Bitterbrush (Purshia tridentata)

Purshia tridentata, commonly known as Bitterbrush or Antelope Bitterbrush, is one of the most ecologically important shrubs of the American West. A member of the Rosaceae (rose) family, this tough, long-lived shrub dominates vast swaths of sagebrush steppe and pinyon-juniper woodland from the Great Basin to the Rocky Mountain foothills. Its name comes from the intensely bitter taste of its foliage — a chemical defense that paradoxically makes it one of the most important winter browse plants for mule deer, pronghorn, and elk throughout its range.

Every spring, Bitterbrush transforms the dry hillsides and plains of the Intermountain West with an explosion of bright yellow, five-petaled flowers that carpet the landscape from April through June. These flowers are a critical nectar source for native bees, butterflies, and other pollinators in an ecosystem where bloom time is short and competition for nectar is fierce. The seeds that follow are eagerly cached by Chipmunks and Pinyon Jays, which inadvertently plant new shrubs across the landscape — making Bitterbrush one of the most important seed-dispersed shrubs in the region.

Beyond its extraordinary ecological value, Bitterbrush is a highly drought-tolerant, fire-adapted shrub that plays a crucial role in rangeland stabilization, erosion control, and post-fire recovery. Its deep taproot system anchors sandy soils, its nitrogen-fixing root associations enrich poor soils, and its dense branching structure creates shelter for small mammals and ground-nesting birds. For any native plant garden, restoration project, or wildlife habitat in the Intermountain West, Bitterbrush is an indispensable cornerstone species.

Identification

Bitterbrush grows as a spreading, many-branched deciduous shrub typically reaching 2 to 6 feet tall (occasionally to 10 feet in favorable sites), with a rounded to irregular crown. The branches are rigid and somewhat spiny, covered in grayish-brown bark that becomes shreddy and furrowed with age. Young twigs are glandular-hairy and aromatic when crushed.

Leaves

The leaves are the key identification feature: small, wedge-shaped, and three-lobed at the tip (hence the species name tridentata, meaning “three-toothed”). Each leaf is ¼ to ¾ inch (6–20 mm) long, dark green and somewhat sticky above, paler and hairy below, with conspicuous veins. Leaves are clustered in short spurs along the branches and are aromatic. They are tardily deciduous, persisting through much of winter in mild areas. The bitter taste of the leaves comes from terpenes and phenolic compounds that inhibit digestibility — yet browsing ungulates, especially mule deer, consume enormous quantities in winter when other food is scarce.

Flowers

The flowers are bright golden-yellow, ½ to ¾ inch (12–20 mm) across, with five rounded petals in the classic rose family arrangement. They bloom prolifically from April through June depending on elevation, emerging from the leaf axils singly or in small clusters. The yellow flowers cover the entire shrub and are highly fragrant, attracting bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds. Bitterbrush flowers are produced in such abundance that the shrub appears almost entirely yellow during peak bloom.

Fruit & Seeds

The fruit is a small, dry, leathery achene (a seed-like nutlet), about ¼ inch (6 mm) long, covered with fine hairs. It contains a single seed rich in protein and fat. The nutlets are cached by Chipmunks (Tamias spp.), Pinyon Jays (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus), and other animals — many are forgotten and germinate the following spring, making Bitterbrush one of the most animal-dispersed shrubs in the Great Basin ecosystem. The seeds remain viable in caches for 1–3 years.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Purshia tridentata |

| Family | Rosaceae (Rose) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 2–6 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Very Low (Xeric/Extremely Drought Tolerant) |

| Bloom Time | April – June |

| Flower Color | Bright yellow |

| Soil Type | Sandy, gravelly, well-drained; poor soils |

| Wildlife Value | Very High — deer, elk, pronghorn, birds, bees |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–8 |

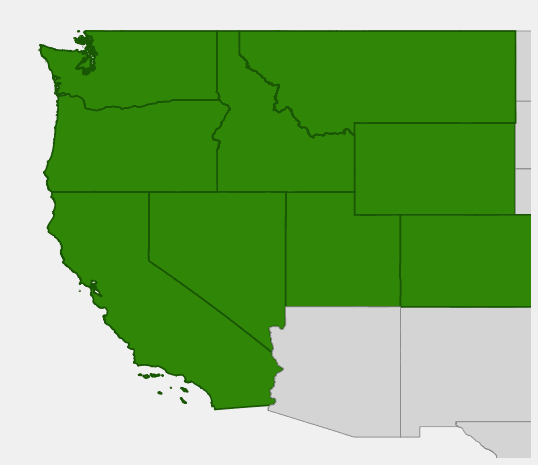

Native Range

Bitterbrush is native to western North America, ranging from British Columbia south through Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, California, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico. It is one of the dominant shrubs of the Great Basin and Columbia Basin, covering millions of acres of sagebrush steppe and dry foothills from low desert elevations to subalpine zones. The species extends from approximately 2,000 to 10,000 feet elevation, with the densest stands typically found between 4,000 and 8,000 feet.

In its natural habitat, Bitterbrush forms extensive communities on dry, south- and west-facing slopes with sandy or gravelly soils. It is most commonly found in association with Big Sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), Bluebunch Wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), and various bunch grasses. At higher elevations, it grows with Ponderosa Pine (Pinus ponderosa) and Mountain Mahogany (Cercocarpus spp.). Bitterbrush is notably absent from clay-heavy soils and poorly drained sites.

The species is well adapted to fire — it resprouts vigorously from the root crown after low-intensity fires and regenerates from seed after more intense burns. However, it is sensitive to heavy livestock grazing, which can reduce stands significantly over time. Healthy Bitterbrush stands are a key indicator of good range condition throughout the Great Basin.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Bitterbrush: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Bitterbrush is an exceptionally tough and adaptable shrub that thrives on neglect once established. It is perfectly suited to the challenging conditions of the Intermountain West — extreme temperatures, drought, poor soils, and wind — and requires minimal care after the first year or two of establishment.

Light

Bitterbrush demands full sun. It grows best with at least 6–8 hours of direct sunlight daily and will become leggy and bloom poorly in shade. Plant it on south- or west-facing slopes for best results, mimicking its natural habitat on open, exposed hillsides and flats. In shadier conditions, Bitterbrush loses its vigor and becomes susceptible to disease.

Soil & Water

This is one of the most drought-tolerant shrubs native to western North America. Bitterbrush thrives in poor, dry, sandy or gravelly soils with excellent drainage — it will not tolerate wet or clay-heavy soils. Once established (typically after 2–3 years), it requires virtually no supplemental watering in its native range. During the establishment period, water deeply but infrequently (every 2–3 weeks) to encourage deep root development. The deep taproot system allows it to access water from deep in the soil profile during dry periods.

Planting Tips

Plant Bitterbrush from container stock in fall or early spring. Choose the sunniest, best-draining spot available. Amend heavy clay soils with coarse sand and gravel before planting — or better yet, choose a naturally sandy site. Space shrubs 4–8 feet apart for a natural-looking grouping. Seed sowing is also effective: collect seeds in late summer and plant directly in fall to allow natural stratification over winter.

Pruning & Maintenance

Bitterbrush requires minimal pruning. If rejuvenation is needed, it can be cut back heavily in late winter — it will resprout vigorously from the crown. Avoid summer pruning when plants are actively growing. Remove dead wood as needed. Do not fertilize — Bitterbrush has nitrogen-fixing root associations and grows naturally in nutrient-poor soils; fertilizing can actually harm it by promoting lush, weak growth susceptible to disease.

Landscape Uses

- Wildlife gardens — critical winter browse for deer, elk, and pronghorn

- Dry slope stabilization and erosion control on rocky hillsides

- Xeric borders and mixed shrub plantings with sagebrush and native grasses

- Restoration plantings on degraded rangeland and post-fire sites

- Pollinator gardens — prolific yellow flowers attract native bees in spring

- Naturalized areas and meadow edges in dry-climate gardens

Fire Ecology

Bitterbrush has a complex relationship with fire. Low-to-moderate intensity fires stimulate resprouting from the root crown, and new growth is highly nutritious and palatable to browsing animals. However, high-intensity fires or repeated burning can kill stands entirely. After fire, Bitterbrush is one of the first woody plants to reestablish from seed (dispersed by caching animals), playing a critical role in post-fire succession. Its recovery rate after fire is a key indicator of rangeland health in the Great Basin.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Few shrubs in the American West match Bitterbrush’s ecological importance. It is a keystone species of the Great Basin and Intermountain West, providing food, cover, and habitat structure across seasons for an extraordinary diversity of wildlife.

For Browsers & Mammals

Bitterbrush is critically important winter browse for Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus), Pronghorn Antelope (Antilocapra americana), Elk (Cervus elaphus), and Desert Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis). In snow-covered landscapes, Bitterbrush’s persistent leaves and twigs may provide the only readily accessible high-quality forage available. Populations of mule deer in the Great Basin are closely correlated with the abundance and condition of Bitterbrush stands. Jackrabbits, cottontails, and various rodents also browse the foliage and consume seeds.

For Birds

The seeds are cached by Chipmunks, Pinyon Jays, and Scrub-Jays, making Bitterbrush a critical food-storage plant in dry woodlands. The dense branching provides nesting sites and escape cover for Sage Sparrows, Brewer’s Sparrows, and other sagebrush-obligate birds. During bloom, the flowers attract a variety of birds that feed on the insects they attract.

For Pollinators

The abundant yellow flowers are a major nectar and pollen source for native bees (including Apis, Bombus, and many solitary bee species), butterflies, and beneficial wasps during spring. In the sparse, dry landscapes where Bitterbrush grows, its mass blooming events provide an essential burst of resources for early-season pollinators.

Ecosystem Role

Bitterbrush is a nitrogen-fixing shrub through associations with Frankia bacteria in root nodules, enriching the nutrient-poor soils of the Great Basin over time. Its leaf litter improves soil organic matter and supports soil invertebrate communities. The shrub’s dense canopy traps snow, increasing local soil moisture and creating cool microclimates that benefit understory plants and soil fauna. It is a foundational species of Great Basin ecosystem function.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Indigenous peoples of the Great Basin and Columbia Plateau, including the Paiute, Shoshone, Bannock, and Nez Perce peoples, had extensive knowledge of Bitterbrush and its uses. The seeds were ground into meal and used as a food source during times of scarcity. Medicinally, preparations from the bark and leaves were used as antiseptic washes, treatments for skin conditions, and fever reducers. The Shoshone used Bitterbrush bark in basket-making and weaving, taking advantage of its fibrous inner bark.

Bitterbrush has been a central species in western rangeland science since the early 20th century. The U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management conducted extensive studies on Bitterbrush beginning in the 1930s, recognizing its critical role in supporting deer and livestock populations across millions of acres of western rangelands. Research on its seed ecology, fire adaptation, and browse production continues today and informs rangeland management practices throughout the West.

In modern horticulture, Bitterbrush is increasingly valued as a drought-tolerant, wildlife-friendly landscape shrub for xeriscape gardens throughout the Intermountain West. Its low maintenance requirements, spectacular spring bloom, and exceptional wildlife value make it one of the best native shrubs available for dry-climate landscaping. Nurseries specializing in native plants often carry container-grown stock, and seed is commercially available for large-scale restoration projects.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it called Bitterbrush?

The common name comes from the intensely bitter taste of the leaves, caused by terpene and phenolic compounds. These chemicals are a defense against some browsers, but paradoxically, mule deer and other ungulates eat Bitterbrush heavily in winter — its nutritional value outweighs the bitterness when other food sources are scarce.

Is Bitterbrush good for deer?

Yes — Bitterbrush is one of the most important deer browse plants in the American West. Wildlife managers use Bitterbrush abundance as a proxy for mule deer habitat quality. Planting Bitterbrush is one of the best things you can do to support deer populations on your property.

How fast does Bitterbrush grow?

Bitterbrush is a moderately slow grower, typically adding 6–12 inches per year under favorable conditions. Growth is faster in the first few years with supplemental watering during establishment, then slows as the deep taproot system matures. Well-established plants are extremely long-lived, with some individuals exceeding 100 years.

Does Bitterbrush spread on its own?

Bitterbrush spreads via seeds cached and forgotten by chipmunks, Pinyon Jays, and other animals. It does not sucker or spread aggressively from the roots. New plants from seed can appear unpredictably wherever animals have cached and forgotten seeds — typically in protected spots under rocks or near logs.

Can Bitterbrush survive winter?

Yes — Bitterbrush is extremely cold-hardy (USDA Zones 3–8) and is adapted to harsh winters with deep snow and temperatures well below zero. In fact, it provides critical browse for deer and elk precisely because its stems and persistent leaves remain accessible above or through the snow during winter.