Golden Currant (Ribes aureum)

Ribes aureum, commonly known as Golden Currant, Clove Currant, or Buffalo Currant, is a vigorous, fragrant native deciduous shrub of central and western North America. A member of the Grossulariaceae (gooseberry) family, this remarkably beautiful and ecologically valuable plant is famous for its cascades of bright yellow, spice-scented flowers in early spring — among the showiest native flowers of any shrub in the Intermountain West. The blooms carry a rich, spicy fragrance often compared to cloves or vanilla, giving the plant its alternative common name “Clove Currant.”

Golden Currant grows 4 to 6 feet tall and equally wide, forming a densely branched, fountaining shrub with handsome three-lobed leaves that turn vibrant shades of orange and red in fall. In spring, before or alongside the emerging leaves, it produces drooping clusters of 5–15 brilliant yellow flowers. By late summer, the plant produces abundant small berries that ripen through red to golden yellow to purple-black, providing exceptional fruit for both wildlife and humans. The berries are sweet and flavorful, used in jams, jellies, pies, and dried fruit preparations by Indigenous peoples and settlers alike.

One of the most adaptable of all native currants, Golden Currant tolerates a wide range of soils and moisture conditions, performing well in part shade to full sun. Its drought tolerance once established, combined with its exceptional ornamental and wildlife value, make it one of the most recommended native shrubs for Intermountain West landscapes, xeriscape gardens, wildlife plantings, and riparian restoration projects. It is notably spineless — unlike its close relative the Gooseberry — making it far easier to work around in the garden.

Identification

Golden Currant is an upright to arching, multi-stemmed deciduous shrub reaching 4–6 feet tall and wide. It lacks thorns (unlike gooseberries, Ribes subgenus Grossularia), which distinguishes it from prickly currant relatives. Young stems are smooth and reddish; older stems become gray-brown and somewhat shreddy. The plant produces no thorns on any part.

Leaves

The leaves are alternate, simple, and distinctively three-lobed (resembling a maple leaf in miniature), ¾ to 2 inches wide. The lobes are blunt-toothed, and the leaf surface is smooth to slightly hairy. Leaves are bright green in spring and summer, turning brilliant orange, red, and purple in fall — one of the best fall color displays of any native Intermountain West shrub. The fall color alone makes Golden Currant worth planting as an ornamental.

Flowers & Fruit

The flowers are produced in pendulous racemes of 5–15 flowers, typically blooming April–May before or alongside the emerging leaves. Each flower is about ½ inch long, tubular to trumpet-shaped with five bright yellow petals fused at the base into a tube, and five reflexed yellow sepals extending backward. The flowers have a strong, sweet, spicy-clove fragrance that can be detected several yards away on warm spring days. The color and form make them extraordinary pollinator resources — particularly for early-emerging hummingbirds and native bees.

The fruit is a small berry (about ¼–⅜ inch diameter) that ripens through a spectacular color progression: initially green, then red, then golden-yellow to amber, and finally deep purple-black when fully ripe. Multiple colors of berries can appear on the same plant simultaneously, creating a striking display. The berries are sweet and juicy when ripe — among the best-tasting of any Ribes species. Birds begin consuming them when still red; ripe black berries are especially attractive to a wide variety of wildlife.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Ribes aureum |

| Family | Grossulariaceae (Gooseberry) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 4–6 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | April – May |

| Flower Color | Bright yellow (clove-scented) |

| Fruit | Berries ripening red to yellow to purple-black |

| Fall Color | Orange to red to purple |

| Deer Resistant | Moderately (browsed but not a preferred food) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–8 |

Native Range

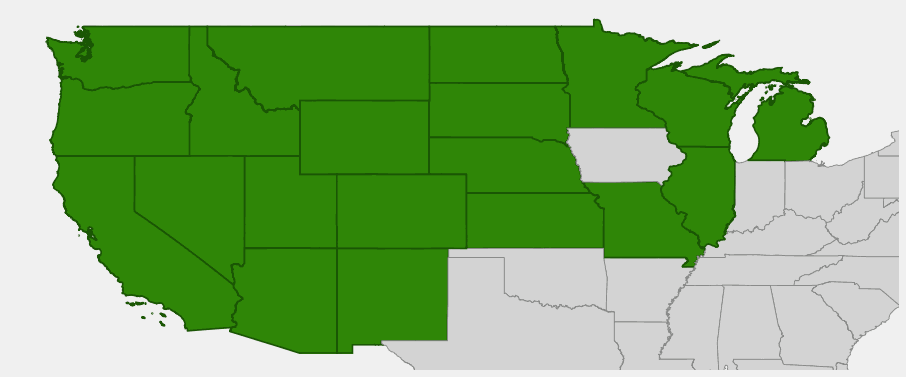

Golden Currant has one of the broadest native ranges of any Ribes species in North America, extending from the Pacific Coast states east across the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains to the upper Midwest. In the west, it is native from Washington and Oregon east through Idaho and Montana, south through Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, and Arizona, and across the Great Plains states from North Dakota south through Nebraska and Kansas. Isolated populations also occur in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, and Missouri.

Within the Intermountain West, Golden Currant grows along stream corridors, in canyon bottoms, on rocky slopes with some moisture, and along the margins of sagebrush communities where soil moisture is seasonally adequate. It is a characteristic species of riparian shrub communities at mid-elevations, often growing alongside willows, wild roses, and serviceberry. In the Great Plains, it grows along creeks and in draws where additional moisture accumulates in otherwise dry landscapes.

The species was collected by Meriwether Lewis near the mouth of the Marias River in Montana in 1806 during the Lewis and Clark Expedition, making it one of the first native western currants to be scientifically documented. Lewis noted the fragrance and edibility of the berries in his journals. Golden Currant later became popular in European horticulture, where a larger-fruited variety (Ribes aureum ‘Crandall’) was selected for garden cultivation and fruit production.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Golden Currant: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Golden Currant is one of the easiest and most rewarding native shrubs to grow in Intermountain West and Rocky Mountain gardens. Once established, it requires minimal care and rewards gardeners with a spectacular four-season display of fragrant flowers, colorful berries, and brilliant fall foliage.

Light

Golden Currant performs best in part shade to dappled light, though it tolerates full sun in cooler climates with adequate moisture. In the hot, dry Intermountain West, afternoon shade helps maintain vigor and berry production during summer. In cooler Pacific Northwest locations, full sun is acceptable and promotes the most abundant flowering. Avoid deep, dense shade, which dramatically reduces flowering and fruit set.

Soil & Water

One of Golden Currant’s great strengths is its soil adaptability. It grows in sandy, loamy, clay, or rocky soils and tolerates both slightly acidic and alkaline conditions — particularly useful in the often-alkaline soils of the Intermountain West. While it prefers moderate moisture and performs best with regular water during the growing season, established plants develop considerable drought tolerance. Deep, infrequent watering encourages deeper root development and better drought resistance than frequent shallow watering.

Planting Tips

Plant Golden Currant in fall or early spring. Container-grown plants establish quickly; bare-root stock is available from native plant nurseries. Space plants 4–5 feet apart for a dense wildlife hedge, or 6–8 feet apart for individual specimens with more room to spread. Golden Currant spreads by root suckers and can form thickets over time — remove suckers if a more contained habit is desired, or allow them to naturalize for a wildlife-friendly hedgerow effect.

Pruning & Maintenance

Golden Currant requires minimal pruning. Remove dead or crossing branches in late winter and prune out any old, woody stems at the base every few years to encourage vigorous new growth and maximum berry production — currants fruit best on 2- to 4-year-old wood. The shrub naturally renews itself over time. Little fertilizer is needed; a light application of compost in spring promotes lush growth in poor soils.

Landscape Uses

Golden Currant is exceptionally versatile in the native landscape:

- Wildlife habitat shrub — flowers feed early pollinators; berries attract birds and mammals

- Hummingbird garden — the yellow tubular flowers are excellent for Rufous and Calliope Hummingbirds on spring migration

- Native fruit garden — berries are among the best-tasting of any native currant

- Riparian restoration — excellent for streambank planting and riparian buffer projects

- Xeriscape planting — drought-tolerant once established, great for low-water gardens

- Hedgerow and screen — dense growth makes an effective garden border

- Fall foliage accent — vivid orange and red fall color rivals many ornamental shrubs

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Golden Currant is a keystone native shrub for wildlife across its broad range, providing exceptional resources across spring, summer, and fall.

For Pollinators

The early-blooming, richly fragrant yellow flowers of Golden Currant are among the most important spring nectar sources for a wide range of pollinators. Rufous Hummingbirds actively seek out currant flowers during their spring migration north, and the tubular flower shape is well-adapted for hummingbird foraging. Bumble bee queens — emerging from winter dormancy in search of early-season carbohydrates — are major visitors. Numerous native bee species, including mining bees, sweat bees, and mason bees, collect both nectar and pollen from the flowers. The bloom period (April–May) coincides with a critical window when many pollinators are building their colonies after winter.

For Birds

The berries are consumed by dozens of bird species including American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Gray Catbirds, Brown Thrashers, Hermit Thrushes, House Finches, Purple Finches, and many species of sparrows. The multi-stage ripening — with berries ranging from red to black on the plant simultaneously — extends the fruiting season and maximizes the period during which birds can forage. In late summer and fall, Golden Currant berries are a critical food source for migratory birds building fat reserves for long-distance travel.

For Mammals

Black Bears, coyotes, foxes, raccoons, and ground squirrels all eat Golden Currant berries. The fruit is one of the most eagerly consumed by bears, which can strip entire shrubs quickly when fruits are ripe. Deer browse the foliage moderately. The shrub’s dense structure provides cover for small mammals year-round, and its root system is nibbled by voles and pocket mice.

Ecosystem Role

Golden Currant is an important structural species in riparian and edge communities across the Intermountain West. Its early flowering provides resources at a critical time of year, while its dense foliage and fruit production support food webs across multiple trophic levels. As a nitrogen-fixer-associate (growing near nitrogen-fixing species like alders), it contributes to soil fertility in riparian zones. The plant also serves as a host for several Ribes-associated insects that are in turn important prey items for insectivorous birds.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Golden Currant berries were widely used as food by Indigenous peoples across its vast range. The Lakota, Crow, Arikara, Shoshone, Paiute, Ute, and many other nations harvested the sweet berries fresh in late summer and dried them for winter use. Dried currants were pressed into cakes or mixed with dried meat and rendered fat to make pemmican — one of the most energy-dense and shelf-stable traditional foods of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain peoples. The berries were also cooked with other foods to add sweetness and flavor. In many Native languages, the plant’s names reference its golden flowers or sweet berries.

Lewis and Clark collected Ribes aureum specimens during their 1806 return journey through Montana, and the plant was subsequently introduced to European horticulture, where it became a popular ornamental and fruit shrub. In 19th-century American homestead gardens, Golden Currant was widely planted by settlers who valued both its spring flowers and its edible berries. The cultivar ‘Crandall’ — selected for its larger, sweeter berries — became popular in fruit gardens and remains available today.

In modern use, Golden Currant berries make excellent jams, jellies, pies, and dried fruit. The berries can be substituted for black currants in most recipes. The fragrant flowers are edible and can be used as a garnish or infused into syrups and beverages. Golden Currant is increasingly used in native plant restoration projects across the West, where it provides rapid establishment, excellent erosion control, and immediate wildlife habitat value. Its broad adaptability to diverse soils and climates makes it one of the most valuable and versatile tools in the native plant restoration toolkit.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Golden Currant berries edible?

Yes — Golden Currant berries are among the best-tasting of any native currant, with a sweet, rich flavor similar to a mild black currant. They can be eaten fresh when fully ripe (purple-black stage), or used in jams, jellies, pies, syrups, and dried fruit preparations. Birds compete with humans for the ripe berries, so harvest promptly when they reach full ripeness.

Is Golden Currant drought tolerant?

Yes, once established (typically after the first or second growing season). Golden Currant develops deep roots that access subsoil moisture, making it more drought-tolerant than many native shrubs. It performs best with moderate water but can survive on natural rainfall in much of the Intermountain West after establishment. Water deeply but infrequently rather than with frequent shallow irrigation.

Will Golden Currant spread and become invasive in my garden?

Golden Currant spreads by root suckers and can form a thicket over time, but it is not invasive — it is a native species controlled by garden conditions. Simply remove suckers as they appear to maintain a single-shrub form, or allow them to naturalize into a wildlife hedgerow. It does not aggressively outcompete other plants.

When do Golden Currant berries ripen?

Berries begin to ripen in mid-to-late summer (July–August in most of the Intermountain West), with the color progression from green to red to yellow-amber to purple-black occurring over several weeks. Multiple colors of berries coexist on the plant simultaneously, extending the fruiting season. Fully ripe berries are dark purple-black and easily pull away from the stem.

What is the difference between Golden Currant and Buffalo Currant?

“Buffalo Currant” is an alternate common name for the same species, Ribes aureum, particularly used in the Great Plains states. The name reflects the plant’s association with the Great Plains ecosystem where bison (buffalo) once roamed. “Golden Currant” and “Clove Currant” are the most widely used common names across the plant’s range.