Giant Sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum)

Sequoiadendron giganteum, commonly known as Giant Sequoia or Sierra Redwood, stands as one of Earth’s most magnificent and awe-inspiring trees. These ancient giants, found naturally only in the western Sierra Nevada of California, represent some of the largest living organisms on our planet by volume. With their massive trunks, towering heights reaching over 250 feet, and lifespans measured in millennia, Giant Sequoias embody the grandeur and resilience of California’s native forests.

Giant Sequoias are distinguished by their enormous size, distinctive reddish-brown fibrous bark that can be over 2 feet thick, and their remarkable fire resistance. The trees develop massive, buttressed trunks that can exceed 30 feet in diameter, while their crowns spread into broad, irregular shapes that create distinctive silhouettes against mountain skies. The small, scale-like leaves are arranged in spirals around the twigs, and the trees produce distinctive egg-shaped cones that require fire or hot, dry conditions to release their seeds.

These living monuments occur naturally in isolated groves scattered along the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada, typically at elevations between 4,000 and 8,000 feet. Giant Sequoias require specific conditions to thrive: deep, well-drained soils, adequate moisture, and periodic fire cycles that clear competing vegetation and create ideal seedbed conditions. Their natural rarity and specialized habitat requirements make them among California’s most precious natural treasures.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Sequoiadendron giganteum |

| Family | Cupressaceae (Cypress) |

| Plant Type | Evergreen Conifer |

| Trunk Diameter | 15–35 ft |

| Growth Rate | Fast when young, then moderate |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Soil Type | Deep, well-drained |

| Soil pH | 6.0–7.0 (slightly acidic to neutral) |

| Lifespan | 2,000–3,500+ years |

| Fire Resistance | Extremely high |

| Conservation Status | Endangered (limited range) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 6–8 |

Native Range

Giant Sequoia has perhaps the most restricted native range of any major tree species in North America, occurring naturally only in about 75 isolated groves scattered along the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada in California. This limited distribution spans roughly 260 miles from Placer County in the north to Tulare County in the south, at elevations typically between 4,000 and 8,000 feet.

The species’ range represents the remnant of once-extensive forests that covered much of western North America during the Miocene epoch, 5-20 million years ago. Climate changes, particularly increasing aridity and cooling temperatures, gradually reduced Giant Sequoia populations to their current refugial locations in the Sierra Nevada, where specific topographic and climatic conditions maintain the moisture and temperature regimes these trees require.

Within their limited range, Giant Sequoias occur in mixed coniferous forests alongside White Fir (Abies concolor), Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana), Ponderosa Pine (Pinus ponderosa), and Incense Cedar (Calocedrus decurrens). The trees require deep, well-drained soils, adequate summer moisture, and protection from extreme weather events that their massive size and shallow root systems make them vulnerable to.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Giant Sequoia: California Native Plants

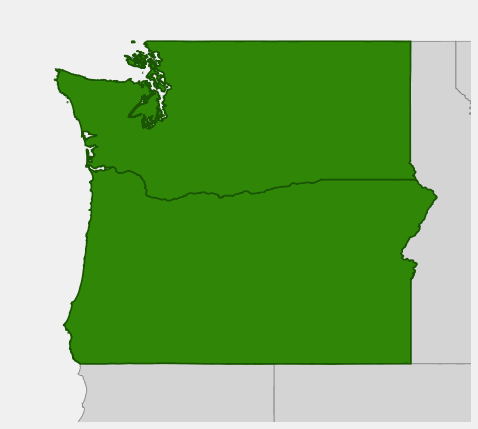

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Giant Sequoia: Western Oregon & Western Washington

Growing & Care Guide

While Giant Sequoia can be successfully grown outside its native range as an ornamental tree, cultivation requires understanding and replicating the specific conditions that allow these magnificent trees to thrive in their natural habitat.

Climate Requirements

Giant Sequoias require a climate with cool, wet winters and warm, dry summers, but with adequate soil moisture year-round. They are cold-hardy to USDA Zone 6 but struggle in areas with extreme heat, high humidity, or insufficient winter chill hours. The trees perform best in regions with Mediterranean or modified continental climates that provide winter temperatures below 45°F for several months.

Soil & Site Preparation

The most critical requirement is deep, well-drained soil — Giant Sequoias can develop root systems extending over 100 feet from the trunk and need unrestricted soil depth for proper anchorage and nutrient uptake. Ideal soils are sandy loams or loamy soils with excellent drainage and a pH between 6.0-7.0. Heavy clay soils or areas with high water tables are unsuitable, as waterlogged conditions quickly kill these trees.

Planting & Establishment

Plant container-grown specimens in early spring after the last frost. Choose a location with full sun exposure and protection from strong winds — despite their ultimate massive size, Giant Sequoias have relatively shallow root systems that make them vulnerable to windthrow. Space trees at least 30-50 feet from buildings and other structures to accommodate their eventual size. Young trees grow rapidly, potentially adding 2-3 feet in height annually under optimal conditions.

Watering & Irrigation

Consistent moisture is essential, especially during the establishment period and summer dry spells. Deep, infrequent watering encourages deep root development. Mature trees are somewhat drought-tolerant but perform best with supplemental irrigation during extended dry periods. Avoid frequent shallow watering, which encourages surface rooting and makes trees less resilient.

Pruning & Maintenance

Pruning should be minimal and limited to removing dead, damaged, or competing leader branches. Never top or heavily prune Giant Sequoias, as they do not respond well to major cuts and may develop structural problems. The trees naturally shed lower branches as they mature, a process called “self-pruning” that should not be interfered with unless branches pose safety hazards.

Landscape Uses

Giant Sequoias serve as magnificent specimen trees in large landscapes, parks, and estates where their eventual massive size can be accommodated. They work well as:

- Specimen trees in large open areas

- Memorial plantings — their longevity makes them living monuments

- Windbreaks in appropriate climates (though vulnerable when young)

- Educational plantings in botanical gardens and arboreta

- Long-term landscape investments — trees planted today will become heritage trees for future generations

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Despite their limited natural range, Giant Sequoias support a specialized community of wildlife adapted to these unique forest ecosystems. The massive trees create distinctive habitat conditions that support both common and rare species.

For Birds

Giant Sequoia groves provide critical nesting habitat for several specialized bird species. The Great Gray Owl, California’s largest owl, depends on large snags and cavity sites in old-growth sequoia forests. Pileated Woodpeckers excavate nest cavities in dead sequoia wood, creating nesting sites that are later used by other cavity-nesting species including Wood Ducks, Mergansers, and various small songbirds.

The complex canopy structure supports diverse songbird communities, including Hermit Warblers, Golden-crowned Kinglets, and Brown Creepers that forage on the massive bark surfaces. Red Crossbills and White-headed Woodpeckers feed on sequoia seeds, while Steller’s Jays cache the seeds and help with dispersal.

For Mammals

Black Bears utilize sequoia groves for denning sites, often creating dens in the hollow bases of large trees or in the root systems. The bears also feed on sequoia seeds when cones are abundant. Flying Squirrels nest in sequoia cavities and feed on the seeds, while chickarees (Douglas Squirrels) are important seed dispersers, caching sequoia seeds throughout the forest.

Deer and elk use sequoia groves for thermal cover, particularly during hot summer months when the massive tree canopies provide cool microclimates. Mountain Lions and Bobcats hunt in the understory where dense vegetation provides stalking cover.

For Unique Species

Giant Sequoia groves support several rare and endemic species found nowhere else. The Giant Sequoia Slender Salamander (Batrachoseps kawia) is found only in sequoia groves and depends on the moist, cool microclimates these forests provide. Various rare beetles and other invertebrates have evolved specifically to utilize giant sequoia bark, wood, and associated plant communities.

Ecosystem Engineering

The massive size and longevity of Giant Sequoias make them “ecosystem engineers” that profoundly modify their environment. Their enormous trunks create unique microclimates — the shaded, humid conditions around the base of large trees support different plant and animal communities than the surrounding forest. When giant sequoias eventually fall, they create “nurse logs” that can support entire ecosystems for centuries as they slowly decompose.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Giant Sequoias have held profound cultural significance for Indigenous peoples and continue to inspire awe and reverence in all who encounter them. The trees’ immense size and ancient age have made them symbols of natural permanence and spiritual power throughout human history in California.

Indigenous Relationships

The Mono, Yokuts, and other Indigenous peoples of the Sierra Nevada have lived alongside Giant Sequoias for thousands of years. These groups developed sophisticated fire management practices that maintained the open understory conditions sequoias require for regeneration. Traditional burning prevented the buildup of dense undergrowth that would compete with sequoia seedlings and create conditions for catastrophic wildfires.

Indigenous peoples used various parts of the trees for practical purposes, though the extremely thick, soft bark was generally not suitable for most construction purposes. However, the fibrous bark was sometimes used for bedding or insulation. More importantly, the groves themselves served as important ceremonial and spiritual sites, with the ancient trees recognized as living beings deserving of respect and protection.

European-American Discovery & Exploitation

The first documented encounter between European-Americans and Giant Sequoias occurred in 1833 when members of the Joseph Walker expedition encountered trees in what is now Yosemite National Park. However, these initial reports were dismissed as exaggerated until the 1850s when gold miners “rediscovered” the trees and began promoting them as tourist attractions.

Unfortunately, the early period following European-American discovery was marked by exploitation and destruction. Several of the largest and most magnificent trees were cut down in misguided attempts to create tourist attractions or to provide “proof” of their existence to skeptical Eastern audiences. The famous “Mark Twain Tree” was felled in 1891 specifically to create cross-sections for display, while other giants were cut down to clear land or for timber, despite the wood’s poor quality for construction.

Conservation Movement

Giant Sequoias played a pivotal role in the birth of the American conservation movement. The threat of continued logging and development of sequoia groves spurred early conservationists to action, leading to the establishment of Sequoia National Park in 1890 — making it the second national park in the United States, after Yellowstone.

John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, was particularly passionate about protecting Giant Sequoias, writing: “Any fool can destroy trees… It took more than three thousand years to make some of the trees in these Western woods—trees that are still standing in perfect strength and beauty, waving and singing in the mighty forests of the Sierra.”

Modern Cultural Significance

Today, Giant Sequoias continue to inspire visitors from around the world and serve as powerful symbols of conservation success. The trees appear on California’s state quarter and are featured in countless photographs, artworks, and nature documentaries. Many individual trees have been given names and are recognized as distinct personalities — General Sherman, General Grant, and President are among the most famous named sequoias.

The trees also serve important roles in environmental education, helping people understand concepts of deep time, ecosystem connectivity, and the importance of protecting old-growth forests. Their extreme longevity — some trees are over 3,500 years old — provides living connections to human history spanning from before the Bronze Age to the present.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the difference between Giant Sequoia and Coast Redwood?

Giant Sequoias are bulkier with massive, buttressed trunks and grow only in the Sierra Nevada mountains. Coast Redwoods are taller but more slender, with smaller cones, and grow in the fog belt near the Pacific coast. Coast Redwoods are the tallest trees, while Giant Sequoias are the largest by volume.

Can Giant Sequoias be grown outside of California?

Yes, but they require specific climate conditions: cool, wet winters and warm, dry summers with adequate soil moisture year-round. They’re successfully grown in parts of Oregon, Washington, the UK, and other regions with suitable Mediterranean or modified temperate climates.

How long do Giant Sequoias live?

Giant Sequoias can live over 3,500 years, making them among the longest-lived organisms on Earth. Many mature trees in protected groves are 2,000-3,000 years old, meaning they were already ancient when Europeans first arrived in North America.

Why don’t Giant Sequoias grow larger?

Despite their massive size, Giant Sequoias are limited by the same physical constraints as other trees — their ability to transport water and nutrients from roots to leaves. The tallest sequoias reach about 280 feet because beyond that height, the trees can’t efficiently pump water to their uppermost branches.

Are Giant Sequoias endangered?

While not officially listed as endangered, Giant Sequoias are considered vulnerable due to their extremely limited range and threats from climate change, drought, and increasingly severe wildfires. Climate change is pushing conditions outside the range these trees evolved to tolerate.

Identification

Giant Sequoia is unmistakable once you understand its key identifying characteristics. These ancient conifers develop distinctive features that set them apart from all other trees, even their close relatives like the Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides).

Size & Growth Form

Giant Sequoias are among the largest living organisms on Earth by volume, with mature trees reaching 200-280 feet tall and trunk diameters of 15-35 feet. The massive trunks develop a distinctive swollen, buttressed base that can be even wider than the main trunk, helping support the enormous weight above. Young trees have a classic conical Christmas tree shape, but mature specimens develop irregular, rounded crowns with massive horizontal branches.

Bark

The bark is one of the most distinctive features of Giant Sequoia. It’s thick (up to 2 feet), fibrous, and deeply furrowed with a rich reddish-brown to cinnamon color. The bark is remarkably soft and spongy to the touch, easily compressed with a finger, and can be pulled off in long, stringy strips. This thick, fire-resistant bark is key to the tree’s survival strategy, protecting the living tissue from even intense forest fires.

Leaves & Twigs

The leaves are small, scale-like, and arranged spirally around the twigs, overlapping like shingles. Individual leaves are 3-6mm long, blue-green to gray-green in color, and have sharp, pointed tips. The foliage has a distinctive texture, feeling somewhat prickly to the touch. Young twigs are green, becoming brown with age, and the overall branching pattern creates dense, layered foliage masses.

Cones & Seeds

Giant Sequoia produces distinctive egg-shaped cones that are 2-3 inches long and 1.5-2 inches wide. The cones are initially green, turning brown as they mature over 18-20 months. Each cone contains 200-400 tiny seeds that are only 3-6mm long with small wings. The cones can remain closed on the tree for up to 20 years, requiring heat from fire or hot, dry conditions to open and release seeds.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Giant Sequoia?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: Oregon · Washington