False Indigo (Baptisia australis)

Baptisia australis, commonly known as False Indigo or Blue Wild Indigo, is one of the most striking and long-lived native perennials in the eastern United States. A member of the pea family (Fabaceae), it produces magnificent upright spikes of deep blue-violet, pea-shaped flowers in May and June — a color that is relatively rare among native spring wildflowers and makes it an immediate garden showstopper. The flowers give way to inflated, pea-pod-like seed capsules that dry to a charcoal gray-black and rattle in the wind, providing additional ornamental interest well into fall and winter.

What makes False Indigo especially valuable is its extraordinary longevity and low maintenance. Once established — which takes 2–3 years — a Baptisia plant lives for decades, gradually expanding into an impressive, shrub-like mound of blue-green, three-parted leaves. The root system runs deep, making the plant extremely drought tolerant and impossible to transplant once established. A 20-year-old specimen can be 4 feet tall and 5 feet wide, covered in hundreds of flower spikes in spring. It is genuinely a plant that improves with age and requires virtually no care once it has settled in.

False Indigo is also a nitrogen-fixer, hosting Rhizobium bacteria in root nodules that convert atmospheric nitrogen into forms available to soil organisms and neighboring plants — a significant ecological benefit in the garden. For native gardens in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, Baptisia is an anchor plant: dependable, deer resistant, drought tolerant, pollinator-rich, and spectacular in bloom.

Identification

False Indigo is a robust, clump-forming perennial reaching 3 to 6 feet tall in full bloom and 3 to 4 feet wide at maturity. The plant emerges early in spring as distinctive gray-green shoots that expand rapidly into a mound of blue-green, three-lobed compound leaves. The leaves are alternate, each composed of three oval leaflets about 1 to 2 inches long, with a smooth texture and a distinctive blue-green, slightly glaucous color. Stipules are persistent and leaf-like. The entire plant has a somewhat shrubby appearance and structure during the growing season.

Flowers & Fruit

The flowers are produced on upright racemes 6 to 12 inches long, with individual blossoms that are typical of the pea family: a large upper “banner” petal, two “wing” petals, and a keel. Each flower is ¾ to 1 inch long, deep blue-violet to indigo in color, and very attractive. Bloom occurs from late May through June, lasting 3–4 weeks, and the flower spikes are produced abundantly at the tips of the arching stems. After flowering, the seed pods develop and inflate dramatically, turning from green to black as they dry. These inflated pods, 1 to 2 inches long, persist through fall and winter, rattling with the loose seeds inside — earning Baptisia the folk name “Rattlebox.”

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Baptisia australis |

| Family | Fabaceae (Pea / Legume) |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous Perennial |

| Mature Height | 3–6 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate |

| Bloom Time | May – June |

| Flower Color | Deep blue-violet (indigo) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

Native Range

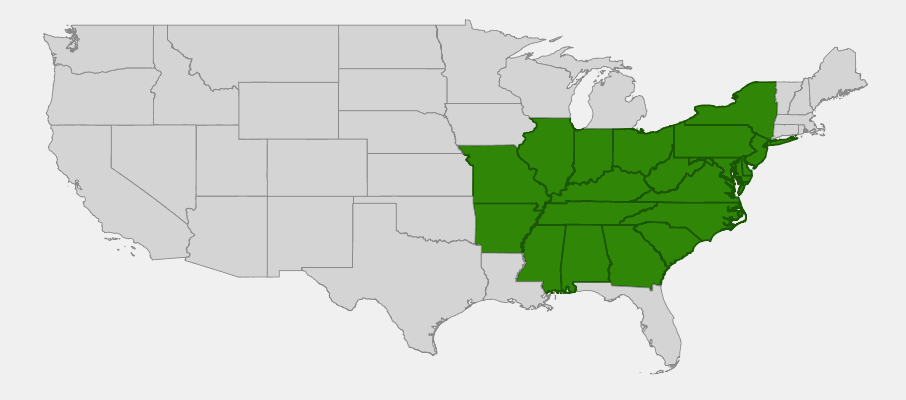

False Indigo is native to much of the eastern and central United States, with its natural range extending from Pennsylvania and New Jersey south through the Appalachian region to Georgia and Alabama, and west through the central states to Nebraska and Kansas. It grows naturally in open woods, meadows, prairies, stream banks, and woodland edges — characteristically in full sun to light shade with well-drained, somewhat acidic soils. In the wild, Baptisia is a species of disturbed and open habitats, historically maintained by fire and grazing.

In the Mid-Atlantic and northeastern states — including New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania — Baptisia occurs naturally along river banks and woodland edges in full sun, often in sandy or rocky soils where competition from taller vegetation is limited. It is a component of oak-hickory savannas and open floodplain forests in its more southerly and westerly range. The deep taproot system allows it to survive in well-drained, droughty soils where shallower-rooted competitors struggle.

The genus Baptisia contains numerous species native to the southeastern United States, several of which hybridize naturally in areas where their ranges overlap. Baptisia australis is the hardiest and most widely adapted species, and it is the most commonly cultivated in northern gardens. Recent hybridization work by plant breeders has produced a range of new colors including yellow, white, and bicolor forms, though the straight species blue-violet remains one of the most beautiful native perennials for the northeastern garden.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring False Indigo: New York, Pennsylvania & New Jersey

Growing & Care Guide

False Indigo is one of the most rewarding long-term investments in a native plant garden. The first year, it establishes its deep taproot and grows slowly; the second year it begins to show its potential; and by the third year it hits its stride as a spectacular, virtually maintenance-free perennial that improves with every passing decade.

Light

Full sun is strongly preferred for False Indigo. In full sun, the plant develops the densest, most compact form, with the most prolific flowering and the strongest stems. It will grow in part shade (3–5 hours direct sun) but becomes lankier and more open, producing fewer flower spikes and weaker stems that may require support. In deep shade, Baptisia rarely flowers and declines over time. For the most spectacular display, choose the sunniest available site.

Soil & Water

Baptisia prefers well-drained, average to lean soils with slightly acidic pH (5.5–7.0). It is remarkably drought tolerant once its deep taproot is established — typically after 2–3 years. Avoid rich, fertile soils that produce excessive, floppy vegetative growth. Also avoid poorly drained clay soils where water stands after rain, as the roots are susceptible to rot in saturated conditions. Sandy or rocky soils with good drainage are ideal. Once established, supplemental watering is rarely needed in the northeastern states.

Planting Tips

Plant False Indigo in spring or fall. Use container-grown plants — bare-root transplants are rarely available and the deep taproot makes established plants impossible to transplant without severe setback. Space plants 3–4 feet apart to allow for mature spread. Choose your location carefully, as mature plants are deeply rooted and very difficult to relocate. Baptisia is slow to establish in the first 1–2 years and may not flower well initially — patience is essential. Once established, the plant is virtually permanent and requires no division or replanting for decades.

Pruning & Maintenance

False Indigo requires almost no maintenance. The attractive seed pods can be left standing through fall and winter for ornamental value and bird habitat, then cut to the ground in late winter before new growth emerges. Baptisia does not need to be divided — in fact, division is very difficult due to the deep taproot and is not recommended unless absolutely necessary. The plant is resistant to deer, rabbits, most insects, and fungal diseases. It may develop powdery mildew in humid conditions in late summer, but this typically does not affect plant health or next year’s performance.

Landscape Uses

- Specimen focal point — dramatic blue flower spikes are a garden centerpiece in May–June

- Prairie or meadow garden — a signature plant in naturalistic plantings

- Back or mid-border perennial — shrubby mound provides structure throughout the season

- Nitrogen-fixing soil improver — benefits neighboring plants through nitrogen fixation

- Dry, challenging sites — thrives where other plants struggle with drought or lean soil

- Deer-resistant planting — reliable performer in high-deer-pressure areas

Wildlife & Ecological Value

False Indigo supports a specialized and ecologically important community of insects, particularly native bees and the caterpillars of several butterfly and moth species.

For Birds

The inflated seed pods of Baptisia are consumed by birds, particularly game birds, and the dried seed capsules that rattle in wind attract birds searching for food in fall and winter. The insect diversity supported by Baptisia’s flowers — including specialist bees, beetles, and caterpillars — provides important food resources for nesting and migrating birds throughout the season.

For Mammals

False Indigo is not a significant mammal food source, which is part of its value in high-deer-pressure landscapes. White-tailed deer generally avoid it due to alkaloids in the foliage that make it unpalatable. Small mammals occasionally consume the seeds from fallen pods. The deep taproot system helps stabilize slopes and streambanks, reducing erosion that can degrade mammal habitat.

For Pollinators

Baptisia is an exceptional native bee plant, particularly for large-bodied bees that can access the nectaries hidden within the pea-type flowers. Bumblebees are the primary pollinators — they “buzz pollinate” the flowers in a process that releases pollen through high-frequency vibration of the anthers. Eastern Bumblebee (Bombus impatiens), Brown-belted Bumblebee (B. griseocollis), and other bumblebee species are regular visitors. Wild Indigo Duskywing (Erynnis baptisiae) is a specialist butterfly whose caterpillars feed exclusively on Baptisia species — planting False Indigo directly supports this declining native butterfly. The caterpillars of Hoary Edge skipper, Wild Indigo skipper, and several moth species also rely on Baptisia as a host plant.

Ecosystem Role

As a legume, False Indigo forms nitrogen-fixing symbioses with Rhizobium bacteria in root nodules, converting atmospheric nitrogen into biologically available forms. This enriches the surrounding soil and benefits neighboring plants — an ecological service analogous to a natural fertilizer application. In prairie and meadow communities, Baptisia plays an important structural role, its deep roots accessing water and nutrients unavailable to shallower-rooted neighbors, while its above-ground biomass decomposes to feed soil organisms. The specialized relationships between Baptisia and its insect herbivores, particularly the duskywing butterfly, represent a co-evolutionary history stretching back millions of years.

Cultural & Historical Uses

The genus name Baptisia comes from the Greek bapto, meaning “to dip” — a reference to the use of some species as a dye plant. Indigenous peoples of the eastern United States used various Baptisia species for fiber dyeing, producing a blue dye that was used as a substitute for true indigo (Indigofera tinctoria), hence the common name “False Indigo.” The dye was less colorfast than true indigo but was readily available in the wild and was used by both Indigenous peoples and European settlers for coloring cloth, yarn, and baskets.

Medicinally, False Indigo was used by several Indigenous nations, including the Cherokee, who prepared root decoctions to treat various ailments. The roots were used as a purgative, to induce vomiting, and as a treatment for toothache and infections. The plant contains various alkaloids including baptifoline, cytisine, and anagyrine, which are toxic in large doses. The Cherokee also used the plant ceremonially, and various preparations were used in veterinary medicine to treat livestock diseases.

In the 19th century, Baptisia was included in various pharmacopeias and was used by Eclectic physicians — a 19th-century American medical movement that emphasized botanical treatments — as a treatment for typhoid fever and other infectious diseases. Modern research has investigated Baptisia extracts for immunostimulant properties, and commercial preparations are available in European herbal medicine. Despite this history, the plant’s medicinal use is not recommended without professional guidance due to potential toxicity. Today, Baptisia is grown almost exclusively as an ornamental and ecological garden plant, where its beauty, longevity, and wildlife value far exceed any medicinal application.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is my False Indigo not blooming?

Young Baptisia plants typically take 2–3 years to establish before blooming reliably. If your plant is established (3+ years old) and still not blooming, the most common causes are insufficient sun (needs at least 6 hours of direct sun) and overly rich soil that promotes vegetative growth at the expense of flowers. Move to a sunnier location or avoid fertilizing.

Can I move an established False Indigo?

This is not recommended. False Indigo develops an extremely deep, fragile taproot that makes transplanting established plants very difficult without killing them. Choose your planting location carefully when the plant is young. If you must divide or move it, do so in early spring with as large a root ball as possible, and accept that it will set back significantly.

Is False Indigo toxic?

Yes — the foliage, seeds, and roots contain alkaloids that are toxic if consumed in quantity. This is why deer avoid it. Keep away from children and pets, and wash hands after handling. The plant is safe to grow in the garden and is not a contact irritant.

What are those inflated black pods?

The pods are the seed capsules, which develop after flowering. They inflate dramatically as the seeds mature, turning from green to charcoal black by late summer. The seeds inside become loose and rattle when the pod is shaken, earning Baptisia the folk name “Rattlebox.” The pods add ornamental value through fall and winter and can be used in dried arrangements.

Does False Indigo spread aggressively?

No. False Indigo is a well-behaved garden plant that spreads slowly by expanding its clump over many years. It does self-sow, but seedlings are easy to remove when small. The deep taproot also means it doesn’t spread by root runners. An established plant simply gets larger and more impressive over the decades — not weedy.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries False Indigo?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: New York · Pennsylvania