Singleleaf Pinyon (Pinus edulis)

Pinus edulis, commonly known as the Colorado Pinyon, Two-Needle Pinyon, or Pinyon Pine, is one of the most culturally, economically, and ecologically significant trees of the American Southwest. For thousands of years, the seeds of this compact native pine — known as “pine nuts” or “piñons” — have been the most important plant food in the diet of Indigenous peoples of the Colorado Plateau and Great Basin. The pinyon-juniper woodland that this tree co-dominates covers approximately 70 million acres of the American West, making it the largest forest type in the region and one of the most extensive in all of North America. Despite its modest stature (rarely exceeding 20 feet in typical conditions), Pinus edulis is one of the landscape-defining trees of the West, shaping both the physical and cultural character of the region more than any other single species.

The species name edulis — from Latin, meaning “edible” — refers directly to the large, nutritious seeds that distinguish this pine from all others. Each year, on irregular boom-and-bust cycles, pinyon pines produce cone crops that contain seeds so large, rich in fat and protein, and easy to harvest that they have sustained entire civilizations. The Ancestral Puebloans, Navajo, Ute, Paiute, and dozens of other peoples built seasonal economies around pine nut harvest, and the tradition continues today with commercial and subsistence harvesting throughout the Southwest.

Beyond its human significance, Pinyon Pine is an ecological foundation species. More than 40 bird species and numerous mammals depend on pinyon pine seeds during fall and winter. The Pinyon Jay — a remarkably intelligent corvid — has co-evolved with pinyon pines in one of the most complex bird-tree mutualisms known to science, playing the primary role in dispersing and caching pinyon seeds across the landscape. Without Pinyon Jays, the range of Pinus edulis would be dramatically contracted.

Identification

Colorado Pinyon is a slow-growing, drought-adapted pine that rarely exceeds 20 feet (6 m) in height under typical conditions, though exceptional specimens on favorable sites can reach 35 feet. The crown is broadly conical when young, becoming irregularly rounded to flat-topped with age. Trees may live 400–1,000 years, and some ancient specimens in protected canyon environments exceed 1,000 years in age. The species is the co-dominant tree of the pinyon-juniper woodland along with Utah Juniper (Juniperus osteosperma) and One-seed Juniper (J. monosperma).

Needles

The needles are the key identification feature: Pinus edulis bears needles in bundles of 2 (sometimes 1–3 on the same tree), each needle 0.75–2 inches (2–5 cm) long, stiff, curved, and dark gray-green to blue-green. The bundles are dense and create a thick, lush appearance compared to many other pines. In the Intermountain West, P. edulis occurs alongside Singleleaf Pinyon (P. monophylla), which bears solitary needles — the two species overlap in parts of Nevada and Utah. The presence of needles typically in pairs is the definitive field distinction.

Bark

The bark of mature trees is gray-brown to reddish-brown, furrowed into interlacing flat-topped ridges with scaly plates. Young trees have smoother, grayish bark. The overall bark texture gives older trees a gnarled, ancient appearance that is characteristic of the pinyon-juniper woodland aesthetic. The tree exudes aromatic resin from wounds, contributing to the distinctive pine-resin scent that perfumes pinyon-juniper woodlands.

Cones & Seeds

The cones are oval to almost round, 1.5–2 inches (4–5 cm) long, with thick, rounded scales. They mature in late summer of the second year and open to release the large, wingless (or nearly wingless) seeds in late August through October. Each seed (pine nut) is 0.4–0.6 inches (10–15 mm) long — large relative to most pine seeds — oval, tan to brown, with a hard shell and a rich, buttery kernel inside. The seeds are extremely nutritious: approximately 60% fat, 18% protein, and 20% carbohydrate by weight. A single large pinyon pine can produce 5–50 pounds of seeds in a good crop year, though crops occur on irregular 2–7 year cycles.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Pinus edulis |

| Family | Pinaceae (Pine) |

| Plant Type | Evergreen conifer tree |

| Mature Height | 20 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low (Drought Tolerant) |

| Growth Rate | Very slow (3–6 in/year) |

| Cone & Seed Time | Cones ripen August–October (irregular cycles) |

| Wildlife Value | Critical — 40+ bird species; all major mammals |

| Lifespan | 400–1,000+ years |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–8 |

Native Range

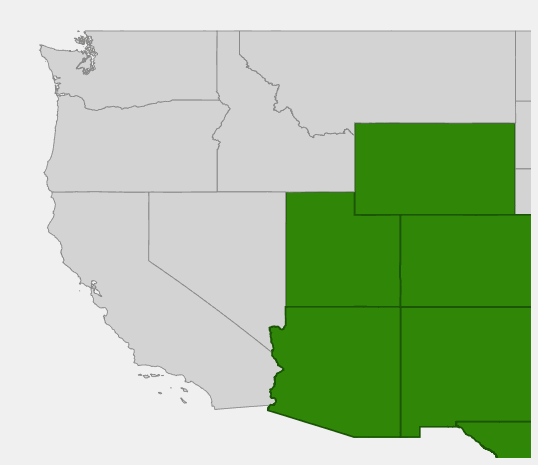

Colorado Pinyon is native to the Colorado Plateau and southern Rocky Mountain region, with a range centered on Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico, extending into eastern Nevada, extreme western Texas, and southwestern Wyoming. Within this range, it forms extensive woodlands on plateaus, mesas, canyon rims, and rocky slopes from about 4,500 to 8,000 feet elevation — the classic “pinyon-juniper zone” that blankets much of the Four Corners region and defines the characteristic landscape of the Colorado Plateau.

The pinyon-juniper woodland is the largest forest type in the American West by area, covering an estimated 70+ million acres across ten western states. In this woodland, Pinus edulis is the dominant pine species from western Colorado, Utah, and northern New Mexico eastward; Singleleaf Pinyon (P. monophylla) dominates in Nevada and California to the west, and One-needle Pinyon (P. monophylla × P. edulis intergrades and pure populations) occurs in a broad transition zone. The two species co-occur in parts of Nevada and Utah where ranges overlap.

Concern about the future of pinyon-juniper woodlands has increased dramatically in recent decades. Severe drought events — particularly those of 2002–2003 and 2011–2013 — combined with bark beetle outbreaks triggered by drought stress, killed millions of pinyon pines across the Southwest, creating one of the largest recorded tree-mortality events in North American history. Climate change projections suggest that conditions favorable to mass mortality events will become more frequent, raising serious conservation concerns for this foundational ecosystem.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Singleleaf Pinyon: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Pinyon Pine is a superb native tree for low-water landscapes in the West — beautiful, long-lived, and deeply satisfying to grow. The primary challenge is patience: this is a slow-growing tree that rewards long-term investment with centuries of beauty and ecological value.

Light

Full sun is essential — Pinyon Pine evolved in the open, sun-exposed pinyon-juniper woodland and does not tolerate shade. Plant in the most exposed, open location available. On south- and west-facing slopes, this tree reaches its peak performance. Even in the deep shade of adjacent buildings or trees for only part of the day, growth and health can be compromised over time.

Soil & Water

Pinyon Pine is among the most drought-tolerant conifers in North America — in its native range, it survives annual precipitation as low as 10 inches. It requires fast-draining, gravelly, sandy, or rocky soil and absolutely cannot tolerate wet or compacted conditions. On heavy clay soils, growing on raised berms or in amended beds is essential. Once established (2–3 years), supplemental irrigation is rarely needed except during extreme, prolonged drought. Overwatering — particularly in poorly-draining soils — is the primary cause of death in cultivated specimens. Root rot, often accelerated by the bark beetles that exploit drought-stressed trees, is the main health concern.

Planting Tips

Plant small container stock (1–5 gallon) in spring. Pinyon Pine develops a deep taproot that makes transplanting of large specimens difficult and often fatal. Small plants establish far better than large ones and will often outperform larger transplants within 5 years. Set the root crown at or slightly above grade to ensure water drains away from the base. Apply a 2–3 inch gravel mulch ring to maintain soil temperature and moisture balance while ensuring the crown stays dry. Do not add amendments to the planting hole — the tree is adapted to poor, unamended soil.

Pruning & Maintenance

Pinyon Pine requires minimal pruning. Remove dead branches in early summer when bark beetles are most active (dead wood attracts beetles). Do not prune in late summer or fall, when sap flow is lowest and wound susceptibility to pathogens is highest. Avoid making large cuts — the tree heals slowly. The natural form is beautiful and should be preserved; aesthetic pruning is rarely necessary or advisable. In most western climates, established trees need virtually no maintenance beyond removal of obviously dead wood.

Landscape Uses

- Specimen tree — for year-round evergreen structure and wildlife value

- Naturalistic xeriscape in a pinyon-juniper theme

- Wildlife habitat — pine nuts attract an extraordinary diversity of birds and mammals

- Privacy screen or windbreak — dense evergreen foliage

- Slope stabilization on dry, rocky hillsides

- Historical and cultural landscapes connecting to the deep human heritage of the Southwest

- Long-term investment — a tree that outlives its planters many times over

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Pinyon Pine supports one of the most diverse and complex wildlife communities of any tree species in western North America. Its large, nutritious seeds function as a keystone food resource for an extraordinary array of species.

For Birds

Over 40 bird species depend on pinyon pine seeds as a primary food source, including the Pinyon Jay, Clark’s Nutcracker, Steller’s Jay, Western Scrub-Jay, Band-tailed Pigeon, White-breasted Nuthatch, Pygmy Nuthatch, and many others. The Pinyon Jay has co-evolved with this tree over millions of years — its specialized beak (lacks the hook common to other jays) is perfectly designed for extracting pinyon seeds, and its remarkable ability to cache seeds miles from the parent tree is the primary mechanism of long-distance seed dispersal. Without Pinyon Jays caching and occasionally forgetting seeds, the pinyon pine’s range expansion following the last ice age would have been far more limited.

For Mammals

Mule Deer, Elk, and Pronghorn browse the young needles and foliage. Black Bears, Coyotes, Foxes, Raccoons, and Ringtails consume the seeds. Squirrels (particularly the Abert’s Squirrel in Colorado), chipmunks, and kangaroo rats are voracious seed hoarders. In boom years, the entire food web of the pinyon-juniper woodland responds dramatically to the abundant seed crop. The dense evergreen canopy provides essential thermal cover and roosting habitat for wintering birds.

Ecosystem Role

As the dominant tree of the second-largest forest type in the American West, Pinus edulis provides the structural foundation for an entire ecosystem encompassing tens of millions of acres. Its relationship with Pinyon Jays represents one of the most intricate and well-studied plant-animal mutualisms in North America. The trees are also critical for the diverse community of mycorrhizal fungi associated with their roots — fungi that support the nutrition of many other plants in the woodland ecosystem.

Cultural & Historical Uses

No plant in the American Southwest has a deeper or more sustained relationship with human civilization than the Pinyon Pine. For at least 5,000 years — and almost certainly much longer — the pine nut has been the most important plant food across a vast swath of the Colorado Plateau and Great Basin. Archaeological sites throughout the Four Corners region document the central role of pine nut harvesting in Ancestral Puebloan culture. Storage jars recovered from sites across Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico regularly contain charred pine nut fragments, and grinding stones show the characteristic wear patterns from processing pine nuts into flour and meal.

For the Navajo, Ute, Paiute, Shoshone, and many other peoples of the region, the annual pine nut harvest was a major cultural event — entire extended families and bands traveled to productive pinyon groves in the fall, camping for weeks while harvesting and processing the seeds. Surplus pine nuts were carefully stored for winter, forming a critical nutritional safety net during cold months when other foods were scarce. The ecological knowledge required to predict and access productive groves — knowledge accumulated and passed down through generations of careful observation — represents one of the most sophisticated bodies of traditional ecological knowledge in North America.

Today, the commercial pine nut harvest from wild trees remains significant, though much of the market is now supplied by imported seeds from China and Pakistan. Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico still host active wild harvest operations, and the tradition of family harvesting continues in Indigenous communities. Pinyon pine is also widely used for firewood, fence posts, and wood crafts, and pinyon resin has traditional uses in waterproofing and adhesive applications. The wood smoke from pinyon fires has a distinctive, beloved fragrance that is deeply evocative of the Southwest and is used in commercial incense and firewood products.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take for Pinyon Pine to produce pine nuts?

Patience is required — most pinyon pines don’t begin producing significant cone crops until they are 25 years old, and peak production doesn’t occur until 75–100 years. In a garden setting, expect to wait at least 20 years for any meaningful harvest. The trees are worth planting for their beauty, wildlife value, and cultural significance even if you’ll never personally harvest the pine nuts.

How do you harvest pine nuts from wild trees?

Traditionally, cones are collected in August–September before they fully open, then dried in the sun to release the seeds. The seeds are then roasted in hot coals or a dry pan, shaken with the shells on a flat surface, and the shells cracked between stones or with modern nut crackers. On public lands in the West, personal-use harvesting of pinyon nuts is generally allowed up to specified limits; check applicable federal and state regulations.

Is Pinyon Pine drought tolerant?

Extremely so. It grows naturally in areas with as little as 10 inches of annual rainfall and can go extended periods (months) without any precipitation. However, severe multi-year drought combined with high temperatures — increasingly common with climate change — can exceed even this tree’s tolerances, as demonstrated by the mass mortality events of the 2000s and 2010s.

How big does Pinyon Pine get?

Typically 15–20 feet in most garden conditions; occasionally to 35 feet on excellent sites. The tree is very slow-growing — adding perhaps 3–6 inches per year — so it takes many decades to reach mature size. In garden settings, this slow growth is often an asset, as the tree stays small and manageable for many years.

What kills pinyon pine?

Bark beetles (primarily the pinyon ips, Ips confusus) are the primary killer. Beetles attack drought-stressed trees — trees that cannot produce enough resin to “pitch out” the beetles. The solution is ensuring adequate moisture during establishment and avoiding overwatering or waterlogging. A healthy, non-stressed tree can typically defend itself against beetle attack.