Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)

Cephalanthus occidentalis, commonly known as Buttonbush, Common Buttonbush, or Honey-balls, is one of the most ecologically productive native shrubs of the eastern and central United States. A member of the Rubiaceae (Madder) family, this distinctive wetland shrub is instantly recognizable by its extraordinary globular white flower heads — perfectly spherical clusters of small tubular florets that emerge in summer like botanical fireworks and are irresistible to hummingbirds, butterflies, and native bees alike. The common name refers perfectly to the flower heads, which resemble a collection of tiny buttons arranged in a ball.

Growing naturally along pond margins, stream banks, lake shores, and in swamps and wet lowlands throughout most of North America, Buttonbush thrives in conditions that challenge most other shrubs — standing water, periodic flooding, and heavy clay soils. Its tolerance of wet feet makes it invaluable for rain gardens, bioswales, and riparian restoration projects. Despite its love of wet conditions, established plants show surprising adaptability and can persist through temporary drought once their root systems are established in moist ground.

Buttonbush is more than a beautiful plant — it is an ecological powerhouse. Its fragrant flowers produce abundant nectar that supports pollinators through the heat of summer. Its seeds are a critical food source for waterfowl, especially wood ducks. Its dense, multi-stemmed structure provides excellent nesting habitat and cover for songbirds, while its submerged stems and roots create refuge habitat for fish and aquatic invertebrates. For anyone gardening near water or managing a wet site, Buttonbush is arguably the single most wildlife-valuable native shrub available.

Identification

Buttonbush is a deciduous shrub reaching 6 to 12 feet tall (occasionally taller in ideal conditions), with a broad, rounded, multi-stemmed form. The shrub typically grows wider than tall, creating a dense thicket that provides excellent wildlife cover. Young stems are green, aging to gray-brown with a slightly rough texture. The plant is most easily identified by its unique spherical flower heads, which are present for much of summer and are unlike any other native shrub in North America.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, opposite or in whorls of three, and elliptic to ovate in shape — 3 to 6 inches (7–15 cm) long and 1½ to 3 inches (4–8 cm) wide. They have smooth margins, a prominent midrib, and a glossy, dark green upper surface that contrasts with the paler underside. Leaves emerge late in spring — Buttonbush is one of the last shrubs to leaf out — and turn yellow before dropping in fall. This late emergence is a useful identification clue in spring.

Flowers

The flowers are Buttonbush’s most striking feature: tiny, tubular, white to cream-colored florets packed into perfectly spherical heads ¾ to 1¼ inches (2–3 cm) in diameter. Each floret has a long, protruding style that gives the globe a bristly, pincushion-like texture. Flowers are delightfully fragrant and bloom from June through September, with peak blooming in July–August. The spherical heads are borne on long stalks at the branch tips, making them highly visible and accessible to pollinators. Multiple heads may appear at each node, creating an abundant floral display throughout summer.

Fruit & Seeds

After flowering, the spherical heads transform into persistent, button-like clusters of reddish-brown nutlets — small, corky, angular seeds that remain on the plant well into winter. These nutlets are a critical food source for waterfowl (especially Wood Ducks and mallards) as well as shorebirds and songbirds. The persistent seed heads add winter interest to the landscape and provide valuable late-season food for wildlife when other food sources are depleted.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Cephalanthus occidentalis |

| Family | Rubiaceae (Madder) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 6–12 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | High (tolerates standing water and flooding) |

| Bloom Time | June – September |

| Flower Color | White to cream (spherical globes) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 5–10 |

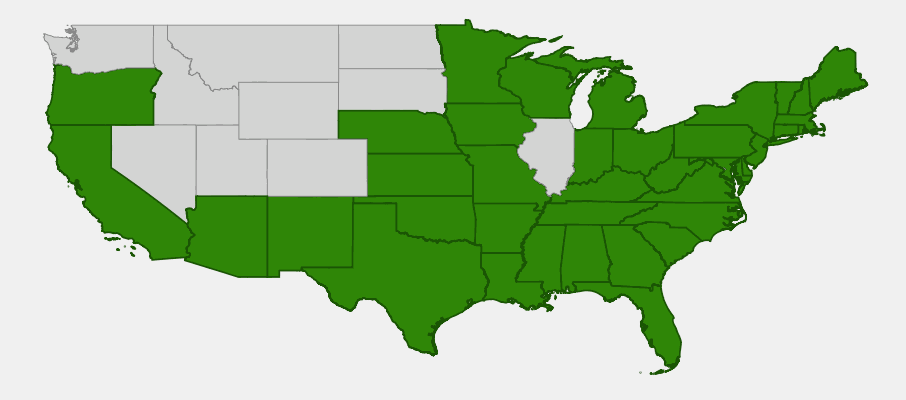

Native Range

Buttonbush is one of North America’s most widely distributed native shrubs, native from Maine and Ontario south to Florida, and west to California, Nebraska, and Texas. It occurs across most of the eastern United States, the Gulf Coast states, and extends into the Southwest and Pacific Coast regions wherever permanent water sources exist. It is one of the few native shrubs equally at home in the cool, forested wetlands of New England and the subtropical bayous of Louisiana and Florida.

Throughout its range, Buttonbush is strongly associated with wet habitats: the margins of ponds, lakes, rivers, and streams; seasonally flooded bottomlands; shrub swamps; wet prairies; and tidal freshwater marshes. It is a classic indicator species of high-quality wetland environments and is frequently encountered in the company of willows (Salix spp.), alders (Alnus spp.), Red Maple (Acer rubrum), and Swamp Rose (Rosa palustris). In the mid-Atlantic and New England regions, Buttonbush often forms dense thickets along pond edges and slow-moving streams.

Buttonbush grows from sea level to approximately 3,000 feet elevation throughout its range. In the northeastern United States — including New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey — it is a native component of beaver wetlands, river floodplains, and lake margins, where its tolerance of periodic inundation gives it a competitive advantage over most other shrubs. Its wide natural range reflects its tolerance of a broad range of climates, from boreal-edge conditions in the north to subtropical conditions in the south.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Buttonbush: New York, Pennsylvania & New Jersey

Growing & Care Guide

Buttonbush is an outstanding and underused native shrub for wet gardens, rain gardens, and naturalized wet areas. Its primary requirement is consistent moisture — given adequate water, it is a forgiving and robust plant that grows quickly and requires little maintenance once established.

Light

Buttonbush performs best in full sun to part shade. In full sun, it blooms most abundantly and develops its most compact form. It tolerates significant shade but may produce fewer flowers and grow more open and leggy under heavy tree canopy. Morning sun with afternoon shade is an excellent compromise, especially in warmer climates where afternoon heat can stress even wet-site plants.

Soil & Water

Unlike most shrubs, Buttonbush actually thrives in waterlogged soils and can tolerate prolonged flooding of 1–3 feet during the growing season. It is ideal for the edges of ponds, streams, and rain gardens where standing water is common. It grows in a variety of soil textures — clay, loam, sandy — as long as adequate moisture is present. For garden settings, a soil pH of 5.5–7.5 is suitable, and the plant tolerates a wide range of fertility levels. Established plants are also surprisingly drought-tolerant once the root system is deep and well-established in moist subsoil.

Planting Tips

Plant Buttonbush in spring or fall. Container-grown plants establish readily. Choose the wettest area of your property — the low spots that stay soggy, the margins of rain gardens, the edge of a pond or stream. Space plants 4–6 feet apart for a dense thicket, or 8–10 feet apart as specimens. Mulch well to retain moisture during establishment. Buttonbush transplants easily and grows quickly — expect 1–2 feet of growth per year once established.

Pruning & Maintenance

Buttonbush benefits from occasional rejuvenation pruning to keep it vigorous and shapely. If plants become overgrown, cut them back hard in late winter or early spring — they will resprout vigorously. For routine maintenance, remove dead or crossing branches and tip-prune to encourage branching. Avoid pruning after June, as this removes developing flower buds. Buttonbush is largely pest- and disease-resistant; it has very few serious problems in the landscape when properly sited.

Landscape Uses

Buttonbush excels in a variety of challenging wet-site applications:

- Rain gardens & bioswales — tolerates the wet-dry cycles typical of stormwater features

- Pond and stream margins — perfect for stabilizing banks and adding ecological value

- Wetland restoration — a keystone species for created and restored wetlands

- Hummingbird gardens — the fragrant, nectar-rich flowers are magnets for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds

- Butterfly gardens — draws swallowtails, fritillaries, and many other species

- Duck-friendly plantings — the persistent seed heads are beloved by waterfowl

- Native hedgerow — creates dense wildlife cover along wet site edges

- Erosion control on stream banks and pond margins

Toxicity Note

All parts of Buttonbush contain cephalanthin, a glycoside that is toxic to humans, horses, and livestock if consumed in quantity. Keep children and animals from ingesting any plant parts. However, the plant is perfectly safe in the landscape and has an excellent track record as a garden plant when not eaten.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Buttonbush is justly celebrated as one of the most wildlife-valuable native shrubs of the eastern United States. Few plants provide such breadth and depth of ecological services across so many different groups of animals.

For Birds

Buttonbush is exceptional for birds on multiple levels. Its persistent, button-like seed heads are a preferred food source for Wood Ducks, Mallards, Teal, and other waterfowl, as well as shorebirds and many songbirds. Studies have found Wood Ducks consuming Buttonbush seeds more than almost any other wetland plant. Prothonotary Warblers and other marsh-edge songbirds nest in and around Buttonbush thickets. The dense structure provides excellent nesting sites and protective cover during migration. In summer, the flowers attract the insects that insectivorous birds depend on for feeding nestlings.

For Mammals

Beaver relish Buttonbush bark and use the woody stems in dam and lodge construction — a sign of the plant’s importance in beaver-created wetland ecosystems. White-tailed Deer and rabbits browse the young growth, though the toxic glycosides in mature leaves make it somewhat deer-resistant when older. Muskrats consume the rootstock. The dense thickets provide essential cover for many small mammals in wetland habitats.

For Pollinators

The summer-blooming spherical flower heads are a spectacular nectar source during a period when many other flowering plants have finished blooming. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are frequent visitors, probing the tubular florets for nectar. Eastern Tiger Swallowtails, Spicebush Swallowtails, Great Spangled Fritillaries, Monarchs, and many other butterfly species feed at the flowers. Native bees — including bumble bees, leafcutter bees, and sweat bees — are constant visitors. Buttonbush has been documented supporting more than 18 species of native bees, and the flowers produce abundant pollen and nectar throughout the long summer bloom period.

Ecosystem Role

In wetland ecosystems, Buttonbush plays a structural role that goes far beyond its direct food value. Its submerged stems and root systems create complex physical habitat that supports aquatic invertebrates, small fish, frogs, salamanders, and turtles. As a pioneer species capable of establishing in newly created or restored wetlands, it initiates the successional development of wetland plant communities. Its dense above-water structure provides thermal cover and reduces wind at the water surface, moderating temperature extremes that can stress aquatic life. Buttonbush is now widely used in constructed wetland systems for water quality improvement, as its roots help filter nutrients and stabilize sediment.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Indigenous peoples of North America used Buttonbush extensively as a medicinal plant. The bark was used by numerous tribes — including the Iroquois, Cherokee, Choctaw, and others — to treat a wide variety of conditions. Decoctions of the bark were used to relieve toothache, reduce fever, treat malaria-like symptoms, address kidney problems, and as a general tonic. The Cherokee used bark tea to treat kidney disease and as an emetic. The Choctaw used it to treat eye conditions. The Potawatomi made a bark infusion to treat venereal disease.

The toxicity of cephalanthin — the plant’s active glycoside — was well known to Indigenous peoples, who used careful preparation methods to safely harness its medicinal properties. Early American settlers adopted many of these uses, and Buttonbush appeared in early American pharmacopeias as a treatment for intermittent fever (likely malaria), rheumatism, and skin conditions. The genus name Cephalanthus derives from the Greek words for “head” (kephalē) and “flower” (anthos), a fitting description of the plant’s most striking feature.

Beyond its medicinal history, Buttonbush has long been valued for its exceptional honey production. Bees work the fragrant flower heads intensively throughout summer, producing honey described as having a strong, distinctive, somewhat bitter flavor. The wood of Buttonbush is hard and fine-grained but the stems are generally too small for significant commercial use. Today, Buttonbush is increasingly recognized as a premier rain garden and wetland restoration plant, and is grown by native plant nurseries throughout its range. Its combination of spectacular summer flowers, exceptional wildlife value, and ability to thrive in the wettest garden sites makes it an increasingly popular landscaping choice for environmentally-minded gardeners.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does Buttonbush grow in standing water?

Yes — Buttonbush is one of the few native shrubs that can tolerate prolonged flooding, standing in 1–3 feet of water during the growing season. It naturally grows along pond margins and in swamps. For home gardens, it thrives at the edge of ponds, in rain gardens that hold water, and along stream banks.

Is Buttonbush poisonous?

All parts of Buttonbush contain cephalanthin, a glycoside that is toxic to humans, horses, and livestock if eaten in significant quantities. Symptoms of poisoning include nausea, vomiting, and paralysis. As a landscape plant, it is safe — the danger exists only if plant material is consumed. Keep children and animals from eating any part of the plant.

Does Buttonbush attract hummingbirds?

Yes — Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are frequent and enthusiastic visitors to Buttonbush flowers, probing the tubular florets for nectar. The fragrant, spherical flower clusters bloom through the heat of summer and are particularly attractive to hummingbirds during their peak summer activity. Planting Buttonbush near a water feature creates an especially appealing habitat scene for hummingbirds.

How fast does Buttonbush grow?

Buttonbush grows at a moderate to fast rate — typically 1–2 feet per year under favorable conditions. In full sun with consistently moist soil, growth is fastest. Even in part shade or temporarily drier conditions, it establishes reliably and begins producing flowers by its second or third year after planting.

Will deer eat Buttonbush?

Deer may browse young shoots of Buttonbush, particularly in early spring when other food sources are limited, but the plant’s natural toxins make mature foliage somewhat unpalatable. Overall, Buttonbush is considered moderately deer-resistant, and in most landscapes the plants quickly outgrow any deer damage. Fencing young plants may be advisable in areas with heavy deer pressure.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Buttonbush?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: New York · Pennsylvania