Western Juniper (Juniperus occidentalis)

Juniperus occidentalis, commonly known as Western Juniper, is one of the most remarkable and ecologically significant trees of the Great Basin and Pacific Northwest. While it may not attract immediate attention with showy flowers or brilliant fall color, Western Juniper commands deep respect for what it represents: longevity, resilience, and adaptation taken to extraordinary extremes. Ancient specimens of this tree — some exceeding 3,000 years of age — are among the oldest living things on the continent, their massively twisted, orange-bark trunks and broadly spreading crowns representing millennia of survival through drought, fire, frost, and time.

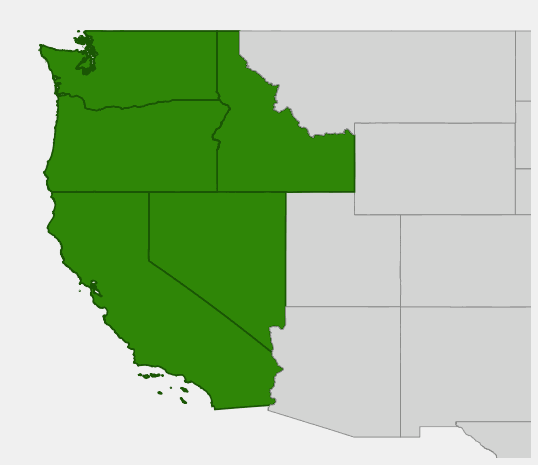

Native to Oregon, Washington, California, Idaho, and Nevada, Western Juniper dominates vast areas of the arid high desert, particularly in central and eastern Oregon where it forms extensive pure woodlands on the pumice plains and basalt plateaus of the Great Basin margin. Unlike many trees that require specific soil or moisture conditions, Western Juniper tolerates an extraordinary range of substrates — basalt, pumice, limestone, serpentine, clay, sand — and survives annual precipitation as low as 8–10 inches. These adaptations, combined with the tree’s prolific seed production and bird-assisted dispersal, have allowed Western Juniper to expand its range dramatically over the past 150 years in response to fire suppression and grazing changes — a range expansion that has become a significant ecological management concern in the region.

In the garden and landscape, Western Juniper is an outstanding choice for dry, exposed sites where few trees survive. Its evergreen foliage, interesting bark, sculptural growth form, and exceptional wildlife value make it a valuable native tree for xeriscape plantings throughout the Intermountain West and Pacific Northwest’s eastern regions. The blue-green “berries” (technically cones) provide critical winter food for dozens of bird species and mammals, making Western Juniper one of the most important food-producing trees of the region.

Identification

Western Juniper is a slow-growing evergreen tree that varies considerably in size and form depending on age and growing conditions. Young trees are conical to broadly pyramidal; mature trees develop broadly rounded to flat-topped crowns on stout, often twisted, massive trunks. In harsh sites — exposed ridges, rocky outcrops — trees may remain large shrubs for centuries before developing tree form. In productive valley-margin sites with better soils and more moisture, trees can reach 30–40 feet tall with trunks 3–5 feet in diameter after many centuries.

Bark

The bark of mature Western Junipers is among the most beautiful of any western tree. The outer bark is shredding, fibrous, gray-brown to reddish-brown — on older trees, large sections peel away to reveal the smooth, cinnamon-orange inner bark that gives ancient specimens their warm, glowing color. The deeply furrowed, shaggy outer bark is an important habitat feature, providing shelter for birds, insects, and small mammals. Ancient specimens can have trunks with massive, deeply spiraling furrows that suggest incredible age and struggle.

Foliage

The foliage consists of tiny, scale-like, overlapping leaves 1/16 to 1/8 inch long, tightly appressed to the branches to form rope-like sprays. The foliage is gray-green to blue-green, with a distinctive sharp, piney-juniper fragrance when crushed. On young vigorous shoots, some leaves may be awl-shaped (needle-like) rather than scale-like. The foliage is less dense than some other junipers, giving mature trees an open, airy appearance in contrast to the dense junipers of the Colorado Plateau.

Berries (Cones)

The “berries” are technically fleshy seed cones — berry-like cones where the scales have fused into a soft, waxy, bluish-black structure. Each berry is about 1/4 to 3/8 inch (6–9 mm) in diameter, covered with a distinctive powdery blue-white bloom (waxy coating). They take two years to mature from pollination and ripen in late summer to fall of the second year. Inside each berry are 1–3 small, brown seeds. The berries have a distinctive resinous, aromatic flavor and are the plant’s most important wildlife food resource.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Juniperus occidentalis |

| Family | Cupressaceae (Cypress) |

| Plant Type | Evergreen conifer tree |

| Mature Height | 20–30 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low (Drought Tolerant) |

| Growth Rate | Very slow (ancient specimens 3,000+ years) |

| Berry (Cone) Time | Ripens August–October (second year) |

| Wildlife Value | Critical winter food & cover; 50+ bird species |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 5–9 |

Native Range

Western Juniper is native to the Pacific Northwest and Great Basin region, with a range centered on central and eastern Oregon, extending into northeastern California, northwestern Nevada, southern and central Idaho, and eastern Washington. It is the dominant tree species of vast areas of the Oregon outback — the high desert plateaus of Harney, Lake, and Malheur counties in Oregon support some of the world’s most extensive western juniper woodlands, covering millions of acres.

Historically, Western Juniper was less abundant and more restricted to rocky outcrops, rim rocks, and slopes where fire could not reach it regularly. The suppression of natural fire cycles beginning in the late 1800s — combined with livestock overgrazing that removed the fine fuels (grasses) needed to carry fire — allowed juniper to expand dramatically from its historic refuge habitats into adjacent grasslands, shrublands, and meadows. This expansion has accelerated in the 20th century; studies in Oregon document that juniper woodland area has expanded by 500–900% since Euro-American settlement, representing one of the most dramatic vegetation changes in the American West.

Ancient stands of Western Juniper in the most inhospitable sites — rocky summit ridges, exposed basalt outcrops — are among the most remarkable natural phenomena of the Great Basin. Trees here, protected from fire by the rocky terrain and limited fuel accumulation, reach ages of 1,000–3,000 years and develop extraordinary sculptural forms with massive, orange-barked trunks and sweeping, gnarled crowns that have endured countless droughts, volcanic eruptions, and climate fluctuations since the Bronze Age.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Western Juniper: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Western Juniper is one of the most rugged and self-sufficient native trees for western landscapes. Once established, it is essentially maintenance-free and provides decades of evergreen structure, wildlife habitat, and unique beauty.

Light

Full sun is essential. Western Juniper evolved in the open, wind-swept high desert and develops its best form and health in fully exposed conditions. Shading by adjacent trees or buildings causes gradual decline. Choose a fully open, unobstructed planting location. South- or west-facing slopes with excellent exposure and drainage are ideal.

Soil & Water

Western Juniper is extraordinarily drought tolerant — among the most drought-resistant trees in North America. It naturally grows in areas receiving as little as 8–12 inches of annual precipitation and handles the fierce summer heat and desiccating winds of the high desert with aplomb. It thrives in a wide range of soil types including sand, gravel, basalt, pumice, and clay, as long as drainage is adequate. It handles both acidic and alkaline conditions. During establishment, water every 1–2 weeks; after the first season, most established trees need no supplemental irrigation in areas receiving 10+ inches of annual rainfall. In very hot, dry garden situations, occasional deep watering in summer may benefit young trees.

Planting Tips

Plant in spring or fall. Small container stock (1–5 gallon) transplants best; larger junipers with root-pruned or disturbed root systems may take several years to recover. Do not amend the planting hole — the tree performs best in native, unamended soil. Set the root crown at grade. Mulch with gravel rather than organic material. Stake only if necessary for wind stability — remove stakes after the first season to encourage strong trunk development.

Pruning & Maintenance

Western Juniper requires essentially no pruning in natural garden settings. The natural form is beautiful and should be preserved. Remove dead branches if they occur (usually after extreme drought or insect attack). Avoid creating large wounds that would attract juniper bark beetles, particularly during summer. The tree is generally pest-resistant when healthy and well-sited. Juniper mistletoe (Arceuthobium occidentale) can parasitize stressed trees — maintaining tree vigor through appropriate siting is the best defense.

Landscape Uses

- Specimen tree — for dramatic, sculptural presence and year-round interest

- Windbreak and living fence — dense, drought-tolerant

- Wildlife habitat — berries and dense cover for birds and mammals

- Xeriscape anchor — the structural backbone of water-wise landscapes

- Fire-prone areas — junipers that are properly sited and maintained away from structures

- Historical and naturalistic landscapes evoking the Great Basin high desert

- Long-term specimen planting for future generations

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Western Juniper is one of the most important wildlife trees of the Pacific Northwest and Great Basin, providing food and cover that is especially critical during winter when other resources are scarce.

For Birds

Over 50 bird species consume Western Juniper berries, making this tree one of the most important avian food plants in its region. American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Bohemian Waxwings, Townsend’s Solitaires, Western Bluebirds, and numerous thrushes are major consumers. Townsend’s Solitaire, in particular, has evolved a remarkable relationship with Western Juniper — these birds establish winter territories specifically around productive juniper trees, defending berry supplies against other birds to ensure their own survival through harsh winters. The dense, evergreen foliage of Western Juniper provides essential roosting and nesting habitat throughout the year, and the tree is a preferred nesting site for Great Horned Owls and various hawk species.

For Mammals

Mule Deer browse the foliage intensively, particularly in winter when other browse is snow-covered. Coyotes, foxes, raccoons, and bears consume the berries. Chipmunks and ground squirrels cache the berries. The dense, evergreen canopy creates warm thermal refugia beneath it that deer, elk, and smaller mammals seek during cold weather. Porcupines occasionally gnaw the bark.

For Pollinators

Junipers are wind-pollinated (dioecious), so they don’t offer traditional nectar or pollen rewards to bees. However, the tree supports numerous insects associated with its foliage, bark, and berries — beetles, moths, aphids, scale insects — that in turn support insectivorous birds and bats. The structural complexity of old-growth juniper stands supports considerably greater invertebrate diversity than young, expanding juniper woodland.

Ecosystem Role

In the Great Basin and Pacific Northwest high desert, Western Juniper woodlands provide the most significant structural vegetation in an otherwise open landscape. The trees create islands of biological activity, concentrating wildlife, protecting soil from erosion, and moderating the microclimate beneath their canopies. Ancient individual trees — thousands of years old — are irreplaceable ecological structures that support unique communities of lichens, insects, and cavity-nesting birds that require the deep bark furrows and large cavities that only develop in very old specimens.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Western Juniper has been used by Indigenous peoples throughout its range for thousands of years. The berries — though quite resinous and not particularly palatable to humans — were used as flavoring agents in cooking and food preparation by the Paiute, Shoshone, Modoc, Klamath, and various other peoples. More commonly, the berries were used medicinally: preparations were used to treat colds, rheumatism, urinary tract infections, and as a general tonic. The berries were also burned as incense in ceremonial contexts, and the distinctive aromatic smoke was believed to have cleansing and protective properties.

The wood of Western Juniper is extremely rot-resistant — fence posts made from juniper heartwood can last 50–100 years in the ground without treatment, making it highly valued for traditional and modern fencing. The fibrous, shreddy bark was used by Indigenous peoples to make rope, matting, clothing, and padding for baby carriers. The bark is also highly flammable and is an excellent fire-starting material — Indigenous fire-making often used juniper bark as tinder.

In the modern era, Western Juniper wood has found uses in furniture making, carving, and artisan woodworking, valued for its beautiful reddish-brown heartwood with dramatic grain patterns. The essential oils from juniper foliage and berries have traditional and modern aromatherapy applications. The conservation of ancient Western Juniper stands — particularly the old-growth specimens on protected ridge tops in eastern Oregon — has become increasingly important to Indigenous peoples and conservationists who recognize these ancient trees as irreplaceable living heritage.

Frequently Asked Questions

How old can Western Juniper get?

Ancient specimens have been documented at 3,000+ years old, making them among the oldest living trees in North America. The oldest confirmed specimen was over 3,000 years old when studied, with tree-ring records extending back to before 1000 BCE. These ancient trees occur primarily on rocky outcrops where fire and disturbance cannot reach them.

Is Western Juniper invasive?

Within its native range, Western Juniper has expanded dramatically in the past 150 years due to fire suppression and altered grazing patterns — a process called “juniper encroachment” that is a major land management concern in Oregon, Idaho, and Nevada. This expansion converts sagebrush steppe and grasslands to dense juniper woodland, reducing habitat for species like Greater Sage-Grouse. However, the tree is not invasive outside its native range and is a valuable native plant in appropriate contexts.

Can you eat Western Juniper berries?

The berries are technically edible but quite resinous and bitter — primarily useful as a flavoring agent rather than a food. Gin is flavored with Common Juniper (J. communis) berries, not Western Juniper. Indigenous peoples used small quantities of Western Juniper berries medicinally and as a flavoring, but they were not a primary food source. Leave them for the wildlife — over 50 bird species depend on them.

Is Western Juniper the same as Utah Juniper?

No. Western Juniper (Juniperus occidentalis) is the dominant juniper of the Pacific Northwest and Great Basin margin (Oregon, Washington, northern California, Nevada, Idaho). Utah Juniper (Juniperus osteosperma) co-dominates the Colorado Plateau pinyon-juniper woodland further south and east (Utah, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico). The two species have different ranges that overlap only marginally in parts of Nevada and Idaho.

Why are some Western Junipers dying in Oregon?

Two main causes: drought-related stress (increasingly severe with climate change) and bark beetle attack on drought-stressed trees. The trees that are dying are typically those growing in more expanded, marginal areas rather than in the core historic range on rocky outcrops. This is somewhat paradoxical — the expanded juniper woodland created by fire suppression may be less climatically resilient than the ancient refuge populations.