Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris)

Matteuccia struthiopteris (syn. Pteretis nodulosa), commonly known as Ostrich Fern, Shuttlecock Fern, or Fiddlehead Fern, is one of North America’s most recognizable and culturally significant ferns. This large, deciduous fern creates dramatic vase-shaped colonies in moist, shaded areas throughout northeastern and north-central regions, where its distinctive fiddleheads have been harvested as a spring delicacy for centuries.

Growing 2 to 6 feet tall with graceful, feather-like fronds that arch outward from a central crown, Ostrich Fern forms some of the most impressive fern displays in the North American landscape. The plant’s common name comes from the resemblance of its sterile fronds to large ostrich plumes, while the tightly coiled fiddleheads that emerge each spring are prized both for their ornamental value and their culinary applications. These early spring shoots, when properly identified and prepared, are considered a gourmet food with a taste often compared to asparagus.

Beyond its fame as an edible wild plant, Ostrich Fern is increasingly valued in shade gardens and naturalistic landscapes for its bold texture, reliable performance, and ability to create lush groundcover in challenging shaded sites. The fern’s tendency to spread via underground rhizomes makes it excellent for naturalizing large areas, while its tolerance for wet soils makes it valuable for rain gardens and areas with poor drainage where many other ornamentals struggle.

Identification

Ostrich Fern is easily distinguished from other native ferns by its large size, vase-shaped growth habit, and the distinctive woolly scales that cover the emerging fiddleheads. The fern produces two distinctly different types of fronds that serve different functions.

Sterile Fronds

The sterile (non-reproductive) fronds are what give Ostrich Fern its dramatic appearance. These large fronds grow 2 to 5 feet tall and up to 12 inches wide, with a classic feather-like shape that tapers toward both the base and tip. The fronds are twice-pinnate, meaning they are divided into pinnae (leaflets), which are further divided into pinnules (sub-leaflets). The rachis (central stem) is deeply grooved and covered with brown, chaffy scales, particularly near the base. These sterile fronds form a distinctive vase or shuttlecock shape, creating the plant’s characteristic silhouette.

Fertile Fronds

The fertile (spore-bearing) fronds are much smaller and completely different in appearance, growing 1 to 2 feet tall in the center of the plant. These specialized fronds are dark brown to black when mature and have a distinctive beaded appearance due to the way the pinnae margins curl over to protect the spore clusters (sori). The fertile fronds appear in late summer and persist through winter, providing an important identification feature even when the sterile fronds have died back.

Fiddleheads

The emerging spring growth, called fiddleheads or crosiers, is perhaps the most distinctive feature of Ostrich Fern. These tightly coiled shoots emerge from the ground in early to mid-spring, covered with brown, papery scales. The fiddleheads are typically 1 to 2 inches in diameter when harvested and have a distinctive groove running along the inside of the emerging rachis. This groove is an important identification feature that helps distinguish edible Ostrich Fern fiddleheads from potentially toxic look-alikes.

Root System

Ostrich Fern spreads by thick, black, branching rhizomes that run horizontally just below the soil surface. These rhizomes produce new crowns (growing points) that develop into individual fern clumps, allowing the plant to form extensive colonies over time. The root system is fibrous and relatively shallow, making it well-adapted to the organic-rich soils of its natural woodland habitat.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Matteuccia struthiopteris (syn. Pteretis nodulosa) |

| Family | Onocleaceae (Sensitive Fern) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Fern |

| Mature Height | 2–6 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Spore Season | Late Summer – Fall |

| Frond Color | Bright Green |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3 – 8 |

Native Range

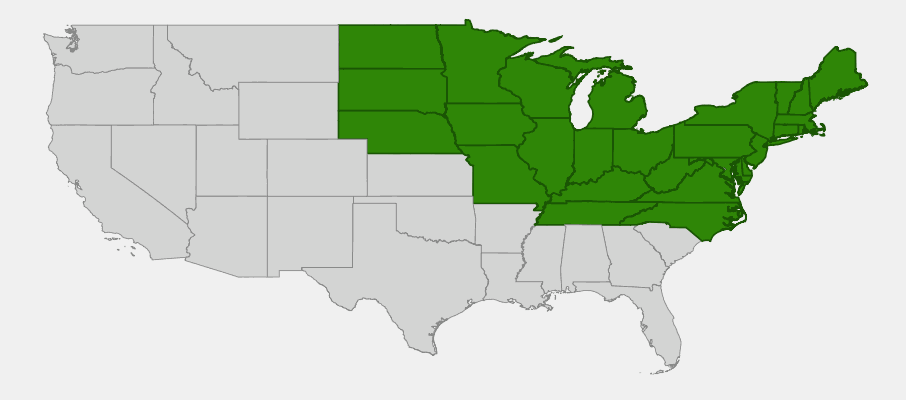

Ostrich Fern has a broad native range across northern and eastern North America, extending from southeastern Canada south to Virginia and North Carolina, and west to the Great Plains states including North Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota. The species is most abundant in the boreal and mixed deciduous forests of the Great Lakes region, New England, and southeastern Canada, where it often forms extensive colonies in suitable habitats.

In its natural environment, Ostrich Fern is typically found in rich, moist soils along streambanks, in floodplains, and in low-lying areas where water collects seasonally. The fern thrives in the deep, organic soils of deciduous and mixed forests, particularly in areas that receive seasonal flooding or have consistently high moisture levels. It is commonly associated with sugar maple, American elm, and other moisture-loving deciduous trees, as well as with other ferns such as Sensitive Fern and Lady Fern.

The species has also been widely cultivated beyond its native range and has naturalized in some areas, particularly in the Pacific Northwest where it escapes from gardens to establish in suitable forest habitats. However, wild harvesting of fiddleheads has put pressure on some populations, and sustainable harvesting practices are important for maintaining healthy wild stands.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Ostrich Fern: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Ostrich Fern is one of the most rewarding native ferns to grow, offering dramatic foliage, easy care, and the bonus of edible fiddleheads in spring. Once established, it requires minimal maintenance while providing maximum visual impact in shaded areas of the landscape.

Light

Ostrich Fern performs best in partial to full shade, mimicking its natural woodland habitat. Morning sun with afternoon shade is ideal, but the plant can tolerate full shade quite well, though growth may be slower and fronds somewhat smaller. Avoid planting in full sun, especially in hot climates, as this can cause fronds to scorch and the plant to struggle. In northern climates with cooler summers, the fern may tolerate more sun if adequate moisture is provided.

Soil & Water

The key to success with Ostrich Fern is providing consistently moist, rich soil that mimics the conditions of its native forest floor habitat. The fern thrives in organic-rich soils with good drainage but consistent moisture availability. Heavy clay soils can work if they don’t become waterlogged, while sandy soils will need regular irrigation and organic matter amendments. The plant is quite tolerant of seasonal flooding and can even grow in areas that are periodically quite wet, making it excellent for rain gardens and low-lying areas where other plants might struggle.

Planting Tips

Plant Ostrich Fern in spring or fall when temperatures are moderate. Space plants 3 to 4 feet apart if planting multiples, keeping in mind that they will spread naturally to form colonies. The fern is excellent for naturalizing large shaded areas where its spreading habit is an advantage rather than a problem. Choose a location protected from strong winds, which can damage the delicate fronds. Adding 2–3 inches of organic mulch helps maintain soil moisture and suppress weeds.

Maintenance & Care

Ostrich Fern is remarkably low-maintenance once established. Cut back the old fronds in late fall or early spring before new fiddleheads emerge, leaving about 2–3 inches of stem base. This cleanup helps prevent disease and makes room for the dramatic spring emergence. The fern may self-seed in suitable conditions, and new plants can also arise from the spreading rhizome system. If the colony becomes too large, excess plants can be dug and transplanted elsewhere in spring or fall.

Landscape Uses

Ostrich Fern’s dramatic size and bold texture make it valuable in numerous garden situations:

- Woodland gardens and shade borders — provides structure and dramatic foliage

- Streamside and pond-edge plantings — thrives in moist conditions

- Rain gardens and bioretention areas — excellent moisture tolerance

- Naturalizing large shaded areas — spreads to form attractive colonies

- Foundation plantings on north sides — tolerates deep shade

- Erosion control on slopes — extensive root system stabilizes soil

- Wildlife habitat gardens — provides cover and structure

- Edible landscapes — fiddleheads are a spring delicacy

Wildlife & Ecological Value

While Ostrich Fern may not provide the nectar and seeds that flowering plants offer, it plays several important ecological roles and provides valuable habitat structure for wildlife.

For Birds

The large, dense fronds of Ostrich Fern provide excellent cover and nesting sites for ground-dwelling and low-nesting birds. The vase-shaped growth form creates protected spaces underneath where birds can forage for insects and seek shelter. Some bird species use the fibrous material from old frond stems as nesting material. The fern’s tendency to form colonies creates particularly valuable habitat corridors for forest birds moving through the landscape.

For Mammals

Small mammals benefit from the cover provided by Ostrich Fern colonies, using the dense growth for protection from predators. Deer occasionally browse on the emerging fiddleheads, though the fern is not a preferred food source. The extensive underground rhizome system provides habitat for various soil-dwelling creatures and helps prevent erosion along streambanks where many animals come to drink.

For Insects & Invertebrates

The decomposing fronds of Ostrich Fern contribute to the rich organic layer of the forest floor, supporting numerous invertebrates including springtails, beetles, and other decomposer organisms. Some insects use the fronds as shelter, and the moist environment created by fern colonies supports various species of snails and other moisture-loving invertebrates.

Ecosystem Role

Ostrich Fern contributes to forest ecosystem health in several ways. Its large fronds intercept rainfall and help moderate soil temperature and moisture levels beneath the canopy. The annual cycle of frond death and decomposition contributes organic matter to the soil, improving soil structure and fertility for the entire forest community. The fern’s ability to thrive in seasonally wet areas makes it valuable for maintaining biodiversity in forest wetlands and along waterways.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Ostrich Fern holds a special place in North American culinary and cultural history, particularly among Indigenous peoples and later European settlers who learned to harvest and prepare the distinctive fiddleheads. The practice of gathering fiddleheads in spring has been passed down through generations and remains an important cultural tradition in many regions, especially in New England, the Maritime Provinces of Canada, and other areas within the fern’s native range.

Indigenous peoples, including the Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, and various Algonquian-speaking nations, have harvested Ostrich Fern fiddleheads for centuries. The tightly coiled shoots were (and still are) gathered in early to mid-spring when they are 3–6 inches tall and the fronds have not yet begun to unfurl. Traditional preparation methods included boiling or steaming the fiddleheads to remove any bitterness and potential toxins, often serving them with fish, game, or other seasonal foods.

When European settlers arrived in North America, they quickly adopted the practice of fiddlehead harvesting from Indigenous peoples. The timing of the harvest—just as winter food stores were running low but before many other wild foods became available—made fiddleheads particularly valuable as a fresh, vitamin-rich spring tonic. This tradition became deeply embedded in the foodways of rural communities throughout the northeastern United States and eastern Canada.

Today, fiddleheads are considered a gourmet delicacy and are commercially harvested in some regions, particularly in Maine and New Brunswick. They are sold fresh in season (typically April through early June, depending on latitude) and are featured in restaurants and farmer’s markets. The taste is often described as a cross between asparagus and green beans, with a slightly nutty flavor. However, proper identification and preparation are critical—only Ostrich Fern fiddleheads are considered safe to eat, and they must be thoroughly cooked before consumption to avoid foodborne illness.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Ostrich Fern fiddleheads safe to eat?

Yes, when properly identified and prepared. Only harvest fiddleheads from confirmed Ostrich Ferns, and always cook them thoroughly by boiling or steaming for at least 10–15 minutes before eating. Never eat raw fiddleheads, and be absolutely certain of your identification—some other fern species can be toxic.

How do I distinguish Ostrich Fern fiddleheads from other ferns?

Look for the distinctive brown, papery scales covering the fiddleheads, the deep groove on the inside of the emerging rachis, and the characteristic vase-shaped growth pattern of mature plants. The fiddleheads should be tightly coiled and relatively large (1–2 inches diameter). When in doubt, consult a knowledgeable forager or botanical guide.

Will Ostrich Fern take over my garden?

Ostrich Fern does spread via rhizomes, but it’s not aggressively invasive in most garden situations. The spreading is gradual and can be managed by removing unwanted shoots. In the right location where you want ground coverage, this spreading habit is actually beneficial.

Can I grow Ostrich Fern in containers?

Yes, but choose a large container (at least 18–24 inches wide and deep) and ensure excellent drainage while maintaining consistent moisture. Container plants will need regular watering and may not achieve the full size of ground-planted specimens. Protect containers from freezing in winter in cold climates.

Why are my Ostrich Fern fronds turning brown?

Brown fronds are normal in fall as the fern enters dormancy. However, if fronds brown during the growing season, this usually indicates insufficient moisture, too much sun exposure, or occasionally fungal issues in very wet conditions. Ensure consistent moisture and proper shade for best results.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Ostrich Fern?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota