Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis)

Rubus spectabilis, commonly known as Salmonberry, is a spectacular deciduous shrub that epitomizes the vibrant understory of Pacific Northwest forests. This remarkable member of the rose family produces some of the region’s most distinctive flowers – brilliant pink to purple blossoms that appear before most other wildflowers have awakened from winter dormancy. Named for its salmon-colored berries that ripen alongside salmon runs, this hardy bramble has sustained Indigenous communities for millennia while providing crucial habitat for countless wildlife species throughout its extensive coastal range.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Rubus spectabilis Pursh |

| Plant Type | Deciduous shrub, bramble |

| Height | 3-13 feet (1-4 meters), occasionally spreading to 30 feet |

| Sun Exposure | Part shade to full sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate to high, prefers consistent moisture |

| Soil Type | Rich, moist, nitrogen-rich soils; streambanks and forest edges |

| Soil pH | 5.5-7.0 (slightly acidic to neutral) |

| Bloom Time | April-July (peaks in May) |

| Flower Color | Bright pink to pinkish-purple |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4-9 |

Identification

Salmonberry is a vigorous deciduous shrub that grows through extensive underground rhizome systems, creating substantial colonies that can persist for decades. The plant exhibits remarkable diversity in form, from low-growing groundcovers in exposed areas to tall, arching canes reaching 13 feet in protected forest settings.

Stems and Growth Habit

The characteristic golden to yellowish-brown canes (stems) are one of salmonberry’s most distinctive features. Unlike many brambles, salmonberry canes are perennial rather than biennial, living for multiple years and bearing both flowers and fruit repeatedly. The stems are armed with fine prickles, particularly on new growth, though they are generally less formidable than those of blackberries. These erect to arching canes often form dense thickets, with individual plants spreading 9 feet or more through rhizomatous growth.

Leaves

The leaves are alternate and trifoliate (three-leafleted), measuring 3-8½ inches long. The terminal leaflet is noticeably larger than the two lateral leaflets, which may be shallowly lobed. Each leaflet has a distinctive ovate shape with doubly serrated margins – small teeth on larger teeth, creating a fine-textured edge. The upper leaf surface is smooth to slightly hairy and bright green, while the underside is paler and more pubescent. The leaves emerge early in spring and provide excellent fall color, turning brilliant yellows and oranges before dropping in late autumn.

Flowers

Salmonberry flowers are among the most spectacular of all Pacific Northwest native plants. The blooms appear from April through July, with peak flowering typically occurring in May, coinciding with hummingbird migration. Each flower is 1-1¼ inches in diameter with five bright pink to pinkish-purple petals surrounding a dense cluster of 75-100 stamens. The flowers are perfect (containing both male and female parts) and are borne singly or in small clusters of 2-3 at the ends of branches. The five hairy sepals provide an attractive green backdrop to the vibrant petals.

Fruit

The aggregate fruits develop 30-36 days after pollination, ripening from early May through late July in most areas, extending into August in northern climates. The berries are ½ to ¾ inch long and exhibit remarkable color polymorphism, ranging from bright yellow-orange to deep red. Like raspberries, the fruit pulls away from the receptacle when picked, distinguishing them from blackberries. Each berry contains 17-65 seeds and has a distinctive flavor profile that varies from bright and fruity to deep and earthy with spicy notes, depending on color morph and growing conditions.

Native Range

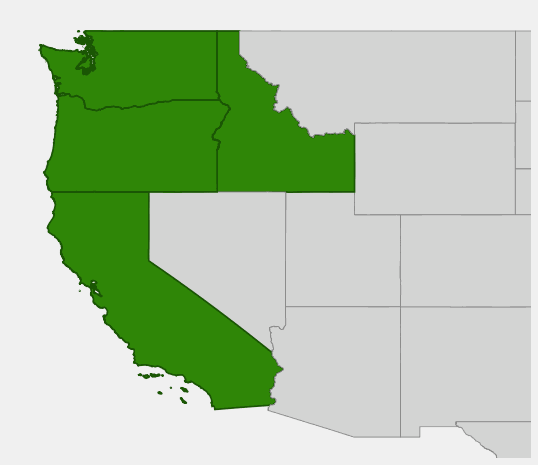

Salmonberry is endemic to the coastal regions of western North America, where it forms a crucial component of temperate rainforest ecosystems. This adaptable species ranges from west-central Alaska south through British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California, with its distribution extending inland as far as Idaho.

The species shows strong affinities for coastal environments with high rainfall and moderate temperatures. It thrives in the fog belt from sea level to approximately 3,000 feet elevation, though it can occasionally be found at higher elevations in protected valleys. Salmonberry reaches its greatest abundance in areas receiving 40+ inches of annual rainfall, declining in drier inland locations.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Salmonberry: Western Oregon & Western Washington

Growing & Care Guide

Salmonberry is an excellent choice for naturalized landscapes, wildlife gardens, and restoration projects. While it requires more consistent moisture than some other native shrubs, it rewards gardeners with spectacular early flowers, nutritious berries, and exceptional wildlife value.

Light Requirements

Salmonberry adapts to a wide range of light conditions, from partial shade to full sun. In its native habitat, it often grows in forest openings, along stream edges, and in clearings where it receives dappled to full sunlight. While it tolerates shade, flowering and fruiting are most prolific in locations receiving at least 4-6 hours of direct sun daily. In hot inland areas, afternoon shade may be beneficial.

Soil Preferences

This species strongly prefers rich, nitrogen-rich soils with consistent moisture. Salmonberry thrives along streambanks, in forest clearings with deep organic soils, and in areas where nitrogen-fixing plants like red alder have enriched the soil. The ideal pH range is 5.5-7.0, though the plant tolerates slightly more alkaline conditions than many Pacific Northwest natives. Good drainage is important, as salmonberry does not tolerate waterlogged conditions despite its preference for moist soils.

Water Requirements

Consistent moisture is crucial for salmonberry success. In coastal areas, natural rainfall typically provides adequate water, but inland plantings require regular irrigation, especially during the dry summer months. Deep, weekly watering during the growing season helps maintain the lush growth that produces the best flowering and fruiting displays. Mulching around plants helps retain soil moisture and suppress competing vegetation.

Planting and Establishment

Plant salmonberry in spring after soil has warmed and the risk of hard frost has passed. Space plants 6-8 feet apart, keeping in mind their eventual spread through rhizomes. In restoration settings, salmonberry can be planted more densely to quickly establish thickets. The plant establishes readily from nursery stock and can also be propagated through division of existing clumps or root cuttings.

Maintenance and Pruning

Once established, salmonberry requires minimal maintenance. Pruning can be done in late winter to shape plants or remove dead, damaged, or overcrowded canes. Unlike many brambles, salmonberry canes live for several years, so avoid cutting healthy wood unless thinning is needed. The plant responds well to hard pruning if renewal is desired, quickly regenerating from its extensive root system.

Propagation

Salmonberry propagates readily through several methods. Division of established clumps in early spring is the most reliable approach for home gardeners. Root cuttings taken in late fall can be planted directly or started in pots. The plant also spreads naturally through rhizomes, making it possible to transplant volunteer shoots. Seed propagation is possible but requires stratification and patience, as germination can be erratic.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Few plants provide greater wildlife value than salmonberry. This keystone species supports complex ecological relationships throughout Pacific Northwest ecosystems, serving as a critical food source, pollinator plant, and habitat provider for numerous animal species.

Pollinator Relationships

The early flowering period of salmonberry makes it invaluable for pollinators emerging from winter dormancy. The timing of peak bloom perfectly coincides with hummingbird migration, providing essential nectar when few other flowers are available. Anna’s hummingbirds, rufous hummingbirds, and Allen’s hummingbirds are frequent visitors, with the plant’s pink flowers specifically evolved to attract these important pollinators.

Native bees, including early-emerging mason bees, mining bees, and bumblebee queens, depend on salmonberry flowers for both nectar and pollen. The abundant stamens provide high-quality protein-rich pollen essential for colony establishment. Beneficial flies, beetles, and other insects also contribute to pollination while foraging on the generous floral resources.

Berry Consumers

The polymorphic berries support an incredible diversity of wildlife. Research has shown that while both red and yellow morphs have similar nutritional value, birds show slight preferences for the red varieties, though this doesn’t appear to strongly influence plant distribution. Major avian consumers include band-tailed pigeons, various thrush species (including the “salmonberry bird” – Swainson’s thrush), grouse, wrentits, and numerous songbirds.

Mammals ranging from black bears and deer to small rodents harvest the nutritious berries. Bears are particularly important dispersers, as they can deposit 50,000 to 100,000 seeds in a single scat pile, helping establish new populations across the landscape. Red squirrels, Douglas squirrels, and chipmunks cache berries for winter food stores.

Herbivore Support

The tender young shoots provide crucial early-season browse for deer, elk, moose, mountain goats, and rabbits. Indigenous peoples recognized this relationship and timed their own shoot harvest to coincide with peak palatability. The shoots are particularly valuable because they emerge before most other browse plants have leafed out, providing critical nutrition during the “hunger gap” of late winter and early spring.

Habitat Value

Dense salmonberry thickets provide essential nesting sites and protective cover for numerous bird species, small mammals, and amphibians. The multi-stemmed growth habit creates complex microhabitats that support different species at various heights. Ground-nesting birds benefit from the overhead protection, while cavity-nesting species use the dense branching for nest sites.

Ecosystem Services

Salmonberry plays important roles in soil stabilization and nutrient cycling. The extensive root system helps prevent erosion along streambanks and slopes, while the annual leaf drop contributes organic matter to forest soils. The plant’s fire-adapted traits, including buried rhizomes and rapid post-fire regeneration, help maintain ecosystem continuity after disturbance events.

Cultural and Historical Significance

For thousands of years, salmonberry has been central to the cultures and survival of Pacific Northwest Indigenous peoples. The plant’s importance extends far beyond nutrition, encompassing seasonal indicators, trade relationships, and traditional ecological knowledge systems.

Traditional Food Use

Both the berries and young shoots were extensively utilized by Indigenous communities. The shoots, harvested from April through early June before they became woody, were peeled and eaten fresh, steamed, boiled, or pit-cooked. They provided essential vitamins and minerals during the late winter and early spring when few other fresh foods were available. The shoots were sometimes mixed with salmon or oolichan grease for enhanced nutrition and flavor.

Berries were eaten fresh during the harvesting season and were integral to ceremonial feasts. Unlike many other berries, salmonberries were rarely dried due to their high moisture content, making them particularly valuable as fresh food during summer months. Different Indigenous groups developed sophisticated knowledge about which color morphs and microhabitats produced the best-flavored fruits.

Traditional Names and Phenology

Indigenous peoples developed rich vocabulary around salmonberry, with distinct names for the plant, berries, and shoots across dozens of languages. The Makah people call the plant ka’k’we’abupt and the berry ka’k’we; the Squamish people call the plant yetwánáy and the berries yetwán, while the shoots are called stsá7tskaý (pronounced saskay).

Perhaps most remarkably, many Pacific Northwest Indigenous cultures recognized the connection between the song of Swainson’s thrush and salmonberry ripening. This “salmonberry bird” was believed to actually cause the berries to ripen through its song, with the Saanich people translating the birdsong as “xwexwelexwelexwelexwesh!” meaning “ripen, ripen, ripen, ripen!” This sophisticated phenological knowledge demonstrates the deep ecological understanding that guided traditional resource management.

Medicinal and Other Uses

Beyond nutrition, salmonberry had important medicinal applications. Various groups used the leaves for flavoring fish during cooking, the bark for treating burns and wounds, and bark preparations for reducing labor pains and treating infections. The plant’s astringent properties made it valuable for treating various ailments, and winter preparations using the bark extended its medicinal availability year-round.

Modern Applications

Today, salmonberry is experiencing renewed interest among chefs and food enthusiasts for its unique flavor profiles and nutritional benefits. The berries are rich in vitamin C, antioxidants, and other beneficial compounds. Foraging guides and native food advocates promote sustainable harvesting practices that honor traditional knowledge while making this remarkable food source available to broader communities.

Landscape Applications

Salmonberry offers tremendous versatility in contemporary landscapes, particularly for gardeners seeking to create naturalized, wildlife-friendly environments that capture the essence of Pacific Northwest forests.

Wildlife Gardens

As one of the most valuable wildlife plants in the Pacific Northwest, salmonberry is indispensable in gardens designed to support local ecosystems. The early bloom period provides crucial nectar sources when few other plants are flowering, while the berries extend food availability through summer months. The plant’s structure provides nesting sites and cover for numerous species.

Restoration and Naturalization

Salmonberry excels in restoration applications, quickly establishing colonies that help stabilize disturbed sites. Its ability to thrive in early successional environments makes it valuable for rehabilitating clearings, streambanks, and other degraded areas. The plant’s nitrogen-fixing associates like red alder often establish alongside salmonberry, creating beneficial plant communities.

Edible Landscapes

For food-focused gardeners, salmonberry provides both early-season shoots and summer berries. The colorful berries are excellent fresh, in jams, or incorporated into desserts and beverages. The ornamental value of the brilliant pink flowers makes salmonberry an attractive choice for edible landscaping where beauty and function combine.

Screening and Privacy

The vigorous growth and dense thicket formation make salmonberry effective for natural screening and privacy plantings. Unlike formal hedge plants, salmonberry provides dynamic seasonal interest with spring flowers, summer berries, and fall color, while supporting wildlife throughout the growing season.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is salmonberry invasive or aggressive?

Within its native range, salmonberry is not invasive but rather an appropriate and beneficial component of natural ecosystems. The plant does spread through rhizomes and can form substantial colonies, so it may be too vigorous for small formal gardens. However, it can be managed through selective pruning and root barriers if needed.

When are salmonberry shoots best for harvesting?

Young shoots are best harvested from April through early June, before they become woody and tough. Look for tender, green shoots that snap easily when bent. Always harvest sustainably, taking only what you need and leaving plenty for plant health and wildlife.

What’s the difference between red and yellow salmonberry fruits?

Both color morphs are equally edible and nutritious, with slight variations in flavor. Red berries tend to have deeper, earthier flavors while yellow-orange berries often taste brighter and more citrusy. The color polymorphism appears to be genetically controlled and may be maintained by different selective pressures.

Can I grow salmonberry in drier climates?

Salmonberry requires consistent moisture and may struggle in areas with long, dry summers without supplemental irrigation. It’s best suited for areas receiving at least 30 inches of annual rainfall or where regular watering can be provided. In marginal climates, choose the most humid, protected locations.

Do I need both red and yellow varieties for fruiting?

Salmonberry flowers cannot self-pollinate and require cross-pollination between different plants. However, color morph doesn’t affect pollination compatibility – any two different salmonberry plants can pollinate each other regardless of their fruit color. Having multiple plants will significantly increase berry production.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Salmonberry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: Oregon · Washington