Black Oak (Quercus velutina)

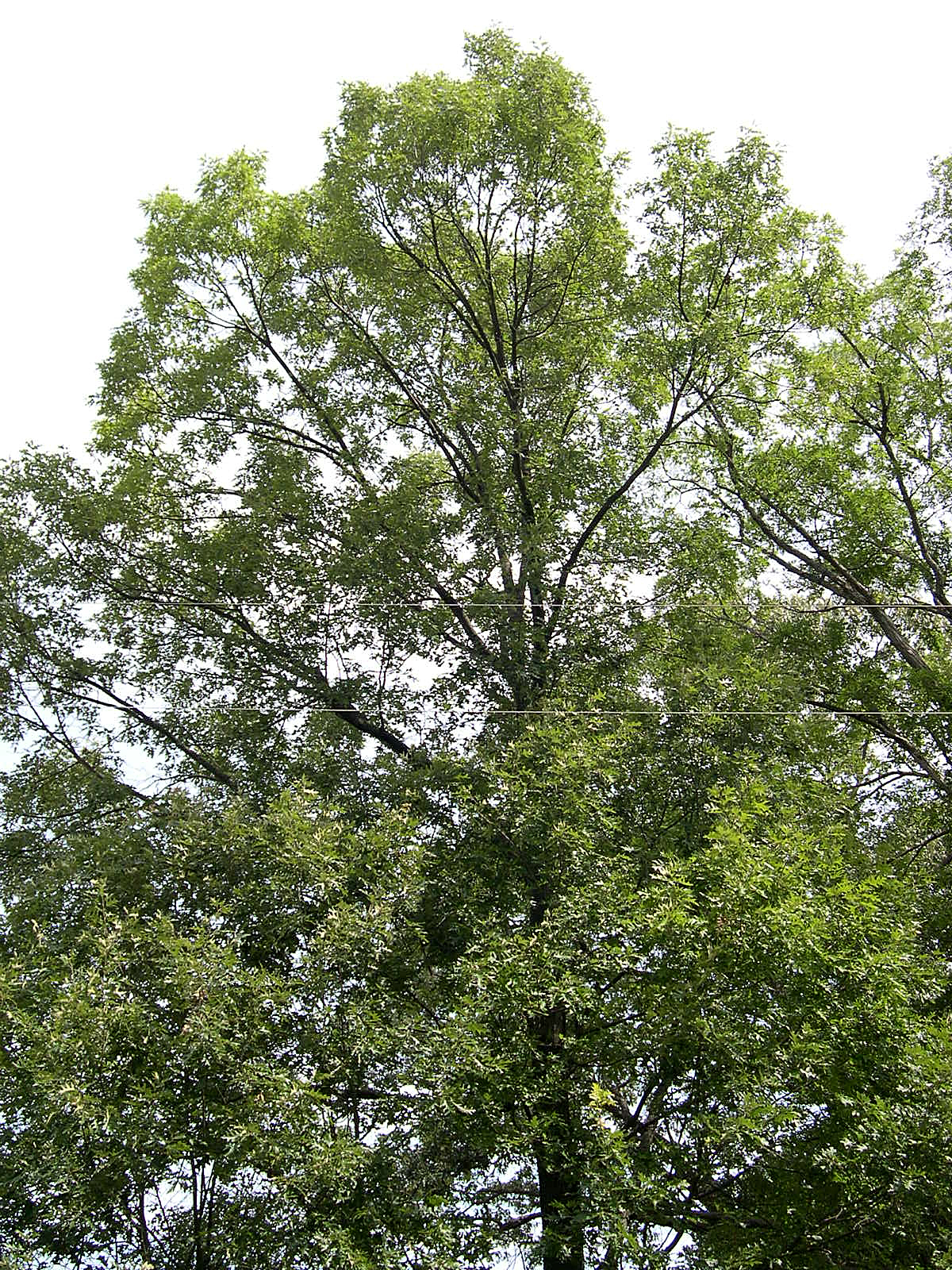

Quercus velutina, commonly known as Black Oak, is one of the most ecologically significant and widely distributed native oaks in eastern North America. A member of the red oak group (section Lobatae), this large, long-lived deciduous tree has fueled countless forest ecosystems for millennia — its massive acorn crops feeding bears, deer, wild turkeys, wood ducks, and dozens of songbirds. The name “Black Oak” refers to the very dark, nearly black outer bark of mature trees, a distinctive feature that sets it apart from other eastern oaks at a glance.

Across its broad range — from New England and southern Canada south to northern Florida, and west to Nebraska — Black Oak is a reliable component of upland mixed hardwood forests, dry ridges, and sandy-soil savannahs. It thrives where other oaks struggle, tolerating poor, rocky, and acidic soils while producing one of the most nutritious and abundant acorn crops in eastern North America. Mature trees can reach 50 to 80 feet in height with a broad, open crown that spreads 40 to 60 feet wide, creating enormous habitat value wherever they grow.

Though often overshadowed by White Oak or Northern Red Oak in commercial and horticultural contexts, Black Oak is an irreplaceable component of eastern upland forests. Its deep taproot anchors eroding slopes, its leaf litter acidifies and enriches the soil beneath, and its acorns — produced in abundance every 2 to 3 years — feed a food web that includes over 150 animal species. For naturalistic landscapes, wildlife gardens, or reforestation projects, Black Oak is one of the most powerful ecological investments you can make.

Identification

Black Oak is a large deciduous tree typically reaching 50 to 80 feet (15–24 m) tall with a trunk 1 to 3 feet in diameter. The crown is broad and irregular, often wider than the tree is tall in open-grown specimens. One of the most reliable identification features is the intensely yellow inner bark — scratch through the dark outer bark and you’ll find brilliant yellow tissue beneath, the result of the pigment quercitron, historically used as a yellow dye.

Bark

The bark of Black Oak is its most recognizable feature at a distance. On young trees it is smooth and grayish-brown; on mature trees it becomes very dark — almost black — and breaks into blocky, rough ridges and furrows. This very dark, deeply furrowed bark is what gives the species its common name. The inner bark is notably yellow-orange, visible when the outer bark is cut or scratched. This yellow inner bark was used commercially in the 1800s to extract quercitron, a natural yellow-orange dye used extensively in the textile industry.

Leaves

The leaves are 5 to 9 inches (13–23 cm) long, deeply lobed with 7 to 9 lobes ending in sharply pointed bristle-tipped teeth — a characteristic of all red oaks. The lobes are separated by deep sinuses that reach more than halfway to the midrib. The upper surface is shiny dark green and glossy; the underside is paler and may have small tufts of rusty-brown hairs in the vein axils. Leaves turn a rich red to rusty-brown in autumn before dropping. Unlike White Oak’s rounded leaf lobes, Black Oak’s lobes always end in sharp, pointed bristle-tips.

Flowers & Acorns

Like all oaks, Black Oak produces separate male and female flowers on the same tree. Male flowers hang in long, slender catkins 2 to 4 inches long in April and May as the leaves emerge. Female flowers are tiny and inconspicuous, occurring singly or in clusters. The acorns mature over two growing seasons — a key red oak group characteristic. Mature acorns are about ½ to ¾ inch (12–18 mm) in diameter, round to oval, and about half-enclosed in a deep, fringed cup. The nut surface is dull brown, often with a dark cap line. Acorns are produced abundantly in mast years, typically every 2 to 3 years, with smaller crops in between.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Quercus velutina |

| Family | Fagaceae (Beech) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 50–60 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Low (Drought Tolerant) |

| Bloom Time | April – May |

| Flower Color | Yellow-green (catkins) |

| Fall Color | Red to rusty-brown |

| Fruit / Seed | Acorn (matures in 2 years) |

| Soil Tolerance | Dry, sandy, rocky, acidic soils |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

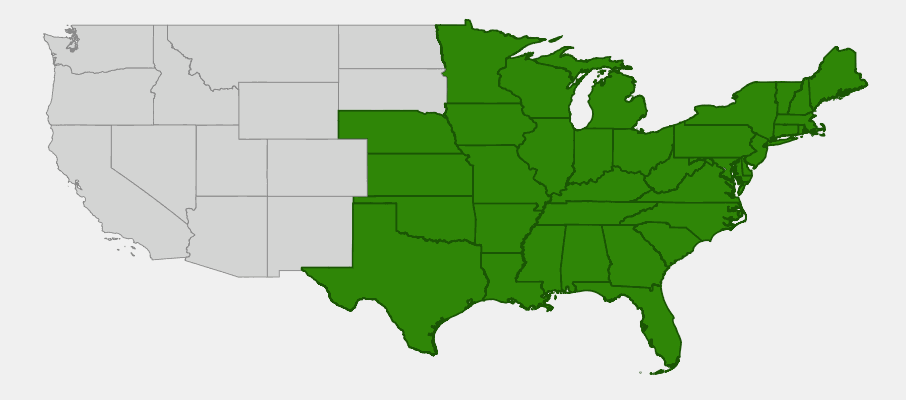

Native Range

Black Oak has one of the broadest natural ranges of any eastern North American oak, extending from southern Maine and southern Ontario west to Nebraska and Kansas, and south through the entire eastern United States to northern Florida and eastern Texas. It is especially abundant in the interior eastern states — the Midwest, Ohio Valley, and mid-Atlantic region — where it forms a major component of upland mixed-oak forests.

Within its range, Black Oak occupies dry to moderately dry upland sites: ridgelines, south- and west-facing slopes, sandy plains, and outwash deposits where soils are thin and acidic. It is a characteristic species of the oak-hickory forest region and reaches its greatest abundance on well-drained sandy soils of the Atlantic Coastal Plain and interior uplands. It frequently grows alongside Scarlet Oak (Quercus coccinea), Chestnut Oak (Quercus montana), and various hickories.

The species is notably well-adapted to fire — it has thick, insulating bark that protects the cambium, and sprouts vigorously from the base and root collar after top-kill by fire. Many of the oak savannahs and open oak woodlands historically maintained by Indigenous burning in the Midwest depended on Black Oak’s fire tolerance. Without periodic disturbance, Black Oak is gradually replaced by more shade-tolerant species in closed-canopy forests.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Black Oak: New York, Pennsylvania & New Jersey

Growing & Care Guide

Black Oak is a tough, adaptable tree well-suited to challenging planting sites. Like all oaks, it establishes slowly but grows steadily once its deep taproot is established — typically 1 to 2 feet per year under good conditions. Patience with young oaks is rewarded with a tree that will outlive any other landscape planting.

Light

Black Oak grows best in part shade to full shade conditions in its woodland habitat, though it tolerates full sun well in open landscape settings. In open sites with full sun it develops a broad, expansive crown. Young seedlings establish best beneath light canopy shade, which mimics natural conditions. Avoid deep, permanent shade — while young trees can tolerate it temporarily, mature Black Oaks thrive with good light access.

Soil & Water

Black Oak is highly drought tolerant, making it ideal for dry, thin soils where most trees struggle. It naturally colonizes sandy, rocky, and acidic soils with low organic matter and excellent drainage. While it can tolerate moderately moist soils, it absolutely will not tolerate waterlogged or compacted soils with poor drainage — these conditions can cause root rot and eventual decline. Once established (3–5 years), Black Oak requires no supplemental irrigation in most eastern climates. Soil pH should ideally be below 7.0; neutral to acidic soils are preferred.

Planting Tips

Plant in fall (September–November) for best establishment. Acorns can be direct-sown in fall. Container-grown stock should be planted carefully to avoid disturbing the taproot. Avoid amending the planting hole with organic matter — Black Oak is adapted to lean soils, and rich planting conditions can promote excessive top growth at the expense of root development. Mulch with 3 inches of wood chips out to the drip line, keeping mulch away from the trunk.

Pruning & Maintenance

Remove dead or damaged branches in late winter. Prune for structure during the first 10–15 years to establish a strong scaffold of primary branches. Avoid heavy pruning of mature trees, as large wounds are slow to seal in oaks. Do not prune during April through June (the prime period for oak wilt transmission by beetles), especially in states where oak wilt is a concern. Black Oak is generally pest- and disease-resistant, though it is susceptible to oak wilt in the Midwest.

Landscape Uses

- Upland and dry-slope naturalization on ridges and well-drained hillsides

- Wildlife gardens — one of the highest wildlife value trees in the East

- Savannah restoration — a keystone species of Midwestern oak savannahs

- Large shade tree for parks, estates, and open lawns

- Reforestation on dry, marginal lands recovering from disturbance

- Street tree in climates with reliable summer rainfall

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Black Oak is one of the most ecologically productive native trees in eastern North America, rivaling White Oak in its importance to wildlife food webs. Its acorns, leaves, bark, and canopy structure support hundreds of species across multiple trophic levels.

For Birds

The acorns of Black Oak are critically important to many bird species. Wild Turkeys, Wood Ducks, Blue Jays, Woodpeckers, Tufted Titmice, Nuthatches, and dozens of other species consume Black Oak acorns, often caching them for winter use. Jays in particular are essential distributors of Black Oak seeds, carrying acorns hundreds of meters from parent trees and burying them in caches — many of which sprout into new trees. The dense canopy provides nesting habitat for a large number of songbirds, raptors, and cavity-nesting species such as Red-headed Woodpeckers.

For Mammals

White-tailed Deer, Black Bears, Gray Squirrels, Fox Squirrels, Raccoons, and Wild Turkeys are among the most important mammalian consumers of Black Oak acorns. Deer browse the foliage of young trees, and squirrels are major seed-caching agents. Gray Squirrels have been shown to prefer red oak group acorns (including Black Oak) for burial — because the high tannin content delays germination, the cached acorns remain viable through winter. A single Black Oak in a mast year can produce over 20,000 acorns, providing a significant food subsidy for the surrounding wildlife community.

For Pollinators

Though not a showy pollinator plant, Black Oak catkins produce abundant pollen in spring that supports native bees, particularly native sweat bees and mining bees, as well as many beetles. The tree also hosts over 500 species of Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) caterpillars — a number rivaled only by White Oak and Willow in eastern North America — making it one of the most important larval host plants for forest food webs. These caterpillars in turn are the primary food source for songbirds raising nestlings.

Ecosystem Role

Black Oak is a keystone species in dry upland forests and oak savannahs throughout eastern North America. Its acorns form the foundation of forest food webs — the “acorn connection” links primary producers to top predators through a chain of consumers from weevils to squirrels to hawks. The tree’s deep taproot mines subsoil nutrients and its acid leaf litter drives the chemistry of forest floor soils. Fire-adapted and deep-rooted, Black Oak is a major driver of forest resilience and recovery after disturbance.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Black Oak has a long history of use by Indigenous peoples across eastern North America. The acorns, while highly tannic when raw, were processed to remove tannins through repeated washing and boiling — producing a starchy flour used to make breads, porridges, and soups. Various nations, including Cherokee, Iroquois, and Algonquian peoples, used Black Oak acorn meal as a staple food and developed detailed knowledge of how to process each oak species’ acorns to reduce bitterness.

The distinctive yellow inner bark of Black Oak was the source of a commercial dye called quercitron — derived from “Quercus” and “citron” for its lemon-yellow color. From the late 18th century through the early 20th century, quercitron was one of the most important commercial dyestuffs in the American and European textile industries. It was used to produce yellow, orange, and olive dyes on wool and silk, and America exported large quantities of quercitron to European dyers. The bark was harvested commercially, contributing to the decline of large Black Oaks in some regions.

In traditional herbal medicine, Black Oak bark was used as an astringent and antiseptic by both Indigenous peoples and early European settlers. Tannin-rich decoctions of the bark were applied to wounds, burns, and skin irritations. The wood of Black Oak is heavy, hard, and strong — commercially important as “red oak” lumber, used for flooring, furniture, cabinetry, railroad ties, and fuel. Though not as rot-resistant as White Oak, it was widely used for construction in the 19th and early 20th centuries throughout the eastern United States.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between Black Oak and Red Oak?

Black Oak (Quercus velutina) and Northern Red Oak (Quercus rubra) are closely related and sometimes confused. The most reliable differences: Black Oak’s bark is darker and more deeply furrowed; its inner bark is yellow (Red Oak’s is pinkish); its acorn cup covers roughly half the nut (Red Oak’s cup is shallower, covering about ¼); and its leaves often have deeper sinuses. The two species hybridize naturally where their ranges overlap.

How fast does Black Oak grow?

Black Oak is considered a moderate-growth tree, typically adding 1 to 2 feet per year once established. Growth is slowest in the first 3 to 5 years while the deep taproot is developing. After establishment, trees can grow 2+ feet per year in good conditions. Open-grown trees develop broader crowns and often grow faster than woodland-grown trees competing for light.

When does Black Oak produce acorns?

Black Oak acorns require two growing seasons to mature — a characteristic of all red oak group oaks. Acorns that form in spring of Year 1 mature in fall of Year 2. Most trees produce heavy acorn crops every 2 to 3 years (mast years) with lighter crops in between. Trees generally begin producing acorns at 20 to 25 years of age, with peak production between 40 and 75 years.

Is Black Oak good for wildlife?

Exceptionally so. Black Oak supports over 150 animal species through its acorns, leaf litter invertebrates, and canopy habitat. It hosts over 500 species of moth and butterfly caterpillars — a critical link in forest food webs that sustains songbird populations during the breeding season. Few landscape trees rival Black Oak’s ecological value per square foot of canopy.

Can Black Oak grow in clay soil?

Black Oak prefers well-drained to dry soils and is not well-suited to heavy clay with poor drainage. It will tolerate moderately clay soils if drainage is adequate, but waterlogged conditions cause root rot. If your site has poorly drained clay, consider Swamp Oak (Quercus bicolor) or Pin Oak (Quercus palustris) instead. For sites with dry to moderately drained clay, Black Oak may establish with proper site preparation.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Black Oak?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: New York · Pennsylvania