Chestnut Oak (Quercus prinus)

Quercus prinus, the Chestnut Oak, is a stately native deciduous tree of the eastern United States, renowned for the massive, deeply ridged and furrowed bark that makes it one of the most distinctive oaks in the region. Growing predominantly on rocky ridges, dry slopes, and sandy soils where many trees struggle to thrive, Chestnut Oak is the dominant tree of the Appalachian ridge-and-valley forests — a tough, resilient hardwood that has shaped the ecology, economy, and culture of the Mid-Atlantic region for centuries. Its large, distinctively lobed leaves recall those of the American Chestnut — giving rise to its common name — though it is a true oak, complete with large, sweet acorns that are among the most valuable wildlife foods produced by any eastern tree.

Mature Chestnut Oaks reach 60–70 feet in height with a broad, rounded crown. The tree is perhaps most famous for its extraordinary bark: massively thick, deeply channeled into dark, blocky ridges separated by lighter-colored furrows — among the most distinctive and photogenic bark of any North American tree. This thick bark, once extensively harvested for its high tannin content used in leather production, was so valuable that entire forests were clear-cut during the 18th and 19th centuries, earning Chestnut Oak the nickname “Tanbark Oak.” Today, this same magnificent bark is simply one of the great visual pleasures of winter walks through the eastern ridges and valleys.

For wildlife gardeners, naturalists, and restoration ecologists, Chestnut Oak is a keystone species. Its large, sweet acorns are eagerly consumed by white-tailed deer, black bears, Wild Turkeys, Blue Jays, and dozens of other species. As a host plant, it supports over 450 species of Lepidoptera caterpillars — making it one of the most ecologically productive native trees a homeowner can plant. Chestnut Oak thrives in challenging sites with thin, rocky, or sandy soils, making it a valuable tree for difficult terrain where other oaks may fail.

Identification

Chestnut Oak is a large deciduous tree, typically 60–70 feet tall with a trunk diameter of 2–4 feet and a broad, irregular crown. In the open it develops a full, rounded crown; on rocky ridges it often grows with a somewhat contorted, picturesque form. Old-growth specimens can exceed 100 feet. The tree’s overall structure — massive trunk with deeply furrowed bark, large spreading branches, and large hanging leaves — gives it a look of great age and permanence.

Bark

The bark of Chestnut Oak is among the most impressive of any eastern tree — massively thick (up to 1.5 inches), very dark grayish-black to dark brown, deeply and broadly ridged and furrowed into large, blocky plates. The furrows are lighter in color than the ridges, creating a striking contrast. The bark is high in tannins — historically the primary reason for the tree’s commercial exploitation — and its thickness is an adaptation to fire, which periodically sweeps the dry ridges where Chestnut Oak dominates.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and very large — typically 4–9 inches long and 2–4 inches wide. They are distinctive: oblong to obovate in shape, with large, rounded, wavy-margined lobes (typically 7–15 pairs of rounded teeth) that give the leaf a distinctly coarsely-toothed appearance rather than the deeply incised lobes of Red or Scarlet Oak. The leaf shape closely resembles that of American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) — hence the common name. Leaves are dark yellow-green above, paler and somewhat hairy below. In autumn they turn to warm yellow-brown, orange, or reddish-bronze tones.

Flowers & Acorns

Like all oaks, Chestnut Oak produces separate male and female flowers on the same tree. Male flowers hang in pendulous yellowish-green catkins 3–4 inches long in mid-spring. Female flowers are tiny, inconspicuous reddish structures appearing in leaf axils. The acorns that result are among the largest produced by any eastern oak — typically ¾ to 1.5 inches long, oval to oblong, with a distinctive deep, rough-scaled cup covering about half the acorn. The acorns are relatively sweet (low tannin) and highly palatable to wildlife, ripening in one growing season (a white oak group characteristic).

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Quercus prinus |

| Family | Fagaceae (Beech) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 60–70 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | April – May |

| Flower Color | Yellowish-green (catkins) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–8 |

Native Range

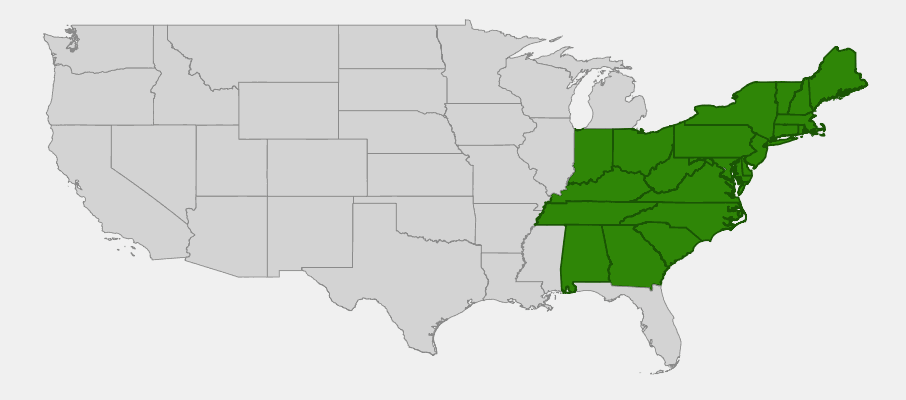

Chestnut Oak is native to the eastern United States, ranging from southwestern Maine south through New England, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, south along the Appalachian Mountains through Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Georgia, reaching into Alabama in the South. It is most abundant and ecologically dominant on the dry, rocky ridges and slopes of the Appalachian Mountains and Ridge-and-Valley Province, where it is often the most common tree species.

The species is particularly characteristic of the Appalachian Dry Oak Forest — a plant community defined by its presence on rocky, thin-soiled ridgetops and south-facing slopes where drought stress and periodic fire maintain an open oak woodland structure. In these habitats, Chestnut Oak grows with Pitch Pine (Pinus rigida), Black Oak (Quercus velutina), Scarlet Oak (Quercus coccinea), Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.), and Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia). It also occurs on dry, sandy soils of the coastal plain and piedmont, though it is less dominant there.

Chestnut Oak reaches its greatest abundance and dominance on the dry ridges of the central Appalachians — from central Pennsylvania through West Virginia and Virginia. Here it can constitute 50–80% of the forest canopy on exposed ridges, creating distinctive ridge-top woodlands with open understories of blueberries and huckleberries beneath the broad oak canopy. These forests are among the most distinctive and ecologically important plant communities of the Mid-Atlantic region.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Chestnut Oak: New York, Pennsylvania & New Jersey

Growing & Care Guide

Chestnut Oak is an excellent landscape tree for challenging sites — particularly dry, rocky, or sandy soils where other oaks struggle. It is slow to establish but becomes an exceptionally long-lived, low-maintenance tree that will outlast generations of homeowners. Understanding its preference for excellent drainage and avoiding soil disturbance are the keys to success.

Light

Chestnut Oak grows best in full sun to partial shade. Young seedlings are somewhat shade tolerant, allowing them to establish beneath a canopy, but mature trees develop their best form and produce the most acorns in full sun. In the landscape, choose a site with at least 4–6 hours of direct sun for optimal performance. The tree naturally occurs on open, sun-exposed ridges and slopes — mimic these conditions when possible.

Soil & Water

Chestnut Oak is uniquely well-adapted to dry, nutrient-poor, rocky or sandy soils with excellent drainage — conditions that would stress most large trees. It does NOT thrive in wet, clay, or poorly drained soils. Once established, it is highly drought tolerant and requires no irrigation. Avoid compacting the soil around the root zone, which extends far beyond the canopy dripline. Chestnut Oak resists soil compaction less well than some other oaks and should not be planted in areas with heavy foot traffic or construction disturbance.

Planting Tips

Plant in fall or early spring as a small container-grown or balled-and-burlapped specimen. Chestnut Oak transplants best when young — large specimens are difficult to establish. Dig a wide, shallow planting hole (no deeper than the root ball, 2–3× wider). Mulch with 3–4 inches of organic matter, keeping mulch away from the trunk. Water regularly the first two years until established. After that, supplemental irrigation is rarely needed.

Pruning & Maintenance

Chestnut Oak requires minimal pruning. Remove dead, diseased, or crossing branches in late winter when the tree is dormant. Avoid heavy pruning, which can stress the tree and create large wounds. The species is generally quite resistant to oak wilt, unlike Red and Black Oaks, though it should still not be pruned during spring when oak wilt vectors are most active. Otherwise, Chestnut Oak is a remarkably self-sufficient tree with few serious pest or disease problems.

Landscape Uses

- Shade tree for large properties with dry, well-drained soils

- Ridgeline and slope planting — excels where drainage is sharp

- Wildlife garden anchor — supports hundreds of caterpillar species and provides acorns

- Naturalistic woodlands and Appalachian-style restoration plantings

- Timber and lumber — excellent quality hardwood for furniture, flooring, and construction

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Chestnut Oak is one of the most ecologically valuable native trees in the eastern United States. It is simultaneously a cornerstone of the forest structure on dry Appalachian ridges and a critical wildlife food plant, supporting an exceptional diversity of birds, mammals, and insects.

For Birds

The large, relatively sweet acorns of Chestnut Oak are consumed by Wild Turkeys, Wood Ducks, Blue Jays, Red-headed Woodpeckers, and numerous other birds. Blue Jays, in particular, are important acorn dispersers — caching and transporting acorns far from parent trees, effectively planting new oaks across the landscape. The tree’s dense canopy, complex bark texture, and large size provide nesting sites for large birds including Barred Owls and Red-tailed Hawks, while the caterpillar-rich foliage supports warbler and vireo populations during breeding season.

For Mammals

White-tailed deer, black bears, raccoons, squirrels, and chipmunks all feed heavily on Chestnut Oak acorns, which are preferred by many mammals due to their relatively low tannin content and large size. Gray Squirrels cache enormous quantities of acorns, contributing to oak regeneration across the forest. Black bears travel significant distances to reach productive Chestnut Oak groves during the pre-denning hyperphagia period in autumn.

For Pollinators

Like all oaks, Chestnut Oak is wind-pollinated and not a significant nectar source for bees. However, its abundant spring catkins provide early pollen for pollen-collecting native bees and other insects. More importantly, oaks are among the most important host plants for Lepidoptera caterpillars in eastern North America — Chestnut Oak supports over 450 moth and butterfly caterpillar species, whose protein-rich bodies are essential food for nesting birds raising young.

Ecosystem Role

As the dominant tree on millions of acres of Appalachian ridgeline, Chestnut Oak is an ecological foundation species — its presence defines the structure, species composition, and dynamics of dry oak forest ecosystems. Its acorn crop drives boom-and-bust cycles that affect populations of deer, bears, mice, and the hawks, owls, and other predators that feed on them. Chestnut Oak is irreplaceable in the ecology of the Appalachian highlands.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Chestnut Oak has been intensively used by both Indigenous peoples and European colonizers throughout its range. The most historically significant use was the bark, which contains exceptionally high concentrations of tannins — the compounds used to convert animal hides into leather. Chestnut Oak bark was the primary tanning material used throughout the eastern United States and was harvested so extensively during the 18th and 19th centuries that it fundamentally altered forest composition across vast areas of Pennsylvania, New York, and the southern Appalachians. Tanneries were a cornerstone of frontier economics, and “tanbark” operations stripped hillsides of Chestnut Oak, leaving the wood to rot, as only the bark had commercial value at the time.

Beyond tanning, Chestnut Oak wood was prized for lumber — its grain is coarser than White Oak but the wood is nearly as strong and durable, making it excellent for railroad ties, fence posts, flooring, and furniture. Indigenous peoples, including the Cherokee, Delaware, and Iroquois, used various parts of the tree medicinally: bark decoctions were applied to treat sore throats, skin conditions, and as an astringent. The relatively sweet acorns were ground into flour and used as a food starch after leaching away the remaining tannins in running water.

Today, Chestnut Oak is valued primarily as a wildlife tree, shade tree, and timber species. The high tannin content that made the bark so commercially valuable historically is now an interesting botanical curiosity rather than an economic driver. As forest ecologists have come to understand the critical importance of oak diversity for wildlife and ecosystem health, Chestnut Oak has gained new appreciation as an ecologically essential native tree that deserves a prominent place in any landscape restoration effort within its native range.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Chestnut Oak the same as White Oak?

No — Chestnut Oak (Quercus prinus) and White Oak (Q. alba) are distinct species, though both belong to the White Oak group (acorns mature in one year, lower tannin content). They can sometimes grow together but occupy different ecological niches: White Oak prefers richer, moister upland soils, while Chestnut Oak dominates drier, rockier, more acidic ridge sites.

Why is it called Chestnut Oak?

The name comes from the resemblance of its large, coarsely-lobed leaves to those of the American Chestnut (Castanea dentata). Both species have large, elongated leaves with rounded, wavy-margined teeth. They are not botanically related, but grow together on Appalachian ridges where the leaf shape comparison is striking.

How long does Chestnut Oak live?

Chestnut Oak is a long-lived tree — exceptional specimens can exceed 400 years. In managed landscapes, well-sited trees regularly reach 200–300 years. This longevity makes it a true investment in natural heritage when planted on appropriate sites.

When do Chestnut Oaks produce acorns?

Chestnut Oak begins producing acorns at about 20–25 years of age. Acorns ripen and fall in September–October. Like all oaks, Chestnut Oak produces heavy mast crops every 2–5 years, with lighter crops in intervening years — a strategy that periodically overwhelms seed predators to allow successful seedling establishment.

Does Chestnut Oak do well in urban conditions?

Chestnut Oak is less tolerant of urban stresses (soil compaction, pollution, poor drainage) than some other oaks. It performs best on dry, well-drained sites with minimal soil disturbance. It is not a good choice for street tree plantings or sites with heavy foot traffic. For urban planting, Swamp White Oak or Bur Oak are more adaptable. In suburban settings with suitable dry, rocky soil, Chestnut Oak can thrive magnificently.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Chestnut Oak?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: New York · Pennsylvania