Box Elder (Acer negundo)

Acer negundo, commonly known as Box Elder, Ash-leaved Maple, or Manitoba Maple, is a fast-growing native deciduous tree that stands out among North American maples for its unique compound leaves and remarkable adaptability to diverse growing conditions. This member of the Aceraceae (maple) family is the only maple species in North America with pinnately compound leaves, making it instantly recognizable even when not in fruit. Despite being widely distributed and ecologically important, Box Elder is often underappreciated due to its weedy reputation and tendency to spread aggressively in disturbed areas.

Growing naturally throughout much of North America from southern Canada to central Mexico, Box Elder typically reaches 30 to 75 feet tall with a broad, irregular crown and often multiple trunks. The species shows remarkable ecological flexibility, thriving in everything from floodplains and streambanks to urban vacant lots and prairie edges. Its compound leaves, bright green winged seeds (samaras), and distinctive bark pattern make it one of the most recognizable trees in its range, while its rapid growth and ability to colonize disturbed sites make it both ecologically valuable and sometimes problematic in managed landscapes.

While Box Elder can spread quickly and may be considered weedy in some contexts, it provides important ecological services including erosion control, wildlife habitat, and rapid revegetation of disturbed areas. The tree is particularly valuable for wildlife, with its seeds feeding numerous bird species and its fast growth providing quick shade and shelter. In appropriate settings — especially naturalistic landscapes, riparian buffers, and large-scale restoration projects — Box Elder’s adaptability and wildlife value make it a useful native tree, though careful consideration should be given to its placement due to its aggressive spreading tendency.

Identification

Box Elder typically grows as a medium-sized deciduous tree reaching 30 to 75 feet (9–23 m) tall with a trunk diameter of 2 to 4 feet (0.6–1.2 m). The growth form is highly variable, ranging from a single-trunked tree with an irregular, broad crown to a multi-stemmed large shrub. In open areas, it often develops a short trunk and wide-spreading branches, while in forest settings it may grow taller and more upright. The overall form is usually somewhat scraggly and irregular, lacking the symmetrical shape of many other maples.

Bark

The bark varies significantly with age and growing conditions. On young trees and branches, the bark is smooth and light gray to greenish-gray. As trees mature, the bark develops shallow furrows and becomes gray to brown with interlacing ridges. Very old trees may have deeply furrowed bark similar to ash trees. The bark on branches often remains smooth longer than on the main trunk, and young twigs may have a purplish or reddish tinge, especially in winter.

Leaves

The leaves are the tree’s most distinctive feature — they are pinnately compound with 3 to 7 leaflets (most commonly 3–5), making Box Elder unique among North American maples. Each leaflet is 2 to 4 inches (5–10 cm) long, oval to lance-shaped, with coarse teeth along the margins. The terminal leaflet is typically the largest and may be three-lobed. The leaves are bright green above and paler beneath, turning yellow (rarely orange) in fall before dropping. The leaf stems (petioles) are often reddish, particularly on young growth.

Flowers

Box Elder is dioecious, meaning individual trees are either male or female. The flowers appear in early spring before the leaves emerge, hanging in drooping clusters (racemes). Male flowers are small, greenish-yellow, and appear in dense hanging clusters 2 to 4 inches long. Female flowers are smaller and appear in loose, drooping clusters. Both types of flowers lack petals and are wind-pollinated, making them relatively inconspicuous compared to many other flowering trees.

Fruit

The fruit consists of paired winged seeds called samaras, typical of all maple species. Box Elder samaras are V-shaped, with each wing 1 to 2 inches (2.5–5 cm) long. They mature in late summer to early fall and are initially green, turning tan or brown as they ripen. The wings are prominently veined and help the seeds helicopter away from the parent tree when they fall. Female trees can produce abundant crops of seeds, which contribute to the species’ reputation for aggressive colonization of disturbed areas.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Acer negundo |

| Family | Aceraceae (Maple) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 30–75 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | High |

| Bloom Time | March – April |

| Flower Color | Greenish-yellow |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–10 |

Native Range

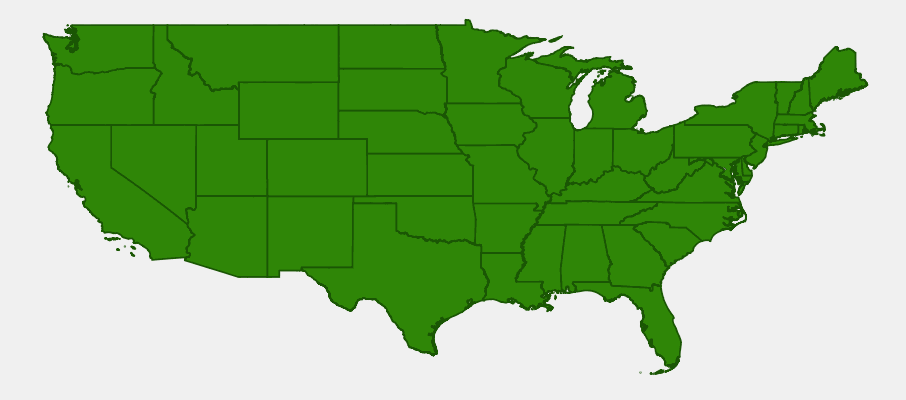

Box Elder has one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American tree, stretching from southern Canada to central Mexico and from coast to coast across the United States. This remarkable distribution reflects the species’ extraordinary adaptability to diverse climatic conditions, soil types, and elevations. The tree is most common and reaches its largest sizes in the central portions of its range, particularly throughout the Great Plains and the Mississippi River valley system.

In its natural habitat, Box Elder is typically found along streams, rivers, floodplains, and other areas with access to groundwater. It’s a pioneer species that quickly colonizes disturbed areas, abandoned fields, and forest edges. The species shows remarkable tolerance for environmental extremes, surviving both severe drought and periodic flooding, temperatures from -40°F to over 100°F, and elevations from sea level to over 6,000 feet. This adaptability has made it both ecologically valuable and sometimes problematic, as it can spread aggressively into areas where it competes with other native vegetation.

Throughout its range, Box Elder serves important ecological functions as a riparian forest species, providing erosion control along waterways and creating habitat for wildlife. However, its rapid growth and prolific seed production have also led to its classification as a nuisance species in some regions, particularly in the western United States where it can invade and dominate riparian areas. Despite this complexity, Box Elder remains an important component of many North American ecosystems and continues to play significant ecological roles across its vast native range.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Box Elder: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Box Elder is one of the easiest native trees to grow, though its aggressive nature requires careful consideration of placement and management. Its rapid growth rate, tolerance of poor conditions, and ability to thrive with minimal care make it useful in specific situations, but its tendency to spread and potential for becoming weedy mean it’s not suitable for all landscape applications.

Light

Box Elder performs best in full sun, where it develops its strongest growth and most typical form. The tree tolerates partial shade but may become more sprawling and less dense in shadier locations. In full sun, Box Elder grows rapidly and maintains better structural integrity, though it will still require regular pruning to maintain an acceptable form in most landscape situations.

Soil & Water

This remarkably adaptable tree grows in virtually any soil type, from rich bottomland soils to poor, rocky, or sandy conditions. Box Elder tolerates both very wet and drought conditions, though it prefers consistently moist soil and grows fastest with regular water access. It’s particularly well-suited to areas with seasonal flooding or high water tables. The tree also tolerates salt, urban pollution, and other challenging environmental conditions that defeat many other species.

Planting Tips

Box Elder is typically planted from seed, as it germinates readily and grows quickly. Seeds can be sown directly in fall or stratified and planted in spring. Container plants establish easily when planted in spring or early fall. Choose the planting location carefully, as Box Elder can spread aggressively through root sprouts and abundant seedlings. Plant at least 30-50 feet from buildings and other trees to account for its ultimate size and spreading tendency.

Pruning & Maintenance

Regular pruning is essential for Box Elder to maintain an acceptable form and prevent structural problems. The fast growth often results in weak branch attachments and multiple leaders that require corrective pruning when young. Remove suckers and unwanted seedlings promptly to prevent spread. Prune during dormant season to maintain shape and remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches. Be prepared for ongoing maintenance, as Box Elder requires more regular attention than many other native trees.

Landscape Uses

Box Elder is best suited for specific landscape applications where its aggressive nature is not problematic:

- Riparian restoration — excellent for streambank stabilization and erosion control

- Large-scale naturalistic plantings — where spreading is acceptable or desired

- Temporary plantings — quick shade while slower-growing species establish

- Wildlife habitat areas — provides food and nesting sites for numerous species

- Difficult sites — tolerates conditions that challenge other trees

- Windbreaks — rapid growth provides quick wind protection

- Reclamation projects — helps stabilize and revegetate disturbed areas

Considerations

Before planting Box Elder, consider its aggressive spreading habit, relatively short lifespan (50–75 years), susceptibility to storm damage, and attraction to boxelder bugs. The tree is not recommended for small properties, formal landscapes, or areas where controlled growth is important. Female trees produce abundant seeds that can create maintenance issues, so male trees may be preferable in some situations.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Despite its weedy reputation, Box Elder provides significant wildlife value and plays important ecological roles throughout its range. Its rapid growth, abundant seeds, and ability to colonize disturbed areas make it a valuable pioneer species that supports diverse wildlife communities.

For Birds

Box Elder seeds are consumed by numerous bird species, including Evening Grosbeaks (which may take their scientific name Coccothraustes vespertinus partly from their association with box elder seeds), Cardinals, House Finches, and various sparrow species. The tree provides nesting sites for many birds, including woodpeckers who excavate holes in the soft wood, and cavity-nesting species who use these abandoned holes. The irregular growth form creates dense branching that offers good nesting habitat and cover for smaller songbirds.

For Mammals

Small mammals including squirrels, chipmunks, and mice consume Box Elder seeds and use the tree for shelter and nesting. Beavers occasionally use Box Elder for dam construction and food, particularly young saplings and branches. Deer may browse young shoots and leaves, though the tree is not a preferred food source. The tree’s ability to sprout from damaged trunks makes it somewhat resilient to mammal damage.

For Insects

Box Elder is host to numerous insect species, most notably the boxelder bug (Boisea trivittata), which feeds on the seeds and can become a household pest when it seeks overwintering sites. The tree also supports various moth and butterfly larvae, including the Cecropia moth and other native Lepidoptera. Many beneficial insects use the flowers for nectar in early spring when few other flowers are available.

Ecosystem Role

As a pioneer species, Box Elder plays crucial roles in ecological succession and habitat development. It quickly colonizes disturbed areas, stabilizes soil with its extensive root system, and creates conditions that allow other plant species to establish. In riparian areas, Box Elder provides important erosion control and helps maintain streambank stability. The tree’s ability to grow in challenging conditions makes it valuable for revegetating damaged ecosystems and providing habitat structure while slower-growing species become established.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Box Elder has a long history of use by Indigenous peoples of North America, who found various applications for different parts of the tree. Many Plains tribes, including the Dakota, Lakota, and Omaha, tapped Box Elder trees in early spring to collect sap, which was boiled down to make a syrup similar to maple syrup, though generally less sweet and in smaller quantities than from sugar maples. This practice provided an important early-season source of carbohydrates and was particularly valuable on the Great Plains where sugar maples were not available.

The wood of Box Elder, while soft and not particularly durable, was used by Indigenous peoples for various purposes including making bowls, containers, and temporary structures. The inner bark was sometimes used for cordage and basketry, while the leaves and bark had medicinal applications in some tribal traditions. Some groups used preparations from Box Elder to treat eye problems, skin conditions, and digestive issues, though these uses varied significantly among different cultural groups.

European settlers adopted some Indigenous uses of Box Elder and found additional applications for the tree. The wood was used for making cheap furniture, boxes (hence the name “box elder”), and paper pulp. Despite its reputation for being a “trash tree,” Box Elder wood has some positive qualities — it’s easy to work, takes stain well, and the figured wood from mature trees can be quite attractive. Some woodworkers prize burled or figured Box Elder for turned items and small decorative objects.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Box Elder was sometimes planted as a street tree and windbreak, particularly on the Great Plains where few other trees could survive the harsh conditions. However, its tendency to break in storms, produce abundant seeds, and create maintenance problems led to it falling out of favor for urban use. Today, Box Elder is primarily valued for ecological restoration and wildlife habitat rather than ornamental or commercial purposes, though it continues to serve important roles in riparian forest management and erosion control projects.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Box Elder really a maple?

Yes, despite its compound leaves that look nothing like typical maple leaves, Box Elder is indeed a true maple (genus Acer). It’s the only North American maple with compound leaves, but its winged seeds (samaras) and other characteristics clearly identify it as a member of the maple family. It’s sometimes called “ash-leaved maple” because of the leaf similarity to ash trees.

Should I plant Box Elder in my yard?

Box Elder is generally not recommended for small residential properties due to its aggressive spreading habit, relatively short lifespan, and tendency to create maintenance problems. It’s better suited to large properties, naturalistic areas, or specific applications like erosion control where its rapid growth and spreading are advantageous rather than problematic.

Why do I have so many Box Elder seedlings in my yard?

Box Elder produces abundant winged seeds that are easily dispersed by wind. If there are female Box Elder trees in your area, you may see numerous seedlings appearing each year. These are easy to remove when small but can quickly establish if left unmanaged. The best control is to remove seedlings promptly and consider removing nearby female trees if possible.

Are boxelder bugs harmful?

Boxelder bugs are primarily a nuisance rather than a serious pest. They feed on Box Elder seeds and don’t damage other plants or harm humans, but they can become household pests when they seek warm places to overwinter. The bugs are most numerous around female Box Elder trees, so removing these trees can reduce local populations.

How can I tell male from female Box Elder trees?

Male and female Box Elder trees can only be reliably distinguished when flowering or fruiting. Male trees produce drooping clusters of yellowish flowers but no seeds. Female trees produce the winged seeds (samaras) and typically have smaller, less conspicuous flowers. Many people prefer male trees in landscape settings since they don’t produce the abundant seeds that can create maintenance issues.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Box Elder?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota