Cinnamonbark (Clethra acuminata)

Clethra acuminata, commonly known as Cinnamonbark, Mountain Sweet Pepperbush, or Mountain Pepper Bush, is a spectacular native deciduous shrub of the southeastern United States that deserves far wider recognition in native plant gardening. This member of the Clethraceae (White Alder) family produces some of the most intensely fragrant flowers in the native plant kingdom — twisted racemes of pure white, lily-of-the-valley-like blossoms that perfume the summer air with a sweet, spicy scent that can be detected from remarkable distances.

Growing naturally in the cool, moist ravines and stream valleys of the Appalachian Mountains, Cinnamonbark is a medium-sized shrub or small tree reaching 8 to 15 feet tall, with smooth reddish-brown bark that peels in thin strips — earning it the “cinnamonbark” name. The dark green, heavily serrated leaves provide excellent texture and form in the landscape, while the spectacular July and August flower display makes this shrub absolutely unforgettable. Each flower spike can contain dozens of small white flowers arranged in distinctive twisted or curved racemes that dance in the summer breeze.

Unlike its more common coastal cousin, Sweet Pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia), Cinnamonbark prefers the cooler mountain environments and is perfectly adapted to the challenging conditions of Appalachian slopes and hollows. Its exceptional drought tolerance once established, combined with its ability to thrive in partial shade, makes it an outstanding choice for naturalistic gardens, woodland edges, and challenging sites where few other flowering shrubs will perform reliably. The intensely fragrant flowers attract butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds, while the persistent seed capsules provide winter interest and food for birds.

Identification

Cinnamonbark typically grows as a multi-stemmed large shrub or occasionally a small single-trunked tree, reaching 8 to 15 feet (2.4–4.6 m) tall with a similar spread. The growth form is upright and somewhat open, creating an airy, naturalistic appearance that fits beautifully into woodland settings. In ideal conditions, mature specimens can occasionally reach heights of 18-20 feet, though this is uncommon in cultivation.

Bark

The bark is one of Cinnamonbark’s most distinctive features, particularly on mature stems. The outer bark is smooth and reddish-brown to cinnamon-colored, peeling away in thin, papery strips to reveal lighter inner bark — creating an attractive exfoliating pattern similar to that seen on birches or cherry trees. Young twigs are initially green to reddish-brown, becoming more distinctly cinnamon-colored with age. The bark has a slightly spicy, aromatic quality when crushed or bruised, contributing to the plant’s common name.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, deciduous, and arranged alternately along the stems. Each leaf is oval to elliptic, 3 to 6 inches (7.5–15 cm) long and 1.5 to 3 inches (3.8–7.6 cm) wide, with a sharply pointed tip (acuminate — hence the species name acuminata). The leaf margins are finely and sharply serrated with prominent teeth. The upper surface is dark green and somewhat glossy, while the underside is paler green with fine hairs along the veins. Leaves have distinct parallel veining and turn bright golden-yellow in autumn before dropping.

Flowers

The flowers are Cinnamonbark’s crown jewel — appearing in July and August in terminal and axillary racemes that are 3 to 8 inches (7.5–20 cm) long. What makes these flower clusters so distinctive is their twisted, curved appearance — the racemes don’t hang straight down but curve and spiral in graceful arcs. Each individual flower is small, about ¼ inch (6 mm) across, with five pure white petals, ten prominent white stamens, and a single pistil. The flowers have an intensely sweet, spicy fragrance that can perfume an entire garden and be detected from 50 feet or more away on still summer evenings.

Fruit

Following the flowers, Cinnamonbark produces small, dry capsules about ⅛ inch (3 mm) long that split open to release tiny seeds. The capsules are initially green, turning brown and persisting on the plant well into winter, adding textural interest to the bare winter stems. Each capsule contains numerous small seeds that are dispersed by wind and water.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Clethra acuminata |

| Family | Clethraceae (White Alder) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub / Small Tree |

| Mature Height | 8–15 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | July – August |

| Flower Color | Pure White |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 5–8 |

Native Range

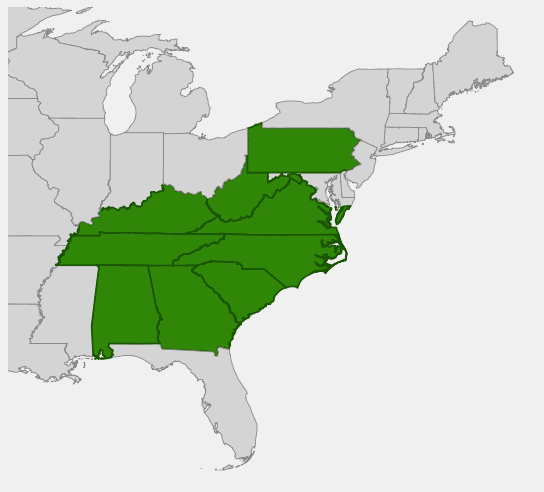

Cinnamonbark is native to the southeastern United States, with its range centered in the Appalachian Mountains and extending from southern Pennsylvania south to northern Georgia and Alabama. The species is most common in the mountains of North Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Tennessee, and eastern Kentucky, where it thrives in the cool, moist conditions of mountain ravines, stream valleys, and protected north-facing slopes.

In its native habitat, Cinnamonbark typically grows at elevations from 1,000 to 4,500 feet, preferring the cooler temperatures and higher moisture levels found at these mountain elevations. It is commonly found growing along mountain streams, in moist woodland hollows, and on slopes where water seepage keeps soils consistently moist but not waterlogged. The species often grows in association with other Appalachian natives such as Rhododendron, Mountain Laurel, Hemlock, and various ferns.

Unlike the more widespread Sweet Pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia), which prefers coastal plain conditions, Cinnamonbark is specifically adapted to the cooler, more mountainous conditions of the interior Southeast. This adaptation makes it an excellent choice for gardeners in USDA zones 5-8 who want the spectacular flowers and fragrance of a Clethra but need a species better suited to inland conditions.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Cinnamonbark: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Cinnamonbark is surprisingly easy to grow once you understand its preferences, making it an excellent choice for gardeners looking to add spectacular summer fragrance to their landscapes. While it has a reputation for being challenging, this is largely because it’s often grown in inappropriate conditions — give it the cool, moist environment it craves, and it will thrive with minimal care.

Light

Cinnamonbark performs best in partial shade to full sun, with morning sun and afternoon shade being ideal in warmer climates. In its native mountain environment, it often grows in dappled light beneath taller trees, so it’s well-adapted to less-than-full-sun conditions. In cooler climates (zones 5-6), it can handle more direct sun, while in warmer areas (zones 7-8), some afternoon shade helps prevent stress during hot summers. Avoid deep shade, as this will reduce flowering significantly.

Soil & Water

The key to success with Cinnamonbark is providing consistently moist but well-drained soil. It prefers rich, organic soils with a pH range of 4.5-6.5 (acidic to slightly acidic). The soil should be deep and humus-rich — think of the leaf-mold-rich soils of mountain stream valleys. Good drainage is crucial; while the plant needs consistent moisture, it cannot tolerate waterlogged conditions. Incorporate plenty of compost, aged leaf mold, or other organic matter when planting to improve both moisture retention and drainage.

Planting Tips

Plant Cinnamonbark in spring or fall when temperatures are cool and moisture levels are naturally higher. Choose a protected site away from drying winds, and ensure the planting area receives adequate water during establishment. Dig a planting hole twice as wide as the root ball but no deeper, and backfill with amended native soil. Water thoroughly after planting and apply 2-3 inches of organic mulch to conserve moisture and keep roots cool. Space plants 8-10 feet apart for a naturalistic grouping.

Pruning & Maintenance

Cinnamonbark requires minimal pruning. Remove any dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter before new growth begins. If the shrub becomes too large or ungainly, it can be renewal pruned by cutting the oldest stems to ground level — new growth will emerge from the base. Avoid heavy pruning, as this can reduce flowering for a season or two. The plant has no significant pest or disease problems and is naturally resistant to deer browsing due to the bitter compounds in its foliage.

Landscape Uses

Cinnamonbark’s spectacular summer flowering makes it valuable in many garden settings:

- Woodland gardens — naturalistic plantings beneath taller trees

- Stream-side plantings — excellent for moist areas near water features

- Fragrance gardens — the intense summer perfume is unmatched

- Wildlife gardens — attracts butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds

- Foundation plantings — provides seasonal interest and privacy screening

- Mixed native borders — combines well with other Appalachian natives

- Naturalized areas — excellent for low-maintenance naturalistic landscapes

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Cinnamonbark provides significant ecological benefits, supporting a wide variety of native wildlife throughout the growing season and beyond.

For Birds

The persistent seed capsules of Cinnamonbark provide food for numerous small songbirds through fall and winter, including finches, chickadees, and titmice. The dense branching structure offers excellent nesting sites for small birds, while the summer insects attracted to the flowers provide protein-rich food for insectivorous birds during the critical breeding season. Many birds also use the exfoliating bark strips as nesting material.

For Mammals

While deer typically avoid Cinnamonbark due to the bitter compounds in its leaves, small mammals such as chipmunks and squirrels may eat the seeds. The dense shrub structure provides cover and shelter for various small woodland mammals, creating important habitat in the understory layer of forest ecosystems.

For Pollinators

The intensely fragrant summer flowers are magnets for a wide variety of pollinators. Native bees, including bumblebees and solitary bees, are frequent visitors, along with honeybees when present. The flowers also attract butterflies — particularly those species that are active during the day in summer woodland environments. Hummingbirds visit the flowers regularly, drawn by both the nectar and the abundant insects that the flowers attract. The long flowering period (often 4-6 weeks) provides a reliable nectar source during the peak of summer when many other woodland plants have finished blooming.

Ecosystem Role

In its native Appalachian habitat, Cinnamonbark serves as an important understory component, helping to create the layered structure that makes temperate deciduous forests so biodiverse. The plant’s ability to thrive in partial shade means it can grow beneath taller canopy trees, utilizing available light and creating habitat niches for wildlife that prefer intermediate light levels. Its extensive root system helps stabilize soil on slopes and stream banks, contributing to watershed health and erosion control.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Cinnamonbark has a rich history of use by Indigenous peoples of the southeastern United States, particularly the Cherokee and other tribes of the Appalachian region. The aromatic bark was traditionally used in various medicinal preparations, though specific historical uses have been less documented than those of its coastal cousin, Sweet Pepperbush. The intense fragrance of the flowers made the plant valuable for ceremonial and spiritual purposes, with some tribal traditions incorporating the flowering branches into summer rituals and celebrations.

Early European settlers were immediately struck by the plant’s incredible fragrance and often planted it near cabins and homesteads to perfume the summer air. The common name “cinnamonbark” reflects the aromatic quality of the exfoliating bark, which when crushed or bruised releases a spicy, cinnamon-like scent. Some settlers attempted to use the bark as a spice substitute, though it proved too bitter for most culinary applications.

In modern times, Cinnamonbark has gained recognition among native plant enthusiasts and fragrance gardeners, though it remains less commonly cultivated than many other native shrubs. Horticultural interest has grown significantly in recent years as gardeners seek alternatives to non-native flowering shrubs and as the native plant movement has emphasized the importance of preserving and utilizing regional flora. Some perfumers and aromatherapy practitioners have shown interest in the essential oils that can be extracted from both the flowers and bark, though commercial production remains limited.

The plant has also found use in ecological restoration projects, particularly in efforts to restore degraded Appalachian stream valleys and mountain slopes. Its ability to thrive in challenging conditions while providing exceptional wildlife value has made it a species of choice for restoration professionals working in the southeastern mountains. Research into its potential for erosion control and riparian buffer restoration continues to expand its conservation value beyond its ornamental qualities.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does Cinnamonbark differ from Sweet Pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia)?

While both are members of the Clethra genus, Cinnamonbark is adapted to mountain conditions and has twisted, curved flower racemes, while Sweet Pepperbush prefers coastal plain conditions and has straight, upright flower spikes. Cinnamonbark is also more cold-hardy and drought-tolerant once established, and its flowers have an even more intense fragrance.

Is Cinnamonbark difficult to grow?

Cinnamonbark has a reputation for being challenging, but this is usually because it’s grown in inappropriate conditions. Given consistently moist, well-drained acidic soil and partial shade, it’s actually quite easy to grow and maintain. The key is replicating the cool, moist conditions of its native mountain habitat.

When is the best time to plant Cinnamonbark?

Plant in early fall (September-October) or early spring (March-April) when temperatures are cool and natural moisture levels are higher. Avoid planting during hot summer months or when the ground is frozen. Fall planting is often preferred as it allows the root system to establish before the stress of the following summer.

Will Cinnamonbark attract too many bees to my garden?

While the intensely fragrant flowers do attract many pollinators including bees, this is actually a benefit for garden health and biodiversity. The bees are focused on collecting nectar and pollen and are generally non-aggressive around the flowers. Many gardeners specifically plant Cinnamonbark to support native bee populations.

How long does it take for Cinnamonbark to reach flowering size?

Young plants typically begin flowering in their second or third year after planting, though the flower display becomes more spectacular as the plant matures. Full flowering potential is usually reached by the fifth or sixth year, when plants have developed the mature branching structure needed to support abundant flower production.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Cinnamonbark?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina