Rosinweed (Silphium integrifolium)

Silphium integrifolium, commonly known as Rosinweed or Wholeleaf Rosinweed, is a robust perennial wildflower native to the tallgrass prairies and open woodlands of central North America. A member of the Asteraceae (sunflower) family, this striking plant produces clusters of bright yellow, daisy-like flowers from mid to late summer that are magnets for pollinators and add vivid color to any native landscape. The common name “Rosinweed” comes from the resinous sap that oozes from broken stems and leaves — a characteristic shared with its close relatives in the genus Silphium, including Cup Plant and Compass Plant.

Growing 2 to 6 feet tall with stiff, upright stems and rough, sandpapery leaves arranged in opposite pairs, Rosinweed is a plant built for the harsh conditions of the Great Plains. Its deep taproot — which can extend more than 14 feet into the soil — gives it remarkable drought tolerance and makes it an anchor species in prairie restorations. Once established, Rosinweed is extraordinarily long-lived, with some plants persisting for decades in undisturbed prairies.

Beyond its ornamental appeal and ecological value, Rosinweed has recently attracted significant attention from agricultural researchers as a potential new perennial oilseed crop. Under the name “Silphium,” it is being developed as a sunflower alternative that requires no annual planting, reduces erosion, and supports pollinators — making it one of the few native prairie plants on the frontier of modern agriculture. For home gardeners and restoration practitioners in the Dakotas and across the Great Plains, Rosinweed remains one of the most rewarding and resilient native wildflowers to grow.

Identification

Rosinweed is a stout, herbaceous perennial that grows from a thick, woody rootstock. Plants typically reach 2 to 6 feet (0.6–1.8 m) in height, with one or several erect, rough-hairy stems branching near the top. The overall appearance is robust and somewhat coarse, with an upright, columnar growth habit that gives prairie plantings a strong vertical accent.

Leaves

The leaves are one of Rosinweed’s most distinctive features. They are opposite (arranged in pairs along the stem), sessile (lacking stalks, attached directly to the stem), and have a rough, sandpapery texture on both surfaces due to dense, short, stiff hairs. Each leaf is lance-shaped to broadly ovate, 3 to 6 inches (7–15 cm) long and 1 to 3 inches (2.5–7 cm) wide, with smooth to slightly toothed margins. Unlike its cousin the Cup Plant (Silphium perfoliatum), whose leaf bases fuse around the stem to form cups, Rosinweed’s leaves have bases that clasp or narrowly attach to the stem without forming water-holding structures. The foliage is dark green and remains attractive through the growing season.

Flowers & Fruit

The flower heads are classic daisy-like composites, 1.5 to 3 inches (4–7 cm) across, with 15 to 25 bright yellow ray florets surrounding a central disk of darker yellow to brownish disk florets. Unlike many sunflower relatives, in Silphium species it is the ray florets that produce seeds rather than the disk florets — an unusual trait in the sunflower family. The flower heads are borne in loose, open clusters (corymbs) at the tops of branching stems. Bloom time extends from July through September, with peak flowering in August. The seeds (achenes) are flattened, winged, and about ½ inch long, ripening in late September through October.

Roots

Rosinweed develops an impressive deep taproot system that can penetrate more than 14 feet (4.3 m) into the soil, along with a network of lateral roots. This massive root system is key to the plant’s drought tolerance and longevity. When the stem or leaves are broken, they exude a sticky, resinous sap with a distinctive turpentine-like fragrance — the source of the common name “Rosinweed.” Indigenous peoples and early settlers chewed this dried sap as a natural chewing gum.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Silphium integrifolium |

| Family | Asteraceae (Sunflower / Aster) |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous Perennial Wildflower |

| Mature Height | 2–6 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | July – September |

| Flower Color | Bright Yellow |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–8 |

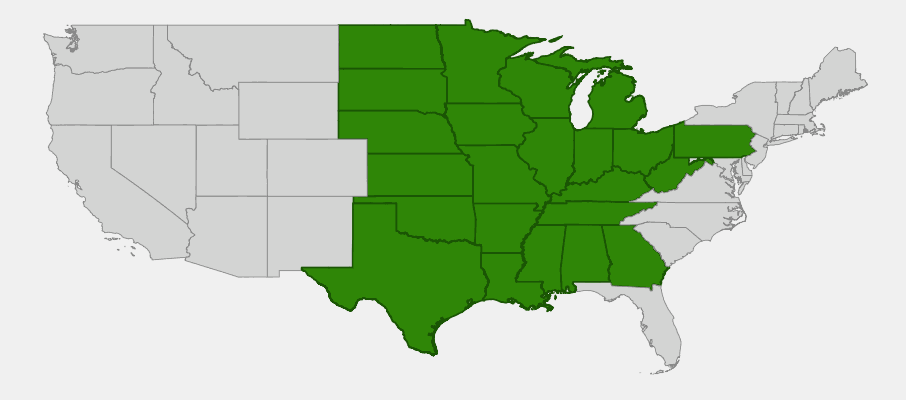

Native Range

Rosinweed is native to the tallgrass prairie region of central and eastern North America, ranging from the Dakotas and Minnesota south through the Great Plains states to Texas and eastward to Ohio, Pennsylvania, and the upper South. Its core range closely follows the historic extent of the tallgrass prairie ecosystem, with the greatest abundance in the states from Kansas and Nebraska east to Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio.

In its natural habitat, Rosinweed grows in tallgrass prairies, open meadows, savannas, and the edges of open woodlands. It is most common on mesic (moderately moist) to dry-mesic prairie soils, often in association with Big Bluestem, Indian Grass, Compass Plant, and other classic tallgrass prairie species. It tolerates a range of soil types from deep loams to rocky, limestone-derived soils, and can be found from lowland prairies to upland ridge prairies.

While Rosinweed was once abundant across millions of acres of unplowed prairie, habitat loss from agriculture has dramatically reduced native populations. Today, Rosinweed persists in prairie remnants, along railroad rights-of-way, in old cemeteries, and in restoration plantings. It is not considered endangered at the federal level but is uncommon in many parts of its range where prairie habitat has been converted to cropland.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Rosinweed: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Rosinweed is one of the easiest and most rewarding prairie wildflowers to grow, requiring minimal care once established. Its deep taproot makes it remarkably self-sufficient — tolerating drought, heat, wind, and cold that would stress many garden plants. The key to success is providing full sun and well-drained soil, then exercising patience during the establishment period.

Light

Rosinweed is a full-sun plant through and through. It requires at least 6 hours of direct sunlight daily and performs best with 8 or more hours. In too much shade, plants become leggy, flop over, and produce few flowers. On prairie sites, it naturally occupies open, unshaded positions where it can access full overhead light. Choose your sunniest garden spot for Rosinweed.

Soil & Water

This prairie native thrives in average, well-drained soils and is adaptable to a range of soil types including clay, loam, and rocky or gravelly substrates. It tolerates both slightly acidic and alkaline soils (pH 5.5–7.5). Once established, Rosinweed’s deep taproot provides excellent drought tolerance — supplemental watering is rarely needed after the first growing season. Avoid soggy or poorly drained sites, which can promote root rot. In the garden, moderate watering during the first year helps the taproot establish, after which the plant is largely self-sufficient.

Planting Tips

Rosinweed can be grown from seed or transplanted from container stock. Seed requires 60 days of cold-moist stratification for good germination — fall sowing directly outdoors naturally provides this. If spring sowing, stratify seeds in a moist paper towel in the refrigerator for 8–10 weeks before planting. Sow seeds ¼ inch deep. When transplanting, choose small container plants and plant in spring or early fall. Space plants 2–3 feet apart. Be patient: Rosinweed typically spends its first 1–2 years developing its massive root system and may not flower until the second or third year.

Pruning & Maintenance

Rosinweed requires virtually no maintenance. Leave spent flower stalks standing through winter — they provide seeds for birds and visual interest in the dormant landscape. Cut back old stems in early spring before new growth emerges. The plant does not need dividing and resents root disturbance due to its deep taproot. It is rarely bothered by pests or diseases. In very rich, heavily watered garden soils, plants may grow excessively tall and flop; in such cases, cutting plants back by one-third in late May (the “Chelsea chop”) produces shorter, sturdier stems.

Landscape Uses

Rosinweed’s versatility and toughness make it valuable in many settings:

- Prairie restoration — a keystone forb in tallgrass prairie seed mixes

- Pollinator gardens — long bloom season attracts diverse bees and butterflies

- Perennial borders — provides bold, late-summer yellow color

- Meadow gardens — naturalizes beautifully with native grasses

- Conservation plantings — deep roots prevent erosion and build soil

- Rain gardens — tolerates occasional wet periods while thriving in dry spells

- Cut flowers — long-lasting in arrangements

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Rosinweed is one of the most ecologically valuable wildflowers of the tallgrass prairie, providing food and habitat resources across multiple trophic levels and through much of the growing season.

For Birds

American Goldfinches are especially fond of Rosinweed seeds and are frequently seen perching on the flower heads in late summer and fall, extracting the large, nutritious achenes. Other seed-eating birds including sparrows, juncos, and native finches also utilize the seeds. The tall, sturdy stems provide perching sites for flycatchers and other insectivorous birds that hunt from elevated positions over the prairie. Leaving stems standing through winter provides continued foraging opportunities.

For Mammals

White-tailed deer occasionally browse the young foliage in spring but generally leave mature plants alone due to the rough leaf texture. Small mammals such as prairie voles and mice may use the base of large clumps for cover. The resinous sap was historically chewed by both Indigenous peoples and European settlers as a natural chewing gum — a use that earned the genus its common name.

For Pollinators

Rosinweed is a pollinator powerhouse. Its extended bloom period from July through September provides critical late-season nectar and pollen when many other prairie flowers have finished blooming. Numerous bee species visit the flowers, including bumble bees, sweat bees, mining bees, and leaf-cutter bees. Various butterfly species — including Monarchs, Painted Ladies, and fritillaries — feed on the nectar. Soldier beetles, hover flies, and predatory wasps are also frequent visitors, contributing to natural pest control in the garden.

Ecosystem Role

Rosinweed’s massive root system is an ecological powerhouse beneath the soil surface. The deep taproot creates macropores that improve water infiltration, while the extensive lateral root network binds soil and prevents erosion. As roots die and decompose, they contribute substantial organic matter deep in the soil profile, building the famously rich prairie soils. Above ground, the robust stems and dense foliage add structural diversity to prairie plantings. Rosinweed is also being researched as a perennial oilseed crop — its seeds contain 15–25% oil with a fatty acid profile similar to sunflower oil, and the Land Institute in Kansas has been developing domesticated varieties since 2000.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Rosinweed and its relatives in the genus Silphium have a long history of human use across the Great Plains and Midwest. The most widespread traditional use centered on the plant’s distinctive resinous sap. When stems are broken, they exude a sticky, amber-colored resin that dries into a pliable, gum-like substance. Multiple Indigenous nations — including the Pawnee, Omaha, and other Plains tribes — collected and chewed this dried resin as a natural chewing gum, a practice that was later adopted by European settlers and early frontiersmen. Some historians believe that the widespread chewing of Silphium resin by children on the frontier may have helped inspire the development of commercial chewing gum in the mid-1800s.

Several Indigenous nations also used Rosinweed medicinally. Root preparations were used by the Meskwaki (Fox) people to treat various ailments, and the resin was applied to wounds as a natural antiseptic poultice. The Cheyenne reportedly used the dried root as a treatment for stomach complaints. In prairie ecosystems, the presence of Rosinweed was often used as an indicator of high-quality, unplowed prairie — a sign that the land had never been turned by a plow, since the deep taproot cannot survive conventional tillage.

In modern times, Rosinweed has taken on new significance as a potential crop plant. The Land Institute in Salina, Kansas, has been working since 2000 to domesticate Silphium integrifolium as a perennial oilseed crop, marketed under the trade name “Silphium.” Because Rosinweed is perennial, requires no annual planting, has deep roots that prevent erosion, supports pollinators, and produces seeds rich in edible oil, it represents a promising model for sustainable agriculture. Breeding programs have already developed varieties with significantly larger seeds and higher oil content, and trial plantings are underway across the Midwest. This transformation from wild prairie flower to potential crop plant makes Rosinweed one of the most exciting native species in modern agricultural research.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Rosinweed the same as Cup Plant or Compass Plant?

No, though they are closely related. All three belong to the genus Silphium and share the characteristic resinous sap. Rosinweed (S. integrifolium) has opposite, sessile leaves with smooth margins. Cup Plant (S. perfoliatum) has opposite leaves that fuse at the base to form water-holding cups around the stem. Compass Plant (S. laciniatum) has deeply lobed basal leaves that tend to orient north-south.

How long does it take Rosinweed to bloom from seed?

Rosinweed typically takes 2–3 years to produce its first flowers from seed. During the first 1–2 years, the plant focuses on developing its massive taproot system. This patience pays off — once established, Rosinweed blooms reliably for decades with no replanting needed.

Can you really chew Rosinweed resin like gum?

Yes! The dried resin from broken stems was historically used as natural chewing gum by both Indigenous peoples and European settlers. It has a mildly resinous flavor. To try it, break a stem in summer, let the sap dry for a day, then peel off the hardened resin. It softens in the mouth much like commercial gum.

Will Rosinweed spread aggressively in my garden?

No. Unlike some prairie plants, Rosinweed does not spread by rhizomes or runners. It grows from a single deep taproot and stays in place. It may self-seed modestly, but seedlings are easy to transplant or remove. It is not considered invasive in any setting.

Is Rosinweed deer resistant?

Rosinweed has moderate deer resistance. The rough, sandpapery leaf texture deters most browsing on mature plants, though deer may nibble young spring growth. In areas with heavy deer pressure, protection during the first year of establishment is recommended. Once the plant reaches its full robust size, deer damage is typically minimal.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Rosinweed?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota