Western Honeysuckle (Lonicera ciliosa)

Lonicera ciliosa, commonly known as Western Honeysuckle or Orange Honeysuckle, is a magnificent deciduous climbing vine native to the forests and woodlands of western North America. With its brilliant orange-yellow trumpet-shaped flowers and attractive blue-green foliage, this native honeysuckle brings both beauty and ecological value to Pacific Northwest gardens. Belonging to the Caprifoliaceae (honeysuckle) family, it differs dramatically from invasive honeysuckle species by its restrained growth habit, native wildlife support, and stunning floral display that attracts hummingbirds from miles around.

Unlike aggressive non-native honeysuckles that can smother native vegetation, Western Honeysuckle grows with a graceful, manageable form that integrates beautifully with native plant communities. Its distinctive trumpet flowers, measuring 2-4 cm long, emerge in spectacular whorled clusters above uniquely fused leaf discs — a botanical feature that makes this species instantly recognizable. The blooms transition from bright orange buds to yellow-orange at maturity, creating a gradient of warm colors that illuminates woodland edges and garden trellises alike.

This remarkable native vine has been documented by explorers and botanists since Lewis and Clark’s expedition in 1804-1806, when they recorded it during their journey through the Pacific Northwest. Today, Western Honeysuckle serves as both an outstanding ornamental plant and a crucial component of native ecosystems, supporting pollinators, hummingbirds, and other wildlife while providing natural beauty that changes dramatically with the seasons.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Lonicera ciliosa |

| Family | Caprifoliaceae (Honeysuckle) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Climbing Vine |

| Mature Height | Vine |

| Growth Rate | Moderate |

| Sun Exposure | Partial Sun to Light Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Soil Type | Moist, well-drained; tolerates various soil types |

| Soil pH | 5.5–7.5 (slightly acidic to neutral) |

| Bloom Time | May – July |

| Flower Color | Orange-yellow, trumpet-shaped |

| Fruit | Translucent orange-red berries |

| Wildlife Value | Hummingbirds, native bees, songbirds |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 5–9 |

Identification

Western Honeysuckle is immediately recognizable by several distinctive features that set it apart from other vines in the Pacific Northwest. The most striking characteristic is its trumpet-shaped flowers, which appear in spectacular whorled clusters of 6-20 blooms positioned directly above pairs of uniquely fused leaves. These flowers measure 2-4 cm in length and display a beautiful gradient from bright orange buds to yellow-orange mature blooms, often with contrasting deeper orange at the flower mouth.

Leaves

The leaves are opposite, oval-shaped, and measure 4-10 cm in length. What makes them particularly distinctive is that the uppermost pair of leaves on each flowering stem are completely fused around the stem, forming a continuous disc or collar through which the stem appears to grow. This perfoliate leaf arrangement is a diagnostic feature of several native honeysuckles. The leaves are blue-green to gray-green on top with a slightly glaucous (waxy) appearance, and paler beneath. They have smooth margins without teeth or serrations.

Stems

Young stems are hollow, smooth, and often have a reddish or purplish tinge, especially when grown in full sun. The vine climbs by twining, typically reaching 10-20 feet in height when provided with suitable support. Older woody stems develop a light brown, fibrous bark that may peel in thin strips.

Flowers

The tubular flowers are the plant’s crowning glory, appearing from May through July in terminal clusters above the fused leaf discs. Each flower has five small lobes that spread outward from the tube opening, and the stamens and pistil extend prominently beyond the petals. The flowers face upward and outward, perfectly positioned for visiting hummingbirds and long-tongued bees.

Fruit

Following the flowers, small clusters of translucent orange-red berries develop, each less than 1 cm in diameter. While these berries are sometimes considered edible, they may cause digestive upset and are best left for wildlife. The berries ripen in late summer and are quickly consumed by birds.

Native Range

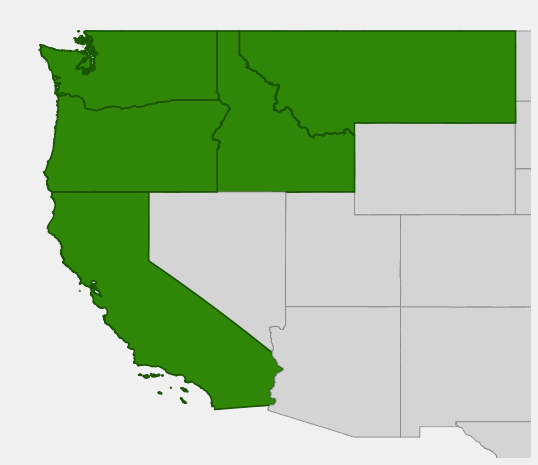

Western Honeysuckle is native to the temperate forests of the Pacific coast, with a natural range extending from southwestern British Columbia south through western Washington and Oregon to northern California, with populations also found in the northern Rocky Mountains of Idaho and Montana. This species thrives in the region’s characteristic Mediterranean climate, with wet winters and relatively dry summers.

In its native habitat, Western Honeysuckle typically grows in forest openings, along woodland edges, and in riparian areas where it receives dappled sunlight. It is commonly found climbing over shrubs and into the lower canopy of coniferous and mixed forests, where it creates vertical layers of habitat and food resources. The species shows remarkable adaptability to different forest types, from coastal temperate rainforests to drier inland mountain forests.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Western Honeysuckle: Western Oregon & Western Washington · Idaho, Eastern Oregon & Eastern Washington

Growing & Care Guide

Western Honeysuckle is an exceptionally rewarding native vine for Pacific Northwest gardens, offering spectacular flowers, wildlife value, and relatively low maintenance requirements once established. It adapts well to cultivation and can thrive in a variety of garden settings when its basic needs are met.

Light Requirements

This species performs best in partial sun to light shade, mimicking its natural forest edge habitat. In full sun, the vine may require more consistent moisture and can suffer from leaf scorch during hot summer weather. In deep shade, flowering will be reduced, though the foliage remains attractive. Morning sun with afternoon shade provides ideal conditions in most gardens.

Soil & Water

Western Honeysuckle prefers moist, well-drained soil but shows remarkable adaptability to different soil types including clay, loam, and sandy soils. It thrives in slightly acidic to neutral conditions (pH 5.5-7.5) but can tolerate more alkaline soils with adequate organic matter. Consistent moisture is important, especially during the establishment period and summer dry spells. A 2-3 inch layer of organic mulch helps retain soil moisture and suppress weeds.

While the species is somewhat drought-tolerant once established, it produces the most vigorous growth and abundant flowers when provided with regular water during the growing season. Avoid overwatering, as soggy conditions can lead to root rot.

Planting & Establishment

Plant Western Honeysuckle in early spring or fall for best establishment. Choose a location where the vine can climb naturally — a sturdy trellis, arbor, fence, or existing shrubs or small trees work well. Space plants 8-10 feet apart if using multiple vines to create coverage. Dig a planting hole twice as wide as the root ball and amend heavy clay soils with compost to improve drainage.

Young plants may take 2-3 years to become fully established and begin flowering prolifically. Be patient during this establishment period, as the vine is developing its root system and structural framework.

Support & Training

As a twining vine, Western Honeysuckle needs vertical support to climb effectively. It works beautifully on lattice panels, pergolas, arbors, or allowed to climb into small trees. The vine is not aggressive like some honeysuckles and won’t damage tree bark or structures with excessive twining pressure. Guide young growth toward the desired support structure and secure loosely with soft ties if needed.

Pruning & Maintenance

Pruning requirements are minimal. Remove dead, damaged, or weak growth in late winter or early spring before new growth begins. Light pruning after flowering can help maintain shape and encourage bushier growth. Unlike invasive honeysuckles, Western Honeysuckle rarely requires heavy pruning to control its spread.

The vine naturally develops a somewhat open, airy structure that showcases the flowers beautifully. Over-pruning can reduce flowering, so err on the side of minimal intervention.

Propagation

Western Honeysuckle can be propagated from softwood cuttings taken in late spring or early summer, or from semi-hardwood cuttings in late summer. Seeds require cold stratification and should be sown in fall or given 3 months of cold treatment before spring sowing. Plants grown from cuttings typically flower sooner than those grown from seed.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Western Honeysuckle is a keystone species in Pacific Northwest ecosystems, providing critical resources for a diverse array of wildlife throughout the growing season. Its ecological contributions extend far beyond its ornamental value, making it an essential component of native habitat gardens.

For Hummingbirds

The tubular orange flowers are specifically adapted for hummingbird pollination, with their color, shape, and nectar production perfectly matched to hummingbird feeding behavior. Rufous Hummingbirds, Anna’s Hummingbirds, and Calliope Hummingbirds are frequent visitors, often becoming quite territorial around blooming vines. The extended flowering period from May through July provides a reliable nectar source during the critical breeding season when hummingbirds have high energy demands.

The flowers produce copious nectar with a high sugar content, making Western Honeysuckle one of the most important native hummingbird plants in the Pacific Northwest. A single mature vine can support multiple hummingbird territories during peak bloom.

For Native Bees & Pollinators

While adapted primarily for hummingbird pollination, the flowers also attract long-tongued native bees, including bumblebees, mason bees, and leafcutter bees. The pollen is an important protein source for developing bee larvae, and the extended bloom period supports multiple generations of native bees throughout the summer.

For Birds

The translucent orange-red berries are consumed by a variety of songbirds including American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Swainson’s Thrushes, and various finches. The berries ripen in late summer when many birds are preparing for migration or building fat reserves for winter. The dense foliage also provides excellent nesting habitat for smaller songbirds.

For Other Wildlife

Small mammals including chipmunks and squirrels occasionally eat the berries, though they are not a primary food source. The vine’s climbing structure creates microhabitats for spiders, beneficial insects, and other small invertebrates that form the base of many food webs.

Ecosystem Services

Beyond direct wildlife support, Western Honeysuckle contributes to ecosystem health through soil stabilization on slopes, provision of organic matter through leaf drop, and creation of vertical habitat layers that increase biodiversity. The vine’s moderate growth rate and non-aggressive nature make it an ideal component of restoration plantings where native plant communities are being reestablished.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Western Honeysuckle has a rich history of use by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest. Various Coast Salish, Chinook, and other tribal nations utilized different parts of the plant for both practical and medicinal purposes. The inner bark was sometimes used to make twine, and the hollow stems were fashioned into small tubes for various applications.

Medicinally, various preparations of Western Honeysuckle were used traditionally to treat cold symptoms, as a mild sedative, and for other ailments. However, it’s important to note that the berries may be toxic if consumed in quantity and should not be eaten without proper knowledge and preparation.

The species was among the many plants documented by the Lewis and Clark Expedition during their journey through the Pacific Northwest in 1804-1806, highlighting its prominence in the region’s natural communities even in historical times.

Landscape Uses

Western Honeysuckle excels in numerous landscape applications, bringing both beauty and ecological function to Pacific Northwest gardens:

- Wildlife gardens — Essential for hummingbird habitat and native pollinator support

- Vertical accents — Beautiful climbing over arbors, pergolas, and trellises

- Natural screens — Provides privacy while supporting wildlife

- Woodland gardens — Perfect for naturalized forest edge plantings

- Native plant borders — Adds vertical interest to shrub and perennial combinations

- Restoration sites — Excellent for habitat restoration and erosion control on slopes

- Cut flower gardens — Stunning in arrangements, though flowers are short-lived

Companion Plants

Western Honeysuckle combines beautifully with other Pacific Northwest natives. Consider pairing with Red-flowering Currant (Ribes sanguineum) for extended hummingbird season, Mock Orange (Philadelphus lewisii) for fragrant white flowers, and native ferns like Sword Fern (Polystichum munitum) at the base. Wild Ginger (Asarum canadense) makes an excellent groundcover beneath the vine, while Oregon Grape (Mahonia aquifolium) provides structure and year-round interest.

Common Issues

Western Honeysuckle is remarkably pest and disease-resistant, which is one of its major advantages over non-native honeysuckles. Occasional aphid infestations may occur but rarely require treatment. In very dry conditions, spider mites can be problematic, but adequate watering and mulching typically prevent this issue.

The most common “problem” is simply impatience — the vine can be slow to establish and may not flower heavily until its third or fourth year. This is normal and results in a much more robust, long-lived plant.

Unlike invasive honeysuckles, Western Honeysuckle will not escape cultivation or become weedy, making it a responsible choice for eco-conscious gardeners.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Western Honeysuckle invasive like Japanese Honeysuckle?

No, Western Honeysuckle is a well-behaved native plant that doesn’t exhibit the aggressive spreading behavior of invasive honeysuckle species. It grows at a moderate pace and integrates well with other native plants without overwhelming them.

Can I eat the berries of Western Honeysuckle?

The berries are technically edible but not particularly tasty — they’re somewhat bitter and not considered a desirable food source. It’s best to leave them for wildlife, which depend on them for food. The berries are an important food source for many bird species.

How do I get Western Honeysuckle to bloom more heavily?

Western Honeysuckle blooms most prolifically in partial sun locations with good air circulation. Too much shade reduces flowering, while too much sun can stress the plant. Light pruning after flowering and adequate moisture during the growing season also promote better blooming.

Can Western Honeysuckle damage structures like other vines?

Western Honeysuckle is a relatively lightweight, twining vine that’s much less likely to cause structural damage than woody vines like English Ivy. However, it should still be monitored if grown on buildings and may need periodic pruning to prevent it from getting into gutters or under siding.

When is the best time to plant Western Honeysuckle?

Fall or early spring are the best planting times, allowing the plant to establish before the stress of summer heat. Make sure to provide adequate support structures if you want the vine to climb, as young plants need help finding their way to suitable supports.

Looking for a nursery that carries Western Honeysuckle?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: Oregon · Washington