Fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium)

Epilobium angustifolium (syn. Chamaenerion angustifolium), commonly known as Fireweed, Rosebay Willowherb, or Great Willowherb, is a spectacular native perennial wildflower that has earned its place as one of North America’s most recognizable and ecologically important plants. This member of the Onagraceae (evening primrose) family is famous for its remarkable ability to rapidly colonize disturbed areas, particularly burned forest clearings, where it creates stunning displays of magenta-pink flowers that can stretch for miles.

Despite being listed as “White Fireweed” in some regional plant lists, this species typically produces vibrant pink to magenta flowers, not white ones. The confusion may arise from occasional white-flowered forms or from confusion with other willowherb species. The plant’s most distinctive characteristic is its dramatic height — reaching 3 to 8 feet tall — and its long, showy spikes of four-petaled flowers that bloom from bottom to top throughout the summer months.

Fireweed is particularly valued for its exceptional ecological role as a pioneer species in forest succession and its importance to pollinators, especially in northern and mountainous regions where it often dominates post-fire landscapes. The plant produces abundant nectar and is a crucial food source for numerous butterfly species, bees, and other pollinators. Its seeds, equipped with silky white hairs, disperse on the wind for miles, allowing it to quickly establish in suitable habitats.

Identification

Fireweed is unmistakable when in bloom, forming tall, sturdy stems topped with elongated spikes of showy pink to magenta flowers. The plant grows from deep, spreading rhizomes and can form extensive colonies over time, creating the dramatic natural displays for which it’s famous.

Stems & Growth Form

The stems are tall, robust, and unbranched, typically growing 3 to 8 feet in height, though exceptional specimens in ideal conditions can reach 9 feet or more. Stems are smooth, slightly ridged, and often reddish-tinged, especially near the base and nodes. The plant grows in an upright, columnar fashion, with multiple stems often emerging from the same rhizome system to create dense stands.

Leaves

The leaves are lanceolate (lance-shaped), 2 to 6 inches long and ½ to 1½ inches wide, arranged alternately along the stem in a spiral pattern. Each leaf is entire (smooth-margined) or very finely toothed, with prominent parallel veins running from the midrib to the leaf margin. The upper surface is dark green and smooth, while the underside is paler and may have a slight whitish or bluish cast. Leaves are sessile (without petioles) and taper to pointed tips.

Flowers & Fruit

The flowers are Fireweed’s most spectacular feature — arranged in long, dense, terminal racemes (spikes) that can be 4 to 16 inches long. Individual flowers are about 1 inch across with four rounded, pink to magenta petals (occasionally white), four sepals, eight prominent stamens, and a distinctive four-lobed stigma that resembles a small cross. The flowers bloom sequentially from bottom to top over several weeks, extending the blooming period from mid-summer into early fall.

The fruit is a long, narrow capsule (2 to 3 inches) that splits open to release numerous small seeds, each equipped with a tuft of long, silky white hairs that allow them to be carried great distances by wind. This efficient dispersal mechanism is key to Fireweed’s success as a colonizing species. The opening seed pods create additional visual interest in late summer and fall.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Epilobium angustifolium (syn. Chamaenerion angustifolium) |

| Family | Onagraceae (Evening Primrose) |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous Perennial |

| Mature Height | 3–8 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | July – September |

| Flower Color | Pink to magenta |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–8 |

Native Range

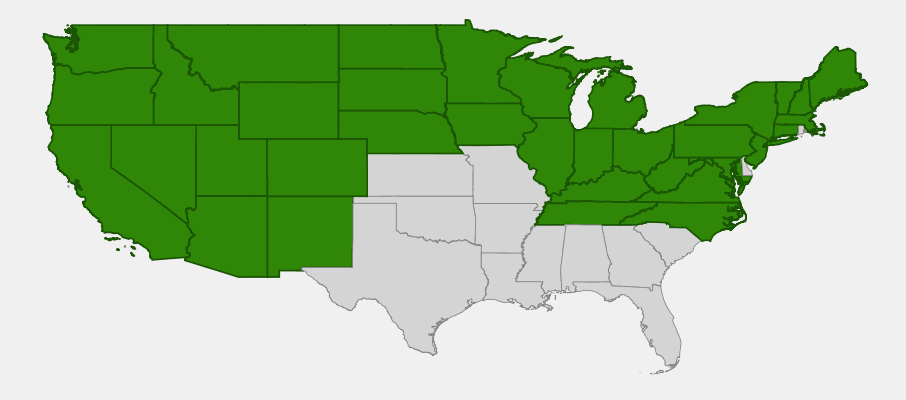

Fireweed has one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American wildflower, spanning virtually the entire continent from Alaska to Mexico and from the Pacific to the Atlantic. This remarkable distribution reflects the plant’s adaptability to diverse climatic conditions and its ecological role as a pioneer species capable of quickly colonizing disturbed habitats across multiple biomes.

The species is most abundant in the northern and mountainous regions of North America, where it reaches its greatest ecological significance in boreal forests, montane meadows, and alpine zones. It extends throughout Alaska and most of Canada, south through the western mountains to California and New Mexico, across the northern tier of states to New England, and south along the Appalachian Mountains. In these cooler regions, Fireweed often forms the dominant vegetation in post-fire landscapes.

While Fireweed’s range extends into warmer regions, it becomes increasingly restricted to higher elevations and cooler microsites as latitude decreases. This temperature sensitivity explains its common association with mountain meadows, forest clearings, and other open habitats where cooler conditions prevail. The plant’s remarkable ability to disperse via wind-blown seeds allows it to rapidly colonize suitable habitats across vast distances.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Fireweed: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Fireweed is generally easy to grow but can be somewhat challenging to establish in traditional garden settings due to its preference for disturbed soils and its tendency to spread aggressively once established. Understanding its natural ecology is key to successful cultivation and management in landscape settings.

Light

Fireweed requires full sun to perform at its best, thriving in open areas with at least 6-8 hours of direct sunlight daily. In its native habitat, it colonizes clearings, burned areas, and open meadows where light competition is minimal. While it can tolerate light shade, flowering will be reduced and stems may become weak and prone to flopping. The plant’s preference for full sun makes it ideal for sunny wildflower meadows and naturalistic plantings.

Soil & Water

One of Fireweed’s most distinctive characteristics is its preference for disturbed, mineral-rich soils rather than rich, organic garden soils. It thrives in sandy, rocky, or gravelly soils with good drainage and performs particularly well in soils with exposed mineral content, such as those found after fires or construction disturbance. The plant is remarkably drought-tolerant once established but appreciates moderate moisture during the growing season. Avoid heavy fertilization, which can cause excessive vegetative growth at the expense of flowering.

Planting Tips

Fireweed can be challenging to establish from transplants but grows readily from seed. Sow seeds in fall or stratify for 2-3 months before spring planting. The tiny seeds need light to germinate, so barely cover them with soil. For best results, create conditions that mimic natural disturbance: scrape away organic matter to expose mineral soil, or plant in sandy, well-draining areas. Space plants 2-3 feet apart, though note that established plants will spread via rhizomes to form colonies.

Pruning & Maintenance

Fireweed requires minimal maintenance once established. Deadhead spent flower spikes to prevent excessive self-seeding if desired, though the fluffy seed heads are attractive in fall. Cut stems to ground level in late fall or early spring. The plant’s spreading habit means it may need management to prevent it from overwhelming other species in mixed plantings. Division can be done in early spring, but the plant’s deep roots make this challenging. Allow natural die-back in winter as the dried stems provide winter interest and wildlife habitat.

Landscape Uses

Fireweed’s dramatic height and stunning flowers make it valuable in specific landscape applications:

- Wildflower meadows and prairie restorations as a tall accent plant

- Disturbed site rehabilitation for erosion control and ecological restoration

- Pollinator gardens as an important nectar source for butterflies and bees

- Natural areas where aggressive spreading is acceptable or desired

- Mountain and alpine gardens in appropriate climate zones

- Fire-prone landscapes as part of fire-adapted plant communities

- Cutting gardens for dramatic, long-lasting flower arrangements

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Fireweed is one of North America’s most ecologically important wildflowers, playing crucial roles in forest succession, pollinator support, and wildlife habitat creation. Its significance extends far beyond its ornamental value, making it a keystone species in many northern and montane ecosystems.

For Birds

Numerous bird species benefit from Fireweed’s abundant seeds, which are produced in enormous quantities and remain available through fall and winter. Finches, siskins, and redpolls are particularly fond of the seeds, while hummingbirds occasionally visit the flowers for nectar. The tall, sturdy stems provide perching sites for flycatchers and other insect-eating birds that hunt from elevated positions. In winter, the dried stems create structural diversity that supports various bird species in otherwise simplified post-disturbance landscapes.

For Mammals

Large herbivores including deer, elk, and moose browse Fireweed foliage, particularly the tender young shoots in spring. Bears consume both the leaves and flowers, and the plant can form an important food source in post-fire landscapes where other forage may be temporarily scarce. Small mammals like voles and mice eat the seeds and may cache them for winter use. The plant’s role in creating early successional habitat benefits many mammal species that depend on edge environments and open areas.

For Pollinators

Fireweed is absolutely critical for pollinator conservation across its range, producing massive amounts of high-quality nectar over an extended blooming period. The flowers are visited by over 40 species of butterflies, including monarchs, painted ladies, and numerous fritillaries and skippers. Bumblebees, honeybees, and many native bee species depend on Fireweed as a major nectar and pollen source, particularly in northern regions where fewer flowering plants are available. The sequential blooming pattern ensures nectar availability for months, making it especially valuable for late-season pollinators.

Ecosystem Role

As a pioneer species, Fireweed plays a fundamental role in forest succession and ecosystem recovery following disturbances. Its deep roots help stabilize soil and prevent erosion, while its rapid growth provides quick ground cover in disturbed areas. The plant’s ability to fix nitrogen (through root associations with certain bacteria) helps improve soil conditions for subsequent plant communities. Fireweed’s dominance in early post-fire communities creates critical habitat for numerous species adapted to early successional environments, bridging the gap between disturbance and forest regeneration.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Fireweed has a rich history of human use across its extensive native range, serving Indigenous peoples and later European settlers as both food and medicine. The plant’s abundance and nutritional value made it an important resource, while its association with fire gave it spiritual and practical significance in many cultures.

Indigenous peoples throughout North America utilized Fireweed extensively. The young leaves and shoots were harvested in spring and eaten fresh or cooked as greens, providing important vitamins and minerals after long winters. Many tribes, including the Inuit, Athabascan, and various Pacific Northwest nations, processed the inner pith of young stems as a vegetable or dried it for winter storage. The flowers were used to make herbal teas, while some groups collected the abundant pollen as a protein-rich food supplement.

Medicinally, Native Americans used Fireweed to treat a wide variety of ailments. The leaves were commonly brewed into teas for digestive problems, respiratory issues, and women’s health concerns. Poultices made from the leaves were applied to wounds, burns, and skin irritations, taking advantage of the plant’s anti-inflammatory properties. Some tribes used Fireweed preparations to treat prostate problems and urinary tract issues, applications that have found support in modern herbal medicine.

European settlers quickly adopted many Indigenous uses for Fireweed, and the plant became known as “willowherb” in folk medicine traditions. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Fireweed tea was a popular beverage, particularly in Russia where it was called “Ivan Chai” and became a significant commercial product exported throughout Europe. The leaves were fermented and processed similarly to black tea, creating a caffeine-free alternative that was prized for its pleasant flavor and supposed health benefits.

During World War II, Fireweed gained symbolic significance in Britain when it rapidly colonized bomb sites in London and other cities, earning it the nickname “London Rocket.” The plant’s ability to quickly beautify devastated landscapes made it a powerful symbol of resilience and renewal during the war years. This association with recovery and regeneration continues to resonate in contemporary culture, where Fireweed is often used in restoration projects and as a symbol of ecological healing.

In modern times, Fireweed continues to be used in herbal medicine, particularly for prostate health and digestive issues, though its use should always be supervised by qualified practitioners. The plant has also found new applications in sustainable agriculture and ecological restoration, where its nitrogen-fixing ability and rapid establishment make it valuable for rehabilitating degraded lands and supporting pollinator populations in agricultural landscapes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it called Fireweed?

Fireweed gets its name from its tendency to rapidly colonize areas that have been burned by wildfire. It’s often one of the first plants to appear after a fire, sometimes creating spectacular displays across entire burned landscapes. The plant actually thrives in the mineral-rich soils and reduced competition found in post-fire environments.

Is Fireweed aggressive in gardens?

Yes, Fireweed can be quite aggressive, spreading by both seeds and rhizomes. In favorable conditions, it may quickly dominate an area and crowd out other plants. It’s best suited to naturalistic settings, wildflower meadows, or areas where its spreading habit is desired rather than formal garden beds with mixed plantings.

Can I eat Fireweed?

Yes, many parts of Fireweed are edible and have been used as food by Indigenous peoples for centuries. Young leaves and shoots can be eaten raw or cooked like spinach, though they become bitter as they age. The flowers can be used to make tea or added to salads. However, always properly identify the plant and harvest from clean areas away from roads or polluted sites.

Why aren’t my Fireweed flowers white if it’s called “White Fireweed”?

The reference to “White Fireweed” in some plant lists appears to be either a regional naming variation or possible confusion with other species. True Fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium) typically has pink to magenta flowers, though rare white-flowered forms do exist. The plant is much more commonly known simply as “Fireweed” or “Rosebay Willowherb.”

How can I prevent Fireweed from taking over my garden?

Preventing Fireweed from spreading requires vigilant management. Deadhead flowers before they set seed to prevent wind dispersal, and remove any rhizome shoots that appear outside desired areas. Installing root barriers can help contain the spreading rhizomes. Regular mowing or cutting will eventually weaken established colonies, though complete elimination can take several seasons of persistent effort.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Fireweed?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota