Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

Celtis occidentalis, commonly known as Hackberry, American Hackberry, or Sugar Berry, is a magnificent native deciduous tree that stands as one of North America’s most adaptable and resilient hardwoods. This stately member of the Cannabaceae (hemp) family — closely related to elms — has earned a reputation as the “survivor tree” for its exceptional ability to thrive in challenging conditions where other trees struggle or fail entirely. From city streets to prairie edges, riverbanks to rocky hillsides, Hackberry demonstrates remarkable versatility while providing tremendous ecological and landscape value.

Growing naturally from southern Canada to northern Mexico and from the Atlantic coast to the Rocky Mountains, Hackberry is arguably one of the most underappreciated native trees in North America. Mature specimens can reach 60 to 100 feet tall with distinctive vase-shaped crowns, creating impressive landscape features that rival any exotic ornamental. The tree’s compound leaves turn brilliant yellow in fall, while its small, dark purple drupes feed over 40 species of birds throughout autumn and winter.

What sets Hackberry apart is its incredible tolerance for harsh urban conditions — drought, compacted soil, air pollution, salt spray, extreme temperatures, and neglect. This resilience, combined with its rapid growth rate, excellent wildlife value, and attractive form, makes it an outstanding choice for challenging planting sites where other trees would struggle. Yet despite these remarkable qualities, Hackberry remains relatively uncommon in cultivation, representing a tremendous opportunity for gardeners and landscapers seeking tough, attractive native trees.

Identification

Hackberry is easily identified by its combination of distinctive bark, asymmetrical leaves, and characteristic growth habit. Mature trees develop a recognizable vase-shaped crown with ascending branches and a broad, rounded canopy.

Bark

The bark is perhaps Hackberry’s most distinctive feature. Young trees have smooth, light gray bark, but as the tree matures, the bark develops characteristic corky ridges and warty outgrowths (called “nipple galls”) that give it a unique, bumpy texture. The bark color ranges from light gray to brownish-gray, often with a slight reddish tinge. This warty bark texture is so distinctive that experienced naturalists can identify Hackberry from a distance based on bark alone.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and 3 to 5 inches long with a distinctive asymmetrical base — one side of the leaf base extends further along the petiole than the other. This asymmetrical characteristic is shared with elms, reflecting their close relationship. The leaf margins are serrated above the middle but often entire near the base. The upper surface is dark green and slightly rough, while the underside is paler and smooth. In autumn, the foliage turns a clear, bright yellow.

Flowers & Fruit

Hackberry produces inconspicuous greenish flowers in spring, appearing just as the leaves emerge. The tree is polygamous, with male, female, and perfect flowers often found on the same tree. The flowers are wind-pollinated and easily overlooked.

The fruit is a small drupe, about 1/4 to 1/3 inch in diameter, that matures from green to orange-red to dark purple or nearly black in fall. The fruits have thin flesh surrounding a hard seed and hang from long stalks, making them easily accessible to birds. The taste is mildly sweet, and the fruits are technically edible for humans, though they contain little flesh relative to the large seed.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Celtis occidentalis |

| Family | Cannabaceae (Hemp) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 60–100 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low |

| Bloom Time | April – May |

| Flower Color | Greenish (inconspicuous) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

Native Range

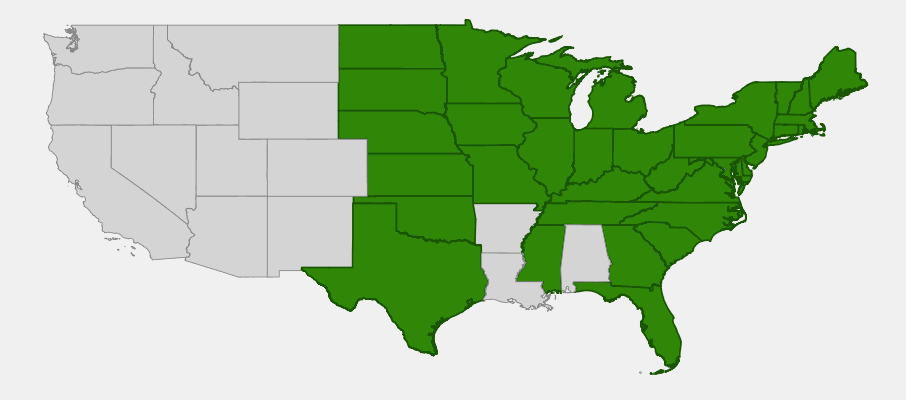

Hackberry enjoys one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American tree, stretching from southern Quebec and Ontario south to northern Florida and west to eastern Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas. This remarkable distribution — spanning virtually the entire eastern two-thirds of the continent — reflects the species’ extraordinary adaptability to diverse climatic conditions and habitat types.

Throughout its native range, Hackberry occupies a wide variety of habitats, from rich bottomland forests and river floodplains to dry upland woods, prairie margins, and limestone bluffs. The species shows particular affinity for disturbed sites and forest edges, often serving as a pioneer tree in abandoned fields and cutover forests. Its ability to thrive in both moist and dry conditions, combined with tolerance for various soil types, has allowed it to colonize habitats ranging from sea level to elevations over 5,000 feet.

In the Great Plains, Hackberry often grows along stream courses and in protected draws, providing crucial shade and wildlife habitat in otherwise treeless landscapes. In eastern forests, it typically occurs as a component of mixed hardwood stands, growing alongside oaks, hickories, maples, and other deciduous trees. The species’ broad ecological amplitude has made it a valuable component of diverse forest ecosystems across its range.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Hackberry: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Hackberry is among the most low-maintenance and adaptable native trees available for landscape use. Its exceptional tolerance for urban conditions, combined with rapid growth and attractive form, makes it an excellent choice for challenging sites where other trees struggle.

Light

Hackberry performs best in full sun but tolerates partial shade reasonably well. In full sun, trees develop the most dense, symmetrical crowns and fastest growth rates. Partially shaded trees may become somewhat open and irregular in form but still make attractive landscape specimens.

Soil & Water

One of Hackberry’s greatest assets is its ability to thrive in a wide range of soil conditions. The tree tolerates everything from rich, moist bottomland soils to dry, rocky, alkaline soils with remarkable equanimity. It grows well in clay, loam, or sandy soils and tolerates both acidic and alkaline pH levels.

Hackberry is extremely drought-tolerant once established, making it ideal for xeriscaping and water-wise landscaping. However, it also tolerates periodic flooding and wet soils, contributing to its reputation as one of North America’s most adaptable trees. Young trees benefit from regular watering during establishment, but mature specimens rarely require supplemental irrigation.

Planting Tips

Plant Hackberry in spring or fall for best establishment. Choose a site with plenty of room for the mature tree’s 40- to 60-foot spread. The tree transplants reasonably well from nursery stock, though container-grown trees tend to establish more successfully than bare-root specimens.

When planting in urban environments, ensure adequate soil volume — at least 700 cubic feet for street trees. Hackberry tolerates compacted soils better than most trees but grows faster and develops better form with adequate root space.

Pruning & Maintenance

Young Hackberry trees benefit from early structural pruning to develop strong scaffold branches and good form. Remove competing leaders and poorly attached branches when the tree is young. Once established, Hackberry requires minimal pruning beyond removal of dead, damaged, or crossing branches.

The tree is generally pest-resistant, though it may occasionally host aphids that produce honeydew. Hackberry nipple galls — small bumps on twigs caused by psyllids — are common but rarely harmful to tree health. Powdery mildew may affect foliage in humid conditions but is typically not serious.

Landscape Uses

Hackberry’s adaptability makes it valuable for many landscape applications:

- Street trees and urban forestry projects

- Shade trees for large residential properties

- Wildlife habitat plantings and bird gardens

- Restoration projects on difficult sites

- Windbreaks and shelterbelts in rural areas

- Parking lot and commercial landscape plantings

- Prairie restoration and savanna reconstruction

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Hackberry provides exceptional wildlife value throughout the year, earning recognition as one of the most important native trees for supporting biodiversity in both natural and urban environments.

For Birds

Over 40 species of birds consume Hackberry fruits, including Northern Flickers, Pileated Woodpeckers, Cedar Waxwings, American Robins, Northern Mockingbirds, and numerous others. The fruits persist on the tree well into winter, providing crucial cold-season food when other sources may be scarce. Game birds including Wild Turkeys, Bobwhite Quail, and Ring-necked Pheasants also eat the fruits and young shoots.

The tree’s dense canopy provides excellent nesting sites for various songbirds, while the strong, flexible branches can support larger nests of hawks and other raptors. The bark’s textured surface harbors insects that attract insectivorous birds throughout the growing season.

For Mammals

Small mammals including squirrels, chipmunks, and mice consume Hackberry fruits, while the dense canopy provides shelter and nesting sites. Deer browse young shoots and foliage, particularly during winter when other food sources are limited.

For Pollinators

While wind-pollinated, Hackberry flowers do attract some small insects early in the season. More importantly, the tree serves as host to several butterfly species, including the Hackberry Emperor (Asterocampa celtis) and Tawny Emperor (A. clyton), whose caterpillars feed exclusively on Hackberry foliage.

Ecosystem Role

As a pioneer species, Hackberry plays crucial roles in forest succession and habitat restoration. Its rapid growth and tolerance for disturbed conditions make it among the first trees to colonize abandoned fields and damaged forests. The tree’s extensive root system helps stabilize soil and prevent erosion, while its leaf litter contributes valuable organic matter to developing soils.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Indigenous peoples across Hackberry’s range recognized and utilized this versatile tree for numerous purposes. Many Plains tribes, including the Comanche, Kiowa, and Pawnee, considered Hackberry fruits an important food source, eating them fresh or grinding them into meal for winter storage. The Dakota called the tree “chanpapa” and valued both the fruits and the inner bark as emergency foods during harsh winters.

The wood, while not as strong as oak or hickory, was valued for specific applications where flexibility and shock resistance were important. Native peoples used Hackberry wood for bent-wood items such as hoops for drums and sweat lodge frames. The wood’s flexibility also made it useful for tool handles, especially for implements that needed to absorb impact.

European settlers found Hackberry wood useful for furniture, boxes, and cooperage, though it was generally considered inferior to harder woods like oak and maple. However, the wood’s light weight and resistance to splitting made it popular for items like yokes and wagon parts where these qualities were advantageous.

Today, Hackberry wood is still occasionally used for furniture, paneling, and dimension lumber, though it remains relatively undervalued commercially. The tree’s greatest modern value lies in its exceptional suitability for urban forestry and landscape applications, where its tolerance for harsh conditions and excellent wildlife value make it an outstanding choice for sustainable landscaping.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Hackberry fruits edible for humans?

Yes, Hackberry fruits are edible and were traditionally eaten by Indigenous peoples. They have a mildly sweet taste but contain little flesh relative to the large seed. The fruits can be eaten fresh or ground into meal, though they’re more valuable left for wildlife than harvested for human consumption.

Why is my Hackberry tree covered in small bumps?

These are likely nipple galls caused by tiny insects called psyllids. While they may look concerning, these galls rarely harm the tree’s health and are a normal part of Hackberry’s ecology. No treatment is necessary, and the galls may actually provide food for birds and beneficial insects.

How fast does Hackberry grow?

Hackberry is a fast-growing tree, typically adding 12 to 18 inches or more per year under favorable conditions. Young trees can grow even faster in rich, moist soils with adequate sunlight. This rapid growth rate makes it excellent for quickly establishing shade or windbreaks.

Is Hackberry related to elm trees?

Hackberry was formerly classified in the elm family (Ulmaceae) and shares several characteristics with elms, including the asymmetrical leaf base. However, recent genetic studies have moved Hackberry to the hemp family (Cannabaceae), reflecting its true evolutionary relationships.

Can Hackberry trees handle urban pollution?

Yes, Hackberry is exceptionally tolerant of urban conditions including air pollution, salt spray, compacted soils, and heat island effects. This tolerance, combined with its rapid growth and excellent wildlife value, makes it one of the best native trees for city environments.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Hackberry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota