Silver Buffaloberry (Shepherdia argentea)

Shepherdia argentea, commonly known as Silver Buffaloberry or Thorny Buffaloberry, is one of the most ecologically significant and visually distinctive native shrubs of the Great Plains and Intermountain West. This robust, thorny deciduous shrub earns its common name from the brilliant silvery-white or silvery-gray sheen of its leaves — caused by dense, stellate (star-shaped) scales covering both leaf surfaces — and from its role as a major berry producer for wildlife in the arid plains and mountain valleys where it grows. Its bright red berries, produced in late summer, are consumed by a wide range of birds and mammals, and were a historically important food source for Indigenous peoples across the Plains and West.

Silver Buffaloberry grows naturally in a vast range from the Pacific Northwest east across the northern Great Plains and south into the Intermountain West, thriving in environments with cold winters, hot summers, seasonal drought, and soils ranging from rich bottomland alluvium to gravelly slopes. It is one of the few shrubs that fixes atmospheric nitrogen through a symbiotic relationship with Frankia bacteria in its root nodules — making it a soil enricher as well as a wildlife plant. This nitrogen-fixing ability allows it to grow in poor, disturbed soils where many other shrubs fail.

In the landscape, Silver Buffaloberry is valued for its silvery foliage — unlike any other native shrub — combined with its formidable thorns (which make an impenetrable defensive hedge), edible berries, exceptional cold-hardiness (to Zone 2), and outstanding drought tolerance. Few shrubs can match its combination of toughness and ornamental character in the challenging conditions of the Great Plains and Intermountain West.

Identification

Silver Buffaloberry grows as a large, multi-stemmed deciduous shrub reaching 6 to 20 feet (1.8–6 m) in height, often spreading equally wide through root suckering. The overall form is rounded to irregular, with a dense thicket of branches armed with sharp, stout thorns at the tips. The thorns are genuine spines — modified stems — rather than prickles (modified bark), making them very difficult to remove or avoid. The bark is reddish-brown on young stems, becoming gray and rougher with age.

Leaves

The leaves are one of the most distinctive features of Silver Buffaloberry. They are simple, opposite, 1 to 2½ inches (2.5–6 cm) long, oval to oblong, with a smooth margin. Both upper and lower surfaces are densely covered with silvery, star-shaped (stellate) scales — visible under magnification as a dense mat of overlapping scales — giving the entire leaf a brilliant silver-white or silvery-gray color that flashes in sunlight and remains attractive throughout the growing season. The silvery color distinguishes it from all other common shrubs in its range.

Flowers

Silver Buffaloberry is dioecious — male and female flowers are borne on separate plants, and both sexes must be present for fruit production. The flowers are tiny (2–4 mm across), yellowish, with no petals, appearing very early in spring (March–May) before the leaves emerge. They are wind-pollinated. Male flowers are slightly larger and more numerous; female flowers produce the berries. At least one male plant for every 4–6 female plants is recommended for good berry production.

Fruit

The berries are small, round drupes, about ¼ inch (6 mm) in diameter, bright red when ripe (occasionally yellow in some individuals). They are produced in dense clusters along the branches from July through September. The raw berries are intensely tart, with a unique bitter-sour taste attributed to a compound called saponin. After frost, the bitterness diminishes significantly and the berries become sweeter. They are an important wildlife food and were also consumed by Indigenous peoples after cooking or freezing.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Shepherdia argentea |

| Family | Elaeagnaceae (Oleaster Family) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 6–20 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate |

| Bloom Time | March – May |

| Flower Color | Yellow (inconspicuous) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–7 |

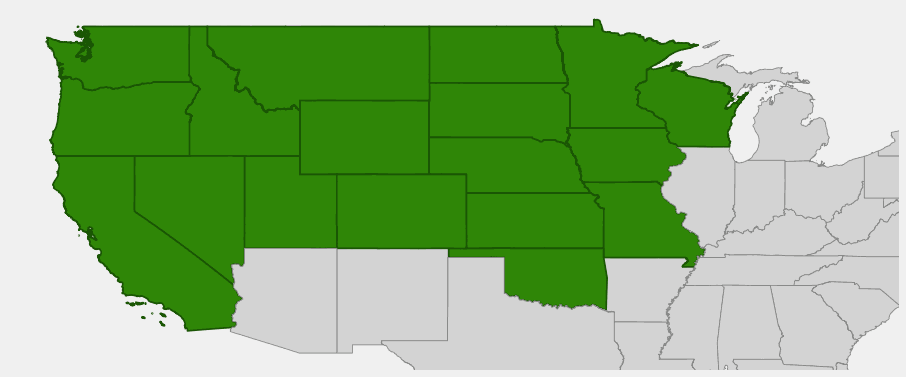

Native Range

Silver Buffaloberry has a remarkably extensive native range covering much of temperate North America from the Pacific Northwest east across Canada and the northern Great Plains to the Midwest. In the United States, it is found from Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and California east through Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas, and south through Nebraska, Kansas, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Missouri. It is absent from the humid Southeast and arid Southwest.

The species is most abundant and characteristic on the northern Great Plains — the Missouri River drainage system and associated valleys — where it forms dense thickets in river bottoms and coulees. The Lewis and Clark Expedition documented it extensively along the Missouri River in 1804–1806, and Lewis and Clark journals include detailed observations of the plant’s appearance and the importance of its berries to Plains tribes. On the Great Plains, Silver Buffaloberry is a signature plant of riparian shrublands and breaks along major rivers.

In the Intermountain West, Silver Buffaloberry grows in river valleys, canyon bottoms, and on dry, exposed slopes and ridges — it is one of the more drought-tolerant shrubs in the Elaeagnaceae. It also grows in transition zones between valley bottoms and adjacent dry uplands, contributing to shrubland ecotones. Its nitrogen-fixing ability allows it to colonize poor, disturbed soils where other shrubs are unable to establish.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Silver Buffaloberry: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Silver Buffaloberry is one of the toughest and most adaptable native shrubs available, thriving in conditions that would challenge or kill most ornamental plants. Once established, it is virtually indestructible.

Light

Full sun is preferred for best berry production and most compact, vigorous form. Silver Buffaloberry tolerates partial shade but produces fewer berries and becomes more open and leggy in low light. Plant where it receives at least 6 hours of direct sun daily, preferably 8 or more.

Soil & Water

Silver Buffaloberry thrives in a wide range of soils from dry, gravelly, or sandy to moderately moist clay, and tolerates alkaline, saline, and poor soils that challenge most other shrubs. Its nitrogen-fixing root nodules allow it to grow in low-nutrient soils without fertilizer. Once established, it tolerates extended drought well (rated Low to Moderate water needs). In extremely dry sites, occasional deep watering in summer helps maintain good berry production. Avoid waterlogged soils.

Planting Tips

Plant male and female plants together for berry production — you need at least one male per every 4–6 females. Gender can be difficult to determine in young plants at nurseries; when possible, buy plants that are already sexed, or buy multiple plants from the same seed source and plant a group. Space 6–10 feet apart for a naturalistic planting; 4–6 feet apart for a hedgerow. Fall planting is preferred in most of its range. The plant spreads by root suckers — factor this in when choosing a location.

Pruning & Maintenance

Silver Buffaloberry requires very little pruning under normal conditions. Remove dead or damaged branches in late winter. The thorny branches make pruning physically challenging — use heavy leather gloves and long-sleeved clothing. To control spread, remove root suckers as they appear. The shrub can be rejuvenated by cutting back hard (to 12 inches) in late winter, which stimulates vigorous new growth.

Landscape Uses

- Impenetrable windbreak or security hedge — the formidable thorns deter all but the most determined intruders

- Wildlife garden — the berries support dozens of bird and mammal species

- Erosion control — extensive root system stabilizes slopes and streambanks

- Xeriscape specimen — the silvery foliage is striking in dry gardens

- Nitrogen-fixer — improves soil when planted with other species

- Riparian restoration along Great Plains rivers and coulees

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Silver Buffaloberry is one of the highest-value wildlife plants in the Great Plains and Intermountain West, providing an abundant late-season berry crop at a time when most other fruits are gone.

For Birds

The berry clusters are consumed by American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Bohemian Waxwings, Sharp-tailed Grouse, Greater Sage-Grouse, Ring-necked Pheasants, Gray Catbirds, and many other fruit-eating species. In the Great Plains, Silver Buffaloberry thickets are important migration stopover sites for fall migrants moving south, who time their routes to coincide with the berry crop. The dense, thorny thickets also provide unparalleled nesting cover and escape from predators.

For Mammals

Grizzly Bears and Black Bears rely heavily on Silver Buffaloberry as a pre-hibernation food source across the northern Rockies and Great Plains — it is considered one of the most important bear foods in the ecosystem. Coyotes, foxes, raccoons, and skunks eat the berries. Pronghorn and mule deer browse the twigs and leaves. Small mammals including prairie dogs, ground squirrels, and cottontails use the thickets for shelter.

For Pollinators

While the small flowers are wind-pollinated, Silver Buffaloberry still attracts some early-season native bees and flies seeking pollen. The early bloom (March–May) makes it one of the first pollen sources available for queen bumblebees emerging from hibernation in the Great Plains and Intermountain West.

Ecosystem Role

Silver Buffaloberry’s nitrogen-fixing symbiosis with Frankia bacteria makes it a soil improver — it enriches surrounding soils with fixed nitrogen, benefiting neighboring plants and supporting more productive plant communities. In disturbed or degraded rangelands, it is one of the pioneer species that can establish and begin soil restoration without any fertilizer input. Its dense thickets also trap blowing soil and snow, creating more stable microhabitats for other plants and animals.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Silver Buffaloberry berries were an important food for virtually every Plains Indian nation within its range. The Lakota, Nakoda (Assiniboine), Blackfoot, Crow, Mandan, Hidatsa, and many other groups harvested the berries in large quantities in late summer and fall. The traditional method of harvest — beating fruiting branches over a hide or canvas to knock the berries free — was very efficient and could gather large quantities quickly. The berries were eaten fresh (after frost, when bitterness diminishes), dried for winter storage, or cooked into soups and stews with dried buffalo meat.

The most distinctive traditional use of Silver Buffaloberry was in the preparation of a foamy, meringue-like dessert made by whipping the berries with water — the high saponin content causes the juice to foam when beaten vigorously. This dish, made with the tart berries and sometimes sweetened with dried fruits or berries, was a prized food served at special occasions. The foam is so stable and persistent that the dish was called “Indian ice cream” by early European visitors. This preparation was made across the entire Plains culture area and is still made in some communities today.

Silver Buffaloberry thickets also provided important practical resources: the tough, dense thorny branches were used to make protective barriers around camps and corrals. The wood, though small, is very hard and was used for small tools and implements. Medicinally, preparations from the bark and berries were used to treat stomachaches, constipation, and other ailments. The shrub was also important as a winter windbreak and shelter for both people and livestock.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I need both male and female plants for berries?

Yes — Silver Buffaloberry is dioecious, meaning male and female flowers are on separate plants. You need both to produce berries. Plant at least one male for every 4–6 females. Many nurseries now sell sexed plants; ask specifically for female plants (berry-producers) and males (pollinators). Plants propagated from cuttings of known-sex plants are the most reliable option.

Are Silver Buffaloberry berries edible?

Yes, with preparation. Raw berries are intensely tart and bitter from saponin compounds, but after frost (or cooking) the bitterness diminishes significantly and they become pleasantly tart-sweet. They can be made into jelly, syrup, sauce, wine, or the traditional Indigenous foamy dessert. Do not eat large quantities raw, as the saponins can cause stomach upset.

How do I control Silver Buffaloberry spreading?

Silver Buffaloberry spreads extensively by root suckers and can colonize a wide area over time. To control spread, mow or cut suckers around the margins of the planting regularly. The suckers are difficult to dig out because of the thorny parent plant overhead, so early intervention when suckers are small is key. In small gardens, plant in a large root barrier container buried in the ground.

How cold-hardy is Silver Buffaloberry?

Extremely cold-hardy — it is rated to USDA Zone 2, tolerating temperatures to -50°F (-46°C). It is one of the most cold-tolerant native shrubs in North America and is an excellent choice for gardens in Montana, the Dakotas, Minnesota, and other extremely cold-winter regions.

Why won’t my Silver Buffaloberry fruit?

The most common cause is planting only female (or only male) plants. If you have only one plant or plants of only one sex, no berries will form. A male plant must be present and blooming simultaneously with the female flowers for pollination to occur. Young plants may also take 3–5 years to reach fruiting maturity.