Big Tooth Maple (Acer grandidentatum)

Acer grandidentatum, commonly known as the Big Tooth Maple or Canyon Maple, is one of the most spectacular native trees of the Intermountain West. A close relative of the eastern Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum), this western counterpart lights up canyon walls and mountain slopes with brilliant red, orange, and gold foliage each autumn — earning it legendary status among fall color enthusiasts who know where to find it. Its large, deeply-lobed leaves — the source of its scientific name, meaning “large-toothed” — set it apart from other maples and make identification easy even from a distance.

Native to the canyons, rocky slopes, and mountain foothills of the southern Rocky Mountains and Intermountain West, Big Tooth Maple thrives in locations that would seem inhospitable to most trees: dry canyon walls, talus slopes, and gravelly streambanks at elevations from 4,500 to 8,000 feet. It is remarkably drought-adapted compared to its eastern relatives, making it an excellent choice for water-wise landscaping in the arid West while still delivering the four-season beauty that makes maples beloved. In spring, small yellow-green flowers emerge before the leaves; by summer, paired samaras (winged seeds) ripen; and in autumn, the show-stopping foliage transforms entire canyons into rivers of color.

For wildlife and ecological value, Big Tooth Maple punches far above its modest size. The seeds are important food for birds including grosbeaks and finches; the foliage and twigs are browsed by mule deer, elk, and pronghorn; and the dense canopy provides critical nesting cover in otherwise exposed canyon environments. Indigenous peoples of the Southwest and Great Basin have long used the wood, sap, and bark of this tree for food, tools, and medicine. Today, it is increasingly recognized as a premier native tree for xeriscape gardens, canyon restoration, and wildlife habitat in the Intermountain West.

Identification

Big Tooth Maple is a deciduous tree or large multi-stemmed shrub, typically reaching 15–30 feet in height with a spread of 15–25 feet. Trees growing in protected canyon bottoms with access to seepage water can occasionally reach 40 feet. The crown is broadly rounded to irregular, often more open and airy than the dense Sugar Maple. The species is easily recognizable by its large, palmate leaves and brilliant autumn color.

Bark

The bark of young Big Tooth Maple is smooth and gray-brown, becoming darker and developing shallow furrows and interlacing ridges on older trunks. The inner bark is reddish-brown. Twigs are slender, reddish to gray-brown, with small, paired, reddish buds. The bark texture is less deeply furrowed than eastern Sugar Maple and does not produce significant quantities of sweet sap — attempts to tap this western maple for syrup production yield disappointing results compared to its eastern cousin.

Leaves

The leaves are the defining feature of this species. Each leaf is 2–4 inches (5–10 cm) wide, palmately lobed with 3–5 deeply-cut lobes that have large, blunt teeth along the margins — hence “grandidentatum” (large-toothed). The upper surface is dark green and moderately shiny; the underside is paler and may have tufts of hair in the vein axils. The leaves turn brilliant red, orange, yellow, or burgundy in autumn — often multiple colors on the same tree — and persist on the branches for several weeks before dropping.

Flowers & Fruit

Small, yellowish-green flowers emerge in drooping clusters from the branch tips in early spring (March–May), typically just as the leaves are unfolding. The flowers are functionally unisexual on the same or different trees (the species is polygamo-dioecious). By summer, the distinctive paired samaras (winged seeds, or “helicopters”) ripen — each pair joined at the base with wings spreading at a nearly 180-degree angle. The samaras are about 1 inch long, and turn from green to tan as they mature, eventually twirling to the ground in late summer. The seeds are an important food source for birds and small mammals, particularly in the fall and winter.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Acer grandidentatum |

| Family | Sapindaceae (Soapberry / Maple) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree / Large Shrub |

| Mature Height | 30 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate |

| Bloom Time | March – May |

| Flower Color | Yellowish-green |

| Fall Color | Brilliant red, orange, gold, burgundy |

| Wildlife Value | Seeds (birds, mammals); foliage (deer, elk) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–8 |

Native Range

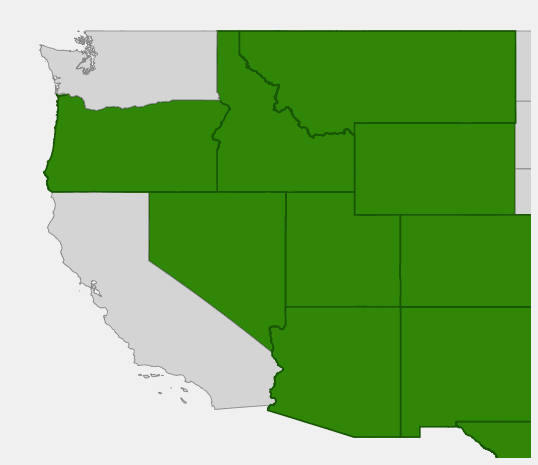

Big Tooth Maple is native to the southern Rocky Mountains and Intermountain West, where it is most commonly found in canyon environments at mid-elevations. Its range extends from southwestern Wyoming and western Colorado south through Utah, Nevada, and Arizona into New Mexico and Texas (including the Guadalupe Mountains), and west into southern Idaho and occasionally Oregon. Within this range, it tends to form dense thickets in protected canyon bottoms or appear as scattered individuals on rocky north-facing slopes where moisture lingers longer.

In Utah — perhaps the stronghold of the species — Big Tooth Maple turns entire canyon walls and mountain slopes into a riot of autumn color. Hobble Creek Canyon, Provo Canyon, Spanish Fork Canyon, and the slopes of the Wasatch Range are famous for their Big Tooth Maple displays, which rival anything New England has to offer. The species forms pure stands in favorable locations and mixes with Gambel Oak (Quercus gambelii), Boxelder (Acer negundo), and various willows and cottonwoods at lower elevations.

Big Tooth Maple is particularly adapted to the freeze-thaw cycles, periodic drought, and rocky, shallow soils of the Intermountain West. It grows from about 4,500 to 8,000 feet elevation, finding its sweet spot on north- and east-facing slopes where winter snow lingers and summer sun is less intense. Its drought tolerance — far greater than eastern maples — allows it to persist on rocky canyon walls where soil depth is minimal and rainfall averages just 12–18 inches annually.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Big Tooth Maple: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Big Tooth Maple is one of the best native trees for Intermountain West gardens, offering spectacular four-season interest combined with genuine drought tolerance once established. It is significantly easier to grow than eastern maples in the region’s dry climate and alkaline soils.

Light

Big Tooth Maple performs best in full sun, where it develops its densest canopy and most brilliant fall color. It also tolerates partial shade, particularly in afternoon — in the wild, many specimens grow on canyon walls with half-day sun. In too much shade, the fall color is less intense and the tree may become more open and leggy. For optimal autumn displays, plant in a location receiving at least 6 hours of direct sun.

Soil & Water

One of Big Tooth Maple’s greatest virtues is its adaptability to the rocky, shallow, often alkaline soils of the Intermountain West. It thrives in well-drained, gravelly or loamy soils and is far more tolerant of alkalinity than eastern maples. Once established (usually 2–3 years), it requires minimal supplemental irrigation — surviving on natural precipitation in most of its range. During establishment, water weekly to every 10 days. Avoid overwatering or poorly drained soils, which can cause root rot. Mulch with 2–3 inches of wood chips to retain moisture and insulate roots.

Planting Tips

Plant in fall or early spring for best establishment. Container-grown stock is most commonly available; bare root trees transplant well if planted promptly. Choose a location with good air circulation to prevent fungal issues. Space trees 15–25 feet apart for a naturalistic grove. Big Tooth Maple is relatively slow-growing (1–2 feet per year), so patience is rewarded with a long-lived landscape asset. In exposed sites, a temporary windbreak may help young trees establish in harsh winters.

Pruning & Maintenance

Big Tooth Maple requires minimal pruning. Remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter before bud break. If you wish to develop a single-trunk tree form (rather than multi-stemmed shrub), select the strongest central leader early and remove competing stems gradually over several years. The tree is generally pest- and disease-resistant in its native range. Verticillium wilt and anthracnose can occasionally occur but are rarely fatal to well-established specimens.

Landscape Uses

- Specimen tree — planted alone for spectacular fall color display

- Canyon and slope plantings — excellent for dry, rocky sites

- Wildlife habitat — seeds, foliage, and cover for birds and mammals

- Native shade tree — for patios, lawns, and street plantings in the Intermountain West

- Erosion control — the spreading root system stabilizes slopes

- Riparian restoration — along canyon streams and intermittent drainages

- Xeriscape plantings — low water once established

Fire Ecology

Big Tooth Maple is considered fire-adapted — it resprouts vigorously from the root crown following top-kill by fire. In the Intermountain West, the species commonly occurs in areas with moderate fire return intervals (25–50 years) and is an important component of canyon chaparral communities that depend on periodic fire for regeneration and vigor.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Big Tooth Maple is a wildlife powerhouse in the otherwise often sparse canyons and foothills of the Intermountain West, providing food, cover, and habitat structure that is disproportionate to its modest size.

For Birds

The winged samaras (seeds) are relished by Evening Grosbeaks, Pine Siskins, Black-capped Chickadees, and various finches and sparrows, especially in autumn and winter when other food is scarce. The dense canopy and multi-stemmed growth form provides excellent nesting habitat for many cavity-nesting and cup-nesting birds. In spring, the flowers attract insects that become food for warblers and other insectivorous migrants passing through the canyons.

For Mammals

Mule Deer and Elk browse the leaves and twigs extensively, particularly in spring and summer when the foliage is nutritious and accessible. Pronghorn browse the leaves in areas where ranges overlap. Squirrels, chipmunks, and mice cache the seeds for winter food. Black Bears occasionally feed on the seeds and foliage. The dense thickets created by Big Tooth Maple provide crucial thermal cover and bedding areas for deer during winter in canyon environments.

For Pollinators

The early spring flowers provide nectar and pollen for bumblebees, native mining bees, and early-season flies and beetles that emerge before most other blooms are available in canyon environments. The simultaneous leaf-out and flowering creates a particularly valuable early-season resource for pollinators emerging from winter.

Ecosystem Role

In canyon ecosystems, Big Tooth Maple plays a critical role as a mid-story tree that bridges the gap between the riparian shrub layer and tall cottonwood-willow overstory. Its rapid sprouting after disturbance (fire, flood, drought) makes it a resilient structural component of these systems. The leaf litter decomposes relatively quickly compared to conifers, contributing to the nutrient cycling that supports canyon biodiversity. The tree’s deep root system helps prevent erosion on otherwise unstable rocky slopes.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Indigenous peoples throughout the range of Big Tooth Maple developed numerous uses for this versatile tree. The Navajo used the bark and inner bark medicinally, and prepared decoctions to treat various ailments. The wood was used for tool handles, small implements, and fuel, as the dense hardwood burns hot and long. Some tribes ate the young leaves as a cooked green in spring.

The sap of Big Tooth Maple contains sugar but at lower concentrations than the eastern Sugar Maple — insufficient for commercial syrup production but known to Indigenous peoples who collected and concentrated it for sweetening foods. The Ute and other Great Basin tribes appreciated the tree’s shade in canyon environments during hot summer months, and the brilliant fall foliage was noted as a seasonal landmark and calendar indicator in traditional ecological knowledge.

Today, Big Tooth Maple is gaining popularity in sustainable western landscaping as awareness grows about its drought tolerance, wildlife value, and spectacular beauty. Nurseries across the Intermountain West are increasingly offering this species as an alternative to thirsty eastern maples or non-native ornamentals. Conservation organizations use it extensively in canyon and riparian restoration projects throughout its native range.

Frequently Asked Questions

How is Big Tooth Maple different from Sugar Maple?

Big Tooth Maple is a close western relative of Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum), but it is significantly smaller, more drought-tolerant, and more adapted to the dry, alkaline soils of the Intermountain West. Its leaves have slightly different proportions and larger teeth. Unlike Sugar Maple, it does not produce sap in quantities worth collecting for syrup. The fall colors are equally brilliant — if not more so in some years.

Where can I see Big Tooth Maple fall color in Utah?

The best displays are found in Hobble Creek Canyon, American Fork Canyon, Provo Canyon, and the lower Wasatch foothills near Brigham City and Logan. Colorado’s mountain canyons also offer spectacular displays, particularly around Glenwood Canyon and Mesa Verde.

Is Big Tooth Maple drought tolerant?

Yes — far more so than eastern maples. Once established (2–3 years), Big Tooth Maple survives on natural rainfall throughout much of its native range, which averages only 12–20 inches annually. In garden settings, established trees typically need watering only every 2–3 weeks during summer drought.

How fast does Big Tooth Maple grow?

It is a moderate grower, adding about 1–2 feet per year under ideal conditions. Growth is faster when planted in moist, partially shaded canyon conditions and slower on dry, exposed sites. It typically reaches its mature height of 20–30 feet in 15–25 years.

Can Big Tooth Maple grow in clay soils?

Big Tooth Maple strongly prefers well-drained soils and does not perform well in heavy clay that stays wet. Amending planting sites with gravel or coarse sand, or planting on slopes where water drains away, is recommended in clay-heavy soils. Root rot is the primary concern in poorly drained situations.