rich, with Indigenous peoples of North America utilizing virtually every part of the plant for centuries. The tart, vitamin C-rich berries were (and still are) used to create refreshing beverages similar to pink lemonade, while various parts of the plant provided materials for traditional medicines, dyes, and even tobacco substitutes. The inner bark was used for tanning leather, and the hollow stems served as pipe stems and beads. In modern ecological restoration, Smooth Sumac serves as a “pioneer species” that quickly colonizes disturbed soils, prevents erosion, and creates conditions favorable for the establishment of later-successional forest trees — making it invaluable for healing damaged landscapes.

Identification

Smooth Sumac presents a bold, architectural presence in the landscape, forming large colonies of upright stems that create distinctive clumps or thickets easily visible from considerable distances. The shrub typically reaches 10-15 feet in height at maturity, though exceptional specimens in ideal conditions may grow to 20 feet or more. The growth habit is strongly colonial — individual plants spread via underground rhizomes to form genetically identical clones that can cover several acres over time. This clonal growth pattern creates the characteristic “sumac groves” that are such familiar features of the North American landscape.

Bark & Stems

The most diagnostic feature for distinguishing Smooth Sumac from its relatives is the complete absence of hairs on all parts of the plant — stems, leaf stalks, and leaf undersurfaces are entirely smooth to the touch. Young stems display attractive reddish-brown to purplish coloration and maintain a glossy, polished appearance. As stems age, they develop a thin, grayish bark that may become slightly furrowed but never develops the thick, corky bark characteristic of tree species.

The internal structure of sumac stems reveals a characteristic white, pithy center that is soft and easily removed. This spongy pith historically made sumac stems valuable for various utilitarian purposes, as the hollow stems could serve as pipe stems, spouts, or even as primitive straws. The wood itself is relatively soft and light, with a yellowish to light brown heartwood surrounding the white sapwood.

Distinctive Compound Leaves

The leaves of Smooth Sumac are pinnately compound — each leaf consists of 11-31 individual leaflets arranged in pairs along a central rachis (leaf stem), with a single terminal leaflet at the tip. The overall leaf length typically ranges from 12-18 inches, creating a bold, tropical appearance that stands out dramatically in temperate landscapes. The rachis itself is smooth and often displays the same reddish coloration as the young stems.

Individual leaflets are lance-shaped to oblong, typically 2-4 inches long and ½-1 inch wide, with distinctly serrated (toothed) margins. The upper surfaces are dark green and glossy, while the undersides are pale green to whitish and completely smooth — this smooth underside distinguishes Smooth Sumac from Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina), whose leaflet undersides are densely fuzzy. The leaflets are arranged alternately along the rachis, and each has a very short petiolule (individual leaflet stem) or may be nearly sessile.

In autumn, Smooth Sumac produces some of the most spectacular fall color of any North American shrub. The transformation typically begins in late August or early September, with individual leaflets turning brilliant shades of scarlet, orange, yellow, and deep red. The color change often progresses from the leaflet tips inward, creating beautiful graduated effects. At peak color, a single sumac grove can appear to be on fire, visible from miles away and serving as a beacon of autumn’s arrival.

Flowers & Fruit Clusters

Smooth Sumac is dioecious — male and female flowers are produced on separate plants. The flowers appear in dense, cone-shaped or pyramidal clusters called panicles at the tips of branches in late spring to early summer. These flower clusters are typically 4-8 inches tall and 3-4 inches wide at the base, standing erect above the foliage canopy.

Male flowers are yellowish-green and relatively inconspicuous, though they produce abundant pollen that can create light clouds when the branches are shaken during peak bloom. Female flowers are similar in color but slightly more compact, and they give rise to the distinctive fruit clusters that make Smooth Sumac so recognizable in the landscape. Each female flower develops into a small drupe (berry-like fruit) covered with short, dense hairs that give the mature fruit clusters their characteristic fuzzy, velvety texture.

The fruit clusters ripen in late summer to early fall, turning from green to brilliant red and persisting on the shrubs throughout winter and often into the following spring. These dense, cone-shaped clusters of red fruits create striking architectural elements in the winter landscape, particularly when dusted with snow. The individual fruits are quite small — typically less than ¼ inch in diameter — but they are packed densely together to create impressive display structures that can measure 6-8 inches tall and 4 inches across at the base.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Rhus glabra |

| Family | Anacardiaceae (Sumac) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 10–15 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low (Drought Tolerant) |

| Bloom Time | May – July |

| Flower Color | Greenish-yellow |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–9 |

Native Range

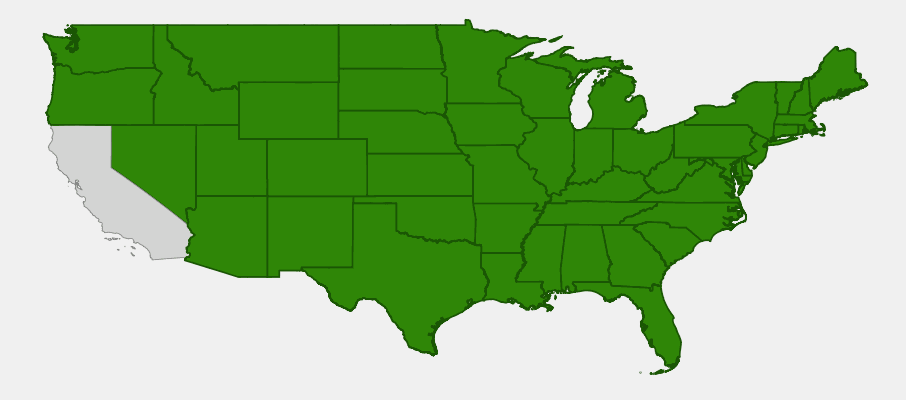

Smooth Sumac boasts one of the most extensive native distributions of any North American woody plant, ranging across virtually the entire continental United States and extending northward into all Canadian provinces except Newfoundland. This remarkable geographic range — from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts and from northern Canada to northern Mexico — testifies to the species’ extraordinary adaptability and ecological versatility. The only areas within this vast range where Smooth Sumac is naturally absent are the most extreme desert regions of the Southwest, the highest mountain peaks, and areas of permanently saturated soils.

This continent-spanning distribution encompasses virtually every major North American ecoregion, from the boreal forests of Canada through the eastern deciduous forests, the Great Plains grasslands, the Rocky Mountain foothills, and the oak woodlands of California. In each of these diverse environments, Smooth Sumac has found its niche, typically colonizing disturbed areas, woodland edges, and sites with well-drained soils where competition from other woody plants is reduced. The species’ ability to thrive in such diverse conditions stems from its remarkable physiological adaptability, deep taproot system, and capacity for nitrogen fixation through specialized root bacteria.

The ecological role of Smooth Sumac varies somewhat across its range, but everywhere it serves as an important early successional species that helps stabilize soils and create conditions favorable for later forest development. In the eastern deciduous forests, it commonly appears in forest gaps created by windstorms, logging, or other disturbances, rapidly colonizing exposed mineral soil and providing cover for tree seedlings. On the Great Plains, it typically occupies ravines, creek bottoms, and the edges of farm fields, where its spreading root system helps prevent erosion while creating wildlife habitat. In the western mountains, it is often found along streams and in areas recovering from fire or other natural disturbances.

The wide distribution of Smooth Sumac is facilitated by its effective seed dispersal mechanisms. The bright red fruit clusters are consumed by over 100 species of birds, which transport the hard, indigestible seeds over considerable distances before depositing them in their droppings. This bird-mediated dispersal allows Smooth Sumac to quickly colonize suitable habitat across vast geographic areas and has undoubtedly contributed to its success as one of North America’s most widespread native shrubs. The species also spreads locally through its extensive rhizome system, which can extend dozens of feet from the parent plant and send up new shoots wherever soil and light conditions are favorable.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Smooth Sumac: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Successfully cultivating native plants requires understanding their natural habitat preferences and recreating those conditions in garden settings. The key to thriving native plant gardens lies in matching plants to appropriate sites rather than trying to force plants to adapt to unsuitable conditions.

Light Requirements

Smooth Sumac is remarkably adaptable to light conditions, thriving in everything from full sun to partial shade. In full sun locations, the shrub develops a denser, more compact growth habit with maximum fall color intensity and berry production. In partial shade, it tends to grow taller and more open, reaching toward available light sources. This flexibility makes Smooth Sumac valuable for a wide range of garden situations, from open meadow plantings to woodland edge environments.

For maximum ornamental impact, particularly fall color and fruit display, full sun locations are preferred. However, in hot southern climates, some afternoon shade can help prevent heat stress and extend the attractive appearance of the foliage through the summer months. The species’ shade tolerance also makes it useful for naturalizing areas under high-canopied trees where many other shrubs struggle.

Soil & Water Requirements

One of Smooth Sumac’s greatest assets is its ability to thrive in poor soils where many other plants struggle. The species is extremely drought-tolerant once established, thanks to its deep taproot system that can extend 6-10 feet into the soil to access deep moisture reserves. It grows well in sandy, rocky, or clay soils and can tolerate both acidic and alkaline conditions, making it suitable for challenging sites where soil improvement is impractical.

While Smooth Sumac can tolerate poor soils, it will grow larger and more vigorously in better conditions. For fastest establishment and maximum ornamental impact, plant in well-drained soil with moderate fertility. The species cannot tolerate wet feet — avoid planting in areas with poor drainage or seasonal flooding, as this can lead to root rot and plant decline.

The nitrogen-fixing ability of Smooth Sumac’s root system actually improves soil conditions over time, as the specialized bacteria associated with its roots convert atmospheric nitrogen into forms available to other plants. This makes Smooth Sumac valuable for soil improvement in degraded areas and helps explain its success as a pioneer species in disturbed habitats.

Planting & Establishment

The best time for planting most native perennials is early fall, which allows plants to establish strong root systems before the stress of their first summer. Spring planting is also successful but requires more careful attention to watering during the first growing season. When planting, dig holes only as deep as the root ball but 2-3 times as wide to encourage lateral root development.

Space plants according to their mature spread requirements, allowing adequate room for air circulation to prevent disease problems. Water thoroughly after planting and maintain consistent moisture for the first full growing season while plants establish. Mulching is particularly important for newly planted natives, as it moderates soil temperature, conserves moisture, and suppresses weed competition.

Pruning & Maintenance

Native plants generally require less maintenance than non-native alternatives, but some basic care helps ensure optimal performance. Deadheading spent flowers can extend the blooming period and prevent excessive self-seeding, though many gardeners prefer to leave some seed heads for wildlife food and winter interest.

Most herbaceous natives can be cut back in late fall or early spring, though leaving the stems through winter provides seed for birds and overwintering habitat for beneficial insects. Remove any diseased or damaged foliage promptly to prevent disease spread, and divide overcrowded clumps every 3-4 years to maintain vigor.

Landscape Applications

Native plants excel in naturalistic landscape designs that work with natural processes rather than against them. Consider these applications:

- Native plant gardens that recreate regional plant communities

- Rain gardens for managing stormwater runoff

- Pollinator gardens that support local wildlife

- Restoration projects for damaged or degraded sites

- Low-maintenance landscapes that reduce input requirements

- Educational gardens that showcase regional natural heritage

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Native plants form the foundation of healthy ecosystems, providing food, shelter, and habitat complexity that supports biodiversity at multiple levels. Each native plant species has evolved complex relationships with local wildlife over thousands of years, creating irreplaceable ecological connections that cannot be replicated by non-native alternatives.

For Birds

Smooth Sumac ranks among the most valuable native plants for bird wildlife, with the red fruit clusters providing crucial food for over 100 species of birds throughout fall and winter. The high-fat content of sumac berries makes them particularly important during migration periods and harsh winter weather when birds need high-energy foods to maintain body heat and fuel long-distance flights. Game birds including Wild Turkey, Ruffed Grouse, and Ring-necked Pheasant consume both the berries and seeds, while countless songbirds depend on sumac fruits as a dietary staple.

Some of the most important avian consumers of sumac berries include American Robin, Cedar Waxwing, Eastern Bluebird, Northern Mockingbird, Brown Thrasher, and various species of woodpeckers, thrushes, and finches. The persistent nature of the fruit clusters — which can remain on plants well into spring — makes sumac particularly valuable during late winter periods when other food sources become scarce. The berries also remain accessible above snow level, providing crucial resources during harsh winter weather.

Beyond fruit production, the dense thicket growth form of Smooth Sumac provides essential nesting habitat and thermal cover for numerous bird species. The multi-stemmed structure creates ideal nesting sites for birds that prefer shrub habitat, including Gray Catbird, Brown Thrasher, Northern Cardinal, and various sparrow species. The thick, impenetrable nature of mature sumac stands also provides critical escape cover and roosting sites, particularly important during harsh weather or when predators are present.

For Pollinators

The small, greenish flowers of Smooth Sumac may not appear particularly attractive to human eyes, but they are magnets for a diverse array of native pollinators. The flowers produce abundant pollen and nectar in dense, easily accessible clusters that attract numerous species of native bees, including honeybees, bumblebees, sweat bees, and various solitary bee species. The timing of sumac bloom — typically late spring through early summer — coincides with peak activity periods for many native pollinators, making it an important component of pollinator support networks.

Perhaps more significantly, Smooth Sumac serves as a host plant for several species of native moths and butterflies, including the beautiful Red-banded Hairstreak butterfly (Calycopis cecrops) whose larvae feed on sumac foliage. The relationship between sumac and these specialized insects represents the kind of co-evolutionary partnership that is essential for maintaining biodiversity but that is lost when native plants are replaced by non-native alternatives. These specialized insects, in turn, become food sources for birds, spiders, and other components of the food web.

The extended blooming period of Smooth Sumac — flowers can appear over several weeks as different branches come into bloom — provides consistent resources for pollinators throughout the late spring and early summer period. This reliability is particularly important for native bee species that may have short adult lifespans and need access to consistent nectar and pollen sources during their brief reproductive periods. The accessibility of sumac flowers also makes them valuable for smaller pollinator species that cannot reach the nectar in flowers with deep tubes or complex structures.

For Mammals

Native plants support mammalian wildlife through direct food resources, habitat structure, and the complex food webs they create. Even plants that don’t provide obvious mammal foods often support the insects, seeds, and other resources that mammals depend on indirectly.

Smooth Sumac provides important food resources for numerous mammal species, with the berries being consumed by everything from tiny mice to large ungulates. White-tailed deer browse the berries and young twigs, particularly during harsh winter weather when other food sources become scarce. Black bears consume large quantities of sumac berries during fall months as they build fat reserves for winter hibernation, and the high fat content of the berries makes them particularly valuable for this purpose.

Smaller mammals that regularly consume sumac berries include raccoons, opossums, squirrels, and chipmunks, while various species of mice and voles eat both berries and seeds. The dense thicket structure created by sumac colonies provides essential cover and nesting habitat for numerous small mammals, creating the kind of habitat complexity that supports diverse mammalian communities. Cottontail rabbits frequently use sumac thickets for escape cover and thermal protection during extreme weather.

The browse value of Smooth Sumac extends beyond the berries — deer and other ungulates consume the twigs and foliage, particularly young growth that is more tender and nutritious. While heavy browsing can reduce fruit production, moderate levels of mammalian use are compatible with healthy sumac populations and actually help maintain the open structure that promotes vigorous new growth and maximum berry production.

Ecosystem Relationships

The true ecological value of native plants lies not in any single function but in their complex web of relationships with other organisms. Each native plant species has evolved over millennia to fit precisely into local ecosystems, creating relationships that cannot be replicated by non-native alternatives regardless of their ornamental value or practical benefits.

Native plants support far more insect diversity than non-native plants — research by Dr. Douglas Tallamy and others has shown that native plants support 35 times more butterfly and moth species than non-native plants. This insect diversity forms the foundation of food webs that support birds, mammals, amphibians, and other wildlife. The loss of native plants therefore creates cascading effects throughout entire ecosystems, reducing wildlife diversity at multiple trophic levels.

Beyond their direct relationships with animals, native plants play crucial roles in maintaining healthy soil ecosystems. Their root systems, leaf litter, and chemical compounds create soil conditions that support diverse communities of bacteria, fungi, and invertebrates. These soil organisms, in turn, cycle nutrients, improve soil structure, and create the foundation for healthy plant communities. The replacement of native plants with non-native alternatives often disrupts these belowground ecosystems, leading to simplified, less resilient soil communities.

Cultural & Historical Uses

The relationship between North America’s indigenous peoples and their native plants represents thousands of years of accumulated knowledge about sustainable resource use, ecological management, and the medicinal properties of native species. This traditional ecological knowledge provides invaluable insights into plant uses and conservation strategies that remain relevant today.

Smooth Sumac occupies a uniquely important place in the cultural traditions of Native American peoples across its vast range, with virtually every tribe within the plant’s distribution developing sophisticated uses for its various parts. The berries, bark, leaves, and roots of Smooth Sumac provided materials for food, medicine, dyes, and numerous utilitarian purposes, making it one of the most versatile and valuable plants in traditional Native American resource management systems.

Perhaps the most widespread traditional use of Smooth Sumac was the preparation of beverages from the ripe berries, a practice that continues today among many Native American communities and has been adopted by modern foragers and traditional foods enthusiasts. The Ojibwe, Cherokee, Iroquois, and dozens of other tribes developed various methods for processing sumac berries into refreshing drinks rich in vitamin C and organic acids. The typical preparation involved soaking clusters of ripe berries in cold water, then straining and sweetening the resulting liquid to create a tart, pink-colored beverage with a flavor reminiscent of pink lemonade.

The medicinal applications of Smooth Sumac were equally diverse and sophisticated. Cherokee healers used sumac bark preparations to treat diarrhea, dysentery, and other digestive ailments, while root preparations were employed for kidney and bladder problems. The Menominee used sumac bark as a treatment for hemorrhoids and various skin conditions, often combining it with other native plants to create compound remedies. Many tribes prepared sumac leaf teas for treating sore throats, fever, and general illness, taking advantage of the plant’s antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties.

The utilitarian uses of Smooth Sumac were equally important in traditional Native American life. The inner bark provided materials for cordage and basketry, while the hollow stems served as pipe stems, arrow shafts, and even primitive musical instruments. The berries and leaves were used to create various dyes, producing shades of red, yellow, and brown for coloring textiles, basketry materials, and ceremonial items. Some tribes used sumac preparations for tanning leather, taking advantage of the high tannin content in the bark and leaves.

Early European colonists quickly learned about sumac’s value from Native American teachers and adopted many traditional uses into their own survival and resource management strategies. Colonial-era documents frequently mention the use of sumac beverages as a substitute for imported citrus fruits and as a treatment for scurvy during long winters. The plant’s abundant vitamin C content made it particularly valuable in frontier settings where fresh fruits and vegetables were often scarce.

During the 19th century, Smooth Sumac became commercially important for its tannin content, with large quantities of bark and leaves being harvested for use in the leather tanning industry. This commercial exploitation led to the overharvesting of sumac in some regions, though the species’ vigorous growth and ability to resprout from roots prevented serious population declines. The development of synthetic tanning agents eventually reduced commercial pressure on wild sumac populations.

In modern times, there has been renewed interest in traditional sumac uses, driven by the growing movement toward wild foods, traditional skills, and sustainable resource use. Contemporary foragers and traditional foods enthusiasts have revived the practice of making sumac-ade, while herbalists have renewed interest in the plant’s medicinal applications. Modern scientific research has confirmed many of the traditional uses, identifying antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory compounds in various parts of the plant.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I successfully establish this plant in my garden?

Success with native plants begins with site selection — choose a location that matches the plant’s natural habitat preferences for light, soil, and moisture conditions. Plant in early fall when possible to allow root establishment before winter, and maintain consistent moisture during the first growing season. Mulching with organic matter helps retain moisture and suppress weeds while the plant establishes.

When is the best time to plant native species?

Early fall is generally the optimal planting time for most native perennials, as cooler temperatures and increased rainfall reduce transplant stress while allowing plants to develop strong root systems before their first summer. Spring planting is also successful but requires more careful attention to watering during establishment. Avoid planting during the heat of summer unless you can provide intensive care and irrigation.

How long does it take for native plants to become established?

Most native perennials require 2-3 full growing seasons to become fully established, though many will flower in their first or second year. The old saying “first year they sleep, second year they creep, third year they leap” applies well to native plant establishment. Patience during the establishment period is crucial, as native plants are investing energy in developing deep, extensive root systems that will support long-term health and drought tolerance.

Do native plants really require less maintenance than non-native plants?

Once established, native plants typically require significantly less maintenance than non-native alternatives because they are adapted to local climate, soil, and pest conditions. However, they do require some maintenance, particularly during establishment and in garden settings where they may be grown outside their optimal habitat conditions. The key is choosing plants appropriate for your specific site conditions rather than trying to force plants to adapt to unsuitable locations.

Can I grow native plants in formal garden settings?

Absolutely! Many native plants are perfectly suitable for formal gardens and can be incorporated into traditional landscape designs. The key is selecting species that match your design goals and site conditions, then providing appropriate care during establishment. Many native plants actually perform better than non-native alternatives in formal settings because they are better adapted to local growing conditions.

How do I know if a plant is truly native to my area?

True natives are species that evolved in your region prior to European settlement and are genetically adapted to local conditions. Check regional flora guides, native plant society resources, and botanical databases to verify native status. Be aware that plant sellers sometimes use the term “native” loosely, including plants that are native to North America but not necessarily to your specific region. When possible, choose plants that are not just regionally native but are sourced from local genetic stock.

What’s the difference between native plants and cultivars of native plants?

Native plants are the straight species as they exist in wild populations, while cultivars (cultivated varieties) are selected or bred forms that may differ in color, size, bloom time, or other characteristics. While cultivars can be attractive and may have some wildlife value, they often provide less ecological benefit than straight native species and may not be adapted to local conditions. For maximum wildlife and ecological value, choose straight native species when possible.

How do native plants help local wildlife?

Native plants form the foundation of local food webs, supporting far more insect diversity than non-native plants. These insects, in turn, provide food for birds, bats, and other wildlife. Native plants also provide appropriate nesting materials, shelter, and seasonal resources that wildlife have evolved to depend on. The complex relationships between native plants and wildlife cannot be replicated by non-native alternatives, regardless of their beauty or practical benefits.

Looking for a nursery that carries Smooth Sumac?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina