Pinkshell Azalea (Rhododendron vaseyi)

Rhododendron vaseyi, commonly known as Pinkshell Azalea, Pink-shell Azalea, or Pink Azalea, is one of North America’s most remarkable and geographically restricted native shrubs. This exceptionally rare member of the Ericaceae (heath) family is endemic to the mountains of western North Carolina, where it grows in only a handful of counties, making it one of the most narrowly distributed rhododendrons in the world. The species was named in honor of George R. Vasey, a botanist who first collected specimens in the late 1800s, and its delicate pink to nearly white flowers have made it a prized horticultural specimen despite its extremely limited natural range.

What makes Pinkshell Azalea truly extraordinary is its breathtaking spring display — masses of soft pink flowers, often with orange or yellow freckles, emerge in April and May before the leaves unfurl, creating a stunning cloud of color against the bare mountain slopes. This deciduous shrub grows 5 to 15 feet tall in its native habitat, forming dense colonies through underground runners in the acidic, well-drained soils of high-elevation forests and heath balds. The flowers, which range from pale pink to nearly white with darker spotting, appear in clusters of 5 to 9 blooms, each with five petals and prominent orange stamens that add to their delicate beauty.

Despite its breathtaking beauty and horticultural value, Pinkshell Azalea remains vulnerable in the wild due to its extremely limited range and habitat specificity. Climate change, development pressure, and collection pressure have all impacted wild populations, making conservation efforts and responsible cultivation increasingly important. For gardeners fortunate enough to obtain nursery-propagated specimens, Pinkshell Azalea offers the rare opportunity to grow one of North America’s most geographically restricted flowering shrubs, bringing a piece of the Southern Appalachian mountains to their landscape while supporting conservation through cultivation.

Identification

Pinkshell Azalea is a deciduous shrub that typically grows 5 to 15 feet (1.5–4.5 m) tall, though exceptional specimens in optimal conditions may reach up to 20 feet. The plant has an upright to spreading growth habit, often forming dense colonies through underground rhizomes and root sprouts, creating impressive natural stands in its native mountain habitat.

Bark & Stems

The bark is thin and smooth on younger stems, becoming slightly rougher with age. Young twigs are green to reddish-brown, often with a slight pubescence (fine hairs) when new, maturing to a gray-brown color. The stems are relatively slender and flexible, allowing the shrub to bend gracefully in mountain winds without breaking. Like all rhododendrons, the wood is hard and fine-grained.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and deciduous, emerging after the flowers in spring. Each leaf is oval to elliptical, 2 to 4 inches (5–10 cm) long and 1 to 2 inches (2.5–5 cm) wide, with a pointed tip and slightly rounded base. The upper surface is medium to dark green and relatively smooth, while the underside is paler and may have fine hairs along the veins. The leaf margins are entire (smooth) or very finely toothed. In autumn, the foliage turns brilliant shades of yellow, orange, and red before dropping, providing a second season of ornamental interest.

Flowers

The flowers are Pinkshell Azalea’s most distinctive and celebrated feature. They appear in terminal clusters of 5 to 9 blooms in April and May, before the leaves emerge — a characteristic that makes the flowering display particularly dramatic. Each flower is funnel-shaped, about 1.5 to 2 inches (4–5 cm) across, with five delicate petals that range from soft pink to nearly white. Most flowers are adorned with distinctive orange, yellow, or red freckles or spots on the upper petal, and all have five prominent stamens with bright orange anthers that extend beyond the petals. The flowers are fragrant, with a sweet, honey-like scent that attracts early-season pollinators.

Fruit & Seeds

The fruit is a dry, woody capsule about ½ to ¾ inch (1.2–1.8 cm) long, containing numerous tiny, winged seeds. The capsules mature in late summer to early fall, splitting open to release the dust-like seeds that are dispersed by wind. In cultivation, most propagation is done through cuttings or division rather than seed, as the tiny seeds require very specific conditions to germinate and establish.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Rhododendron vaseyi |

| Family | Ericaceae (Heath) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 5–15 ft (1.5–4.5 m) |

| Mature Spread | 4–8 ft (1.2–2.4 m) |

| Growth Rate | Slow to Moderate |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Soil Type | Acidic, well-drained, organic |

| Soil pH | 4.5–6.0 (acidic) |

| Bloom Time | April – May |

| Flower Color | Pink to white with orange freckles |

| Fall Color | Yellow, orange, red |

| Fruit | Woody capsules with winged seeds |

| Deer Resistant | Yes |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–7 |

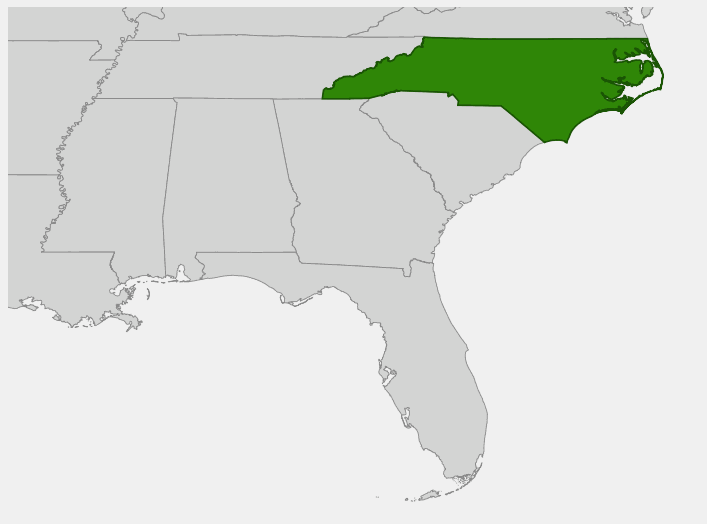

Native Range

Pinkshell Azalea has one of the most restricted natural ranges of any rhododendron species in North America. It is endemic to the mountains of western North Carolina, where it occurs naturally in only a handful of counties including Avery, Burke, Caldwell, McDowell, Mitchell, and Yancey. This extremely narrow distribution makes it one of North Carolina’s most geographically restricted endemic plants and highlights the unique geological and climatic conditions of the Southern Appalachian Mountains.

Within its limited range, Pinkshell Azalea typically grows at elevations between 3,000 and 6,000 feet (900–1,800 m), favoring the acidic, well-drained soils of mountain slopes, heath balds, and gaps in the forest canopy. It is most commonly found in association with other ericaceous shrubs like Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia), Catawba Rhododendron (Rhododendron catawbiense), and various blueberry species (Vaccinium spp.). The species thrives in the cool, moist conditions created by frequent fog and cloud cover at high elevations, where summer temperatures are moderated and winter snow provides additional moisture.

The plant’s habitat is characterized by well-drained, acidic soils derived from granite and gneiss bedrock, often with a thick layer of organic matter from decomposing leaves and other plant material. These “heath bald” communities, where Pinkshell Azalea often grows, are maintained by a combination of factors including fire, ice storms, and the acidic soil conditions that favor ericaceous plants over trees. The species has adapted specifically to these unique conditions, making it challenging to establish outside its native range without careful attention to soil chemistry and microclimate.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Pinkshell Azalea: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Cultivating Pinkshell Azalea requires understanding its very specific native habitat requirements. As an endemic species adapted to the unique conditions of high-elevation Southern Appalachian heath balds, it demands acidic soil, excellent drainage, consistent moisture, and protection from harsh conditions. However, with proper care and attention to these requirements, it can be successfully grown and makes an extraordinary addition to the right garden setting.

Light Requirements

Pinkshell Azalea thrives in part shade to full shade conditions, mimicking its natural habitat on forested mountain slopes where it receives filtered or dappled sunlight. In cultivation, provide morning sun with afternoon shade, particularly in warmer climates. Too much direct sunlight can stress the plant and fade the delicate flower colors, while too little light may reduce flowering. In cooler, northern climates, it can tolerate more sun exposure, but in the southern portions of its hardiness range, consistent shade protection is essential.

Soil & Drainage

Soil requirements are perhaps the most critical factor for successful cultivation. Pinkshell Azalea absolutely requires acidic soil with a pH between 4.5 and 6.0 — preferably on the more acidic end of this range. The soil must be well-drained yet moisture-retentive, rich in organic matter, and loose enough to allow good air circulation around the roots. A mixture of peat moss, aged pine bark, and coarse sand or perlite creates an ideal growing medium. Never plant in clay soil or areas where water stands, as this will quickly kill the plant through root rot.

Water Requirements

Consistent, even moisture is essential, but the soil must never become waterlogged. Water deeply but infrequently, allowing the top inch of soil to dry slightly between waterings. Mulching with 2-3 inches of acidic organic matter (such as pine needles, shredded oak leaves, or aged bark) helps maintain consistent soil moisture and temperature while gradually acidifying the soil as it decomposes. Avoid overhead watering if possible, as wet foliage can promote fungal diseases.

Planting & Establishment

Plant in early spring or fall when temperatures are moderate. Choose a location protected from strong winds and harsh afternoon sun. Dig a planting hole twice as wide as the root ball but no deeper — the top of the root ball should be level with or slightly above the surrounding soil grade to ensure proper drainage. Backfill with an acidic, organic-rich soil mix. Water thoroughly after planting and maintain consistent moisture during the first growing season while the plant establishes.

Fertilizing

Use an acid-loving plant fertilizer specifically formulated for rhododendrons and azaleas, applied according to package directions in early spring before new growth begins. Organic fertilizers like composted pine bark or an acid-forming fertilizer are preferred over synthetic options. Avoid high-nitrogen fertilizers, which can promote excessive vegetative growth at the expense of flowering and may make the plant more susceptible to winter damage.

Pruning & Maintenance

Minimal pruning is needed or desired. Remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late spring after flowering. If light shaping is needed, prune immediately after flowering ends, as flower buds for next year’s display form by midsummer. Never prune in fall or winter, as this removes next year’s flowers. The plant’s natural form is quite attractive and should be preserved whenever possible.

Landscape Uses

Pinkshell Azalea is exceptional for:

- Woodland gardens — naturalized beneath tall trees in filtered shade

- Native plant gardens — as a rare endemic centerpiece species

- Rhododendron and azalea collections — for serious collectors of rare species

- Foundation plantings — on the north or east side of buildings

- Hillside plantings — on well-drained slopes in partial shade

- Spring interest gardens — for spectacular early-season color

- Conservation gardens — helping preserve a rare species through cultivation

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Despite its limited natural range, Pinkshell Azalea plays an important ecological role within its mountain habitat and provides significant value to wildlife, particularly during its spectacular spring blooming period when few other flowers are available at high elevations.

For Pollinators

The early spring flowers of Pinkshell Azalea are crucial for native pollinators emerging from winter dormancy. Native bees, including bumblebees and various solitary bee species, rely heavily on these nectar-rich flowers during a time when few other blooms are available in the mountain environment. The prominent stamens and open flower structure make pollen easily accessible to visiting insects. Butterflies and moths also visit the fragrant flowers, though they are less efficient pollinators than bees for this species.

For Birds

While the flowers themselves don’t directly feed birds, the dense branching structure of mature Pinkshell Azalea provides excellent nesting sites for small songbirds, particularly in the understory environment where it grows. The plant’s tendency to form colonies creates valuable thicket habitat for species like Dark-eyed Juncos, Golden-crowned Kinglets, and various warbler species that breed in high-elevation forests. The woody seed capsules may occasionally be opened by small birds seeking the tiny seeds, though this is not a primary food source.

For Mammals

Large mammals generally avoid browsing Pinkshell Azalea, as rhododendrons contain compounds that are toxic to most mammals. This natural deer resistance is actually beneficial in areas where white-tailed deer populations are high, allowing the plant to flourish without protective measures. Small mammals may occasionally shelter beneath the dense branching structure, particularly during harsh winter weather in its mountain habitat.

Ecosystem Role

Within its native heath bald communities, Pinkshell Azalea contributes to soil stabilization and erosion control through its fibrous root system and tendency to form colonies. The plant’s thick, waxy leaves decompose slowly, contributing to the acidic soil conditions that maintain these unique mountain ecosystems. As an endemic species, it represents a unique genetic resource adapted to the specific conditions of the Southern Appalachian Mountains, making its conservation both ecologically and scientifically important.

The presence of Pinkshell Azalea in a landscape indicates healthy, undisturbed mountain forest conditions with proper soil chemistry and moisture regimes. In cultivation, it serves as an indicator plant for acidic soil conditions and can be used to create habitat gardens that support the specialized wildlife associated with heath communities.

Cultural & Historical Uses

The cultural significance of Pinkshell Azalea is deeply intertwined with the natural and cultural history of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Unlike many widely distributed native plants with extensive ethnobotanical histories, Pinkshell Azalea’s extremely limited range meant that its cultural uses were largely confined to the indigenous peoples and later settlers of western North Carolina’s mountain regions.

The Cherokee Nation, whose ancestral territory encompassed much of western North Carolina including the native range of Pinkshell Azalea, would have been familiar with this spectacular shrub during their centuries of habitation in the region. However, like other rhododendrons, Pinkshell Azalea contains grayanotoxins and other compounds that make it toxic to humans and most animals. This natural toxicity likely limited its use in traditional Cherokee medicine and foodways, unlike many other native plants that became important cultural resources. The Cherokee’s deep knowledge of their plant communities would have certainly included awareness of this rare and beautiful endemic species, though specific traditional uses are not well documented in historical records.

European settlers and early botanists first encountered Pinkshell Azalea in the late 1800s, when George R. Vasey collected specimens that led to its scientific description. The species was named Rhododendron vaseyi in his honor, recognizing his contributions to botanical exploration in the region. Early mountain settlers, many of Scottish and Irish descent, appreciated the plant’s spectacular spring display and sometimes transplanted specimens to their homesteads, though success was often limited due to its specific habitat requirements.

By the early 1900s, Pinkshell Azalea had gained attention in horticultural circles, particularly among wealthy estate owners and plant collectors who prized rare and unusual species. The plant’s extreme rarity and spectacular flowers made it highly sought after, leading to collection pressure on wild populations that continues to be a conservation concern today. Responsible nursery propagation has since reduced pressure on wild plants, though illegal collection still occasionally occurs.

Today, Pinkshell Azalea serves as an important symbol of North Carolina’s unique natural heritage and the biological significance of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. It appears in botanical gardens specializing in native plants and is increasingly featured in conservation education programs that highlight the importance of protecting endemic species and their habitats. The plant has also become a symbol of the delicate balance required to maintain the unique heath bald ecosystems of the region, serving as both a botanical treasure and a reminder of the importance of habitat conservation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is Pinkshell Azalea so rare and hard to find?

Pinkshell Azalea is endemic to just a few counties in western North Carolina, making it one of the most geographically restricted rhododendron species in North America. Its rarity in cultivation stems from both its limited natural range and its very specific growing requirements, including acidic soil, excellent drainage, and specific climate conditions. Additionally, it has been slow to enter commercial propagation due to challenges in cultivation and its protected status in the wild.

Can I grow Pinkshell Azalea outside of North Carolina?

Yes, but success depends on your ability to replicate its native habitat conditions. It can be grown in USDA zones 4-7 with acidic, well-drained soil, consistent moisture, and protection from harsh sun and wind. It’s most successful in areas with naturally acidic soil and moderate summer temperatures. Northern gardeners often have better success than those in warmer southern climates.

How do I make my soil acidic enough for Pinkshell Azalea?

The soil pH needs to be between 4.5-6.0, preferably on the more acidic end. Amend planting areas with peat moss, aged pine bark, and sulfur-based soil acidifiers. Mulch with acidic organic materials like pine needles or oak leaves. Test your soil pH regularly and adjust as needed. In areas with naturally alkaline soil or water, container growing may be more successful than in-ground planting.

When do the flowers appear, and how long do they last?

Pinkshell Azalea blooms in April and May before the leaves emerge, creating a spectacular display of pink to white flowers with orange freckles. The flowering period typically lasts 2-3 weeks, depending on weather conditions. Cool weather extends the bloom time, while hot weather can cause flowers to fade more quickly. The exact timing varies by location, elevation, and yearly weather patterns.

Is it legal to collect Pinkshell Azalea from the wild?

No, collecting wild specimens is both illegal and harmful to this rare species. Pinkshell Azalea is protected in its native range, and removal from public lands is prohibited. Collection from private property requires landowner permission but is still discouraged due to conservation concerns. Always purchase nursery-propagated plants from reputable sources that specialize in native plants and support conservation through ethical propagation practices.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Pinkshell Azalea?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina