Summer Phlox (Phlox paniculata)

Phlox paniculata, commonly known as Summer Phlox, Garden Phlox, or Wild Sweet William, represents the perfect marriage of native plant authenticity and garden-worthy beauty, bringing intense color and intoxicating fragrance to summer landscapes across eastern and central North America. This robust perennial member of the Polemoniaceae (phlox) family forms impressive clumps of upright stems that can reach 2-4 feet in height, each topped with large, dome-shaped panicles of flowers in shades ranging from pure white through soft pink to deep magenta and purple. The flowers are intensely fragrant, particularly in the evening hours, filling summer gardens with a sweet perfume that draws both human admirers and pollinating insects from considerable distances.

In its native habitat, Summer Phlox occupies the rich, moist soils of woodland edges, stream banks, and meadow borders where it receives morning sun but enjoys some relief from the harsh afternoon heat of midsummer. These transitional habitats — the ecotones between full forest and open grassland — provide the perfect combination of light, moisture, and soil fertility that allows Summer Phlox to reach its full potential. The plant forms slowly expanding clumps through shallow rhizomes, creating naturalistic drifts over time while never becoming aggressively invasive. This restrained spreading habit, combined with its spectacular floral display, makes it ideal for both wild gardens and more formal perennial borders.

The botanical structure of Summer Phlox reveals fascinating adaptations for attracting and rewarding pollinators. Each individual flower features five rounded petals that form a flat face about ¾ inch across, with a narrow tube extending behind that contains the nectar reward. This flower structure is perfectly designed to accommodate the proboscises of butterflies and the beaks of hummingbirds, both of which are primary pollinators of the species. The large, dense flower clusters can contain dozens of individual blooms, creating landing platforms for butterflies while providing abundant nectar resources during the peak of summer when many other native plants have finished blooming. The extended blooming period — often 6-8 weeks from midsummer through early fall — makes Summer Phlox particularly valuable for supporting pollinators during the challenging late-season period.

While Summer Phlox has been widely cultivated and bred into numerous garden varieties over the past century, the straight native species offers distinct advantages over many hybrid cultivars. Wild-collected plants typically show superior disease resistance, particularly to powdery mildew, which can plague garden varieties in humid climates. They also tend to be more drought-tolerant once established and provide better wildlife value due to their authentic genetic makeup. The native form usually produces viable seeds, allowing for natural reproduction and genetic diversity, while many cultivars are sterile hybrids. For gardeners seeking to combine horticultural beauty with ecological authenticity, the straight species represents an ideal choice that honors both aesthetic desires and conservation goals.

Identification

Summer Phlox presents a classic perennial form, developing sturdy, upright clumps that serve as reliable backbone plants in mixed borders and naturalistic plantings. The species typically reaches 2-4 feet in height, with robust, unbranched stems arising from a slowly spreading rhizomatous root system. Unlike many native perennials that can be aggressive spreaders, Summer Phlox expands its territory gradually and politely, making it suitable for both wild gardens and more formal settings where restraint is valued.

Stems & Architecture

The stems of Summer Phlox are notably sturdy and self-supporting, rarely requiring staking even in windy locations. They emerge in early spring as reddish shoots that quickly develop into strong, cylindrical stems with a slightly square cross-section. The stem surfaces are generally smooth, though they may develop a slightly rough texture with age. Stem color ranges from green to purplish-green, often with reddish nodes where the leaves attach.

The branching pattern is relatively simple — stems typically remain unbranched until they reach their full height, at which point they may develop a few short lateral branches just below the main flower cluster. This architectural simplicity creates clean, vertical lines in the garden and allows the dramatic flower heads to serve as the primary focal points. The leaf arrangement follows a strict opposite pattern, with each pair of leaves positioned at right angles to the pair above and below.

Foliage Characteristics

The leaves of Summer Phlox are simple, lance-shaped to narrowly oval, and arranged in opposite pairs along the stems. Typical leaf dimensions range from 3-6 inches in length and 1-2 inches in width, though lower leaves are generally larger than those near the top of the stem. The leaf margins are smooth (entire) without teeth or serrations, and the surfaces may be either smooth or slightly rough depending on the specific population.

Leaf color is typically medium to dark green, though it may show subtle variations depending on growing conditions and seasonal changes. The prominent parallel venation creates attractive ribbed patterns on the leaf surfaces, and the leaves have a substantial, somewhat leathery texture that helps them withstand summer heat and drought. In autumn, the foliage may develop yellowish tones before the plant dies back to its underground rhizomes for winter dormancy.

One characteristic that gardeners should be aware of is Summer Phlox’s susceptibility to powdery mildew, particularly in humid climates or areas with poor air circulation. This fungal disease appears as a white, powdery coating on leaf surfaces and can significantly detract from the plant’s appearance if severe. However, native populations are generally more resistant than many garden cultivars, and proper siting with good air movement can minimize disease problems.

Spectacular Flower Clusters

The flowers of Summer Phlox are arranged in large, dome-shaped or pyramidal terminal panicles that can measure 4-6 inches across and contain dozens of individual blooms. These impressive flower heads serve as landing platforms for butterflies while creating substantial visual impact in the garden. The flowering period typically extends from midsummer through early fall, with individual flowers opening in succession to maintain the display over many weeks.

Each individual flower measures about ¾ inch across and consists of five rounded petals that form a flat, circular face. The petals are joined at their bases into a narrow tube about ½ inch long that contains the nectar reward. This tubular structure is perfectly proportioned for butterfly proboscises and hummingbird beaks, making Summer Phlox particularly attractive to these important pollinators. The flower colors in wild populations typically range from white through various shades of pink to deep magenta or purple, often with contrasting centers or subtle color variations within individual blooms.

The fragrance of Summer Phlox flowers is one of their most memorable characteristics — a sweet, honey-like perfume that intensifies in the evening hours and can perfume entire garden areas. This evening fragrance serves to attract night-flying moths, which are important pollinators for the species. The combination of daytime butterfly activity and nighttime moth visitation ensures effective pollination and seed set in natural populations.

Seed Production & Dispersal

Following successful pollination, Summer Phlox produces small, three-chambered capsules that contain 1-3 seeds each. The seeds are relatively large for a phlox — typically about 1/8 inch long — and are brown to black in color with a somewhat angular shape. When the capsules mature in late fall, they split open to release the seeds, which may be dispersed by wind, water, or small animals.

The seeds of Summer Phlox generally require a period of cold stratification over winter before they will germinate the following spring. In garden settings, allowing some flower heads to go to seed can result in attractive self-sown seedlings that may display slight variations in flower color and other characteristics, adding to the naturalistic appeal of native plant gardens.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Phlox paniculata |

| Family | Polemoniaceae (Phlox) |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous Perennial |

| Mature Height | 2–4 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | July – September |

| Flower Color | Pink, purple, white |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–8 |

Native Range

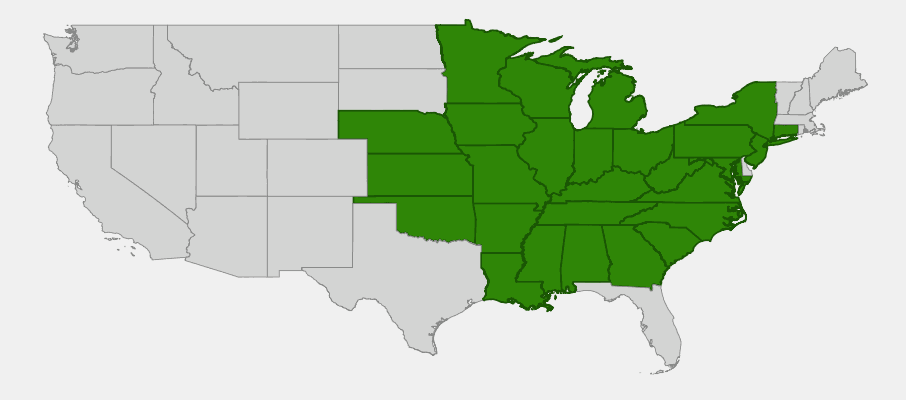

Summer Phlox is native to eastern and central North America, with a natural range that extends from southern Ontario and Quebec south to northern Georgia and from the Atlantic coastal plain west to the Great Plains of Kansas and Nebraska. This extensive distribution covers most of the eastern deciduous forest region and includes significant portions of the tallgrass prairie ecosystem, where Summer Phlox typically grows along woodland edges and in moist meadow openings. The species reaches its greatest abundance in the Ohio River Valley and the prairie-forest transition zone of Illinois, Indiana, and Missouri, where it forms spectacular naturalized colonies in suitable habitat.

Throughout its native range, Summer Phlox consistently seeks out rich, moist soils with good organic content, typically in areas that receive morning sun but some protection from the intense heat of midsummer afternoons. These requirements usually translate to woodland edges, stream banks, moist meadows, and the margins of wetlands where soil moisture remains relatively constant throughout the growing season. The species is rarely found in deeply shaded forest interiors or in exposed, drought-prone locations, preferring instead the intermediate conditions found in transitional habitats.

The historical distribution of Summer Phlox was closely tied to the natural fire regimes that maintained the open woodlands and prairie-forest borders where the species thrives. Periodic fires prevented complete forest closure, created favorable germination sites, and maintained the light levels necessary for optimal flowering. The suppression of natural fire cycles over the past century has led to forest succession in many areas where Summer Phlox was once common, contributing to population declines throughout portions of its range. However, the species remains relatively abundant compared to many other native wildflowers, partly due to its adaptability and its ability to persist in partially disturbed habitats.

Modern conservation challenges for Summer Phlox include habitat fragmentation, invasive species competition, and hybridization with escaped garden cultivars. The widespread cultivation of Summer Phlox and its numerous hybrid varieties has led to concerns about genetic pollution of wild populations, as garden plants can cross-pollinate with native individuals and potentially dilute the genetic integrity of local populations. Conservation efforts now emphasize the importance of using only locally sourced, genetically appropriate plant material for restoration projects and encouraging gardeners to choose straight native species over hybrid cultivars when possible.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Summer Phlox: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Successfully cultivating native plants requires understanding their natural habitat preferences and recreating those conditions in garden settings. The key to thriving native plant gardens lies in matching plants to appropriate sites rather than trying to force plants to adapt to unsuitable conditions.

Light Requirements

Summer Phlox performs best in partial sun to light shade conditions — typically 4-6 hours of morning sunlight with some protection from harsh afternoon sun. In its natural habitat, it grows along woodland edges and in meadow openings where it receives bright light but not the full intensity of midday summer sun. This preference for partial sun is particularly important in southern climates, where intense afternoon heat can stress the plants and increase susceptibility to powdery mildew.

In cooler northern climates, Summer Phlox can tolerate more sun, even thriving in full sun locations with adequate moisture. However, in all climates, some air movement is beneficial to reduce humidity around the foliage and minimize disease problems. Avoid planting in deep shade, where plants will become tall, weak, and prone to flopping, with reduced flowering.

Soil & Water Requirements

Summer Phlox prefers rich, fertile soil with consistent moisture throughout the growing season. The ideal soil is deep, well-drained loam with high organic content — similar to the rich bottomland soils where it grows naturally along streams and in moist meadows. Heavy clay soils should be amended with compost to improve drainage and soil structure, while sandy soils benefit from organic matter additions to improve water and nutrient retention.

Consistent moisture is particularly important during the blooming period, as drought stress can shorten the flowering season and reduce flower quality. However, soil drainage is equally critical — waterlogged conditions promote root rot and increase susceptibility to foliar diseases. A 2-3 inch mulch of organic matter helps maintain consistent soil moisture while suppressing weeds and moderating soil temperature.

Soil pH should be slightly acidic to neutral (6.0-7.0) for optimal growth. Summer Phlox is somewhat tolerant of higher pH levels but may show reduced vigor and flower quality in strongly alkaline soils. Regular additions of organic matter help buffer soil pH while providing the nutrients necessary for vigorous growth and abundant flowering.

Planting & Establishment

The best time for planting most native perennials is early fall, which allows plants to establish strong root systems before the stress of their first summer. Spring planting is also successful but requires more careful attention to watering during the first growing season. When planting, dig holes only as deep as the root ball but 2-3 times as wide to encourage lateral root development.

Space plants according to their mature spread requirements, allowing adequate room for air circulation to prevent disease problems. Water thoroughly after planting and maintain consistent moisture for the first full growing season while plants establish. Mulching is particularly important for newly planted natives, as it moderates soil temperature, conserves moisture, and suppresses weed competition.

Pruning & Maintenance

Native plants generally require less maintenance than non-native alternatives, but some basic care helps ensure optimal performance. Deadheading spent flowers can extend the blooming period and prevent excessive self-seeding, though many gardeners prefer to leave some seed heads for wildlife food and winter interest.

Most herbaceous natives can be cut back in late fall or early spring, though leaving the stems through winter provides seed for birds and overwintering habitat for beneficial insects. Remove any diseased or damaged foliage promptly to prevent disease spread, and divide overcrowded clumps every 3-4 years to maintain vigor.

Landscape Applications

Native plants excel in naturalistic landscape designs that work with natural processes rather than against them. Consider these applications:

- Native plant gardens that recreate regional plant communities

- Rain gardens for managing stormwater runoff

- Pollinator gardens that support local wildlife

- Restoration projects for damaged or degraded sites

- Low-maintenance landscapes that reduce input requirements

- Educational gardens that showcase regional natural heritage

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Native plants form the foundation of healthy ecosystems, providing food, shelter, and habitat complexity that supports biodiversity at multiple levels. Each native plant species has evolved complex relationships with local wildlife over thousands of years, creating irreplaceable ecological connections that cannot be replicated by non-native alternatives.

For Birds

While Summer Phlox may not produce seeds that are primary food sources for birds, its ecological value for avian species is substantial through its support of insect communities. The abundant, long-lasting flowers attract numerous species of moths, butterflies, bees, and other insects, which in turn become important food resources for insectivorous birds. During the critical breeding season, when many songbird species require protein-rich insects to feed their rapidly growing nestlings, the insect communities supported by Summer Phlox become essential components of the food web.

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are among the most conspicuous visitors to Summer Phlox flowers, as the tubular flower structure and abundant nectar make them ideal hummingbird plants. The extended blooming period of Summer Phlox — often 6-8 weeks from midsummer through early fall — provides crucial nectar resources during the late summer period when many other native flowers have finished blooming. This timing is particularly important for hummingbirds, as they need to build energy reserves for their remarkable migration journeys to Central America.

The tall, sturdy stems of Summer Phlox also provide valuable perching sites for various songbirds, while the winter seed heads offer food for finches and other seed-eating species. In naturalistic gardens where Summer Phlox is allowed to self-seed and form colonies, the diverse age structure and density variations create microhabitat complexity that supports higher bird diversity than more formal plantings.

For Pollinators

Summer Phlox represents a pollinator powerhouse among native plants, attracting an extraordinary diversity of butterflies, moths, bees, and other beneficial insects throughout its extended blooming period. The large, flat-topped flower clusters serve as convenient landing platforms for butterflies, while the tubular individual flowers provide abundant nectar rewards. The flower structure is particularly well-suited to long-tongued pollinators, including various species of butterflies, sphinx moths, and long-tongued bees that can reach the nectar at the base of the flower tubes.

Among butterflies, Summer Phlox is especially valuable for supporting species with longer proboscises, including swallowtails, fritillaries, and skippers. The intense fragrance of the flowers, which becomes most pronounced in the evening hours, serves to attract night-flying moths, including the spectacular hummingbird clearwing moth (Hemaris thysbe) and various sphinx moth species. These night-flying pollinators are often overlooked but play crucial roles in ecosystem function and represent some of the most beautiful and interesting insects in North America.

The extended blooming period of Summer Phlox — often lasting 6-8 weeks from midsummer through early fall — makes it particularly valuable for supporting pollinator communities during the late summer period when many other native flowers have finished blooming. This timing is critical for butterflies that are building energy reserves for migration or overwintering, and for late-emerging bee species that need access to high-quality nectar sources. The reliable, abundant nectar production of Summer Phlox makes it a cornerstone species in pollinator conservation gardens and restoration projects.

For Mammals

Native plants support mammalian wildlife through direct food resources, habitat structure, and the complex food webs they create. Even plants that don’t provide obvious mammal foods often support the insects, seeds, and other resources that mammals depend on indirectly.

Summer Phlox supports mammalian wildlife primarily through its extensive relationships with insect communities, which become food sources for insectivorous mammals including various species of bats. The evening fragrance that attracts night-flying moths also creates feeding opportunities for bat species that hunt over flowering meadows and garden areas. The diverse insect communities supported by Summer Phlox — including caterpillars, beetles, and other insects that feed on the foliage — provide food resources for small mammals including shrews and various mouse species.

The seeds of Summer Phlox are consumed by various small granivorous mammals, though this represents a relatively minor component of their diets. More significantly, the plant’s tendency to form colonies over time creates habitat structure that supports small mammal communities. The dense herbaceous growth provides cover for ground-dwelling mammals, while the diverse insect life associated with the plants creates foraging opportunities throughout the growing season.

In naturalistic landscapes where Summer Phlox is allowed to form extensive colonies, the habitat complexity created by plants of varying ages and densities supports higher mammalian diversity than more formal garden plantings. This structural diversity is particularly important for small mammals that require various microhabitats for nesting, foraging, and escape cover.

Ecosystem Relationships

The true ecological value of native plants lies not in any single function but in their complex web of relationships with other organisms. Each native plant species has evolved over millennia to fit precisely into local ecosystems, creating relationships that cannot be replicated by non-native alternatives regardless of their ornamental value or practical benefits.

Native plants support far more insect diversity than non-native plants — research by Dr. Douglas Tallamy and others has shown that native plants support 35 times more butterfly and moth species than non-native plants. This insect diversity forms the foundation of food webs that support birds, mammals, amphibians, and other wildlife. The loss of native plants therefore creates cascading effects throughout entire ecosystems, reducing wildlife diversity at multiple trophic levels.

Beyond their direct relationships with animals, native plants play crucial roles in maintaining healthy soil ecosystems. Their root systems, leaf litter, and chemical compounds create soil conditions that support diverse communities of bacteria, fungi, and invertebrates. These soil organisms, in turn, cycle nutrients, improve soil structure, and create the foundation for healthy plant communities. The replacement of native plants with non-native alternatives often disrupts these belowground ecosystems, leading to simplified, less resilient soil communities.

Cultural & Historical Uses

The relationship between North America’s indigenous peoples and their native plants represents thousands of years of accumulated knowledge about sustainable resource use, ecological management, and the medicinal properties of native species. This traditional ecological knowledge provides invaluable insights into plant uses and conservation strategies that remain relevant today.

Summer Phlox has been valued by indigenous peoples across its native range for both its practical applications and its role in traditional ecological knowledge systems. While perhaps not as extensively utilized as some other native plants, Summer Phlox nevertheless played meaningful roles in the traditional cultures of many Native American tribes, particularly those in the eastern woodlands and prairie-forest transition zones where the species is most abundant.

The Cherokee people, whose traditional territory encompassed much of the southeastern portion of Summer Phlox’s range, used various parts of the plant in their sophisticated medical system. The roots were typically harvested in fall and prepared as infusions for treating stomach ailments and digestive problems. Cherokee healers also used Summer Phlox preparations externally for treating skin conditions and wounds, taking advantage of compounds in the plant that have mild antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties.

Several tribes in the Great Lakes region, including the Menominee and Potawatomi, incorporated Summer Phlox into their traditional pharmacopeias as a treatment for respiratory ailments. The fragrant flowers were sometimes used in steam treatments for coughs and congestion, while root preparations were used for more serious respiratory conditions. The timing and method of preparation were considered crucial to the effectiveness of these treatments, with specific protocols developed through generations of careful observation and experimentation.

Beyond its medicinal applications, Summer Phlox played roles in the ceremonial and spiritual life of various Native American communities. The intensely fragrant flowers made them valuable for ceremonial purposes, and some tribes incorporated phlox into rituals related to seasonal transitions and agricultural activities. The plant’s tendency to bloom during the height of summer made it a natural marker for certain seasonal activities and ceremonial observances.

Early European botanists and plant collectors were immediately attracted to Summer Phlox’s garden potential, and it became one of the first North American wildflowers to be extensively cultivated and hybridized in European gardens. By the 18th century, Summer Phlox had become a popular garden plant in England and other European countries, where plant breeders began developing the numerous cultivars and color forms that characterize modern garden phlox.

The extensive cultivation and breeding of Summer Phlox in Europe and later in North America led to the development of hundreds of named cultivars, many of which bear little resemblance to their wild ancestors. While this horticultural development brought Summer Phlox to prominence in ornamental gardening, it also created challenges for conservation, as escaped garden varieties can potentially hybridize with wild populations and dilute their genetic integrity.

In contemporary times, Summer Phlox has found new relevance in the growing movement toward native plant gardening and ecological landscape design. Modern gardeners and landscapers increasingly recognize the advantages of using straight native species rather than highly bred cultivars, both for their superior wildlife value and their better adaptation to local growing conditions. This renewed interest in native forms of Summer Phlox has led to increased availability of wild-type plants and greater awareness of the species’ conservation needs.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I successfully establish this plant in my garden?

Success with native plants begins with site selection — choose a location that matches the plant’s natural habitat preferences for light, soil, and moisture conditions. Plant in early fall when possible to allow root establishment before winter, and maintain consistent moisture during the first growing season. Mulching with organic matter helps retain moisture and suppress weeds while the plant establishes.

When is the best time to plant native species?

Early fall is generally the optimal planting time for most native perennials, as cooler temperatures and increased rainfall reduce transplant stress while allowing plants to develop strong root systems before their first summer. Spring planting is also successful but requires more careful attention to watering during establishment. Avoid planting during the heat of summer unless you can provide intensive care and irrigation.

How long does it take for native plants to become established?

Most native perennials require 2-3 full growing seasons to become fully established, though many will flower in their first or second year. The old saying “first year they sleep, second year they creep, third year they leap” applies well to native plant establishment. Patience during the establishment period is crucial, as native plants are investing energy in developing deep, extensive root systems that will support long-term health and drought tolerance.

Do native plants really require less maintenance than non-native plants?

Once established, native plants typically require significantly less maintenance than non-native alternatives because they are adapted to local climate, soil, and pest conditions. However, they do require some maintenance, particularly during establishment and in garden settings where they may be grown outside their optimal habitat conditions. The key is choosing plants appropriate for your specific site conditions rather than trying to force plants to adapt to unsuitable locations.

Can I grow native plants in formal garden settings?

Absolutely! Many native plants are perfectly suitable for formal gardens and can be incorporated into traditional landscape designs. The key is selecting species that match your design goals and site conditions, then providing appropriate care during establishment. Many native plants actually perform better than non-native alternatives in formal settings because they are better adapted to local growing conditions.

How do I know if a plant is truly native to my area?

True natives are species that evolved in your region prior to European settlement and are genetically adapted to local conditions. Check regional flora guides, native plant society resources, and botanical databases to verify native status. Be aware that plant sellers sometimes use the term “native” loosely, including plants that are native to North America but not necessarily to your specific region. When possible, choose plants that are not just regionally native but are sourced from local genetic stock.

What’s the difference between native plants and cultivars of native plants?

Native plants are the straight species as they exist in wild populations, while cultivars (cultivated varieties) are selected or bred forms that may differ in color, size, bloom time, or other characteristics. While cultivars can be attractive and may have some wildlife value, they often provide less ecological benefit than straight native species and may not be adapted to local conditions. For maximum wildlife and ecological value, choose straight native species when possible.

How do native plants help local wildlife?

Native plants form the foundation of local food webs, supporting far more insect diversity than non-native plants. These insects, in turn, provide food for birds, bats, and other wildlife. Native plants also provide appropriate nesting materials, shelter, and seasonal resources that wildlife have evolved to depend on. The complex relationships between native plants and wildlife cannot be replicated by non-native alternatives, regardless of their beauty or practical benefits.

Looking for a nursery that carries Summer Phlox?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina