Pussy Willow (Salix discolor)

Salix discolor, commonly known as Pussy Willow, American Willow, or Glaucous Willow, is one of North America’s most beloved and recognizable native shrubs, cherished for its distinctive fuzzy catkins that appear as one of spring’s earliest signs. This hardy member of the willow family (Salicaceae) has captivated people for generations with its soft, silvery-gray catkins that emerge on bare branches while winter still grips the landscape, earning it a special place in both wild ecosystems and human culture.

The common name “pussy willow” derives from the resemblance of the male catkins to a cat’s paw — soft, fuzzy, and gray with a silky texture that seems to invite touch. These catkins, botanically known as catkins or aments, are actually clusters of tiny flowers that lack petals and sepals, relying instead on wind for pollination. The timing of their emergence, often coinciding with the first warm days of late winter or early spring, makes them a powerful symbol of renewal and the promise of warmer days ahead.

Growing naturally in wetlands, stream banks, and moist soils across much of northern North America, Pussy Willow demonstrates remarkable adaptability and ecological value. As a fast-growing deciduous shrub or small tree, it provides critical early-season pollen for emerging bees and other insects, while its flexible branches and dense growth habit offer nesting sites and cover for numerous bird species. For modern gardeners and land managers, Pussy Willow offers unique value as both an ornamental plant with four-season interest and a cornerstone species for riparian restoration, bioswale plantings, and wildlife habitat projects.

Identification

Pussy Willow typically grows as a large multi-stemmed shrub or small tree, reaching 15 to 30 feet in height with a spread of 10 to 20 feet at maturity. The plant develops an upright, somewhat irregular crown with a loose, open branching pattern that becomes more pronounced with age. Under optimal conditions in moist soils, it can occasionally reach 40 feet tall, though 20-25 feet is more typical in most landscape settings.

Bark & Stems

The bark on mature trunks is grayish-brown with shallow furrows and a somewhat scaly texture. Young twigs are distinctive, appearing reddish-brown to purplish-brown with a glossy surface when first emerging, later becoming gray-brown as they mature. The twigs are notably flexible — a characteristic shared by many willows — and have a bitter taste if chewed. Winter buds are small, pointed, and covered with a single scale, unlike many other woody plants that have multiple bud scales.

Leaves

The simple leaves are arranged alternately along the branches, measuring 2 to 4 inches long and 1 to 2 inches wide. Each leaf is elliptical to obovate (egg-shaped with the wider end toward the tip) with a pointed apex and finely serrated margins. The upper surface is dark green and smooth, while the underside is distinctly paler, often with a bluish or whitish bloom (glaucous coating) that gives the species its alternate name “Glaucous Willow.” The leaves have prominent veining and short petioles (leaf stems) with small stipules at the base that often drop early in the season.

Catkins & Flowers

Pussy Willow is dioecious, meaning male and female flowers occur on separate plants. The male catkins are the familiar “pussy willows” — dense, oval clusters of tiny flowers covered with silky, silvery-gray hairs that give them their distinctive fuzzy appearance. These male catkins emerge 2 to 4 weeks before the leaves, typically measuring 1 to 2 inches long and ¾ inch wide. As they mature, the catkins elongate and the individual flowers become visible as small yellow stamens emerge from the silvery bracts. Female catkins are less showy, appearing greenish and more slender, eventually developing into elongated clusters of small capsules containing numerous tiny seeds with white, cottony hairs for wind dispersal.

Seasonal Changes

Pussy Willow’s appeal extends through multiple seasons. In late winter to early spring, the fuzzy catkins provide the year’s first major ornamental interest. As spring progresses, the fresh green leaves create an attractive backdrop. Summer brings full, dense foliage that provides excellent screening. In autumn, the leaves turn yellow before dropping, revealing the architectural branching pattern that provides winter interest until the next year’s catkins emerge.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Salix discolor |

| Family | Salicaceae (Willow) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Large Shrub / Small Tree |

| Mature Height | 15–30 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Bloom Time | March – April |

| Flower Color | Silvery-gray (catkins) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–8 |

Native Range

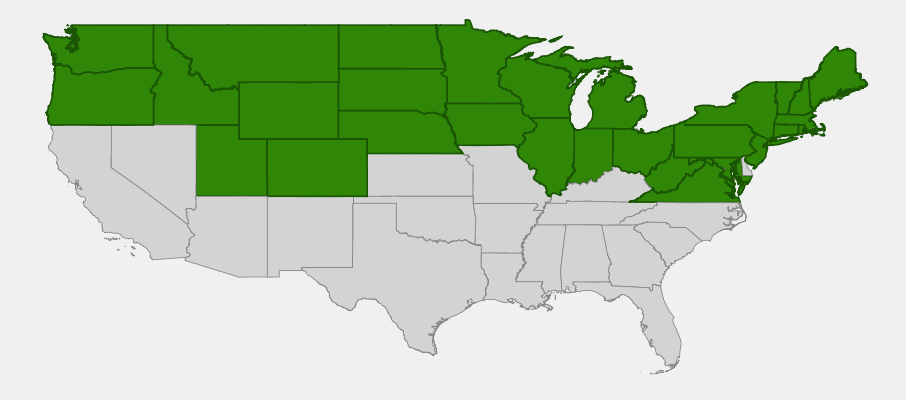

Pussy Willow has a broad native distribution across northern North America, reflecting its preference for cooler climates and abundant moisture. The species ranges from coast to coast across southern Canada and extends south through much of the northern United States, with scattered populations reaching into the mountains of the western states where suitable cool, moist conditions exist. This extensive range has made Pussy Willow an important component of riparian and wetland ecosystems throughout much of temperate North America.

The species reaches its greatest abundance in the Great Lakes region and northeastern United States, where it commonly inhabits stream banks, pond edges, swamps, and other wetland areas. In these regions, Pussy Willow often forms dense colonies through both sexual reproduction and vegetative spread via root suckers, creating important habitat structure in riparian zones. The plant’s tolerance for periodic flooding and its ability to stabilize stream banks with its extensive root system have made it a keystone species in many aquatic ecosystems.

Moving westward, Pussy Willow follows river valleys and mountain watercourses, where it continues to play important ecological roles in riparian forest communities. In the northern Rocky Mountains and Pacific Northwest, it occurs at moderate elevations where moisture is adequate, often growing alongside other willows, alders, and cottonwoods in complex riparian plant communities. The species’ northern distribution extends well into Canada, where it is an important component of boreal forest and prairie pothole ecosystems.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Pussy Willow: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Pussy Willow is among the easiest native woody plants to grow, thriving with minimal care once established in appropriate conditions. Its preference for moist soils and tolerance for wet conditions make it particularly valuable for challenging sites where many other ornamental plants struggle, while its fast growth and early spring interest make it rewarding for impatient gardeners.

Light

Pussy Willow performs best in full sun, where it develops the most compact form and produces the most abundant catkins. The plant can tolerate light partial shade, but flowering may be reduced and growth tends to become more open and leggy in shadier conditions. Full sun exposure also promotes better air circulation, which helps prevent potential fungal issues in humid climates.

Soil & Water

The key to successful Pussy Willow cultivation is providing adequate moisture. The plant thrives in consistently moist to wet soils and is one of the few woody ornamentals that tolerates seasonal flooding and standing water. It grows well in a variety of soil types, from heavy clay to sandy loam, as long as moisture is adequate. While established plants show some drought tolerance, prolonged dry periods can stress the plant and reduce vigor. For best results, plant in areas with natural moisture or provide supplemental irrigation during dry spells.

Planting Tips

Plant Pussy Willow in early spring or fall when temperatures are moderate and natural moisture is typically higher. Choose a location with full sun and consistent moisture, such as near downspouts, in rain gardens, or along water features. Space plants 8-12 feet apart for screening, or give single specimens 12-15 feet of space. The plant establishes quickly and may even grow from unrooted cuttings stuck directly in moist soil — a characteristic shared by many willows.

Pruning & Maintenance

Pussy Willow benefits from annual pruning to maintain shape and encourage abundant catkin production. Prune immediately after the catkins fade and before new growth begins, cutting back about one-third of the previous year’s growth. This encourages vigorous new shoots that will produce the best catkins the following spring. Remove any dead, damaged, or crossing branches during the dormant season. The plant may produce root suckers that can be removed if a single-stemmed form is desired, or left to develop for a more naturalistic colony.

Landscape Uses

Pussy Willow’s unique characteristics make it valuable in numerous landscape applications:

- Rain gardens and bioswales — excellent for managing stormwater runoff

- Riparian restoration — helps stabilize stream banks and provides habitat

- Wildlife gardens — early pollen source and nesting sites for birds

- Specimen planting — dramatic early spring interest as focal point

- Naturalized screens — fast-growing privacy barrier

- Cut flower gardens — branches force easily indoors for early spring bouquets

- Wetland gardens — thrives in bog gardens and pond edges

- Erosion control — extensive root system stabilizes soil on slopes

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Pussy Willow provides exceptional wildlife value throughout the year, serving as both an early-season lifeline for pollinators and a cornerstone habitat species for numerous birds, mammals, and insects. Its position as one of the first plants to bloom each spring makes it critically important for supporting wildlife communities emerging from winter dormancy or beginning spring migrations.

For Birds

At least 35 species of birds utilize Pussy Willow for food, nesting, or cover. The early catkins provide essential pollen and nectar for winter-surviving insects, which in turn support insectivorous songbirds during the lean period before most plants begin growing. The dense, flexible branching structure makes excellent nesting habitat for numerous species including American Goldfinches, Red-winged Blackbirds, Yellow Warblers, and various flycatchers. Game birds such as Ruffed Grouse browse the buds and catkins, while many species use the dense growth for roosting and escape cover. The plant’s tendency to form colonies creates particularly valuable habitat patches in riparian areas.

For Mammals

White-tailed deer and moose browse Pussy Willow twigs and foliage, particularly in winter when other food sources are scarce. Beavers occasionally use the wood for dam construction, while smaller mammals such as rabbits and mice feed on the bark and twigs. The dense root system and colony-forming habit create excellent cover for small mammals, while the moist soil environment supports abundant populations of insects and other invertebrates that serve as food for shrews, voles, and other species.

For Pollinators

Pussy Willow is among the most important early-season pollen sources in northern climates, supporting numerous species of native bees, flies, and other insects when few other flowers are available. Honeybees often rely heavily on willow pollen to build up their colonies for the coming season, while many native bee species depend on early willows to survive the critical gap between winter survival and the emergence of summer flowers. The abundant pollen is particularly valuable for generalist pollinators, though some specialist bees are adapted specifically to willow pollen.

Ecosystem Role

As a dominant component of riparian ecosystems, Pussy Willow plays multiple critical ecological roles. Its extensive, fibrous root system helps prevent stream bank erosion while filtering nutrients and pollutants from surface water runoff. The plant’s ability to colonize disturbed or flood-damaged areas makes it important for ecosystem recovery and succession. In wetland environments, Pussy Willow provides structural diversity that supports complex communities of amphibians, reptiles, and aquatic insects. The annual leaf litter contributes organic matter to aquatic ecosystems, supporting the base of the food web in streams and ponds.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Pussy Willow holds deep cultural significance across many human societies, serving both practical and symbolic purposes for thousands of years. Indigenous peoples throughout the plant’s range recognized and utilized various parts of the plant, with many tribes incorporating the bark into traditional medicines. The inner bark contains salicin, the compound that gives aspirin its pain-relieving properties, and was commonly prepared as teas or poultices for treating headaches, fevers, and inflammatory conditions. Some tribes also used the flexible twigs for basket weaving and the construction of fish traps and other tools.

The plant’s symbolic significance is perhaps even more important than its practical uses. Many Native American cultures viewed the emergence of pussy willow catkins as a crucial seasonal marker, signaling the time for maple syrup collection, early fishing, and other spring activities. The soft, fuzzy catkins were often incorporated into ceremonies celebrating the return of spring and the renewal of life cycles.

European settlers quickly adopted both the practical and cultural significance of Pussy Willow. The plant became a beloved harbinger of spring in rural communities, where branches were commonly brought indoors to force early blooming during the late winter months. This practice continues today and has made Pussy Willow a popular florist crop. In Christian traditions, Pussy Willow branches are often used in Palm Sunday celebrations in northern climates where palm fronds are not available, symbolizing the triumphant entry of Jesus into Jerusalem.

In modern times, Pussy Willow has become an important plant in habitat restoration and sustainable landscaping practices. Its rapid growth, soil stabilization properties, and exceptional wildlife value have made it a cornerstone species in riparian restoration projects throughout its range. The plant is increasingly used in rain gardens and green infrastructure projects, where its tolerance for wet conditions and ability to filter pollutants provide both aesthetic and environmental benefits. Commercial cultivation for the cut flower industry has also developed, particularly in the Pacific Northwest, where Pussy Willow branches are harvested for both domestic and international floral markets.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do some Pussy Willows produce catkins and others don’t?

Pussy Willow is dioecious, meaning individual plants are either male or female. Only male plants produce the showy, fuzzy catkins we associate with “pussy willows.” Female plants produce smaller, less conspicuous greenish catkins. If you want the traditional pussy willow catkins, make sure to select a male plant when purchasing.

Can I force Pussy Willow branches to bloom indoors?

Yes! This is one of Pussy Willow’s most popular uses. Cut branches in late winter (January-February) and place them in water indoors. The warmth will cause the catkins to emerge and expand within 1-2 weeks. Change the water every few days and trim the stem ends periodically for best results.

How fast does Pussy Willow grow?

Pussy Willow is a fast-growing plant, typically adding 2-4 feet per year under good conditions. Young plants can reach significant size quickly, often producing catkins within 2-3 years of planting. This rapid growth makes it excellent for quick screening or habitat establishment.

Is Pussy Willow invasive or aggressive?

While Pussy Willow can spread by root suckers and readily establishes from cuttings, it is native throughout its range and not considered invasive. However, it can be somewhat aggressive in ideal conditions, forming colonies over time. This trait is often desirable for erosion control and habitat creation but should be considered in smaller garden settings.

Can Pussy Willow tolerate salt and urban conditions?

Pussy Willow has moderate tolerance for road salt and urban conditions, though it is less tolerant than some other native plants. It performs better in suburban and rural settings with cleaner air and water. In urban areas, it’s best planted away from heavily salted roads and in locations with adequate moisture and drainage.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Pussy Willow?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota