Winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata)

Krascheninnikovia lanata (syn. Ceratoides lanata), commonly called Winterfat, White Sage, or Lambstail, is a remarkable native subshrub that earns its evocative common name from the dense, fluffy white seed heads that blanket the plant through fall and winter — providing critical, high-protein forage for sheep, cattle, elk, deer, and Pronghorn during the harshest months of the year when other plants offer nothing. Native to the vast arid and semi-arid plains, plateaus, and mountain foothills of western North America, Winterfat is one of the most important range plants of the Intermountain West.

This member of the Amaranthaceae (amaranth) family grows as a low, rounded subshrub typically 1 to 3 feet tall, with narrow, woolly-hairy leaves and an intricate woody framework covered in dense white to tawny hairs. The entire plant has a soft, silvery-white to pale gray appearance that catches and reflects winter light beautifully. Winterfat tolerates highly alkaline and even moderately saline soils — a rare and valuable trait that makes it indispensable for revegetating disturbed soils in the alkaline flats and valleys common across the Great Basin, Colorado Plateau, and Wyoming Basin.

Ecologically, Winterfat serves as a foundational species in cold desert shrubland communities across millions of acres. It provides essential winter forage with remarkably high protein content (up to 12–15% crude protein when other plants are dormant), making it a literal “fat” source for wintering livestock and wildlife that have few other options. Its deep root system and tolerance for drought, alkalinity, and cold make it a premier choice for range restoration, erosion control, and low-water native landscaping across the arid West.

Identification

Winterfat grows as a low, branching subshrub with a woody base and annual herbaceous shoots, typically reaching 1 to 3 feet (30–90 cm) in height and somewhat wider in spread. The plant has a rounded, mounded form in open conditions. All parts — stems, leaves, and fruits — are densely covered in long, white woolly hairs that give the entire plant a distinctive pale, fluffy appearance. This woolly covering is the key identifying feature: no other common shrub of the cold desert West looks quite like a Winterfat in full seed.

Leaves

The leaves are narrow and linear to narrowly oblong, 1 to 5 cm long and only 2–6 mm wide — somewhat resembling miniature rosemary leaves in shape. Both surfaces are covered in dense, white woolly hairs, giving them a silvery appearance. The leaf margins are entire (no teeth). Leaves are arranged alternately along the stems, emerging in spring and persisting through summer before the plant’s attention turns to seed production in fall. The aromatic quality is mild compared to true sagebrush, but the plant does have a faint characteristic scent.

Stems & Bark

The basal stems are woody and persistent, gray-brown to tan, with a stringy, fibrous bark. The annual shoots arising from these woody bases are covered in dense white woolly hairs that eventually become tawny to rusty-brown with age. In late winter and early spring, before new growth emerges, the old woolly seed heads give the plant a pale amber to cream color. The entire plant has a soft, pillow-like texture due to the woolly covering — quite distinct from the stiffer, more aromatic sagebrushes it sometimes grows alongside.

Flowers & Fruit

Winterfat blooms from mid-summer through fall, producing small, inconspicuous flowers without petals. Male and female flowers are borne separately on the same plant (monoecious). The female flowers develop into the plant’s most spectacular feature: each fruit is enclosed in two distinctive, woolly bracts covered in long, silky white hairs that give the fruiting clusters their characteristic fluffy, cotton-ball appearance. These “woolly” seed clusters develop from late summer through fall, covering the entire upper portions of the plant in a shaggy white coat that persists through winter and gives the plant its common names. The seeds are consumed by birds, rodents, and — critically — by sheep, cattle, and deer that strip the woolly seed heads from stems during winter foraging.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Krascheninnikovia lanata (syn. Ceratoides lanata) |

| Family | Amaranthaceae (Amaranth / Goosefoot) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous to Semi-Evergreen Subshrub |

| Mature Height | 1–3 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low (Drought Tolerant) |

| Bloom Time | July – September |

| Flower Color | Inconspicuous (fruit covered in showy white woolly bracts) |

| Soil Type | Well-drained; tolerates alkaline and moderately saline soils |

| Soil pH | 7.0–9.0 (alkaline tolerant; needs excellent drainage) |

| Special Features | Critical winter forage; highly drought tolerant; alkaline soil specialist |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

Native Range

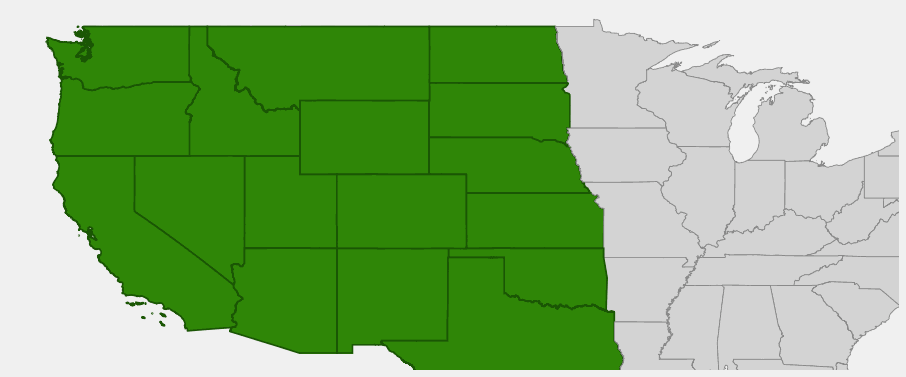

Winterfat is native to a broad sweep of western and central North America, representing one of the most widespread shrub species of North American cold deserts. Its range extends from southern Canada (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba) south through virtually all of the western United States — including Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and the western portions of the Great Plains states (North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas). This extraordinary range reflects Winterfat’s exceptional tolerance for drought, cold, alkalinity, and poor soils.

Winterfat is most abundant and ecologically dominant in the cold desert valleys and plateaus of the Intermountain West, particularly in the Great Basin, Wyoming Basin, Colorado Plateau, and Columbia Basin. Here it forms extensive stands on alkaline flats, bajadas, dry valley floors, and gentle slopes where soils are well-drained and often calcareous or gypsiferous. It is a characteristic species of the “shadscale zone” — the arid lowland vegetation type dominated by shadscale (Atriplex confertifolia) and other salt-tolerant shrubs — as well as the lower margins of sagebrush-steppe communities.

The plant shows remarkable elevation tolerance, growing from near sea level in coastal California to over 11,000 feet in the Rocky Mountains. Its ability to persist in both continental and maritime climates, hot and cold deserts, and a wide range of soil types speaks to the deep adaptive flexibility of this resilient species. In degraded rangeland, Winterfat is often one of the first natives to disappear under overgrazing (livestock consume it eagerly), but it returns readily to well-managed or fenced sites.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Winterfat: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Winterfat is an exceptionally tough, low-maintenance plant that thrives on neglect once established. It requires excellent drainage above all else, and rewards the grower with beautiful silvery foliage and the spectacular woolly white seed display that earns it its common name. Its tolerance for alkaline soils and extreme drought makes it one of the most useful native plants for challenging dry western landscapes.

Light

Winterfat demands full sun. It evolved in the open, treeless cold deserts and high plains of the West and will not thrive in partial shade. Site it in the most exposed, open areas of the garden — south or west-facing slopes are ideal. In full sun with excellent drainage, Winterfat achieves its most compact, attractive form and develops the most vivid white woolly seed heads. In shade, it becomes weak, open-branched, and far less ornamental.

Soil & Water

Drainage is the non-negotiable requirement for Winterfat. It grows in soils ranging from sandy to clay loam, gravel, and rocky slopes — but whatever the texture, the soil must drain freely after rain or irrigation. Winterfat is absolutely intolerant of wet feet or consistently moist soils; poor drainage will kill it within one or two seasons. Its most prized soil characteristic, however, is tolerance for alkalinity: it grows in soils with pH up to 9.0 and even tolerates moderate salinity — conditions that exclude nearly all other ornamental plants. Once established (after the first full growing season), Winterfat requires no supplemental irrigation in most of its native range. During establishment, water once every 1–2 weeks in summer; thereafter, rainfall alone is sufficient in areas receiving 8+ inches annually.

Planting Tips

Plant Winterfat in spring from container stock or direct-seed in fall (seeds require cold stratification naturally provided by winter). Improve drainage in heavy clay soils by raising beds or adding gravel. Avoid rich, amended soils — Winterfat is adapted to poor soils and excess fertility promotes lush, weak growth prone to flopping. Space plants 3–4 feet apart for a naturalistic planting; they will spread slowly to fill gaps. In restoration settings, Winterfat can be seeded at 0.5–1 lb/acre using a rangeland drill seeder or broadcast seeding on freshly scarified soil in fall.

Pruning & Maintenance

Winterfat benefits from a light annual cutback to prevent the plant from becoming too woody and open. In late winter or very early spring (before new growth), cut the plant back by one-third to one-half to stimulate vigorous new shoots and maintain a compact, attractive form. Avoid pruning in late summer or fall — the woolly seed display is the plant’s greatest seasonal ornamental asset and should be left intact through winter for wildlife and visual interest. Winterfat has no significant pest or disease issues in well-drained sites. Overwatering and poor drainage are the primary causes of failure.

Landscape Uses

Winterfat is a versatile plant for dry western gardens and restoration projects:

- Xeriscape planting — exceptional drought tolerance; beautiful year-round interest

- Alkaline soil specialist — one of few ornamental natives thriving in high-pH soils

- Winter wildlife planting — woolly seed heads provide critical forage for deer, birds, and livestock

- Erosion control on dry slopes and disturbed alkaline sites

- Range restoration — essential species for restoring degraded cold desert rangelands

- Low border or mass planting — silvery foliage and white seed heads create striking seasonal display

- Rock garden — excellent in gravelly, well-drained rock garden settings

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Winterfat’s common name says it all: this is a plant that keeps wildlife alive through winter. Its nutritional value as a winter forage plant is exceptional, and it plays an outsized ecological role relative to its modest size.

For Birds

The woolly seed heads of Winterfat are consumed by numerous bird species during fall and winter. Horned Larks and Longspurs are particularly associated with Winterfat-dominated flats, feeding heavily on the seeds. Sage Sparrows (now Sagebrush Sparrows) and Brewer’s Sparrows use Winterfat shrubs for nesting cover in mixed shrubland communities. Greater Sage-Grouse feed on Winterfat leaves in early spring, when the fresh growth provides a high-protein supplement after winter. The plant’s low, mounded form provides cover for ground-nesting birds and ground-foraging sparrows, larks, and pipits throughout the year.

For Mammals

Winterfat is perhaps the most critical winter forage plant for large mammals across the cold desert West. Pronghorn consume it heavily when snow covers grasses, relying on the woolly seeds and foliage for sustenance. Mule Deer and Elk browse Winterfat through fall and winter, particularly valuing it for its high crude protein content (up to 15%) when other forage is dormant or buried. Historically, Bighorn Sheep depended heavily on Winterfat in winter range areas of the Great Basin. Domestic sheep and cattle use it similarly, which is why Winterfat was so heavily grazed and reduced across much of the West during the 19th and 20th centuries.

For Pollinators

While Winterfat’s small, inconspicuous flowers are wind-pollinated, the plant plays an indirect role in pollinator support. As a foundational species in cold desert shrublands, Winterfat’s presence helps structure the plant community that includes associated wildflowers and forbs — penstemon, milkvetch, buckwheat — that are primary nectar sources for native bees and butterflies in these arid landscapes. The deep-rooted Winterfat also helps maintain soil moisture and organic matter that supports the broader plant community.

Ecosystem Role

Winterfat serves multiple ecosystem functions in cold desert and semi-arid grassland communities. Its deep root system (roots can extend 6 feet or more) accesses deep soil moisture and helps stabilize soils against wind and water erosion — critical in the bare, wind-swept alkaline flats where it often grows. The woolly seed heads catch windblown soil and sand, building microhabitat mounds around the plant base that increase local soil organic matter and moisture retention. Winterfat’s high palatability and nutritional value make it a critical food source when other plants fail — it is a “staff of life” species for the cold desert ecosystem.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Winterfat has been recognized and used by Indigenous peoples of western North America for thousands of years. For the Navajo, Hopi, and Pueblo peoples of the Southwest, Winterfat — known as “white sage” in some communities — held both practical and ceremonial significance. The woolly leaves and stems were used to create soft padding for cradle boards, and the plant’s dense, white appearance made it a natural choice for ceremonial contexts requiring symbols of purity or winter.

Medicinally, numerous western nations used Winterfat to treat a range of conditions. The Shoshone and Paiute prepared infusions from the leaves to treat fevers and as an eyewash. The plant’s high mineral content and protein-rich foliage made it a famine food in some traditions — the seeds could be ground and mixed with other foods during lean winter periods. The Cheyenne and Arapaho used Winterfat smoke in purification ceremonies, viewing its distinctive woolly appearance as spiritually significant.

For early Euro-American settlers and ranchers, Winterfat was simply invaluable — a discovery that dramatically expanded the range of viable winter range for sheep and cattle across the alkaline flats and cold deserts of the West. Ranchers who understood Winterfat’s value protected it carefully; those who did not often overstocked to the point of eliminating it, leaving degraded range dominated by invasive annual grasses. Today, Winterfat is widely recognized by range managers and restoration ecologists as a keystone species for cold desert revegetation. The USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service includes it in standard seed mixes for Great Basin and Colorado Plateau restoration, and its seeds are commercially available from specialty native plant seed suppliers throughout the West.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Winterfat the same as White Sage?

No — “White Sage” is a confusing common name applied to multiple unrelated plants. True White Sage (Salvia apiana) is a California native in the mint family with broad gray-white leaves and a strong aromatic smell. Winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata) is in the amaranth family, has narrow woolly leaves, and is native to the cold desert West rather than coastal California. Both have silvery-white appearances and are used in ceremony by Indigenous peoples, but they are botanically unrelated and quite different plants.

Why is it called Winterfat?

The common name “Winterfat” comes from the plant’s value as a high-protein, nutritious winter forage source for livestock and wildlife. The “fat” in the name refers to the fattening, nutritious quality of the plant — animals that browse Winterfat through the cold months maintain body condition (their “fat”) better than those without access to it. The woolly white seed heads also have a fat, fluffy appearance that may contribute to the name.

Can I grow Winterfat in clay soil?

Winterfat can grow in clay soil only if drainage is excellent. Heavy, poorly drained clay will cause root rot and kill the plant within a season or two. If you have clay soil and want to grow Winterfat, raise the planting area by 6–12 inches and incorporate coarse gravel to improve drainage, or plant on a slope where water naturally moves away from the root zone. Well-drained sandy or gravelly clay soils are acceptable.

Does Winterfat need watering once established?

In most of its native range (receiving 8–15 inches of annual precipitation), established Winterfat requires no supplemental irrigation. In its first growing season, water every 1–2 weeks to help roots establish. After that, rainfall alone is typically sufficient. Overwatering is more dangerous than underwatering for this species — too much moisture promotes root rot and plant death.

Is Winterfat good for pollinators?

Winterfat itself is wind-pollinated and not a primary nectar or pollen source for bees and butterflies. However, it is an important structural species in plant communities that do support pollinators — and its early-summer blooming period contributes some pollen to the general ecosystem. For a pollinator-focused planting in arid western gardens, pair Winterfat with native penstemon, buckwheat (Eriogonum), or desert marigold for a complete habitat planting.