Western White Pine (Pinus monticola)

Pinus monticola, commonly known as Western White Pine, Mountain White Pine, or Silver Pine, is one of the most magnificent native conifers of the Pacific Northwest and northern Rocky Mountains. A member of the Pinaceae (pine) family and the white pine group (five-needle pines), it is the state tree of Idaho — a fitting honor for a species that once dominated vast forests of the northern Rockies, producing some of the most valuable timber in the western United States. At its best, Western White Pine grows to 150 feet tall or more, with a straight, massive trunk and graceful, horizontal branches that sweep elegantly upward at their tips, creating a distinctive silhouette visible from great distances across mountain valleys.

Western White Pine grows best in full sun to part shade on moist, well-drained soils — conditions that prevail across the montane forests of northern Idaho, the Cascades, and the northern Sierras where this magnificent tree achieves its greatest development. Its five slender blue-green needles in bundles, long gracefully drooping cones (up to 14 inches), and smooth, silvery-gray bark on young trees make it one of the most beautiful of all western conifers. Historically, vast Western White Pine forests covered enormous areas of northern Idaho, northeastern Washington, and adjacent Montana — forests that supported the great lumber industry of the early 20th century and gave Idaho its moniker as the “White Pine State.”

Tragically, Western White Pine populations were decimated in the early 20th century by two catastrophes: commercial logging on a massive scale, and the introduction of white pine blister rust (Cronartium ribicola), a fungal disease that killed over 90% of Idaho’s white pine forest. Recovery has been slow and ongoing, with blister-rust-resistant seedlings now being widely planted in restoration efforts. Despite these challenges, Western White Pine remains a symbol of Idaho’s forest heritage and an important species for reforestation, restoration, and landscape planting wherever its natural habitat conditions can be met.

Identification

Western White Pine is a large to very large conifer, typically growing 100–150 feet tall at maturity (with exceptional specimens reaching 200+ feet) with a trunk 2–5 feet in diameter. The form is remarkably straight and symmetrical, with whorled horizontal branches that sweep upward slightly at their tips. Young trees have a narrowly pyramidal crown that broadens and becomes more irregular with age.

Bark

The bark is one of the most distinctive features: on young trees (up to 12–15 inches in diameter), the bark is smooth, thin, and ash-gray to silvery-gray, with a fine, almost plate-like texture. This smooth silvery bark is unique among western pines and gives the tree an elegant appearance. On old-growth trees, the bark breaks into large, roughly rectangular, cinnamon-brown scaly plates separated by narrow fissures — still distinctive but far different from the smooth young bark. The transition from smooth to plated bark can be dramatic over the tree’s lifespan.

Needles & Cones

The needles are borne in bundles of five — the defining characteristic of the white pine group — and are 2 to 4 inches long, slender, flexible, and blue-green in color with fine white lines (stomatal bloom) on all surfaces giving the foliage a slightly silvery-blue cast in bright sun. This blue-green needle color contrasts beautifully with the warm tones of other conifers in mixed forests.

The cones are among the longest of any western pine: 6–14 inches long, slender (1–1.5 inches wide), slightly curved, and pendant, hanging gracefully from the branch tips. The cone scales are thin and rounded, without prickles or hooks. Young cones are greenish-purple; mature cones turn tan-brown and are resinous. The seeds are winged and wind-dispersed. Seed production begins when trees are 10–20 years old and peaks in mature trees at 50–200 years.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Pinus monticola |

| Family | Pinaceae (Pine) |

| Plant Type | Evergreen Conifer (large tree) |

| Mature Height | 150+ ft (exceptional specimens to 200 ft) |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | Pollination: May – June (cones mature in second year) |

| Needle Color | Blue-green (5 needles per bundle) |

| Cone Length | 6–14 inches (among the longest of western pines) |

| Growth Rate | Moderate to fast (1–3 ft/year under good conditions) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 5–8 |

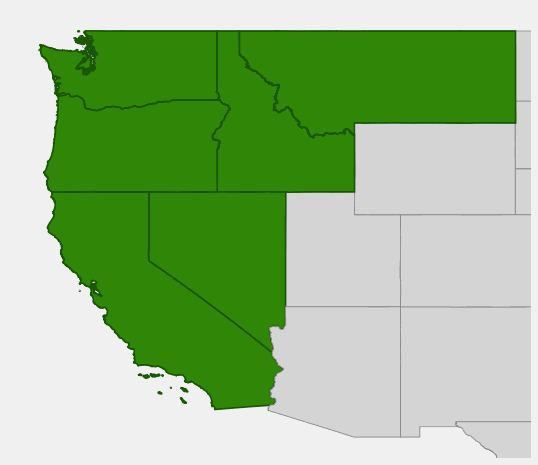

Native Range

Western White Pine is native to a discontinuous range in western North America, occurring in two main areas: the Pacific Coast ranges (Cascades and Klamath Mountains in Washington, Oregon, and northern California, and the Sierra Nevada in California and Nevada), and the northern Rocky Mountains (northern Idaho, northeastern Washington, northwestern Montana). The species is most abundant and achieves its greatest size in the moist, mild climate of northern Idaho, where the species was historically dominant. British Columbia and Alberta host populations in the northern extent of its range.

In the northern Rocky Mountains, Western White Pine grows in the western hemlock zone — the wettest forests east of the Cascades — where annual precipitation often exceeds 40–60 inches. These forests, which receive mild Pacific moisture tracked through the Columbia River Gorge, support an exceptionally diverse and productive forest community. Western White Pine grew as the most commercially important large tree in the northern Idaho panhandle and adjacent areas, forming vast old-growth forests that were the basis of the great early 20th-century lumber economy of the region.

The species grows from near sea level in coastal areas to elevations of 10,000 feet in the Sierra Nevada. In the Cascades, it typically grows at 3,000–7,000 feet elevation in mixed conifer forests with Western Red Cedar, Western Hemlock, Douglas Fir, and Grand Fir. In Idaho, it grows primarily at 2,000–6,000 feet on moist, north-facing slopes and in valley bottoms with adequate moisture. The tree is notably absent from dry, hot sites — it requires the consistently moist conditions provided by either coastal marine influence or mountain topography.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Western White Pine: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Western White Pine is a magnificent long-term landscape tree for sites with adequate moisture and space. It is a fast grower by conifer standards, adding 1–3 feet per year in favorable conditions, and can reach significant size within 20–30 years. The key considerations are site moisture, blister rust resistance, and giving the tree ample room to develop its full magnificent form.

Light

Western White Pine grows best in full sun to part shade. Young trees are moderately shade-tolerant and can establish beneath a partial canopy, but develop their best form and fastest growth in full sun with adequate moisture. Avoid deep shade, which stunts growth and reduces the tree’s long-term health. The tree naturally grows in both open and forest-edge conditions across its range.

Soil & Water

Western White Pine grows best in moist, well-drained soil — the conditions it naturally experiences in the moist hemlock-cedar forests of northern Idaho and the Cascades. It is not drought-tolerant and should not be planted in dry, hot locations without supplemental irrigation. Loamy to sandy-loamy soils with good drainage work best; the tree is sensitive to waterlogged soils. In gardens, deep, consistent watering during summer is essential, particularly in warmer, drier climates at the edge of its natural range. Mulching with 3–4 inches of bark or wood chip mulch helps retain soil moisture.

Planting Tips

Plant Western White Pine in spring from container stock. Choose a site with full sun and adequate moisture, away from buildings (this tree can reach enormous size). Give it at minimum 30–50 feet of clearance from structures in all directions — it will eventually need it. For forest garden settings, it naturalizes beautifully with Western Red Cedar, Grand Fir, and Western Hemlock. Plant blister-rust-resistant seedlings whenever available — these have been selected for genetic resistance to white pine blister rust and have significantly better long-term survival prospects.

Pruning & Maintenance

Western White Pine requires minimal pruning. Remove dead branches in late winter. Avoid heavy pruning of live branches — large wounds are slow to close and provide entry points for disease. The tree naturally self-prunes lower branches in forest conditions. Monitor for signs of blister rust infection (orange pustules on needles, cankers on branches and trunk) and remove infected branches promptly to slow the disease’s progression. In gardens, providing adequate air circulation around the crown reduces blister rust infection pressure.

Landscape Uses

Western White Pine is a long-term investment in landscape heritage:

- Large property forest specimen — one of the most majestic trees for large rural properties in the Pacific Northwest

- Reforestation and restoration — critical for restoring northern Rocky Mountain and Cascade forest ecosystems

- Wildlife habitat tree — seeds, cavities, and canopy support diverse forest wildlife

- Historic significance planting — recreating the character of the great Idaho white pine forests

- Windbreak or screening — fast-growing tall conifer for large-scale screening needs

- Mixed conifer garden — beautiful combination with Western Red Cedar, Larch, and Grand Fir

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Western White Pine is a keystone species in the northern Rocky Mountain and Pacific Northwest forest ecosystem, providing food, habitat, and structural diversity for a wide range of wildlife.

For Birds

The large seeds of Western White Pine are consumed by Clark’s Nutcrackers, Steller’s Jays, Stellar’s Jays, Cassin’s Finches, Red Crossbills, and White-winged Crossbills. Red Crossbills in particular are specialists on pine seeds, with their crossed bill tips uniquely adapted for prying open pine cone scales. The large trees also provide essential nesting habitat for forest raptors including Northern Goshawks, Red-tailed Hawks, and Ospreys, which nest in the large crowns. Pileated Woodpeckers excavate cavities in old or dead white pine snags, which are then used by secondary cavity nesters including owls, mergansers, and swallows.

For Mammals

Douglas Squirrels (Chickarees) and Red Squirrels are among the most important seed predators of Western White Pine, harvesting cones before they fully open and caching seeds in middens. Black Bears strip bark from young trees to eat the sweet inner cambium layer in spring — a behavior that can kill young trees and creates distinctive “bear scars” on surviving trees. Porcupines also eat the inner bark and cambium. White-tailed Deer, Elk, and Moose browse the lower branches. Mountain Beaver (Aplodontia rufa) harvests the branches for food caching.

For Pollinators

Western White Pine flowers are wind-pollinated, but the resin-rich pollen is collected incidentally by native bees foraging on the male strobili (pollen cones). The complex canopy structure of Western White Pine forests supports diverse insect communities — including many species of bark beetles, wood borers, and moth caterpillars — that are in turn important food sources for insectivorous birds.

Ecosystem Role

Western White Pine is a dominant overstory species in some of the most biodiverse forest ecosystems in the western United States. The northern Idaho hemlock-cedar-white pine forest type is one of the most structurally complex and wildlife-rich in the region. Old-growth Western White Pine forests supported enormous individual trees with cavities, snags, and downed logs that provided habitat for hundreds of species. The loss of over 90% of Idaho’s white pine forests to logging and blister rust represents one of the most significant ecological changes in the region’s history, and the restoration of blister-rust-resistant Western White Pine is a conservation priority for federal, state, and tribal land managers.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Western White Pine has deep cultural significance for the Indigenous peoples of the northern Rocky Mountains and Pacific Northwest. The Coeur d’Alene, Nez Perce, Kalispel, and other interior Salish peoples harvested the sweet inner bark (cambium) of Western White Pine in spring — scraping it from young trees with carved wooden tools and eating it fresh or drying it in strips for later use. The cambium is nutritious, somewhat sweet, and was an important emergency food and seasonal treat. The pitch and resin of the tree were used medicinally — applied to wounds to prevent infection, used in sweat lodge preparations, and burned as incense in ceremonies. The long, straight trunks were occasionally used for lodge poles and canoe making, though Western Red Cedar was preferred for the latter.

Western White Pine became Idaho’s state tree in 1935, at the height of the white pine lumber era, when the forests of northern Idaho were producing over 1 billion board feet of lumber annually. The wood of Western White Pine — soft, straight-grained, uniform in texture, and easy to work — was prized for construction, furniture, window frames, patterns, matches, and countless other applications. Idaho’s economy was built in significant part on white pine lumber, and towns like Sandpoint, Priest River, Potlatch, and Lewiston grew up around white pine mills. The Potlatch Forests company — later Potlatch Corporation — was one of the largest and most significant timber companies in the west, named for the ceremonial gift-giving tradition of Pacific Northwest tribes.

The ecological disaster of white pine blister rust — introduced to North America via infected nursery stock from Europe around 1910 — has been one of the most devastating biological invasions in forest history. Within decades, the fungus had killed the vast majority of mature Western White Pine across Idaho, Montana, and adjacent states. The USDA Forest Service began a decades-long program of selecting and breeding blister-rust-resistant Western White Pine seedlings, creating strains that survive at rates of 25–40% in areas with heavy rust pressure. Today, these resistant seedlings are used in large-scale reforestation efforts across the species’ range, slowly rebuilding what was lost. Idaho’s designation of Western White Pine as its state tree remains a statement of commitment to the recovery of this species and the forest heritage it represents.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is Western White Pine Idaho’s state tree?

Western White Pine was designated Idaho’s state tree in 1935 to honor the species’ immense importance to the state’s economy and forest heritage. At the time, Idaho’s white pine forests were among the most productive timberlands in North America, and the species was integral to the region’s identity. Despite the subsequent devastation of blister rust, Western White Pine remains the state tree as a symbol of Idaho’s forest history and the ongoing restoration effort.

What is white pine blister rust?

White pine blister rust (Cronartium ribicola) is a fungal disease introduced to North America from Asia via Europe around 1910. It affects all five-needle pines (white pines) and requires currant and gooseberry plants (Ribes spp.) to complete part of its life cycle. The disease kills trees by girdling branches and eventually the main trunk with cankers. It has killed over 90% of Idaho’s Western White Pine. Planting blister-rust-resistant seedlings is the most effective long-term management approach.

How large does Western White Pine get?

Western White Pine typically reaches 100–150 feet at maturity, with the largest specimens exceeding 200 feet and trunk diameters of 4–5+ feet. The all-time champion Western White Pine, found in the Pend Oreille National Forest in Washington, stands 219 feet tall. Growth rates are moderate to fast for a conifer — typically 1–3 feet per year in good conditions, slowing as the tree matures.

Can I grow Western White Pine in my yard?

Yes, if you have adequate space (50+ feet clearance) and moist, well-drained soil. Western White Pine is not suitable for small urban lots due to its eventual enormous size, but is excellent for large properties, acreages, and rural settings in the Pacific Northwest and northern Rocky Mountains. Use blister-rust-resistant seedlings from local seed sources for best long-term success.

How do I tell Western White Pine from Eastern White Pine?

Both are five-needle pines with long, slender cones, but Western White Pine (Pinus monticola) has slightly shorter needles (2–4 inches vs. 3–5 inches), narrower and often longer cones, and is native to the western United States and Canada. The two species do not overlap in range — Eastern White Pine is native east of the Great Plains. In gardens, Western White Pine tends to be slightly smaller at maturity in most settings, though both are large trees.