Western Redcedar (Thuja plicata)

Thuja plicata, commonly known as Western Redcedar, is one of the most magnificent and culturally significant trees of the Pacific Northwest. These towering evergreen giants can live over 1,000 years and reach heights of 100–175 feet, with massive trunks up to 23 feet in diameter. Despite its name, Western Redcedar is not a true cedar but a member of the cypress family (Cupressaceae), distinguished by its aromatic, rot-resistant wood and distinctive flat, scale-like foliage that creates graceful, drooping sprays.

Revered by Indigenous peoples as the “Tree of Life,” Western Redcedar provided virtually everything needed for survival — from the massive trunks that became ocean-going canoes and longhouses to the fibrous bark that was woven into clothing, baskets, and rope. The aromatic wood, naturally resistant to decay and insects, has made Western Redcedar one of the most valuable timber species in the world, prized for everything from construction lumber to cedar shingles and outdoor furniture.

In the wild, Western Redcedar creates some of North America’s most spectacular old-growth forests, forming cathedral-like groves where massive trunks rise from the forest floor like living pillars supporting a canopy hundreds of feet overhead. These ancient trees are ecological keystones, providing habitat for countless species while their shallow root systems help prevent soil erosion along streambanks and steep slopes. The species’ remarkable longevity and ability to reproduce through both seeds and vegetative means have allowed it to dominate Pacific Northwest forests for millennia.

For modern gardeners and landscapers, Western Redcedar offers unmatched grandeur and year-round beauty, though its eventual size requires careful siting. Young trees grow relatively slowly but steadily, eventually becoming living monuments that can serve as focal points for large properties, parks, and restoration projects. The species’ tolerance for wet soils and shade makes it valuable for challenging sites where many other trees struggle.

Identification

Western Redcedar is unmistakable among Pacific Northwest conifers, with distinctive characteristics that make identification straightforward even at a distance. Mature specimens develop the classic conical shape that gradually becomes more irregular and broad-crowned with age, creating the distinctive silhouette of ancient giants that dominate old-growth forests.

Size & Form

In optimal conditions, Western Redcedar can reach extraordinary dimensions — heights of 100–175 feet are common, with exceptional specimens reaching over 200 feet. The trunk diameter can reach 8–23 feet, with the largest recorded specimens approaching 30 feet in diameter. The massive trunk often develops distinctive buttressing at the base, creating dramatic fluted columns that can extend 15 feet or more up the trunk.

Young trees maintain a narrow, conical form with a single straight trunk and regular branching pattern. As they age, the crown broadens and becomes more irregular, often developing multiple tops after storm damage or other disturbances. The characteristic drooping branch tips create graceful, layered tiers that give mature trees their distinctive appearance.

Bark

The bark is thin, fibrous, and reddish-brown to gray-brown in color, peeling off in long, stringy strips. This fibrous bark is distinctive among Pacific Northwest conifers and was traditionally harvested by Indigenous peoples for cordage, clothing, and basketry. The bark furrows are relatively shallow, and the outer bark can be easily peeled away by hand, revealing the reddish inner bark beneath.

Foliage

The foliage consists of small, scale-like leaves arranged in opposite pairs along flattened branchlets, creating distinctive flat sprays that hang in graceful, drooping patterns. Each individual scale is about ⅛ inch long, dark green on top with white stomatal bands beneath. When crushed, the foliage releases a pleasant, aromatic fragrance that is distinctly different from other conifers.

The foliage arrangement creates a distinctive “flat” appearance when viewed edge-on, unlike the more cylindrical branchlets of other conifers. This flattened branching pattern allows maximum light capture in the shaded understory where young Western Redcedars often grow.

Cones

Western Redcedar produces small cones that are quite different from the large, woody cones of pines and firs. The seed cones are small, about ½ inch long, egg-shaped, and composed of 8–12 thin, leathery scales. They start green and mature to brown in the first year, opening to release tiny winged seeds. Pollen cones are even smaller, appearing as tiny reddish structures at branch tips in early spring.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Thuja plicata Donn ex D.Don |

| Family | Cupressaceae (Cypress) |

| Plant Type | Evergreen Coniferous Tree |

| Mature Height | 100–175 ft |

| Trunk Diameter | 8–23 ft (2.4–7 m) |

| Growth Rate | Slow to Moderate |

| Lifespan | 600–1,000+ years |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Soil Type | Moist, well-drained to wet; adaptable |

| Soil pH | 4.5–7.0 (acidic to neutral) |

| Cold Hardiness | USDA Zones 5–7 |

| Deer Resistant | Yes (aromatic foliage deters browsing) |

| Fire Resistance | Low (thin bark, shallow roots) |

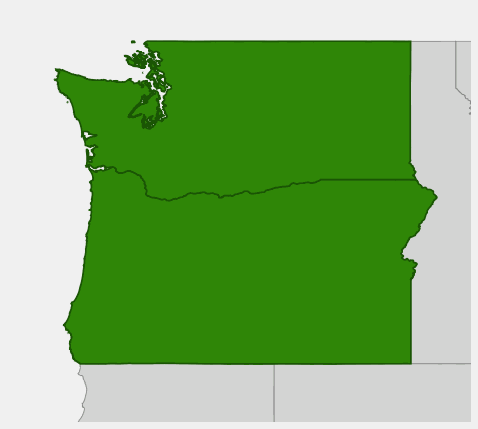

Native Range

Western Redcedar has a relatively narrow but ecologically significant native range that follows the cool, moist coastal and montane regions of western North America. The species ranges from southeastern Alaska south through coastal British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and into northwestern California, with inland populations extending into northern Idaho, western Montana, and small populations in southeastern British Columbia and southwestern Alberta.

Within this range, Western Redcedar shows strong preferences for specific microclimates and soil conditions. It thrives in areas with abundant moisture year-round — high rainfall, frequent fog, and high humidity are essential for optimal growth. The species is most abundant in the coastal fog belt and in moist valley bottoms and north-facing slopes where summer drought stress is minimized.

Elevation preferences vary by latitude and local climate, but Western Redcedar typically grows from sea level to about 3,000 feet in most of its range, reaching higher elevations in the warmer southern portions and lower elevations in the cooler northern areas. The species forms pure stands in some areas but more commonly grows in mixed stands with Douglas Fir, Western Hemlock, Sitka Spruce, and other Pacific Northwest conifers.

The remarkable old-growth forests dominated by Western Redcedar once covered millions of acres throughout the Pacific Northwest. These ancient forest ecosystems, with individual trees over 1,000 years old, represent some of the most productive and biodiverse temperate forests on Earth. Unfortunately, extensive logging has reduced old-growth Western Redcedar forests to small remnants, making the remaining groves some of the most precious and protected forest ecosystems in North America.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Western Redcedar: Western Oregon & Western Washington

Growing & Care Guide

Growing Western Redcedar successfully requires understanding its specific needs for moisture and space. While challenging in some respects due to its size and moisture requirements, the species is relatively straightforward to grow when sited properly, and the long-term rewards are extraordinary.

Light Requirements

Western Redcedar performs best in full sun to partial shade, though young trees tolerate considerable shade — a trait that allows them to regenerate in the understory of mature forests. In cultivation, trees grown in full sun develop the densest, most attractive foliage and maintain the classic conical form longest. Trees in partial shade may become more open and irregular but still grow vigorously.

Soil & Water Requirements

Consistent moisture is absolutely critical for Western Redcedar success. The species thrives in moist to wet soils and can tolerate seasonal flooding, making it valuable for rain gardens and low-lying areas where other trees struggle. However, it cannot tolerate drought and will decline rapidly in dry conditions.

Western Redcedar prefers acidic to neutral soils (pH 4.5–7.0) and grows best in rich, organic soils with good moisture retention. The species tolerates clay soils better than many conifers, particularly if drainage prevents standing water around the root zone. In sandy soils, incorporate generous amounts of organic matter and ensure consistent irrigation.

The shallow, fibrous root system means Western Redcedar is sensitive to soil compaction and root disturbance. Maintain a generous mulch zone around the tree to protect the root system and conserve soil moisture.

Planting & Establishment

Plant Western Redcedar in fall or early spring when moisture levels are naturally high. Choose sites with adequate space for the tree’s eventual size — allow at least 30–50 feet from structures and other large trees. Young trees establish relatively slowly but grow steadily once established, typically adding 12–24 inches per year under optimal conditions.

When planting, dig a hole twice as wide as the root ball but no deeper. The tree should be planted at the same depth it was growing in the container or nursery. Water thoroughly after planting and maintain consistent moisture for the first 2–3 years while the root system establishes.

Long-term Care & Maintenance

Established Western Redcedars require minimal care beyond ensuring adequate moisture. The species is naturally resistant to most pests and diseases, though it can be susceptible to root rot in poorly drained soils and may suffer from tip blight in stressful conditions.

Pruning is rarely necessary or recommended. The species maintains its natural form well, and pruning can damage the distinctive branch architecture. Remove only dead, damaged, or crossing branches, and never top or drastically prune mature specimens.

Landscape Uses

Western Redcedar’s impressive size and longevity make it suitable for specific landscape applications:

- Large property specimen — ultimate focal point for estates and parks

- Privacy screening — dense evergreen foliage provides year-round screening

- Riparian restoration — excellent for streambank stabilization

- Forest restoration — keystone species for recreating Pacific Northwest forests

- Memorial plantings — longevity makes them living monuments

- Wet area plantings — thrives where other trees struggle

Considerations & Challenges

The primary challenge with Western Redcedar is its eventual enormous size. Trees planted near structures, utilities, or property lines can become problematic as they mature. Plan for the tree’s full mature size and choose locations accordingly.

The species is not suitable for small residential lots, urban environments with limited moisture, or areas with extended dry periods. In climates outside its native range, Western Redcedar often struggles and may not develop properly.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Western Redcedar stands among the most ecologically valuable trees in North America, providing crucial habitat and resources for countless species throughout its range. The massive size, longevity, and complex structure of mature Western Redcedars create microhabitats that support extraordinary biodiversity.

For Birds

The dense, layered foliage provides excellent nesting sites for numerous bird species. Large raptors including Bald Eagles, Great Horned Owls, and Red-tailed Hawks often nest in the massive crowns of mature trees. Smaller birds such as Golden-crowned Kinglets, Brown Creepers, and various warblers nest in the dense foliage, while the seeds provide food for finches, siskins, and other seed-eating species.

The bark furrows and cavities in older trees provide nesting sites for woodpeckers, which in turn create cavities used by secondary cavity nesters including various owl species, nuthatches, and chickadees. The complex habitat structure from ground to canopy supports an incredible diversity of bird communities.

For Mammals

Large mammals including Black Bears, Roosevelt Elk, and Black-tailed Deer utilize Western Redcedar forests for shelter and thermal cover. The deer-resistant foliage means browse pressure is minimal, but the trees provide crucial cover habitat. Small mammals including flying squirrels, tree voles, and various bat species depend on the complex three-dimensional habitat created by mature Western Redcedar forests.

For Other Wildlife

The thick, furrowed bark provides habitat for numerous invertebrates, while epiphytic plants including mosses, ferns, and in some areas even other trees grow on the massive branches and trunks. This epiphytic garden supports additional communities of insects and small animals.

Salmon streams flowing through Western Redcedar forests benefit from the shade and large woody debris that fallen trees provide. The naturally rot-resistant wood creates long-lasting stream structure that provides salmon habitat for decades.

Ecosystem Role

As a dominant canopy species, Western Redcedar creates the physical structure of Pacific Northwest old-growth forests. The massive trees modify local climate, creating cooler, moister conditions that support shade-tolerant understory species. The shallow root systems help prevent soil erosion, particularly important along streams and on steep slopes.

When Western Redcedars eventually fall, they create “nurse logs” that provide growing substrates for the next generation of forest trees and support rich communities of decomposer organisms. This cycle of growth, death, and decay is fundamental to old-growth forest ecosystem function.

Cultural & Historical Uses

No tree holds greater cultural significance to Pacific Northwest Indigenous peoples than Western Redcedar. Known as the “Tree of Life” by many coastal tribes, Western Redcedar provided virtually everything necessary for survival and cultural expression. The Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, and numerous Coast Salish nations built entire civilizations around this remarkable tree.

The massive trunks were transformed into ocean-going canoes capable of carrying entire families on long journeys. Master carvers could fashion 60-foot canoes from single trees, creating vessels that were not just transportation but works of art. The same wood was used for constructing the massive plank houses that could shelter multiple families, with some structures reaching 100 feet in length.

Perhaps even more remarkably, Indigenous peoples learned to harvest the fibrous inner bark without killing the trees, using sophisticated techniques to peel strips of bark that would regenerate over time. This bark was processed into cordage stronger than rope, woven into clothing softer than cotton, and shaped into baskets so tightly woven they could hold water. Cedar bark clothing included everything from everyday work clothes to ceremonial regalia decorated with traditional designs.

Beyond material uses, Western Redcedar held deep spiritual significance. The tree appeared in creation stories, ceremonies, and traditional art. Cedar branches were used in purification ceremonies, while the aromatic wood was believed to have protective properties. The longevity and grandeur of ancient cedars made them sacred sites for many tribes.

European contact brought dramatic changes to these traditional relationships. The exceptional qualities of Western Redcedar wood — particularly its natural resistance to rot and insects — made it extremely valuable to the logging industry. Cedar shingles, siding, and lumber became major export products, leading to extensive harvesting of old-growth cedar forests throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Today, Western Redcedar remains an important timber species, though sustainable harvesting practices and greater awareness of the tree’s ecological and cultural value have changed management approaches. Contemporary Indigenous communities continue traditional uses while also leading efforts to protect remaining old-growth cedar forests. Modern applications include high-quality lumber for construction, cedar shingles and siding, outdoor furniture, and specialty products that take advantage of the wood’s natural durability.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take for Western Redcedar to reach mature size?

Western Redcedar is a slow-growing tree that may take 200–400 years or more to reach full maturity. However, trees can become impressive specimens in 50–100 years, reaching 60–100 feet tall. The species continues growing throughout its life, with the largest specimens being 800–1,000+ years old.

Can I grow Western Redcedar outside the Pacific Northwest?

Western Redcedar can be challenging to grow outside its native range due to its specific moisture and climate requirements. It may succeed in areas with similar cool, moist conditions, but typically struggles in hot, dry, or continental climates. Success is most likely in areas with high humidity and consistent moisture.

Is Western Redcedar suitable for small residential properties?

Generally no — Western Redcedar’s eventual enormous size makes it unsuitable for small lots. Trees can eventually reach 100–175 feet tall with massive canopies, potentially causing issues with structures, utilities, and neighboring properties. Consider smaller native conifers for residential landscapes.

How much water does Western Redcedar need?

Western Redcedar requires consistent, abundant moisture throughout the year. In dry climates, supplemental irrigation may be necessary, particularly during summer months. The species cannot tolerate drought and will decline rapidly in dry conditions. Plan for 1–2 inches of water per week during growing season.

Are there smaller cultivars of Western Redcedar available?

Yes, several dwarf and compact cultivars have been developed for landscape use, including ‘Atrovirens’, ‘Fastigiata’ (columnar form), and various dwarf selections. These maintain the attractive foliage and form while reaching more manageable sizes, though they still require abundant moisture.

What’s the difference between Western Redcedar and Eastern Redcedar?

Despite similar common names, these are completely different species. Western Redcedar (Thuja plicata) is native to the Pacific Northwest, has flat, scale-like foliage, and requires abundant moisture. Eastern Redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) is native to eastern North America, has needle-like juvenile foliage, and tolerates dry conditions. They’re not even closely related botanically.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Western Redcedar?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: Oregon · Washington