Cascara (Rhamnus purshiana)

Rhamnus purshiana (syn. Frangula purshiana), commonly known as Cascara, Cascara Sagrada, or Chittem Bark, is a distinctive native deciduous tree of the Pacific Northwest that holds an extraordinary place in both ecology and human history. This member of the Rhamnaceae (buckthorn) family earned its Spanish name — cascara sagrada, meaning “sacred bark” — because its dried bark was the most widely used natural laxative in North America for over a century. The Chinook Jargon name, “chittem stick,” reflects its deep significance to Indigenous peoples of the region long before European contact.

Growing naturally in the moist understory of mixed deciduous-coniferous forests, Cascara is a graceful small tree reaching 15 to 40 feet tall, with smooth silver-gray bark that develops distinctive light splotching from lichens over time. Its large, prominently veined oval leaves, tiny greenish-yellow flowers, and clusters of dark purple-black berries make it both ecologically valuable and visually appealing in the landscape. The berries alone feed over 40 species of birds, while the dense, brushy growth provides essential thermal cover and hiding places for wildlife.

Despite its historical over-harvesting for the bark trade — which significantly reduced wild populations during the 1900s — Cascara remains an excellent choice for restoration projects, wildlife gardens, and sustainable native landscaping throughout the Pacific Northwest. Its shade tolerance, adaptability to moist soils, and exceptional wildlife value make it a cornerstone species for anyone building a native plant garden in Oregon or Washington.

Identification

Cascara typically grows as a large shrub or small tree, reaching 15 to 39 feet (4.5–12 m) tall with a trunk 8 to 20 inches (20–50 cm) in diameter. The growth form varies from a single-trunked tree to a multi-stemmed large shrub, depending on growing conditions and light availability. One of its most distinctive features is its buds without scales — unique among trees of the Pacific Northwest region.

Bark

The bark is perhaps Cascara’s most notable feature — it is thin, smooth, and brownish to silver-gray in color, often decorated with light splotches from lichens that give it a mottled, attractive appearance. The inner bark is smooth and yellowish when freshly cut, turning dark brown with age or exposure to sunlight. This inner bark contains the bitter compounds that made Cascara famous in medicine. The bark has an intensely bitter flavor that can remain in the mouth for hours, overpowering and even numbing the taste buds — a characteristic that has also been used to discourage nail-biting by applying it to fingernails.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, deciduous, and arranged alternately, often clustered near the ends of twigs on reddish young stems. Each leaf is oval, 2 to 6 inches (5–15 cm) long and ¾ to 2 inches (2–5 cm) wide, with a prominent midrib and 10 to 12 pairs of parallel, pinnate veins that give the leaf a distinctly ribbed texture. The upper surface is shiny and dark green; the underside is a dull, paler green. Leaf margins have tiny, fine teeth. In autumn, the foliage turns a warm yellow before dropping.

Flowers & Fruit

The flowers are tiny — just ⅛ to ¼ inch (3–5 mm) in diameter — with five greenish-yellow petals forming a small cup shape. They bloom in umbel-shaped clusters emerging from leaf axils on distinctive stalks (peduncles). The flowering season is brief, from early to mid-spring, disappearing by early summer. Despite their small size, the flowers attract a variety of pollinators including native bees and beneficial insects.

The fruit is a small drupe, ¼ to ⅜ inch (6–10 mm) in diameter, that ripens in a beautiful progression: bright red at first, quickly maturing to deep purple or black. Inside is a yellow pulp surrounding two or three hard, smooth, olive-green to black seeds. The berries ripen from late summer through early fall and are eagerly consumed by birds and mammals, who distribute the indigestible seeds throughout the forest.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Rhamnus purshiana (syn. Frangula purshiana) |

| Family | Rhamnaceae (Buckthorn) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree / Large Shrub |

| Mature Height | 30 ft |

| Trunk Diameter | 8–20 in (20–50 cm) |

| Growth Rate | Moderate |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Soil Type | Moist, well-drained; loamy or sandy |

| Soil pH | 5.5–7.0 (slightly acidic to neutral) |

| Bloom Time | April – June |

| Flower Color | Greenish-yellow |

| Fall Color | Yellow |

| Fruit | Red to purple-black drupes (berries) |

| Deer Resistant | No (mule deer and elk browse foliage) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 6–9 |

Native Range

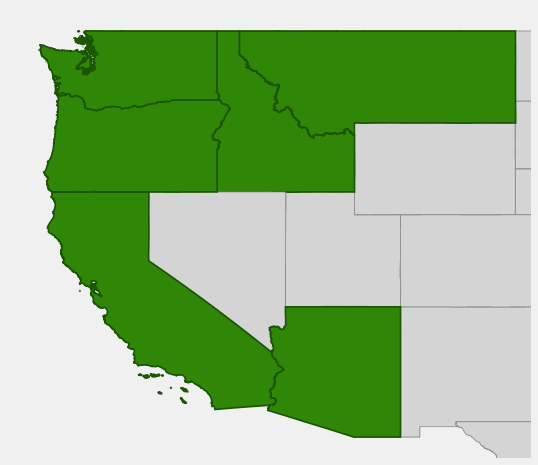

Cascara is native to western North America, ranging from southern British Columbia south through western Washington and Oregon to central California, and eastward to northwestern Montana. The species is most common in the moist valleys and lower mountain slopes west of the Cascade Range, but extends into the northern Rocky Mountains where suitable moist habitats exist. It grows from near sea level to moderate mountain elevations.

In its natural habitat, Cascara is often found along streamsides in mixed deciduous-coniferous forests, and in moist montane forests at moderate elevations. It is a common understory tree in Bigleaf Maple (Acer macrophyllum) forests, growing alongside Red-osier Dogwood (Cornus stolonifera) and Red Alder (Alnus rubra). The species is notably shade-tolerant, thriving beneath the canopy of taller conifers where many other trees struggle.

Historically, the high commercial demand for Cascara bark led to severe over-harvesting from wild populations throughout the 1900s, which significantly reduced Cascara’s abundance across much of its range. Conservation efforts and the decline of commercial bark harvesting (after the FDA banned cascara-based laxatives in 2002) have allowed some recovery, but the species remains less common than it once was in many areas.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Cascara: Western Oregon & Western Washington

Growing & Care Guide

Cascara is a resilient and adaptable native tree that is surprisingly easy to grow once you understand its preferences. In the wild, it thrives in the moist, shaded understory — and replicating those conditions in your garden will produce a healthy, attractive specimen.

Light

One of Cascara’s greatest strengths is its exceptional shade tolerance. It grows well in everything from full sun to deep shade, making it one of the most versatile native trees for challenging planting sites. In full sun, it develops a denser, more compact form; in shade, it grows taller and more open, reaching toward available light. This flexibility makes it ideal for understory plantings beneath taller conifers or as a standalone specimen.

Soil & Water

Cascara prefers moist, well-drained soil — the kind found naturally along streambanks and in valley bottoms. It thrives in loamy or sandy soils with a slightly acidic to neutral pH (5.5–7.0). While it needs consistent moisture and performs best in areas with regular rainfall, established trees can tolerate brief dry periods. Mulching with 2–3 inches of organic material (leaf litter, bark chips) helps retain soil moisture and mimics the natural forest floor conditions Cascara prefers.

Planting Tips

Plant Cascara in fall or early spring for best establishment. Choose a site with morning sun and afternoon shade for optimal growth, or tuck it beneath the canopy of larger trees. Space plants 10–15 feet apart if creating a naturalistic grove or screen. The tree transplants well from container stock — look for it at Pacific Northwest native plant nurseries.

Pruning & Maintenance

Cascara requires minimal pruning. Remove dead or crossing branches in late winter while the tree is dormant. If you prefer a more tree-like form over a multi-stemmed shrub, gradually remove lower branches to reveal the attractive splotchy bark. Avoid heavy pruning, as the species recovers slowly from major cuts. Cascara is naturally pest- and disease-resistant, making it a low-maintenance addition to the landscape.

Landscape Uses

Cascara’s versatility makes it valuable in many garden settings:

- Understory planting beneath tall conifers or deciduous shade trees

- Riparian restoration along streams, ponds, and wetland edges

- Wildlife gardens — the berries draw dozens of bird species

- Native hedgerow or screen when planted in groups

- Woodland gardens and naturalized forest-edge plantings

- Shade gardens — one of few native trees thriving in deep shade

- Erosion control on slopes and streambanks

Fire Ecology

Cascara is typically top-killed by fire but may resprout vigorously from the root crown. After more severe fires, it reestablishes from off-site seed beginning the second year after the fire, distributed by birds and mammals. In its natural range, Cascara typically inhabits areas with fire regimes on 30- to 150-year intervals, though it also occurs in old-growth forests with fire return intervals exceeding 500 years.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Cascara is one of the most ecologically valuable small trees in the Pacific Northwest, providing food, shelter, and habitat structure across multiple seasons.

For Birds

The dark purple-black berries are consumed by over 40 species of birds, including American Robins, Varied Thrushes, Cedar Waxwings, Band-tailed Pigeons, Steller’s Jays, and various finches and sparrows. The dense, brushy growth form provides excellent nesting habitat and thermal cover, while the tiny spring flowers attract the insects that many songbirds depend on during breeding season.

For Mammals

Bears — including Olympic Black Bears — are major consumers of Cascara fruit and foliage. Raccoons and Oregon Gray Foxes eat the berries, while Ring-tailed Cats consume them where ranges overlap in northern California. Mule Deer browse the foliage in Oregon, and Elk do the same in northern Idaho, particularly during winter when other browse is scarce. The dense stands Cascara creates provide abundant thermal cover and hiding places for a wide range of wildlife.

For Pollinators

Though small, Cascara’s spring flowers attract native bees, honeybees, and a variety of beneficial insects. The flowers bloom in the forest understory, providing nectar in a habitat layer where few other flowering plants are active at that time of year — making them especially valuable for early-season pollinators.

Ecosystem Role

Cascara plays a significant role in forest ecology. As a shade-tolerant understory species, it fills an important structural niche — creating a mid-canopy layer that increases habitat complexity. Its leaf litter decomposes faster than conifer needles, enriching the soil and supporting the mycorrhizal networks and invertebrate communities that underpin forest health. The seeds, distributed widely by birds and mammals, help Cascara colonize forest gaps and disturbed areas, contributing to forest succession and resilience.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Cascara holds one of the most remarkable ethnobotanical histories of any Pacific Northwest tree. Indigenous peoples — including the Quinault, Squaxin Island, and other Coast Salish nations — used the aged, dried bark as a laxative long before European contact. In the Chinook Jargon, a trade language of the Pacific Northwest, Cascara was known as “chittem bark” or “chitticum bark.”

Spanish colonizers named it cascara sagrada — “sacred bark” — and following its introduction to formal U.S. medicine in 1877, it became the most popular natural laxative in North America, replacing the berries of European buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica). For over a century, Cascara bark was a major commercial product in the Pacific Northwest. Bark collectors would strip trees in spring and early summer, when the bark peels most easily, then dry it in shade for several months — fresh bark causes violent vomiting and must be aged before use.

The bark trade devastated wild Cascara populations throughout the 1900s. In 2002, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration banned cascara-based over-the-counter laxatives due to safety concerns, effectively ending the commercial harvest. Today, Cascara continues to be sold as a dietary supplement, though its use carries significant health risks including dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and potential adverse interactions with prescription medications.

Beyond its medicinal history, Cascara wood has been used locally for fence posts, firewood, and small woodworking projects. The tree is also planted ornamentally and for erosion control, and Cascara honey — while reportedly tasty — is noted for being mildly laxative.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Cascara the same as Cascara Sagrada?

Yes. “Cascara Sagrada” (Spanish for “sacred bark”) is the name used in medicine and herbal products. The tree itself is most commonly called simply Cascara in the Pacific Northwest, while “chittem bark” or “chitticum” comes from the Chinook Jargon trade language.

Can you eat Cascara berries?

The berries can technically be eaten raw or cooked, but they have a strong laxative effect and a bitter taste. They are best left for the birds and wildlife that depend on them. The bark is also not safe to consume without proper aging and preparation.

How fast does Cascara grow?

Cascara has a moderate growth rate, typically adding 1–2 feet per year under favorable conditions. Growth is fastest in moist, partially shaded sites with rich soil. In deep shade, growth is slower but the tree remains healthy and long-lived.

Is Cascara endangered?

Cascara is not officially listed as endangered, but its populations were significantly reduced by commercial bark harvesting during the 1900s. Since the FDA banned cascara-based laxatives in 2002, harvesting pressure has decreased and populations are slowly recovering. Planting Cascara in your garden helps support this recovery.

Can Cascara grow in full sun?

Yes — despite being shade-tolerant, Cascara grows well in full sun as long as it has adequate moisture. In sunnier sites, it develops a denser, more compact form. Just ensure consistent watering during summer dry spells, especially in the first few years after planting.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Cascara?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: Oregon · Washington