Black Willow (Salix nigra)

Salix nigra, the Black Willow, is the largest and most commercially valuable willow native to North America, and one of the most ecologically essential trees of riparian zones from New England to the Gulf Coast. Named for the dark, rough-furrowed bark that distinguishes mature specimens, this fast-growing deciduous tree can tower over 100 feet in favorable conditions along rivers, streams, and lake shores. It is the quintessential streamside tree of the eastern United States — a pioneer species that stabilizes banks, filters runoff, and provides structure for entire aquatic and riparian ecosystems.

Black Willow is far more than a utilitarian bank-stabilizer. It is a keystone species for insects, supporting over 450 species of caterpillars and larvae — making it one of the most ecologically productive native trees in North America after oaks. Its dense, arching canopy provides shade that keeps stream water cool for fish, while its roots bind streambanks with a tenacity that no engineered solution has ever matched. The tree leafs out early in spring and holds its leaves late into autumn, extending its ecological contributions through much of the year.

For gardeners and restoration practitioners in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, Black Willow offers unmatched performance in wet and seasonally flooded sites where few other trees can establish. It transplants easily, grows with extraordinary speed, and — crucially — hosts butterflies and moths in massive numbers, including the Viceroy butterfly, making it a critical component of any wildlife garden designed to support native pollinators and birds.

Identification

Black Willow is typically found as a large tree with a short, leaning trunk and an open, irregularly branching crown. In optimal conditions along major rivers, specimens can exceed 100 feet in height with trunk diameters approaching 3–4 feet. More commonly, trees reach 40–70 feet tall in the wild, with a broad, spreading crown of whiplike branches.

Bark

The bark is the most distinctive identification feature — dark brown to nearly black on mature trees, deeply divided into interlacing, scaly ridges that give the trunk a rough, shaggy appearance. Young trees and branches have yellowish-brown to reddish-brown, flexible bark. The characteristic dark, furrowed bark of older specimens gives the species both its common and scientific names (nigra = black). The inner bark contains salicin, a compound related to aspirin that has been used medicinally for centuries.

Leaves

The leaves are narrow and lance-shaped (lanceolate), 3 to 6 inches long and only ½ to ¾ inch wide, tapering to a long, curved tip. The upper surface is shiny, bright green; the underside is pale green. Fine, incurved teeth line the leaf margins. The foliage emerges early in spring — often among the first trees to leaf out — and stays green into late autumn, turning yellow before dropping. The long, narrow leaves rustle and shimmer in the slightest breeze, giving the tree its characteristic graceful, flowing appearance.

Flowers & Fruit

Black Willow is dioecious — male and female flowers grow on separate trees. The flowers appear in early spring as catkins (pussy willows), emerging with or just before the leaves. Male catkins are yellow and produce pollen; female catkins are greenish. The tiny fruit capsules split in late spring to release masses of cottony seeds that drift on the wind. The wood is soft, lightweight, and flexible — historically used for artificial limbs, boxes, and charcoal for gunpowder. Its roots are aggressively spreading and can clog drainage pipes if planted too close to infrastructure.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Salix nigra |

| Family | Salicaceae (Willow) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 50+ ft (commonly 40–100 ft) |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Bloom Time | March – May |

| Flower Color | Yellow (male catkins), Green (female catkins) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–9 |

Native Range

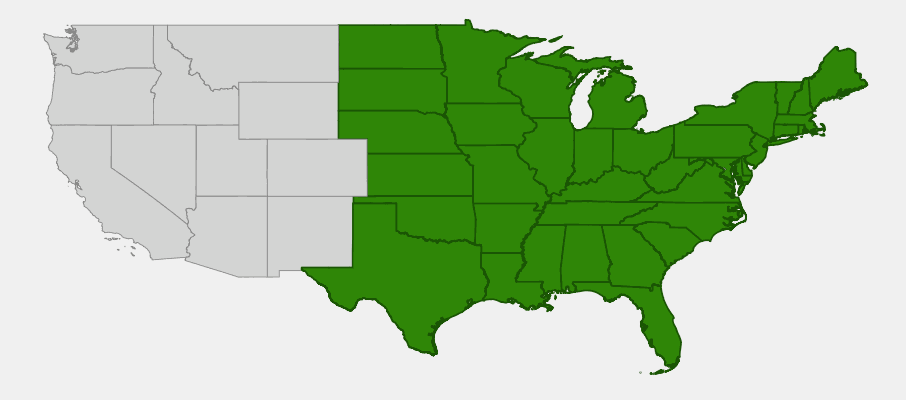

Black Willow has one of the broadest natural ranges of any native North American tree, occurring from New Brunswick and Maine south along the Atlantic coast to Florida, and west to Nebraska and Texas — encompassing nearly the entire eastern half of the United States. In the Northeast, it is a common and conspicuous feature of river corridors, where it often forms dense stands along actively migrating streambanks.

In New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, Black Willow is found along virtually every major river system — the Hudson, Delaware, Susquehanna, Mohawk, and their countless tributaries. It thrives in floodplain zones, oxbow lakes, marshes, and anywhere that soil remains moist to wet for much of the year. Elevation range extends from sea level to about 3,000 feet in the Appalachians.

The tree’s aggressive root system makes it a natural pioneer on disturbed streambanks and floodplains. It rapidly colonizes bare sand and gravel bars after floods, producing the first woody cover that stabilizes soils and allows other species to establish. In riparian forest succession, Black Willow is often the founding species around which the full richness of floodplain forest develops over decades.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Black Willow: New York, Pennsylvania & New Jersey

Growing & Care Guide

Black Willow is one of the easiest native trees to establish in moist to wet sites, and one of the fastest-growing trees in North America. Once planted near water, it virtually takes care of itself — growing several feet per year in favorable conditions.

Light

Black Willow thrives in full sun, which promotes maximum growth and the densest, healthiest crown. It also tolerates part shade, particularly in riparian corridors where it may be shaded for portions of the day by taller trees. Full sun on moist to wet soil is the ideal combination. Avoid deep shade, which will cause spindly, weak growth.

Soil & Water

This tree is extraordinarily tolerant of wet, saturated, and even temporarily flooded soils — conditions that would kill most other trees. It thrives in clay, loam, or sandy soils as long as moisture is consistently available. Plant at the water’s edge, in rain gardens, bioswales, along stream corridors, and in seasonally flooded areas. While it prefers consistent moisture, established trees show moderate drought tolerance once roots reach the water table. Avoid permanently arid upland sites.

Planting Tips

Black Willow is uniquely easy to propagate. Live stakes — cuttings 12–24 inches long, 1–2 inches in diameter, pushed 6–12 inches into moist soil — root readily with near-100% success in spring. This makes it one of the most cost-effective plants for large-scale streambank restoration. Container-grown trees can be planted any time during the growing season if watered adequately. Plant at least 30–50 feet from foundations, septic systems, and water lines, as roots aggressively seek and enter pipes.

Pruning & Maintenance

Black Willow requires minimal pruning. Remove any dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter. The tree coppices readily — if cut near the ground, it will resprout vigorously from the stump, making it useful for biomass production or to periodically renew old plantings. Willows are generally short-lived compared to oaks and maples (often 30–50 years), but they reseed and resprout so readily that colonies can persist indefinitely through vegetative regeneration.

Landscape Uses

- Streambank stabilization — one of the most effective native species for erosion control

- Riparian buffer strips along rivers, streams, and drainage channels

- Bioswales and rain gardens in stormwater management systems

- Wildlife habitat — critical for butterflies, moths, and migratory birds

- Floodplain restoration as a founding pioneer species

- Pond and lake shores where its weeping form provides visual interest

- Wet woodland gardens where few other trees can grow

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Black Willow is among the most ecologically productive native trees in the eastern United States. Its contributions to wildlife span from insects to large mammals, across every season of the year.

For Birds

The enormous caterpillar diversity supported by Black Willow makes it a critical food source for nesting songbirds, which depend on soft-bodied insects to feed their nestlings. Warbling Vireos, Yellow Warblers, and Willow Flycatchers are among the species that commonly nest in or near Black Willow stands. The dense branching provides excellent nesting cover, and the cottony seeds are used by American Goldfinches and other small birds as nesting material. In winter, the buds provide food for tree sparrows, American Tree Sparrows, and other overwintering birds.

For Mammals

Beavers prize Black Willow above almost all other trees, using both the wood for dam construction and the bark and foliage for food. Muskrats also consume the bark and roots. White-tailed Deer browse the foliage, and elk use the dense willow stands for thermal cover in winter. The aggressive resprouting ability of willow after heavy browsing or beaver cutting makes it naturally resilient to mammal pressure — an ecological relationship refined over millennia.

For Pollinators

Black Willow is one of the earliest-blooming native trees, producing pollen-rich catkins when few other food sources are available in early spring. Native bees — including mining bees (Andrena spp.), mason bees (Osmia spp.), and bumblebee queens emerging from winter dormancy — depend heavily on willow pollen as an essential early-season protein source. The tree supports over 450 species of Lepidoptera (caterpillars and moths), making it second only to oaks among North American woody plants in insect-hosting capacity.

Ecosystem Role

Beyond food, Black Willow shapes the physical structure of riparian ecosystems. Its roots hold streambanks against erosion, reducing turbidity and improving water quality downstream. The shading it provides keeps stream temperatures cool, which is critical for cold-water fish like trout. Fallen willow branches and leaf litter enter the aquatic food web as habitat and food for aquatic invertebrates. The tree is a keystone riparian species — remove it and the entire web of organisms that depend on it shifts dramatically.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Willows hold a rich place in human history across every culture where they grow. Black Willow’s bark — like that of all willows — contains salicin, the compound from which aspirin was derived. Indigenous peoples throughout eastern North America used willow bark tea to reduce fever and relieve pain, a use documented among the Cherokee, Iroquois, Ojibwe, and many other nations long before European contact. The discovery of this chemical property in the 19th century ultimately led to the synthesis of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) in 1897, one of the most consequential developments in medical history.

Economically, Black Willow was once extensively harvested for its wood, which — though soft and weak — has unique properties that made it valuable for specific applications. It was the preferred wood for artificial limbs, shoe lasts, and toys because it does not splinter easily when cut or struck. Black Willow charcoal was a key ingredient in gunpowder production. The wood was also used extensively for boxes, packing material, doors, and pulpwood for paper production. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, willow wicker was a major commercial product for baskets and furniture.

In more recent decades, Black Willow has gained recognition as one of the most effective native plants for phytoremediation — the use of plants to absorb and process environmental contaminants. Research has shown that willow roots can absorb heavy metals, petroleum products, and other pollutants from contaminated soil and groundwater, making them valuable in bioremediation projects near industrial sites. The tree’s exceptionally fast growth also makes it attractive for biomass energy production, where willows are grown in short-rotation coppice plantations and harvested for bioenergy every 3–5 years.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will Black Willow roots damage my pipes or foundation?

Yes — willow roots are aggressive and will seek out any moisture source, including pipes, septic systems, and foundation cracks. Plant Black Willow at least 30–50 feet from any infrastructure. Near streams, wetlands, or rain gardens far from buildings, the roots pose no concern.

How fast does Black Willow grow?

Very fast — typically 4–8 feet per year in optimal conditions (moist to wet soil, full sun). It is among the fastest-growing native trees in the eastern United States, making it excellent for quick habitat establishment and bank stabilization.

Can I grow Black Willow from cuttings?

Yes, easily. Push 12–24 inch cuttings (pencil-thick to thumb-thick) into moist soil in early spring. They root with nearly 100% success. This makes Black Willow one of the most cost-effective plants for large-scale riparian restoration projects.

Is Black Willow good for butterflies?

Absolutely. Black Willow is a host plant for the Viceroy butterfly, the Mourning Cloak, and over 450 other Lepidoptera species. If you are designing a butterfly garden or wildlife habitat garden near a wet area, Black Willow is one of the highest-value plants you can include.

How long does Black Willow live?

Individual trunks typically live 20–50 years, shorter than most trees. However, the root system survives and resprouts vigorously after the main trunk dies or is removed. Willow colonies can persist in a location for centuries through continuous vegetative regeneration, even as individual stems come and go.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Black Willow?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: New York · Pennsylvania